Bradley Manning And WikiLeaks: New Film By The Guardian Tells His Troubling Story – OpEd

To mark the first anniversary of the arrest of Pfc. Bradley Manning, the alleged whistleblower responsible for leaking hundreds of thousands of classified US military documents and diplomatic cables to WikiLeaks, the Guardian has produced a 19-minute film, “The madness of Bradley Manning?” telling his story, and including elements that have not been reported before.

Arrested in Kuwait on May 26, 2010, after computer hacker Adrian Lamo, with whom he had apparently been communicating about his activities downloading confidential material and handing it on to WikiLeaks, reported him to the FBI, Manning was held in solitary confinement in a military brig in Quantico, Virginia, for nine months from July 2010 to April 2011, when he was moved to Fort Leavenworth in Texas, where some social interaction is allowed.

The film is available below, as are cross-posts of two Guardian stories published to accompany it, Bradley Manning: the bullied outsider who knew US military’s inner secrets and Bradley Manning: fellow soldier recalls ’scared, bullied kid’.

In the film and the articles — and of importance, along with new revelations about aspects of Manning’s personal life and how he was bullied in the military, and should have been discharged because, as a former colleague explained, he was “a mess of a child” — are new details about the lax security in Iraq, where Manning allegedly downloaded the material that he later made available to WikiLeaks — in particular, former colleague Jacob Sullivan explaining, “If you saw a laptop with a red network wire going into it, you knew it was on SIPRNet. If you had the password you could access SIPRNet. Everybody would write their password on sticky notes and set it by their computer. There is no wonder something like this transpired.”

In addition, Peter van Buren, a civilian reconstruction team leader on the base, told the Guardian that there was “a sense of a security free-for-all about SIPRNet” (the Secret Internet Protocol Router Network, described by the US military (PDF) as “a system of interconnected computer networks used by the United States Department of Defense and the U.S. Department of State to transmit classified information (up to and including information classified SECRET).”

With these new revelations, the fears about Manning’s mental health while he was detained in Quantico, which sparked outrage in the US and around the world, and which I discussed in my articles, Is Bradley Manning Being Held as Some Sort of “Enemy Combatant”?, Former Quantico Commander Objects to Treatment of Bradley Manning, the Alleged WikiLeaks Whistleblower, On the Torture of Bradley Manning, Obama Ignores Criticism by UN Rapporteur and 300 Legal Experts and US Intelligence Veteran Defends Bradley Manning and WikiLeaks, are even more understandable, as he is clearly not someone of great mental resilience.

It remains distressing that he has had to wait so long for a trial, for which, as yet, no date has been announced, although he was initially charged in July 2010, and more charges were added in March this year, including “aiding the enemy,” which, theoretically at least, is a capital offense. As Wired reported last week, however, Adrian Lamo “is set to meet with the chief prosecutor on the case for the first time” on June 2, “mark[ing] the first outward sign that Manning’s court-martial case is proceeding apace now that a lengthy inquiry into his mental health has concluded.”

As Wired also noted, a military review board — known as a “706 board” — “had been requested by Manning’s attorney, David Coombs, to determine if his client suffered a ’severe mental disease or defect’” at the time he allegedly downloaded classified information and leaked it. Rather alarmingly, given what the Guardian investigation revealedabout Manning’s mental health, ”The board concluded late last month that Manning was mentally fit, clearing the way for an Article 32 hearing — the military equivalent of a grand jury — to determine if a court-martial trial against Manning should proceed.”

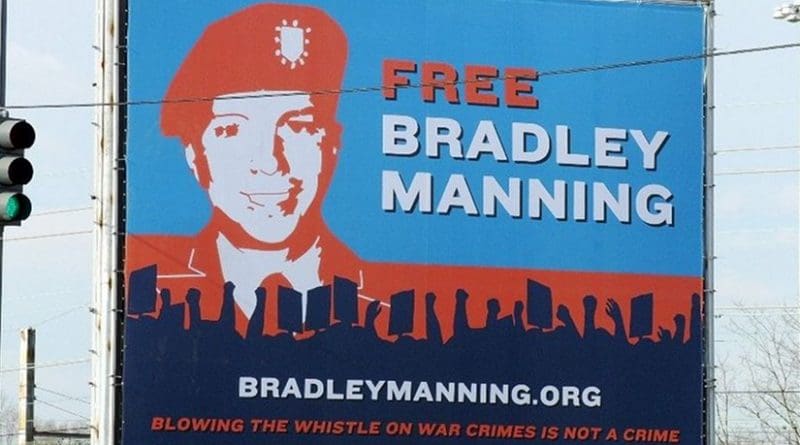

In the meantime, the Bradley Manning Support Network continues to publicize Manning’s unjust treatment. A rally will take place at Fort Leavenworth on June 4, and another creative campaigning initiative – I Am Bradley Manning — has also been launched, with supporters invited to submit messages and photos of themselves holding up cards stating, “I Am Bradley Manning.”

Bradley Manning: the bullied outsider who knew US military’s inner secrets

By Maggie O’Kane, Chavala Madlena and Guy Grandjean, The Guardian, May 27, 2011

Bradley Manning, the 23-year-old army private from Oklahoma alleged to have been behind the biggest US government leak of all time, is now in Fort Leavenworth military jail, Kansas. He faces 34 charges, and if convicted could face a prison sentence of up to 52 years.

So why did the US army ignore warnings from officers that Manning was unstable? Why did it send him — a 5ft 2in gay man with a history of being bullied in the military — to one of the most isolated and desolate bases in Iraq? Why was security so lax on the base that passwords for secret military computers were posted on sticky notes nearby?

A year after his arrest, a Guardian investigation reveals a trail of ignored warnings, beatings and failed personal relationships that led to Manning’s arrest on 29 May 2010.

Manning, the son of a former naval intelligence analyst, Brian Manning, and his wife Susan, was brought up in the small town of Crescent, Oklahoma. Neighbours watched the family disintegrate as Susan Manning turned to drink to ease the final years of the marriage.

“I never saw her plastered, but … I’d go by there at two o’clock in the morning and the lights would be on. I think she did her drinking when he’d go to bed,” one neighbour, Bill Cooper, said.

In 2001, when Manning was 13, his parents divorced and he moved with his mother to her home town of Haverfordwest, in west Wales, where he joined the local school, Tasker Milward comprehensive. Small, geeky and speaking with an Oklahoma accent, Manning was an obvious target for teasing, and he reacted furiously to it, friends recalled.

“Bradley’s sense of humour was different to the rest of ours, whereby the rest of the school kind of goad and tease each other,” said schoolfriend Tom Dyer. “He was far too literal for that, and so would often snap back if he thought the joke had gone too far, which would cause laughter for everyone else.”

When he was 17, by which time he was openly gay, Manning returned to Crescent to live with his father, who had remarried. The software job his father promised in Tulsa didn’t work out — and neither did his relationship with his stepmother and her son. “I am nobody now, Mom,” he wrote to his mother.

In March 2006 his stepmother called the police, saying that he was “out of control”. Manning left home, and for the next year slept on friends’ couches or in his pickup truck in other people’s driveways, earning money in a series of casual jobs in restaurants and coffee shops.

Manning was keen to work with computers but quickly realised there would be no job for him without a degree. Joining the US army, he decided, would be his best chance of getting one as they would help pay for it through the GI bill’s provision for soldiers’ education.

“He joined the army because he wanted to go to university,” said Keith Rose, a friend of Manning’s from time he spent in Boston.He said the army’s attitude towards gay people did not put Manning off. “I asked him that night how he could join, given the army’s attitude towards gays. He told me he was a patriot but there were benefits too. He wanted to go to university.”

In October 2007, Manning joined up. He was far from typical soldier material. He was smart, gay, physically weak and politically astute. “He knew all kinds of things,” said Rose. “He was heavily educated in science. He knew math. He knew what was going on in the world.”

He enlisted in October 2007 and was sent to Fort Leonard Wood, Missouri, for basic training, but in just over a month he was moved to a discharge unit and on the verge of expulsion.

One man who befriended Manning in the unit, but who wishes to remain anonymous, explained what being in the discharge unit meant. “He was not bouncing back. He’s going home. You don’t just accidentally end up in a discharge unit one day. You just have somebody one day saying, ‘You know what, he is no good — let’s get him out of here’. There are a lot of steps to go to before you even hit a discharge unit.”

Manning was picked on, the friend said, and used to wet himself. “[Once] there were three guys that had him up front and cornered. And they were picking on him and he was yelling and screaming.

“We got up there — it was me and a couple of the guys — and we started breaking it up. We were saying, “Get the hell out of there, back off,” and everything — and started pulling Manning off. The other guys were taking care of the ones that were picking on him and stuff. I got Manning off to the side there and yeah, he pissed himself. It wasn’t the only time he did that, but that was the only time that I remember. It happened a few other times, the other guys will probably tell you the same story. Just a different circumstance.”

Despite the concerns of his immediate superiors, Manning was “recycled” instead of being discharged. The war in Iraq was in its fourth year and the army was short of recruits.

In August 2008, after training as an intelligence analyst, he was stationed at Fort Drum in upstate New York while he awaited deployment to Iraq. Here he was considered a “liability” by superior officers.

His weekends at Fort Drum were occupied by visiting his first serious boyfriend, Tyler Watkins, a student at Brandeis University, near Boston. Watkins began taking Bradley to events at his university’s gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgender society, Triskelion, and introduced his computer-loving boyfriend to Danny Clark, a student at MIT. Through Clark, the Boston “hacktivist” scene — consisting of some of the world’s most prominent and smartest hackers — opened up to Manning.

Here Manning appeared to have found his place. He appears in photographs looking tanned and happy in Pika House, a clapboard communal student residence in the suburbs of Cambridge, Massachusetts.

The pictures appeared in a Facebook album Bradley captioned: “Randomly hung out with some pikans.” Bradley’s snaps were mostly of the tie-dyed T-shirt wearing Clark. The rest of the pictures are of the jumble of gadgets, electronics and posters that cover the house.

The day Manning was posted to Iraq in October 2009, Watkins went to a gay march wearing a placard that read “Army wife”. Manning was deployed to Forward Operating Base Hammer, one of the most isolated US posts in Iraq, in the desert close to the Iranian border. Veterans recalled a desolate place built mainly from freight containers.

“There was a fog that would come in almost every morning that was pollution from nearby that smelled sour and nasty, and would just wave through and linger,” said Jacob Sullivan, who served alongside Manning at Hammer.

Hammer’s overriding culture was one of boredom and casual bullying, where bored non-commissioned officers picked on juniors. “They had a saying, ‘Shit rolls downhill,’” said Jimmy Rodriguez, 29, an infantry soldier who was stationed at the base with Manning.

For entertainment, soldiers would download porn to workstations or access footage from Apache attack helicopters showing civilians being shot at, often through SIPRNet, the classified intelligence network used by the state department and department of defence.

It was data downloaded from this network that would later find its way to the whistleblowing website WikiLeaks.

According to Sullivan, security was extremely lax. “If you saw a laptop with a red network wire going into it, you knew it was on SIPRNet. If you had the password you could access SIPRNet. Everybody would write their password on sticky notes and set it by their computer. There is no wonder something like this transpired.”

According to Peter van Buren, a civilian reconstruction team leader on the base, there was a sense of a security free-for-all about SIPRNet.

“Soldiers would call it ‘war porn’ or ‘the war channel’ or just ‘war TV’. It was hypnotic to watch, even when not much was happening, just this lazy overhead view of the world around you. For many soldiers, it was all they ever saw of Iraq,” Van Buren said.

“I saw them using the SIPRNet for entertainment. That’s what most of the people did most of the time,” said Rodriguez. “They would watch these videos of different things and some of them were videos of helicopters attacking people or drones or whatever the case, or maybe fighter jets. But they were watching military footage.”

“We were pretty much bored all the time,” he recalled. “When you got to Iraq, we got to Baghdad and ended up in Forward Operating Base Hammer. They would [say to] us: ‘Here’s the videos; here’s the internet; here’s all the interesting games.’”

In January 2010 Manning went on leave and visited his friends in Boston, including Watkins. It became clear their relationship — one of the most significant in his life — was near its end.

That January, Rose recalled, “Bradley was really down. Tyler was like an anchor for Bradley and the one constant for that entire year. He gave me a two-hour earful about all the things in the relationship that he didn’t understand. He had gone in the military and come back and he didn’t have his relationship anymore.”

While his relationship with Watkins was souring, Manning socialised with Clark at the launch party for Builds — a hackers’ playground in Boston University’s computer science faculty where they would simulate unlocking codes and bypassing online security.

Film footage shows him leaning against a table — a soldier in his collared shirt, he looks very different from the grungy student hackers at a top university. Nevertheless, he appears comfortable inside this elite circle. Less than a week later, Manning was back at his intelligence analyst’s computer in Iraq.

“I live in a very real world, where deaths and detainments are just statistics; where idealistic calls for ‘liberation’ and ‘freedom’ are utterly meaningless,” Manning wrote in a final message to Watkins on Facebook. “I don’t have a real place to call home, except for a trailer with a bunk, a laptop, and an alarm clock. Please don’t let the LAST PERSON that I trust and care about go away. I haven’t given up.”

On 5 May he wrote of being “beyond frustrated with people and society at large”, and a day later, on 6 May, he wrote: “Bradley Manning is not a piece of equipment.”

On 7 May Manning was found in a foetal position in a storeroom after stabbing a chair with a knife as he tried to carve the words “I want” into the seat. He had punched his commanding officer, a woman, in the face.

He was disciplined and demoted and told he was to be finally discharged from the army on grounds of “adjustment disorder”. In the space of a few weeks, he had lost his job, his boyfriend and his chance of a university education.

During the following fortnight, Manning turned back to his computer and his hacker friends. He began chatting with someone who didn’t even know him, hacker Adrian Lamo.

In the early hours of 25 May, Manning had his last conversation with Lamo. The following day Lamo reported him to the authorities and he was escorted from his computer room. After three days of questioning he was charged in relation to the biggest intelligence leak in US military history.

The US military has refused to make any comment on Manning’s mental health record other than to confirm it is being investigated. He is due to be courtmartialled in December.

Bradley Manning: fellow soldier recalls ’scared, bullied kid’

The Guardian, May 28, 2011

Below is the transcript of an interview with a US soldier who was with Bradley Manning in the discharge unit of Fort Leonard Wood, Missouri, where Manning had been sent before he was due to be thrown out of the army in October 2007 — six weeks after he had enlisted. That decision was revoked and Manning ended up in Iraq.

Reporter: What’s the best way to describe you … How long did you spend with Bradley in discharge?

Soldier: Yeah, it was about two to three weeks.

Reporter: And you saw him daily, weekly?

Soldier: It was pretty much 24 hours a day as we were living together in the discharge unit of Fort Leonard Wood, Missouri.

Reporter: And when you say living together, how many people were in the discharge unit?

Soldier: The discharge unit [DU] at any given time had about 100+ men. It was basically one big room, it had a group of bunks, bunk-beds and that’s where we all lived.

He was being picked on — that was one part of it. Because you know Bradley — everybody said he was crazy or he was faking and the biggest part of it all was when rumours were getting around that he was chapter 15 — you know, homosexual. They’d call him a faggot or call him a chapter 15 — in the military world, being called a chapter 15 is like a civilian being called a faggot to their face on the street

The other part of Bradley’s outburst was withdrawing — because there wasn’t much of a happy medium. He was either all worked up or totally secluded — he didn’t really have very many moments of levity.

The kid was barely 5ft — he was a runt. And by military standards and compared with everyone who was around there — he was a runt. By military standards, “he’s a runt so pick on him”, or “he’s crazy — pick on him”, or “he’s a faggot — pick on him.” The guy took it from every side. He couldn’t please anyone. And he tried. He really did. You know what little interaction I had with him personally — it was like he was seeking approval. And he was really good with me but … there were three guys cornering him up front and calling him a chapter 15 — calling him a faggot. There were guys refusing to go in the showers when he was even in the damn latrine. I mean, it was childish and it was hateful and this guy wasn’t big enough to just stand up in your face and say: “Knock it off — quit picking on me”, and I’ll be damned but he tried. You know, there were several times which everyone called “emotional outbursts and tantrums”, but what it was was him saying, “Leave me alone.”

Reporter: What do you think about the idea that Manning was okay, wasn’t unstable? The army breaks people down — wasn’t he just as unstable as any other 18-year-old going through that process? Do you agree?

Soldier: No I don’t, I don’t agree with that at all. He wasn’t a soldier — there wasn’t anything about him that was a soldier. He has this idea that he was going in and that he was going to be pushing papers and he was gonna be some super smart computer guy and that he was gonna be important, that he was gonna matter to someone and he was gonna matter to something. And he got there and realised that he didn’t matter and that none of that was going to happen.

Reporter: Did you get the sense that he was disappointed because it wasn’t what he expected it to be?

Soldier: I never once got the feeling that he was disappointed because nobody noticed him. You noticed him. I mean, you could have picked him — within an entire formation of 160 people between the rehab side and the discharge side — in 160 people, you picked Bradley out first. He was the smallest. It wasn’t that he wasn’t noticed but that he was noticed too much.

Reporter: What’s it like to be gay in the DU — in practical terms?

Soldier: For Bradley, it was rough. To say it was rough is an understatement. He was targeted, he was targeted by bullies, by the drill sergeants. Basically, he was targeted by anybody who was within arm’s reach of him.

There was a small percentage, I’d say maybe 10-15 guys tops, who didn’t care what chapter he was, who just wanted to coexist until they could get out and just get along. But the rest of them — we’re talking mentally unfit. Some of them were there for criminal charges. Everyone who was there was getting kicked out. And between being mentally unfit and mentally unstable and being criminal, and then being locked in this room with the guys saying, “Oh, here’s this little guy” — it was open season on him. Being gay — being Bradley Manning and being gay in the DU — it was hostile. He was constantly on edge, constantly on guard.

Reporter: Why do you think he wasn’t discharged and what was your reaction?

Soldier: I was home for two or three weeks when I got a phone call from one of my friends who was actually still at the DU. He called me from a cell and he was giving me the updates, telling me what was going on and then he said: “Oh, by the way, Bradley is getting recycled.”

And I was in shock, I couldn’t believe it — there’s no way that this guy’s getting recycled — it wasn’t happening. And he was like, “No, he’s going back.” And I was like, “How does he feel about it?” and he said, “Oh, he’s great — you know, he’s happy about it.”

I don’t know how that happened, I don’t know when that happened because he didn’t want to be there and they didn’t want him there — he was going home. And then all of the sudden, I’m gone and I’ve gotta start hearing about how he’s going back. I was shocked and I was angry — I mean, not angry mad, but angry like frustrated and disappointed. You know, because the system failed, they let him down: he should never have been recycled.

Reporter: Why not? Would he not have a made a good soldier in the end?

Soldier: Bradley was not a soldier. Bradley was never a soldier. Bradley is never going to be a soldier. People who become soldiers are protectors, there’s a mindset to it. You know, Bradley wasn’t somebody (in my personal opinion and experience) who protects people, he’s not somebody who should be protecting people. He is somebody who needs protecting.

He’s not a soldier, he’s one of those guys that you watch out for and you take care of him. He’s not somebody I’d want next to me when I kick in a door. Bradley Manning was not one of those guys who you wanted next to you in a life or death situation. He wasn’t then and I don’t think he is now. I just keep seeing these pictures on the news and all these pictures on his Facebook, where they show him all smiles or with a slight smirk or he’s serious. All I ever keep seeing is this red-faced kid with bloodshot eyes just gritting his teeth and yelling and sweating. All I keep seeing is this scared kid. So it’s tough to describe…

They have all these beds and bunks that are all lined up and at the front there’s a common area. It’s not much of a common area but there’s a desk and doors, bathroom, storage room and then the entrance to this place. And there were three guys who had him cornered up front, and they were picking on him and he was yelling and screaming back.

And we got up there — it was me and a couple of other guys who went up there to start breaking it up — and I’m yelling, “Get the hell out of there, back off.” And I started pulling Manning off him while the other guys were taking care of the ones who were picking on him. And I got Manning off to the side and, yeah, he pissed himself — you know. That wasn’t the only time he did that, but that was the time I remember. It happened a few other times, I know a couple of guys who could tell you the same story, just different circumstances.

There were two occasions. One was when Manning was escorted to hospital for psych evaluation. They have what they call battle buddies. When you are on basic training you cannot go anywhere by yourself: you have to have someone with you at all times. One person. So, if you go anywhere you have to have someone with you.

When a chapter 15 has to go to see the JAG [Judge Advocate General] and have their teeth checked. When anybody goes anywhere in the entire discharge process, they have to have another soldier with them, a battle buddy. Nobody wanted to be Manning’s battle buddy. Nobody would escort Manning anywhere.

Why he was there in the first place in the DU, none of us know. They don’t tell the privates in the DU who is coming in today and here’s why they are coming in. It’s just, here’s new meat for the grinder for the most part. But the rumours were that Bradley was there because he was crazy. He was mentally unfit. I believe it was called chapter 17.

Reporter: Do you think his commanders should have kicked him out of the army? Should his commanders have spotted he wasn’t suitable and gone ahead with the discharge?

Soldier: They should have gotten rid of him. I do not understand the justification or what excuses they had to keep him around. He was a wreck, he was a complete wreck.

Reporter: Every single soldier at the end of basic training is supposed to be a wreck, are they not? Why was Manning different?

Soldier: The general concept of basic training is to take the citizen or take the boy, or the man, or the woman — take the person and break them down emotionally and rebuild them in the army’s image. I mean that’s basic training. There’s the mental break. Manning was not your typical mental break. It wasn’t a matter of I’m homesick or I’m a baby boy and I miss my Mummy. This was trauma. And the worst part about it is that the moment that anybody senses or sees weakness, it is like being in the water for sharks. I mean, they just dive all over it and compound it. You either bounce back from that or you don’t.

He was in the DU. That means he was not bouncing back. He was going home. You don’t just accidentally end up in a Discharge Unit one day. You have somebody saying, “You know what, he is no good — let’s get him out of here. There are a lot of steps to go to before you even hit a DU let alone before you from a DU to a bus or plane home. He wasn’t broken in the conventional sense, he was traumatised

Reporter: Why was it so traumatic for Bradley?

Soldier: He was small, he was gay and he was a gay in hiding. You don’t get into the military if you are gay. If you are gay and in the military, you lied to the military to get in. The recruiter told you, “Oh, don’t say that,” or someone coerced you and you ended up hiding that part of yourself. He was already a mess of a child to start with. Then you get him in there and expose him to sleep deprivation. When you are already unstable. When you are already incapable of having that mindset of suck it up and adapt and overcome. A soldier in basic training doesn’t know that they are a soldier — they just know they have seen one too many war movies, played one too many war video games or listened to Toby Keith too much.

Here’s the reality: basic training is, we build you down then we break you up — or we break you down and we build you up. Manning was not coming back up.

Reporter: You were just explaining to us the fact that you went through an experience that left you in the discharge bay as well, and that you are not mad at the army or the US government but you think there is something seriously wrong with a system that redeploys unfit soldiers. Could you just run that by me again?

Soldier: It’s not the redeployment, it is the recycling. There is something wrong with the system. First off, I was in the DU for a month and in that entire month not one person was recycled from the DU. When I got out, I went home and I was getting periodic phone calls from the guys. Bradley was the only one who got recycled. And like I said, for the life of me I still don’t understand how and why.

Anybody can figure out that this kid should not have been there. He didn’t have the mind or the mindset for it. A lot of hands were involved when it came to the decision of keeping him in. He was actually glad about the fact that he was going back.

Somebody managed to convince him or tell him the right story, or something so that he managed to end up being glad to be getting back in the system. I don’t know what happened. I don’t know what the trigger was. There are a lot of steps and people you have to talk to and things to sign and go through just to get from the barracks to a DU, let alone from the packet building in the DU to actually going home.

I think I am saying what is wrong with the system. Why was the US army in such a mess that they were recycling the likes of Bradley Manning?

I know for a fact that in 2007 recruiting numbers were the lowest they had ever been. They were lowering recruitment standards like crazy. I mean, facial tattoos, too tall, too short, too fat, criminal record — it didn’t matter. They even upped the age limit. You could be 42 years old and still enlist for basic training. It was take everybody you could get. Keep hold of everybody you can get. Bradley Manning should never have cleared any of those hurdles to even get into the military. And then he is in and it is a colossal failure and everyone knows it. And they say, right let’s get the ball rolling, file the paperwork and get him to a DU.

Discharge in the US army means fired. AWOL means “I quit” and the military would much rather have a higher number of people discharged than gone AWOL. Because with discharge they can say, “Oh well, they weren’t good enough so we got rid of them,” and the money keeps flowing in. Bradley should have been discharged, he was in the DU to be discharged. He was going home but they kept him in. Why did they keep him in, who thought that was a rational decision?

It went to the first sergeant and company captain. They signed off on it and the whole packet began. Physical doctors and mental health professionals failed on him. Then you have the cadres, the drill sergeants in the DU: they failed on him. The first sergeant and the company captain at the DU failed him. The judge advocate group that everyone in discharge had to go through, they failed him. That is a lot of people in a lot of offices and this is for a boy who is pissing his pants and curled up in a foetal position on his bunk and constantly screaming or in terror. There are a lot of people and a lot of steps that got missed. That’s what I am talking about with the system, or my frustration with the system and how all this happened.

And yet he was in a DU and the army almost got rid of him. You know, they have no one to blame for everything that’s going on except themselves. That’s the only reason I’m saying anything. I can’t help Bradley out. I tried to help him out then. A few others of us did but I can’t do anything to help him. I’m not doing anything to attack the army or the government or the system or anything. I’m just saying a lot of people let him down. He is not the first one they let down and he is not the last one. That shit is going on right now at Fort Leonard Wood, Missouri. It is going on at Fort Sill, Oklahoma and it is going on everywhere there is a training facility. I appreciate you guys taking the time.

You can’t get mad at the bull for wrecking the china shop when you have trapped the bull inside it. Bradley should never have been there. They had the opportunity to get rid of him and they didn’t. That was October and November 2007. It is now 2011 and all we are hearing about is Bradley, WikiLeaks, and he is the bad guy.

But the reality is that he should have never have been there. There are a lot of steps and a lot of people who let him down. Me and a few others in the DU tried to help him wherever we could. I’m not doing this because I am lashing out or I’m angry with the government or the system or anything else. I’m disappointed about the fact that no one has said anything to this day about how he was in a DU and that the army was going to fire him, they were going to get rid of him.