50 Years Since 30 September, 1965: The Gradual Erosion Of A Political Taboo – Analysis

By ISEAS - Yusof Ishak Institute

By Max Lane*

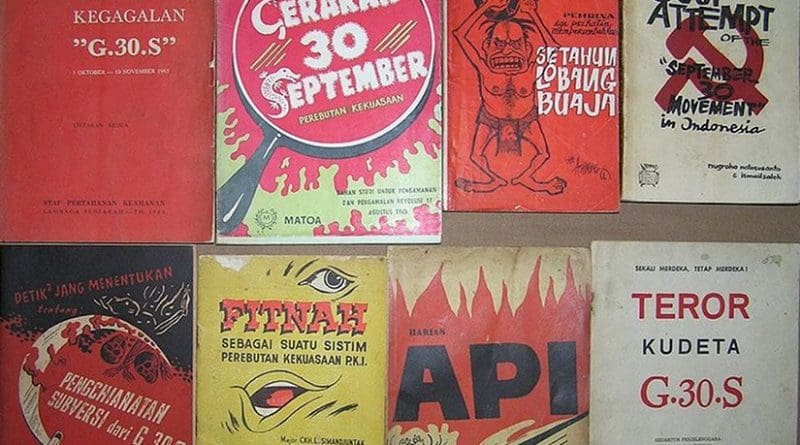

This year, 2015, marks the 50th anniversary of the events now known as the 30th September Movement – in Indonesian known as “GESTAPU” or “GESTAPU/PKI” or G30S/PKI. On the late evening of September 30 and into the next morning, several high-ranking Army officers were detained by officers and soldiers from the Presidential guard. The aim was apparently to present the generals to President Sukarno, accuse them of preparing a coup and seek their dismissal by the President. Sukarno eventually refused to support what they had done, especially after the killing of the generals, and ordered the movement to stop. The conspirators then escalated events, issuing a statement later in the day that the Cabinet of President Sukarno was decommissioned and a Revolutionary Council was being formed. As events unfolded, it became clear that the Chairman of the Indonesian Communist Party (PKI) was involved, although apparently without the knowledge of most of the rest of the PKI leadership1. By this time, however, on the afternoon of October 1, their moves had failed. As it collapsed, the detained Army officers were shot dead. The wing of the Army under Major-General Suharto seized the initiative and described the events as a coup attempt by the Indonesian Communist Party (PKI). A mass purge followed during 1965-68 and at least 500,000 members and supporters of the PKI and of President Sukarno, as well as alleged sympathisers, were killed.2

The 50th anniversary landmark has seen a substantial increase in public discussion of the 1965 events. This has been the case not only in Indonesia but also in academic and literary circles in Australia, the United States and Western Europe. The 1965 events were, for example, a profiled theme at the Frankfurt International Book Fair in October 2015, where Indonesia was the featured country.3 1965 was also the profiled theme at the Ubud International Writers Festival in Bali, October 2015 – although these sessions were later cancelled after talks with the local police.4 In Indonesia, many media outlets have published special features on 1965, including Tempo magazine5 and CNN Indonesia,6 with a wider range of views being presented than in the past, including the voices of the families of people who were killed and former political prisoners.

At official levels, there has been no change in the basic narrative constructed and used since the New Order period. President Widodo officiated at the usual October 1 ceremony, Pancasila Day, at the site of the executions of the Army officers with a speech focusing on the events of 30 September and October 1 and with no reference to the mass extra-judicial killings later on.7

Statements by other government officials and military leaders all reaffirmed the continued dominance of the old narrative.

But over time, there had emerged, even during the Yudhoyono presidency, pressure for a statement of apology by the state to those described as the “victims of the 1965 tragedy”. There had developed an expectation that President Widodo may make such an apology, where Yudhoyono had failed to do so. This expectation was fuelled by the fact that Widodo did receive support from people who had been campaigners for the cause of rehabilitation of 1965 victims. Major institutions such as the National Commission on Human Rights (Komnas HAM), a statutory body established by legislation with commissioners selected via the parliament, had also urged for such an apology to be issued by President Widodo.8 Komnas HAM has been advocating for a general approach that would achieve “reconciliation” with the victims. It has also been concerned about the slow discussion in parliament of a bill to establish a truth and reconciliation commission to deal with 1965 and its aftermath.

However, it became very clear by September 2015 that President Widodo was not considering such an apology or any major gesture towards reconciliation. In September he met a delegation from the Muhammadiyah organisation. After the meeting, Abdul Mu’ti, the organisation’s Secretary General, told the media that the President had clarified that no such apology would be made and that indeed he had never had the intention to make such an apology.9 This position was reaffirmed clearly again on October 1 at the official state ceremony held at the site of the mutineers’ execution of the army officers.10 Widodo’s statements echoed a longstanding official narrative that is still embodied in all published government materials on the 1965 events and in many school textbook accounts.

GRADUAL EROSION OF HEGEMONY

At the same time, there has nevertheless been at least the beginning of an erosion of this hegemony in society at large, although not at a mass level. The fall of Suharto and his general delegitimation in the public eye did, of course, start the process. This delegitimation of Suharto, moreover, was immediately associated with the collapse of the official ideology. Even the massive effort surrounding Pancasila indoctrination appeared to have shrivelled and lost energy, even if it retained its official position. There were also specific concrete government- level decisions made during the first few years after the fall of Suharto which have facilitated this process of the erosion of hegemony.

One of the first was the decision to stop screening the classic propaganda film “Pengkhianatan G30S/PKI” (The Treachery of G30S/PKI). This is a three-hour feature film, effectively directed with high production values by one of Indonesia’s leading playwrights in the 1970s, graphically and bloodily depicting the full New Order version of what happened on 30 September, including the torture of the executed army generals by sex-crazed communist women. The film was screened annually in cinemas and school children were taken en masse to see it – for millions in small towns and villages their first cinema experience. It was also screened on television annually. For young people in the 1970s and 1980s, it completely defined their knowledge and convictions as to what happened in 1965. As early as July 1998, with B.J. Habibie still President, a decision was made not to screen the film on 30 September. Interestingly, it is reported that it was military officials who first made the suggestion. Air Force leaders did not like the way the film depicted Air Force complicity in the 1965 events. An army general complained that the suppression of the 30th September Movement was too centrally attributed to the figure of Suharto.11 It is now 17 years since the film has had any systematic screening, meaning that several generations of school children have had no exposure to it12.

A second government-level decision which has facilitated the erosion was changes to the official school curriculum for history that was initiated during the Presidency of Abdurrahman Wahid. After 2001, the curriculum was revised to allow for five different analyses of what happened in 1965 to be taught. New text books appeared in 2004. In the new curriculum, the 30th September Movement was also no longer referred to as G-30-S/PKI, but only G-30-S. The institutionalised identification with the PKI was ended. The five different analyses were drawn from the existing international scholarship around these events. This ended the 40-year period when only one (official) version of the events was taught and which had to be learned by rote. Alternative versions included those that argued that 30 September was an internal affair of the army and not a PKI initiative13. This was a daring inclusion at the time, as was the introduction of the mere idea that there could be multiple interpretations.

During the Yudhoyono Presidency, in 2007, after campaigning from leading intellectuals from the 1966 Generation (the initial intellectuals who supported the New Order), this change was annulled and the curriculum reverted to referring to G-30-S/PKI14. The earlier text books were recalled and burned. It is not clear to what extent there was internal debate on this issue. The decision most likely reflected a passivity among the state elite when confronted with an active defence of the old hegemony.

Automatically, with this change, the tendency was again to return to a single-version approach. It is not clear how quickly the teaching of multiple versions ended after this, but it would appear that, for several years, students – not to mention teachers and student teachers in universities – were exposed to new ideas about what happened in 1965. The version allowing discussions of alternative analyses was in circulation for at least ten years, before it was replaced. This means that hundreds of thousands of children went through school free of the single-version syndrome. In teacher training universities, the more open approach was also widely utilised.

In October 2015, even while there have been several cases of pressure to curtail discussion of 1965, there have been some reports that new text books will again allow discussion of different versions of what happened on 30th September 1965. In a report in Republika newspaper, a member of the team writing a new official school text book, Linda Sunarti, head of the History Department at University of Indonesia, explained that the text book would also contain various versions, although it is not clear how extensive that range will be. She also explained that schools were also free to use other books to discuss 1965.15

An additional factor weakening the ideological weight of the single version in schools, even after it was reintroduced,16 was changes in the general educational philosophy. New guidelines on pedagogical outcomes include specifying analytical and research capacity. Interestingly, Sunarti, in the report above, also said teachers should encourage their students to investigate what happened in 1965 by interviewing their grandparents. This moves the overall approach away from the New Order rote-learning methods. This has meant that innovative teachers have been able to set research tasks for students on historical events, who can then use the Internet to obtain wider data and a wider range of analyses. It is not clear that this latter practice is widespread in Indonesia’s massive school system, however given that many young teachers were university students during the period of student protest against Suharto in the 1990s, there are indications that such critical teaching is occurring at least among an active minority17.

NON-STATE PROCESSES

Apart from the abovementioned decisions made by government, initiatives from outside the realm of the state and from semi-state institutions have also furthered the general erosion of the New Order’s hegemony. The work of Komnas HAM has been important. In July, 2012, it issued a report entitled “Statement by the Human Rights Commission on the Investigation Results Into Serious Violations of Human Rights connected to the Events of 1965-66.” Komnas HAM, established by legislation as a state-funded body, in its report identified cases of murder, torture and enslavement and argued that it was the state apparatus including the military that needed to be held accountable.18 The report was handed to the Yudhoyono government and also made available publicly. It fuelled the energies of those arguing for a reconciliation process, an end to impunity in the legal system as well as a statement of apology. However, to date, there has still not been any serious governmental response to the Komnas HAM report. Its real impact was in adding legitimacy to the discussions in society around this issue. School students researching 1965 on the internet could easily find the Komnas HAM documents.

Moreover, especially over the few years leading up to the 50th Anniversary, but also earlier, there has been more activity by victims themselves and human rights groups around these issues. There are more than one association of 1965 victims who have held public forums and meetings to advocate the return of their rights and rehabilitation19. Some have also been active in uncovering mass grave sites. This activity started more openly after Suharto fell – although there had been activity by a few groups before that. These activities have sometimes been harassed by small but militant anti-communist and religious groups, but they have continued and generated press coverage, heightening the interest20. There have also been important documentary film releases on 1965 which have helped generate discussion. One of the first and most important of these was “A Gift for the Indonesian People”” made by Danial Indrakusuma and which won a prize at the 2003 Jakarta International Film Festival.21 This has been widely screened in different non-commercial venues and has been made available on YouTube.

More recently, the documentary film The Act of Killing by Joshua Oppenheimer and its sequel, Look of Silence, have generated considerable discussion in the Indonesian press and social media22, despite not being allowed to be screened in commercial cinemas or on television. Screening has again been limited to voluntary, non-commercial venues. Both films are easily available on the internet. In response to The Act of Killing, major publications, like TEMPO magazine, also published their own special features on the mass killings23.

This year, civil rights lawyers and activists, led by former National Awakening Party (PKB) Member of Parliament, Nurysahbani Katjasungkana, organised an event described as an International Peoples’ Tribunal to investigate serious human rights violations in 1965.24 This project organised forums and events in Indonesia as well as in the Netherlands. In November 10-13, it organised in Den Haag, the Netherlands, a panel of respected international jurists and researchers to hear evidence presented by a team of lawyers from Indonesia, headed by prominent corporate and human rights lawyer, T. Mulya Lubis25. It provided documentary evidence to the panel and had three days of hearing of witnesses organised by the legal team from Indonesia. The panel concluded that the Indonesian state did have to answer for gross violations of human rights in 196526. It was widely reported in Indonesia, eliciting mostly hostile responses from members of the government, some of whom threatened to “put the Netherlands on trial for past human rights violations in the colonial period”27. Meanwhile commissioners representing both Komnas HAM and Komnas Perempuan28 also attended and gave evidence supporting the accusations against the Indonesian state 29 .

Supportive commentary was visible on the social media and in segments of the Indonesian press3031. It certainly helped profile this issue nationally and internationally during this immediate period.

In addition, many other human rights NGOs and individual activists have campaigned on this issue over the last few years.

Very symbolic of the process of hegemony erosion has been the popularity of an internet video: “Many Indonesians hate communism without knowing what it is.”32 It was created by a well- known stand-up comedian and IT graduate from Bandung, who already had a standing as a satirist. The video had 22 thousand Facebook likes just on its own page, let alone as the consequence of being reposted and shared via Facebook and blogs. It is a cogent satirical critique of the existence of a hegemonic version of history advocated by the state. The comedian does not argue for the replacement of the current version of the 1965 events with another, but rather that society be allowed to judge the various explanations on the basis of evidence and logic.

IDEOLOGICAL HEGEMONY REMAINS: BUT UNDER A STATE WITHOUT IDEOLOGICAL FOCUS

President Widodo’s business-as-usual approach on October 1 indicates that at the state level whatever the erosion of the hegemony of the old narrative in society, it is not yet impacting on government. Indeed, other incidents after October 1 include the arrest and deportation of Tom Iljas, an exile who had returned to Indonesia to find the mass grave where his father was buried.33 In the city of Salatiga, a campus student newspaper was seized and ordered burned because its front cover story was on the 1965 events, featuring a photo of a PKI rally in the town in the 60s.34 The sessions at the Ubud Literary Festival on 1965 were cancelled, after pressure from the police. The one-version-of-history approach remains the formal position within the education system, even though it is being subverted in practice in a still limited way35.

The State’s formal position, however, cannot stem the erosion of hegemony. The current state is unfocussed when it comes to ideology. It allocates very little resources to imposition or simply winning support for any specific ideological perspective: it is almost a-ideological. A part of the reason for this is that much of the ritual and ceremony connected to the events of 1965 had a special weight during the New Order as they were connected to its birth. The fall of Suharto and the start of the Reformasi era has produced new Reformasi “creation stories”.

Few serious resources are invested in coordinated state ideological activity. A part of the character of the New Order was its opposition to high levels of ideological contention, which had characterised the preceding 1945-65 period. Its answer was the imposition of a single state ideology, requiring severe central control and the deployment of substantial resources from the centre. While many of the institutions and even laws connected to this still exist, post-Suharto governments have not prioritised this activity, although they had maintained an allegiance to the content of the previous ideology, in particular in relation to 1965.

In the post-Suharto period, however, there has been a shift from defending the centralised ideas of Pancasila Democracy to at least the ideological commitment to electoral democracy, which, in itself, encourages, at least at a formal level, the idea that politics is about contention and thus does not encourage hegemonic versions of history. This is clear also in the education system. A text book version of the official narrative has much less impact in a society where the state has effectively vacated the ideological arena, relying for its legitimacy on delivering pragmatic material outcomes.

There can be little doubt that a process has begun which is opening up a gap between the official state-sanctioned hegemonic narrative of 1965 and the discussion – however embryonic at this point – in society. What is still unclear is how fast this process will develop and as the hegemony erodes what new ideas will replace it or at least vie with it. At the moment, the process is driven by a relative lack of interest and deployment of resources by the state in ideological matters, in particular the origins of the New Order in 1965, combined with increased activity by concerned groups and individuals. To date, no organised, substantial section of society, as a social force, has taken on a campaign against the existing hegemony. While this may be the case, the erosion of the old hegemony is likely to continue at a slow pace, marked by ongoing but uneven attempts to halt this process, by elements in government and society still convinced of the New Order perspective.

About the author:

*Max Lane is Visiting Senior Fellow with the Indonesia Studies Programme at ISEAS- Yusof Ishak Institute, and has written hundreds of articles on Indonesia for magazines and newspapers.

Source:

This article was published by ISEAS as ISEAS Perspective 66 (PDF).

Notes:

1 I am using the research available in the most recent book-length academic account of the events of the evening and September 30/October 1, namely John Roosa, Pretext for Mass Murder. The September 30th Movement and Suharto’s Coup d’État in Indonesia, University of Wisconsin Press, 2006. (There has been more recent publications looking at the mass killings after 1965, but they do not research the actual events of the 30 September and October 1, 1965.)

2 ibid

3 http://www.indonesiagoesfrankfurt.net/tragedi-1965-indonesia-dan-dunia/

4 http://www.ubudwritersfestival.com/message-uwr-founder-director/

5 https://majalah.tempo.co/site/2015/10/05/867/cover3244

6 http://www.cnnindonesia.com/nasional/focus/setengah-abad-selepas-g30s-2765/all

7 http://nasional.kompas.com/read/2015/10/01/08463301/Jokowi.Pimpin.Upacara.Hari.Kesaktian.Pancasila.di.Lu bang.Buaya

8 http://www.bbc.com/indonesia/berita_indonesia/2015/09/150921_indonesia_lapsus_kasus65_komnasham

9 http://nasional.kompas.com/read/2015/09/22/11593891/Kepada.Muhammadiyah.Jokowi.Bantah.Akan.Minta.M aaf.Terkait.Masalah.PKI ; http://kabar24.bisnis.com/read/20150928/15/476652/soal-pki-presiden-joko-widodo- tak-ada-rencana-minta-maaf

10 The officers were mainly shot and then thrown down a well. Official Suharto era propaganda also claims that the generals were tortured, included sexually, before being killed. But the official autopsy of their bodies indicated no such torture took place. See Steven Drakely, Lubang Buaya: Myth, Misogyny and Massacre, International Institute for Asian Studies, http://www.iiav.nl/ezines/IAV_607294/IAV_607294_2010_3/Drakeley.pdf, December, 2007.

11 http://nasional.tempo.co/read/news/2012/09/30/078432829/tokoh-di-balik-penghentian-pemutaran-film-g30s 12 Feature movies, in the cinema and on television, are also much more widely accessible today than in the 1970s, and audiences would be much more discerning in determining what is truth and what is fiction.

13 This version was drawn from B. Anderson and R. McVey, A Preliminary Analysis of the October 1, 1965, Coup in Indonesia Cornell University, 1966.

14 Paige Johnson Tan, “Teaching and remembering”, in Inside Indonesia 92: Apr-Jun 2008 – http://www.insideindonesia.org/teaching-and-remembering

15 http://nasional.republika.co.id/berita/nasional/umum/15/10/01/nvjvtr254-beragam-versi-g-30-s-ada-dalam- buku-sejarah-siswa.

16 The exact timing of the reintroduction is somewhat unclear. Certainly by 2013, teacher training universities had received memorandum ordering the withdrawal of the earlier multi-analysis text books.

17 These observations are partly based on discussions, including workshops, with lecturers in history education and with high school history teachers held at the Universitas Negeri Yogyakarta, a teacher training university, between 2013 and 2014.

18 PERNYATAAN KOMNAS HAM TENTANG HASIL PENYELIDIKAN PELANGGARAN HAM YANG BERAT PERISTIWA1965-1966, July 2012, http://www.komnasham.go.id/sites/default/files/dok- publikasi/EKSEKUTIF%20SUMMARY%20PERISTIWA%201965.pdf

19 The most prominent has been the Yayasan Penelitian Korban Pembunuhan 1965-1966, see http://ypkp65.blogspot.com.au/ In an earlier period the Institut Sejarah Sosial did oral RESEARCH AMONG VICTIMS OF THE VIOLENCE IN 1965, SEE http://www.sejarahsosial.org/

20 For example in 2015 see http://www.merdeka.com/peristiwa/kongres-anak-korban-65-batal-gara-gara- ancaman-diserbu-ormas-islam.html

21 http://www.suaramerdeka.com/harian/0303/27/bud1.htm see also https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=s- 6Bk5wJHks

22 For a selection of Indonesian comments chosen by the filmmakers see: https://m.facebook.com/notes/film- senyap-jagal/komentar-di-indonesia-tentang-jagalthe-act-of-killing/247886462001186/ A google search in Indonesian for “film JAGAL Oppenheiomer” reveals hundreds of media and social media reports and posts.

23 http://nasional.tempo.co/read/news/2012/10/01/078432913/para-jagal-dari-tahun-yang-kelam – This issue has a special feature on this question.

24 http://1965tribunal.org/a-peoples-tribunal/

25 The Tribunal has a comprehensive website at http://1965tribunal.org/. For a while it seemed to be blocked by undetermined hackers.

26 http://1965tribunal.org/concluding-statement-of-the-judges/

27 http://jakartaglobe.beritasatu.com/news/government-rubbishes-independent-hague-tribunal-1965-massacres/; http://www.bbc.com/indonesia/berita_indonesia/2015/11/151111_indonesia_luhut; http://news.liputan6.com/read/2362889/tantangan-jk-untuk-belanda-jika-gelar-pengadilan-ham-kasus-65;

28 National Commission on Violence Against Women.

29 http://1965tribunal.org/id/dua-anggota-lembaga-negara-tampil-dalam-sidang-ipt65/

30 There were also hostile reactions from organisations supporting the establishment of the New Order in 1965, such as the Nahdatul Ulama and Himpunan Mahasiswa Islam. See http://berita.suaramerdeka.com/rugikan- bangsa-pbnu-siap-lawan-ipt-1965/ and http://mataindonesianews.com/hmi-ipt-65-dinilai-melanggar-ham- terhadap-umat-islam-indonesia/. It is difficult to ascertain how widespread support for such responses would be in the activist base of these organisations.

31 http://jakartaglobe.beritasatu.com/opinion/johannes-nugroho-knee-jerk-reactions-ipt-1965-will-not-help- indonesia-one-bit/. For examples of sympathetic reporting, see the news, articles and opinion sections posted on the IPT Tribunal website.

32 http://www.rappler.com/indonesia/107627-indonesia-benci-komunisme-sammy-notaslimboy

33 http://nasional.tempo.co/read/news/2015/10/18/078710584/kisah-tom-iljas-diusir-dari-indonesia-karena- ziarah-ke-makam-orang-tua

34 http://nasional.tempo.co/read/news/2015/10/19/063710802/lentera-dibredel-aji-kecam-polisi-ini-insiden- memalukan

35 This can be seen, for example, in the BUKU SEJARAH INDONESIA, published by the Ministry of Education for the 2013 Curriculum (now suspended for all subjects” on page 107 where the G-30-S/PKI term is used, but with no discussion of different versions. However, as pointed out above, teachers may also use other books and set research projects. This document can be found at http://www.slideshare.net/bpangisthu/sejarah- indonesia-kelas-xii-k13-buku-siswa.