Bahrain: U.S. Posture On The Uprising – Analysis

By CRS

By Kenneth Katzman

The U.S. response to the unrest in Bahrain has been, to some extent, colored by the response to the broader Middle East unrest, although with an eye toward the vital U.S. interests in Bahrain.

The U.S. concern is that a fall of the Al Khalifa regime and ascension of a Shiite-led government could increase Iran’s influence and lead to a loss of the use of Bahrain’s military facilities. In phone calls to their counterparts after the February 17, 2011, clearing of Pearl Roundabout, Secretary of State Clinton and Secretary of Defense Gates reportedly expressed concern to the Bahrain government for using force against the protesters.

White House spokesman Jay Carney said the violence was not an appropriate response to peaceful demonstrators making “reasonable demands.”

These contacts and statements apparently contributed to the earlier government decision to exercise restraint against protesters.

Some have criticized the Administration for previously muting criticism of Bahrain’s human rights record, citing Secretary of State Clinton’s comments in Bahrain on December 3, 2010, referring to the October 2010 elections, saying: “I am impressed by the commitment that the government has to the democratic path that Bahrain is walking on. It takes time; we know that from our own experience.”5

Just prior to the March 15, 2011, crackdown, Secretary of State Clinton and other U.S. officials had praised the release of political prisoners and called on all parties to take up the offer by the Crown Prince for a broad political dialogue on reform.6 In a statement, President Obama praised the February 26 cabinet reshuffle and King Hamad’s restatements of his commitment to reform.7

The U.S. position—in particular not calling for the Al Khalifa monarchy to come to an end—may reflect concern among U.S. officials about the consequences were the regime to fall.

U.S. officials fear that if a Shiite-led regime come to power there, Iran’s influence in Bahrain would increase to the point where it might be successful in persuading Bahrain to ask the United States to vacate Bahraini military facilities.

The U.S. position did not change significantly following the March 14, 2011, GCC intervention and subsequent crackdown. On March 19, 2011, Secretary Clinton reiterated the U.S. support for the Crown Prince’s offer of dialogue, and said

…Bahrain obviously has the sovereign right to invited GCC forces into its territory under its defense and security agreements.” She added, however, that “[The United States has] made clear that security alone cannot resolve the challenges facing Bahrain. As I said earlier this week, violence is not and cannot be the answer. A political process is. We have raised our concerns about the current measures directly with Bahraini officials and will continue to do so.

The Administration also stepped up efforts to help resolve the crisis. Assistant Secretary of State for the Near East, Jeffrey Feltman, was sent to Bahrain as of March 14, 2011, to attempt to achieve the beginning of a sustained dialogue between the government and the opposition.

The Obama Administration, which presented its FY2012 budget request on February 14, 2011, just as the unrest in Bahrain was growing, has not announced any alteration of its military and anti-terrorism assistance or arms sales policy for Bahrain.

In his February 25, 2011, visit, Joint Chiefs Chairman Mullen reaffirmed the U.S.-Bahrain defense relationship. However, press reports say arms sales to Bahrain and other U.S. allies are under review because of the unrest in the region.8

It is possible that outside experts and some in Congress might object to further sales to Bahrain, particularly of equipment that could be used against protesters.

The Saudi/GCC Intervention

With no dialogue under way, protests escalated through early March. On March 1, 2011, demonstrators blocked the entrance to the parliament building and delayed the meeting of its bodies for six hours. The protest also began to spark Sunni-Shiite clashes; some experts believed these had the potential to evolve into outright sectarian conflict.

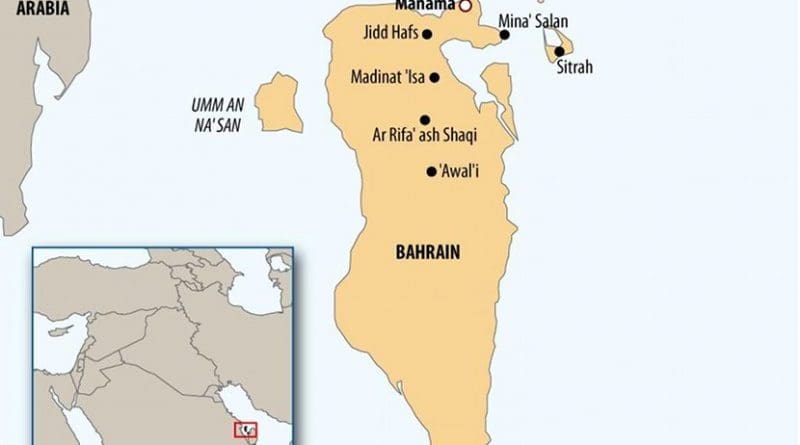

On March 13, 2011, protesters blockaded the financial district of the capital, Manama, prompting governmental fears that the unrest could choke this major economic sector. Security forces trying to contain the growing protests were overwhelmed and, on March 13, Bahrain requested that the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC), of which it is a member, send additional security forces to protect key sites. In response to the request, on March 14, 2011, a GCC force spearheaded by about 1,000 Saudi forces (in armored vehicles) and 500 UAE policemen crossed into Bahrain and took up positions at key locations in and around Manama.

Subsequently, on March 15, 2011, King Hamad declared a three-month state of emergency, and Bahraini security forces, backed by the GCC forces, cleared demonstrators from Pearl Roundabout (and demolished the pearl monument itself on March 19, 2011). Some additional protester deaths were reported in this renewed crackdown. In conjunction with the crackdown, seven Shiite leaders were arrested, including Al Haq’s Mushaima. Wefaq’s leader, Shaykh Ali Salman, was not arrested. The remaining Shiite ministers in the cabinet, many of the Shiites in the Shura Council, and many Shiites in other senior posts in the judiciary and elsewhere, resigned.

Well before intervening in Bahrain, the GCC states had begun to fear that the Bahrain unrest could spread to other GCC states. It was also feared that Iran might be able to exploit the situation. None of the other GCC states has a Shiite majority (like Bahrain), but most of them, including Saudi Arabia, have substantial Shiite minorities. The GCC states met at the foreign minister level on February 16, 2011, and expressed solidarity with the government of Bahrain.

King Hamad visited Saudi Arabia on February 23, 2011, for consultations on how to handle the unrest, and Crown Prince Salman visited UAE on March 2, 2011. Those countries have arranged for large pledges of aid to help the Bahrain government (and that of Oman, which also has faced unrest) create jobs for Shiites.

Some experts speculate that Saudi intervention could prompt a wider conflict; Al Haq leader Hassan Mushaima affirmed those fears in March 2011 when he warned that Saudi intervention could prompt Iranian intervention on the side of the Shiite protesters.

To date, there has been little evidence of direct Iranian intervention. However, Iranian leaders have criticized the Bahraini crackdown and Bahrain and Iran have withdrawn their ambassadors from each others’ capitals. On March 21, 2011, King Hamad indirectly accused Iran of involvement in the unrest by saying a “foreign plot” had been foiled by the GCC assistance.

Secretary of Defense Gates has not accused Iran of instigating the unrest but has warned that the protraction of the crisis allows Tehran opportunities to exploit it, perhaps by urging Bahrain’s Shiites not to compromise but instead seek outright replacement of the regime.9

Possible Outcomes

Outcomes are difficult to predict. Some believe the GCC intervention and subsequent crackdown has hardened the protest movement to the point where it will attempt to defy the government and drive it from power.

The overthrow of the government and the ascension of a Shiite-led regime is possible, although the GCC intervention has probably made this outcome less likely.

The Obama Administration and many experts believe that compromise is still likely, even in light of the GCC intervention. Ideas for a compromise include a change of the constitution to allow for direct selection of the prime minister by an empowered COR.

Some believe that, short of an alteration of the constitution, another potential compromise could involve Wefaq leader Shaykh Ali Salman becoming prime minister, although hardline Al Khalifa members are almost certain to oppose the ousting of Prime Minister Khalifa Al Khalifa. Another possibility could include the broad reshuffling of the cabinet to give Shiites many more ministerial posts and control of key economic ministries.

Other potential amendments to the constitution could include expanding the elected COR, enhancing its powers relative to the upper house, or abolishing the upper house. Other reforms could include redistricting that would permit Shiites to win a COR majority.

Author

Kenneth Katzman

Specialist in Middle Eastern Affairs

Source:

This article is a selected, edited section from the much longer March 21, 2011 Congressional Research Service report, Bahrain: Reform, Security, and U.S. Policy (PDF)

Notes:

5 Department of State. “Remarks With Foreign Minister Al Khalifa After Their Meeting.” December 3, 2010.

6 Secretary of State Clinton Comments on the Situation in the Middle East. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GbucMZUg3Gc

7 “Obama Welcomes Bahrain Cabinet Reshuffle.” Reuters, February 27, 2011.

8 Adam Entous. “U.S. Reviews Arms Sales Amid Turmoil.” Wall Street Journal, February 23, 2011.

9 http://www.stripes.com/gates-protracted-bahrain-negotiations-allowing-greater-iran-influence-1.137532

Firstly why must US have the fifth fleet base at Bahrain,unless she intends to attack Iran and separate Sistan province to eventually join

it to Baluchistan Province of Pakistan,next to

create Republic of Baluchistan with the intend

to deprive China and Russia of Gawadar port.

Secondly who is US to decide on the new type of

government in Bahrain, unless she wants to turn

the state into her colony.