The Welcome Return Of Interventionism – OpEd

By Peter John Cannon

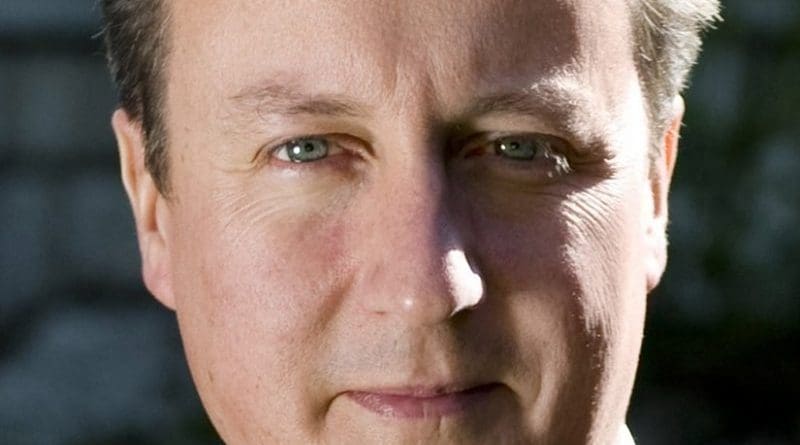

At the beginning of the year, few would have predicted that Britain and the United States would be involved in another military intervention. Britain, the United States and European nations were – and still are- cutting their defence budgets. Discussions on Afghanistan centred around dates for withdrawal, regardless of the result. In Britain, Prime Minister David Cameron poured scorn on the idea of liberal interventionism, saying: “We cannot impose democracy at the barrel of a gun.”i He later reiterated: “I am not a naïve neoconservative who thinks you can drop democracy out of an aeroplane at 40,000 feet.”ii Intervention and ‘hard power’ seemed to have fallen out of fashion. The US administration also now turned to dialogue and engagement.

Yet the wave of protest in the Middle East has shattered this cosy, complacent mindset. The pro-democracy demonstrations, and the repression they faced from numerous autocratic governments, forced Western governments to take sides. With a potential new wave of democratisation, Western leaders did not want to be on the wrong side of history. The violence unleashed by Colonel Gaddafi against his own people, on the doorstep of Europe and in full view of the world, forced Western leaders to decide: would they intervene, or would they stand aside and rely solely on diplomacy? In the face of such an imminent slaughter, with appeals for help from the Libyan opposition themselves and the neighbouring countries of the Arab League, non-intervention and ‘soft power’ become much more difficult to maintain. The leaders made the right choice.

The NATO operation in Libya has proved that Britain, France, the United States and other powers are still willing and able to intervene overseas in defence of human rights and to prevent further atrocities being committed by a murderous tyrant against his own people. The allies have been absolutely right to intervene to prevent a massacre in Benghazi, and to prevent Gaddafi from crushing all internal opposition. A failure to act would have sent a chilling message across the Middle East and Africa that dictators who showed the most brutality in crushing their own people could keep their grip on absolute power.iii

The United Nations is also, finally, fulfilling its responsibilities. This is the first military action taken under the UN doctrine of the Responsibility to Protect, adopted in 2006, which permits international intervention in a sovereign state to prevent a humanitarian disaster.iv The president of Rwanda, Paul Kagame, made a powerful point when he wrote: “No country knows better than my own the costs of the international community failing to intervene to prevent a state killing its own people… It is encouraging that members of the international community appear to have learnt the lessons of that failure… Rwanda can only stand in support.” v

Political consensus for intervention

What has been remarkable is not just that Western leaders have been willing to intervene militarily, and not just the degree of international consensus that was achieved in the UN Security Council, but the degree of political consensus that has been established within Britain and other European countries. In Britain, the opposition has given its full support to the Government in its actions. MPs voted by 559 to 15 in favour of the military action to enforce UN Security Council Resolution 1973. vi Even before the UN resolution, long-standing opponents of the Iraq war such as Menzies Campbell and Philippe Sands were calling for intervention in Libya and urging the Government to act.vii

Much has been made of the differences between the interventions in Iraq and Libya. While there are numerous significant differences, it is important not to overstate them for the sake of presenting one intervention as being ‘superior’ to the other. Without the removal of Saddam Hussein from power in Iraq, the democratic revolutions in the Middle East may never have happened. It would certainly be more difficult for democracy to take root in a region where there was still an oil-rich and heavily-armed Baathist Iraq, particularly given Saddam Hussein’s record of intervening in neighbouring countries. Rather than having Saddam Hussein trying to crush any democratic movement in the region, we instead witnessed Hoshyar Zebari, the foreign minister of Iraq and new head of the Arab League, calling for strong action against the regime of Colonel Gaddafi.viii

If Saddam Hussein had still been in power, and an uprising had broken out in Iraq, who could doubt that he would have responded every bit as brutally – or even more so – than Gaddafi? We saw him do it in 1991, after the first Gulf War. With regard to moral imperatives to intervene, Saddam Hussein slaughtered many more of his own people than Gaddafi. Although without the intervention in Iraq, Gaddafi would never have given up his weapons programmes, and so might now have a much greater capacity to wreak devastation on his own population and against any country which tried to intervene. The intervention in Libya should not be seen as something which proves that the ‘lessons of Iraq’ (as a mistaken intervention) have or have not been learnt, but rather as an event which shows that the ‘lessons of Iraq’ (as an example always used against every potential intervention) were false.

The British tradition of interventionism

One major difference is that whereas the United States took the lead over Iraq, in Libya the lead role has been taken by Britain and France. The Obama administration, by contrast, was cautious and uncertain in its approach, before finally giving its full support to military action. This was something few would have predicted. This should also provide the British Government and others with a lesson: we cannot always assume that the Americans will deal with every problem, and always rely on the United States to take the lead. In other words, we cannot assume that even if we do nothing, the United States will sort it out.

In his early calls for military action, David Cameron was following in a long and noble tradition within British foreign policy of liberal interventionism. This tradition can be traced back to the days of Canning, who supported the independence of Latin American states from Spain, and Palmerston, who backed constitutionalists against monarchists in Spain and Portugal in the 19th century.ix Today’s British leaders should not be afraid to follow in this tradition.x More recently, of course, Tony Blair set out his ‘doctrine of the international community’ in his 1999 Chicago speech, a doctrine not dissimilar to the UN’s Responsibility to Protect. It may surprise realist critics that one of the five tests set out by Tony Blair for intervention was the involvement of national interests. The others were the certainty of the case, whether diplomatic options have been exhausted, our capacity to intervene successfully and our long-term commitment.xi

The debate about the direction British foreign policy should now take has, rightly, been raging in recent weeks around the cabinet table. Education secretary Michael Gove was most forceful in arguing that Britain should actively support pro-democracy protesters in the Middle East and should intervene militarily in Libya.xii The interventionists seem to have won the day, for now.

Interventionism in Libya and beyond

Of course, even though there is a political consensus in Britain in support of action in Libya, support for the idea of liberal interventionism in principle is far from being universally shared. Doubts and divisions about the operation in Libya are also emerging. It is vital that these divisions, within Britain and between the allies, do not prevent the operation being brought to a clear and successful conclusion. That must include Gaddafi no longer being in power in any part of Libya.xiii Otherwise, he will remain as a defiant, bitter and dangerous dictator who can claim victory against the West – much like Saddam Hussein after the first Gulf War. Rather than Libya becoming an inspiration to other countries where people want to throw off the rule of a dictator, Gaddafi will become an inspiration to other tyrants who will draw the lesson that they will be able to cling on to power if they are brutal enough, and the rest of the world will be powerless to stop them.

While regime change is not therefore explicitly mentioned in UN Security Council 1973, it must be our aim. Any result where Gaddafi remains in power will be an imperfect and temporary one, where Libyan civilians are left at risk. For this intervention to be successful, it cannot be half-hearted. Despite recent disputes over this, it is perfectly legitimate, and indeed sensible, to target Gaddafi’s command centre.xiv After all, if Gaddafi is not a legitimate target, then who is? Why is it legitimate to bomb a Libyan conscript soldier but not the dictator who is in charge of the slaughter? If we are serious about success, we should stop applying the arms embargo to the rebels. Gaddafi’s forces are already heavily armed, while the rebels are not, so the arms embargo leaves the rebels handicapped and – ironically – even more dependent on the NATO no-fly zone and aerial support. While the UN Security Council Resolution excludes an occupation of Libya, it is right that we have not arbitrarily ruled out any use of ground forces, no matter what the circumstances. Indeed, special forces have already been active on the ground. While maintaining an international and regional consensus is desirable, it should not be allowed to limit our ambitions and restrict our flexibility. The protection of the Libyan people is more important than trying to keep the UN, the Arab League or sceptical nations onside.

The principles applied in Libya should not be an exception, but rather the rule when dealing with dictators slaughtering their own people. We must watch the situation in Syria, where we have another potential case of a dictatorial regime with a record of exporting terrorism slaughtering its own people. The opposition protestors in Iran deserved greater support after the fraudulent election of 2009 than they got from the West, and they deserve our support now. We should not play down the threat from Iran, but should confront it head on, taking no options off the table, if we are serious about stopping the Islamic Republic from achieving nuclear weapons capability. Similarly in Afghanistan, we must continue to defend the evolution of democracy in the face of the onslaught from the Taleban, rather than focussing solely on our exit. A recently intercepted shipment of rockets from Iran to the Taleban underlines should serve as a reminder that the Islamist enemies of the West are interconnected and mutually supporting, and that Afghanistan is still on the front line of the struggle against them.xv Of course we must remain alert to the Islamist threat in Libya, Egypt and elsewhere, but this is not a reason to support dictators. Rather, it is a reason to support democrats, to insist on genuine democracy, as set out in the ‘Vision of a democratic Libya’ recently announced by the Interim Transitional National Council of Libya, and to ensure that democratic standards are abided by.

We must remain willing to adhere to the principle of intervention in defence of democracy and human rights – in Libya and beyond – if we are to avoid the mistakes of the 1990s when genocide and ethnic cleansing was allowed to continue without action from the West, and if we are to avoid a future where Britain and other Western nations fail to project democratic values overseas in the face of the rise of resurgent undemocratic world powers. By acting in Libya, Western leaders have chosen the right path. When we have the capacity to act to preserve life and defend human rights, then that creates the moral imperative to do so. If we are not willing to fight to defend democracy and human rights overseas, when we leave the path clear for despots and autocracy. Britain is one of the few Western countries with the capacity to play a leading role in large overseas military operations, and it is important that we fulfil our potential, as we cannot rely on other democracies to step into our place if we vacate it. Yet Britain is also in serious danger of doing long-term damage to its military capabilities through the defence cuts set out in the Strategic Defence and Security Review.xvi A glaring example is the lack of a carrier strike capability now that the carrier HMS Ark Royal and the Harrier jets have been decommissioned – in contrast to France, which has deployed the aircraft carrier Charles de Gaulle off the coast of Libya. If we are to continue to be able to respond to international situations as we have in Libya, then the decisions of the SDSR must be revisited.

Liberal interventionism has made a welcome return to the international arena, but this is just a beginning. For interventionism to be viable, it must be successfully implemented in Libya, and Britain and other democratic nations must maintain the military capability to act when it is necessary. While we have the United Nations on our side in this case, we cannot always assume that the Security Council will be supportive and we cannot allow that to dictate our foreign policy. Libya has shown, so far, that interventionism can be a powerful force for good. If we remain willing and able to project power overseas to protect democracy and human rights, including the right to life itself, then there is hope for the cause of freedom worldwide.

i David Cameron, ‘We cannot impose democracy at the barrel of a gun, The Independent, 5th September 2008, http://www.independent.co.uk/opinion/commentators/david-cameron-we-cannot-impose-democracy-at-the-

ii Robin Simcox, ‘David Cameron’s bad history’, Weekly Standard, 14th March 2011, http://www.weeklystandard.com/articles/david-cameron-s-bad-history_552974.html

iii George Grant & Alexandros Petersen, ‘Robert Mugabe will be watching Libya closely’, Daily Telegraph, 1st March 2011,

http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/africaandindianocean/libya/8354410/Robert-Mugabe-will-be-watching-Libya-closely.html

iv Alan Mendoza, ‘The UN is finally saving itself from disrepute’, The Times, 21st March 2011, http://www.thetimes.co.uk/tto/opinion/columnists/article2953659.ece

v Paul Kagame, ‘Rwandans know why Gaddafi must be stopped’, The Times, 23rd March 2011

vi House of Commons Hansard, 21st March 2011, http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201011/cmhansrd/cm110321/debtext/110321-0004.htm

vii Menzies Campbell and Philippe Sands, ‘Our duty to protect the Libyan people’ The Guardian, 9th March 2011, http://www.guardian.co.uk/commentisfree/2011/mar/09/our-duty-protect-libyan-people

viii Christopher Hitchens, ‘The Iraq Effect: If Saddam Hussein were still in power, this year’s Arab uprisings could never have happened’, The Slate, 28th March 2011, http://www.slate.com/id/2289587/

ix Michael Gove, ‘The very British roots of neoconservatism and its lessons for British conservatives’, in Irwin Stelzer (ed.), ‘Neoconservatism’ (2004)

x Brendan Simms, ‘What’s your foreign policy, Mr Cameron?, News Statesman, 17th March 2011, http://www.newstatesman.com/uk-politics/2011/03/british-essay-bosnia-democracy

xi ‘The Blair doctrine’, 22nd April 1999, http://www.pbs.org/newshour/bb/international/jan-june99/blair_doctrine4-23.html

xii Richard Seymour, ‘The siren song of the neocons in David Cameron’s cabinet’, The Guardian, 3rd March 2011, http://www.guardian.co.uk/commentisfree/2011/mar/03/david-cameron-neoconservative-cabinet

xii George Grant, ‘Why Colonel Gaddafi must go’, Daily Telegraph, 22nd March 2011,

http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/africaandindianocean/libya/8397636/Why-Colonel-Gaddafi-must-go.html

xiv Dominic Raab, ‘Is it legal to target Gaddafi?, Dom Raab’s blog, 23rd March 2011,

http://domraab.blogspot.com/2011/03/is-it-legal-to-target-gaddafi.html

xv Julian Borger & Richard Norton-Taylor, ‘British special forces seize Iranian rockets in Afghanistan’, The Guardian, 9th March 2011, http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2011/mar/09/iranian-rockets-afghanistan-taliban-nimruz

xvi Peter Cannon, ‘Britain’s Tied Hands’, Henry Jackson Society, 11th March 2011, http://www.henryjacksonsociety.org/stories.asp?pageid=49&id=1997