COP-23 Climate Negotiations: Politics Over Just Commitments – Analysis

By IPCS

By Garima Maheshwari*

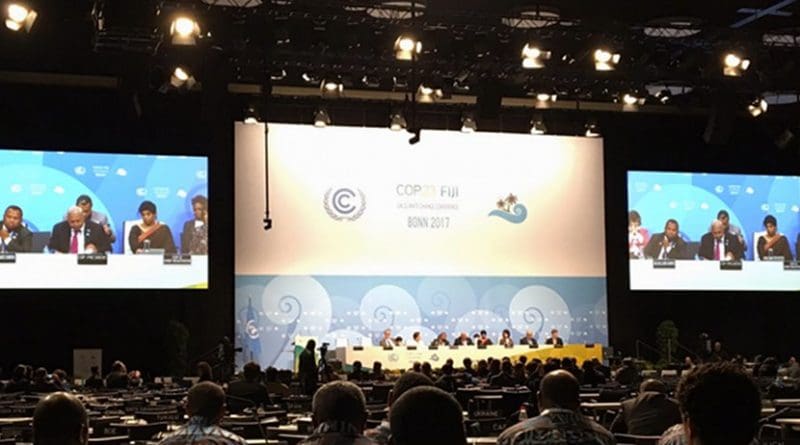

What was expected and proclaimed to be a rather technical working conference to hash out the rules for 2018 is turning out to be a political minefield with the potential to undermine the very basis of ‘climate justice’ that has formed the core of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) since 1992. On the very first day of COP-23, at the plenary session itself, the presidency held by Fiji has backtracked on the pre-2020 promises to the majority of developing countries, grouped under coalitions like ‘like minded developing countries’, ‘BASIC (Brazil, South Africa, India and China)’ and G-77+China. Fiji twisted the hard-fought inclusion of ‘pre-2020 commitments’ on the COP-23 agenda and declared that they would not be discussed in the main negotiations.

Under the Kyoto Protocol’s second commitment period, the pre-2020 commitments obligate the developed countries to meet their mitigation targets and also provide ‘mean of implementation’ – like finance, technology and capacity-building – to developing countries. Post-2020, as envisioned in Paris, even developing countries would be nearly equal partners in mitigation. The understanding that the pre-2020 commitments would be fulfilled had allowed for consensus on discussing ambitious mitigation commitments by developing countries.

The commitments arising out of historical responsibility of the developed countries forms the core of climate justice, hard-won by developing countries since 1992 under UNFCCC. India, China and others have always been clear that the Paris Agreement falls within the UNFCCC, and yet the attempt now is to subvert the principles of UNFCCC itself. One wonders why Fiji is playing this politics. The island nation wants the temperature limit controlled up to 1.5oC above pre-industrial levels; and for that, ambitious mitigation action is necessary. Although this can be justified, would it not make more sense to compel the developed countries to stick to their mitigation targets and other commitments (since that would also incentivise developing countries to ramp up climate action)?

This would have been the most rational course to take for Fiji and it would have kept all parties on board, instead of alienating a whole section of developing countries and the African group of least developed countries that acutely needs the finance. It would have cohered with Fiji’s understandable ambitions to leave a mark or a legacy on the COP. The only explanation for Fiji’s hostile turnaround is that it has joined forces with the developed countries’ bargaining positions.

This politics renders the term climate justice vacuous and vulnerable to political appropriation. The term is often used loosely in the COPs, and the implications of each definition would be very different. It has become even more vacuous and narrowly quantified ever since the Paris Agreement provided breathing space to countries. While everyone was complacent at Paris (despite its weak climate pledges), now the whole thing seems to be backfiring and threatening the very nature of climate regime built over the last 25 years.

This space is being utilised by advanced historical emitters and developing countries alike. For the advanced historical emitters, attempting to avoid pre-2020 commitments and focusing mainly on mitigation actions after 2020, would solve the purpose of letting the advanced polluting economies go scot-free on their earlier commitments as well as avoid the tricky issues of finance and technology transfers by privileging mitigation over adaptation.

Developing countries appear cornered for now. From the way the current political positions are panning out, even speculations about China assuming leadership at Bonn seem exaggerated. Countries’ political positions are determined more by their alliances and less by sincere climate action back home. In fact, in the latter case, India is about to meet its 2030 commitments, but the vexatious politics at UNFCCC is far from being in India’s favour. China may have allied with the US at Paris, but right now the usual multilateral voice of G-77 and ‘like minded developing countries’ would likely predominate. Nevertheless, these countries will find themselves on the backfoot in the mitigation debate.

They may refuse to cooperate altogether on the post-2020 Paris agenda if the pre-2020 commitments and mobilisation of finance is not done. By also stressing that adaptation is a priority for developing countries, the adaptation versus mitigation debate threatens to lock down critical aspects of negotiations. This would be a loss for the island states. The G-77+China and the island states have a lot to share – including critical issues like mobilising finance for the Warsaw Mechanism on Loss and Damage (which has been perennially stuck because of developed countries’ resistance). Therefore, alienating the developing countries under the delusion that ambitious mitigation action is possible by allying with the developed countries will only obstruct climate action further. Disasters due to climate change are a reality and current pledges and measures can only be temporary palliatives, but even so, to bargain over the bare minimum of commitments shows that climate inaction is here to stay.

* Garima Maheshwari

Researcher, IReS, IPCS