Will There Really Be A ‘New Settlement’ Between Britain And Europe? – OpEd

By EurActiv

By Andrew Duff*

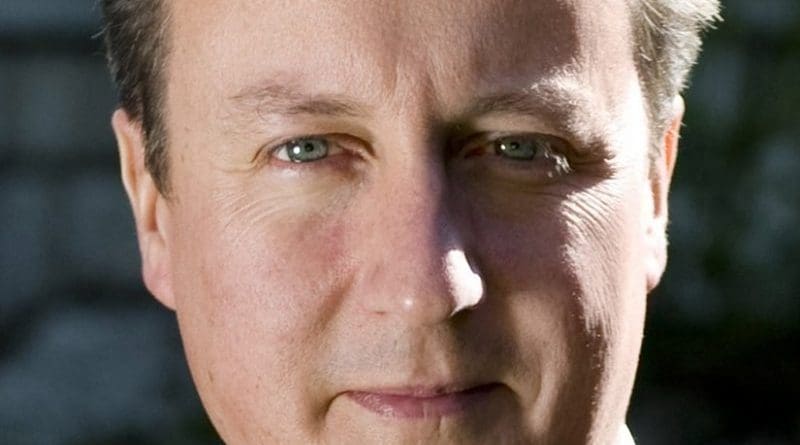

As the British referendum looms, a false sense of expectation is spreading in Brussels. Some wishful thinking is excusable: Britain’s partners have grown tired of having to tolerate David Cameron’s general contempt for the European Union and of circumnavigating his efforts to salvage the synthetic unity of his Conservative party.

It is clear that a British vote to leave the EU, triggering the secession process, will convulse the whole bloc at a time when it can ill afford another blow to its stability. What is much less clear, however, are the likely consequences of a vote to stay. For one thing, the UK will retain all its present opt-outs – from the euro and banking union, from Schengen and from common policy in justice and interior affairs.

The referendum campaign has had the effect of accentuating not reducing British exceptionalism: Cameron is the first British prime minister who says that sterling will never join the euro, and he goes unchallenged by ostensible pro-Europeans.

The UK’s hostility to European courts and fundamental rights has grown during the Brexit debate: Theresa May, Home Secretary, who will vote to stay a member of the EU, wants to withdraw from the ECHR. The prospect, always slim, that the UK can agree to the EU’s own accession to the ECHR is now further diminished.

On the back of a vote to remain, the UK will fight even more fiercely to protect its budget rebate and to block efforts at reform of the EU’s financial system. Britain’s self-exclusion from the EU’s efforts to resolve the asylum and immigration crises seems more determined than ever. The UK will continue to engage in EU common foreign and security policy only on matters of procedure, protocol and prerogatives, while largely avoiding substance. It will never participate in EU efforts in defence policy. It will block further EU enlargement.

If the UK votes to stay, the decision of the heads of state and government on 19 February for a ‘new settlement for the UK within the EU’ will have to be implemented. As was to be expected, the precise details of Cameron’s much-vaunted deal have played little to no part in the referendum campaign. Almost nobody can be found to support the prime minister’s claim that the deal has reformed the Union for the better. Yet his decision, conceded by the European Council, stands as a massive hostage to fortune.

In terms of secondary law the implementation of the decision will involve the complicity of the Commission and the assent via co-decision of the European Parliament, as well as the consent (tacit or not) of the Court of Justice.

The proposed legislative changes challenge at least three guiding principles of EU law: free movement of EU citizens, freedom to work and no discrimination on the grounds of nationality. Changing the rules to restrict in-work welfare (including child benefits) and to enlarge the rights of a member state to restrict immigration will be very complicated, controversial and protracted.

The irony will not be lost on EU law-makers that the changes contained in the decision are unlikely to make a significant difference to the numbers of people who want to live and work in Britain. MEPs will be split between left and right, nationalist and federalist, old and new, and East and West. This big legislative burden will be added to the pile of draft laws and hot political questions that the Commission has kept waiting in the wings until after 23 June including the follow-up to the Five Presidents’ Report on EMU, the refugee crisis, revision of the posted workers directive, the creation of capital markets union, reform of the budget and own resources system, and TTIP.

The decision also requires the EU to change its treaties to exempt the UK from the historic mission of ‘ever closer union’. The European Council, in its wisdom, has agreed that the Union shall no longer seek one political destination, but several. For the UK, apparently, it is to be ‘never closer union’; for the rest, however, the implications of ‘not ever closer union’ are just beginning to sink in. Who will be tempted to follow the example of the UK, entrenched in constitutional terms as a deviant member state?

All in all, it is difficult to avoid the impression that a Yes vote, especially if close, amounts to little more than a soft form of Brexit. The UK is set to continue to be a reluctant and detached member state of the Union, more often than not weakening the drift of common policy, diluting the force of EU law, and then dissembling about the outcome. The combination of the 2016 decision plus the EU Act of 2011, which imposes on the hapless British voter continuing referenda on all future European treaty change, risks making life nigh impossible for any future more ‘pro-European’ British government.

Can the curse of Brexit ever be dispelled? As a new collection of essays from the European Policy Centre by prominent British Europeans suggests, the UK has too often failed to fulfil the true potential of its EU membership. It would be a pity to go on repeating such dismal history.

In the short term at least, the status quo will not apply after 23 June. Things will not be back to normal. Britain’s ‘special status’, consecrated by a vote to remain, will mark a parting of the ways. It is greatly to be hoped that, whatever the outcome of the British referendum, the rest of the EU will exploit the new situation to make swift progress towards the deepening of fiscal integration without which the economic and monetary union will not be saved. (I have made my own proposals here.) Other shifts in competences upwards to the EU level, for instance in immigration policy, labour markets and energy supply, can follow on naturally from the qualitative move to fiscal and political union.

A new constitutional Convention will in any case have to be called to give effect to Cameron’s decision in terms of primary law, notably the opt-out of ‘ever closer union’. The Convention will be unable to avoid deep-seated democratic reforms to all the EU institutions. At that stage, the UK will have its last chance to discover a more truly European vocation, as the essayists in the new book advocate.

Unless the British find their European feet, it will be sensible and necessary to craft some novel form of EU affiliation for the UK, short of full membership. If a soft Brexit turns out to be what most Brits want, soft Brexit will need to be regularised in treaty form. Otherwise the British will for evermore impede the settlement of federal union. Who says the EU isn’t democratic?

*Andrew Duff was an MEP for the British Liberal Democrat party from 1999 to 2014 and a prominent member of the Constitutional Affairs committee in the European Parliament. He is a prominent voice within the European liberal ALDE family. ll opinions in this column reflect the views of the autho, not of EurActiv.com PLC, where this article first appeared.