Role Of Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region In Economic Security Of China – Analysis

By JTW

By Altay Atli*

The Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region is territorially the largest administrative unit of China1, covering around one sixth of the country’s total area, and neighboring eight independent countries (Afghanistan, India, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Mongolia, Pakistan, Russia, Tajikistan). The region was under the spotlight of the world during the summer of 2009 when clashes between the two major ethnic groups, Uyghurs and the Han Chinese, left around 200 people dead in Urumqi. In their attempts to explain the violence in Xinjiang, most analysts overplayed the ethnic factor, largely ignoring the socio-economic context within which the ethnic structure of the region should be evaluated. Evidence suggests that the leading cause of the instability in Xinjiang is not the failure of different ethnic groups to coexist, but mainly the relative economic backwardness of the region, which results in large income disparities between these groups, creating a fertile ground for unrest, one that is further worsened by the ethnic policies adopted by the central government in Beijing.

At the same time, it has to be admitted that the central government has been heavily investing in Xinjiang’s development over the past decade. There are continued economic reforms accompanied by limited cultural and political openings, and as David Gosset argues, “in a fragile macro-region, Xinjiang stands, by sharp contrast, as a pole of stability and economic development.”2

The main question addressed in this article is why the economic development of Xinjiang is a priority for the Beijing government. As will be discussed below, most scholars and China-watchers approach this issue by emphasizing the intention of Beijing to keep ethnic separatism at bay. The situation is often portrayed as a Faustian bargain, in which Beijing provides the ethnic groups with greater welfare, asking them in return to give up their demands for political freedom. However, this line of reasoning leads to a serious dilemma: If this is the primary motivation of the government, how can we explain the fact that Beijing’s investment in Xinjiang is much higher than its investment in other regions populated by predominantly non- Han Chinese population?3

In order to understand Beijing’s determination in economically developing Xinjiang, we need to go beyond the ethnic issues and consider the case of Xinjiang within the larger framework of China’s economic security. The Chinese economy is growing rapidly and so are its requirements and needs, including but not limited to raw materials and resources. Xinjiang’s geographical position as China’s gateway to Central Asia and its endowment of natural resources make it an important actor in this respect. In order to illustrate this argument, this article will first discuss what economic security means in the Chinese context, provide brief background information on Xinjiang’s economic development, and then proceed to evaluate the region within the Chinese context in order to assess to what extent Xinjiang contributes to the overall economic security of China. In this way, this article hopes to shed light on the motivation behind the Chinese government’s intensive efforts for developing this region.

- The question is, why does Beijing invest in Xinjiang?

- Is it because Beijing wants to improve the living standards of the people living in Xinjiang?

- Is it because Beijing wants to prevent ethnic separatism in Xinjiang?

- Is it because Beijing wants to establish a buffer against Central Asia?

- Is it because Beijing wants to source raw materials from Xinjiang for the rest of the country?

Whereas all of these questions can be responded to in the affirmative, Beijing’s motivation for investing in Xinjiang should be evaluated within the larger framework of the “economic security” concept. This paper argues that Xinjiang’s development is of vital importance for the central government because this region is playing a key role vis-à-vis the economic security of China. Before moving to elucidate this argument, we will first discuss what economic security means in the Chinese context.

1. China and the Concept of Economic Security

The current era of globalization, marked by growing economic interdependence among countries, has given rise to the necessity of redefining the concept of “security”. As greater openness and interconnectedness brought about higher degrees of economic volatility, uncertainty, and vulnerability, traditional security perceptions such as interstate military conflict came to be replaced by not only non-conventional forms of violence such as global terrorism, but also by economic security concerns. As a result, scholars began to pay greater attention on issues related to economic security. In one of the groundbreaking studies in this field, Barry Buzan looked at the main features of new patterns of global security relations. Accordingly, the changes in security relations between the center and the periphery were happening in five sectors: political, military, economic, societal and environmental.4 Buzan defined economic security as being “about access to resources, finance and markets necessary to sustain acceptable levels of welfare and state power.”5

Another development with regard to the literature on economic security was the diversification of regions analyzed. Whereas in past decades scholars mostly dealt with developed countries and particularly the United States, there emerged lately a greater interest in the developing parts of the world, where globalization and the challenges it brought led to a redefinition of the economic security concept in an on-going process. China is one of the countries where this redefinition has been most dramatic, since in China globalization has coincided with the opening up of a socialist economy and the consequent rapid growth. China’s economic growth is remarkably impressive by any measure and it is fair to say that China’s growth is one of the most important factors shaping today’s global economy. However, on the other side of the coin, the issue of economic security raised by China’s rapid growth remains as a major concern, both for the government and the academia.

Several scholars have discussed the economic security dimension of China’s rapid growth. Wang Zhengyi, for one, argued that the evolution of the relationship between economic growth and national security since the opening up of China in 1978 can be divided in two stages. They were first regarded to as two separate logics; however from the mid-1990s on, especially after the Asian financial crisis and China’s accession to the World Trade Organization (WTO), they came to be viewed as constituting one single domain.6 According to Zhenyi, three features of the economic growth in China, i.e. incomplete transformation of the economic structure, increasing dependence on the world economy and intensifying socio- economic polarization, led to this reconceptualization of the linkage between economic growth and security.7 Zhenyi further stated that the economic insecurities resulting from the above mentioned features of Chinese economic growth are:

i) Rising unemployment;

ii) Severe economic disparities between coastal and interior regions, as well as between urban and rural areas;

iii) Decentralization of authority in the Chinese economy and society.8

Similarly, in a volume of essays edited by Werner Draguhn and Robert Ash, the following were addressed as the most crucial determinants of China’s economic insecurity: regional disparities, rural-urban migration, unemployment, food supply, energy supply and environmental protection.9

Another scholar from China, Jiang Yong, evaluated economic security in the Chinese context as “the ability to provide a steady increase in the standard of living for the whole population through national economic development while maintaining economic independence.”10 Accordingly, in order to ensure economic security, China should adopt a policy of “balanced opening”, i.e. while increasing its competitiveness, it should also safeguard the independence of sovereignty over the economy, particularly against foreign capital.11

A remarkable point related to the literature on Chinese economic security is that a significant portion of it is dealing empirically with what Vincent Cable labeled as “security of supply”.12 Economic interdependence is inescapable in the era of globalization, and depending on other countries for means of supply. Cable saw two separate problems here: First, interruptions in import supply can severely disrupt the national economy, and second, overseas suppliers can acquire a monopoly position turning the terms of trade against the importer. Cable argues that these two arguments usually went together, and they were especially evident in the areas of food, strategic minerals (those used in industries regarded as strategic such as aircraft manufacture), energy (esp. oil and gas) and advanced technology.13 In China’s case, since its rapid growth requires a constant supply of raw materials of which the prices are on the rise in the world markets, security of supply and especially the security of energy supply began to top the agenda. For instance, Linda Jakobson and Zha Daojiong, in their study of the motivations behind China’s pursuit of offshore oil supplies, defined the concept of security of supply as the “availability of oil, reliability in delivery and reasonability in prices.”14 The authors suggested that under current circumstances, it would be in the interest of China as well as the established economies to collaborate with rather than confront each other in shaping a new global structure for oil trade.15 Within this framework of collaboration in oil trade, one of the most important aspects is the pipeline transportation, which was examined in the Chinese context by Pak K. Lee, who drew a rather pessimistic picture arguing that possibilities of bilateral or multilateral energy cooperation were rather remote.16

In sum, it can be argued that for China and its rapidly growing economy, economic security means sustaining its growth rate, welfare, and economic power. This is to be achieved by ensuring access to export markets, securing sources of raw materials, especially strategic minerals and hydrocarbons, keeping the import routes open, and preserving macroeconomic stability. The question is then to what extent Xinjiang contributes to this picture, however, before dealing with this question this region’s economic development needs to be evaluated within a historical perspective.

2. Economic Development of Xinjiang in Historical Context

Throughout history, Xinjiang’s economic development has been shaped by a strong confluence of environmental and socio-political factors.17 On the environmental side, the remote and land-locked position of Xinjiang and its inhospitable environmental features emerged as significant obstacles against the economic development of the region.18 However, offsetting these disadvantages, the region is rich in natural resources, including hydrocarbons. The socio-political side, on the other hand, is more complex, and it is related to the complex ethnic composition of Xinjiang. The single largest ethnic group in Xinjiang is the Uyghurs whereas other major non-Han ethnic groups include the Kazakhs, Kyrgyz, Uzbeks and Tajiks, all of whom have kinsmen in the neighboring Central Asian republics of the former Soviet Union.19 As a matter of fact, economic development of Xinjiang cannot be evaluated separately from the ethnic issues involved.

The discussion of economic development in Xinjiang should begin with the Qing Dynasty period. After incorporating Xinjiang as a province into the Chinese empire in 1884, the Qing Dynasty embarked upon an aggressive program of economic development. Agriculture began to be commercialized with a significant expansion of cultivation throughout the region, and there was also progress in other areas of the economy, such as the rise of handicrafts, coal and oil extraction (with Russian assistance) and flourishing foreign trade, which also benefited from the British-Russian imperial rivalry in Central Asia.

The political and social turmoil that followed the collapse of the Qing Dynasty in 1911 negatively influenced the economy of Xinjiang. Carla Wiemer distinguishes four different periods of volatility associated with four consecutive warlords who governed Xinjiang during the republican era. Accordingly, the reign of Yang Zengxin (1911-1928) was a period of “healthy recovery” during which agricultural development was prioritized and Xinjiang exported agricultural commodities in return for imports of industrial products. This was followed by the reign of Jin Shuren (1928-1933) marked by corruption and economic slowdown. Sheng Shicai (1933-1942) brought back recovery to the economy of Xinjiang through liberal reforms and the assistance of the Soviet Union, which was particularly crucial in the revival of extractive industries. The period after Shicai, under the leadership of Zhang Zhizong (1942-1949), was influenced by the civil war and the world war in China, as well as by souring of relations with the Soviet Union, resulting in an economic decline.20

In the 1940s, Uyghurs and other non-Han Chinese in certain parts of Xinjiang experienced a brief period of independence. In what the Chinese official histories call “Three Districts Revolution”, as an uprising against the nationalist central government, the Eastern Turkistan Republic was founded in 1944 with Soviet backing,.21 However, after the People’s Republic was founded in 1949, Xinjiang had to surrender to the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) and the Eastern Turkistan Republic was absorbed into the communist rule through what Chinese official histories call, the “peaceful liberation”.22

Soon after the establishment of the People’s Republic, the central government in Beijing launched two initiatives to consolidate its control over the economy of Xinjiang. The first was the settlement of Han Chinese to the region in order to strengthen the links between the region and the central government. This was important, because the Muslim Uyghur population’s loyalty to the new regime in Beijing was highly suspicious since they were neither pro-Chinese nor pro- Communist.23 Whereas in 1952 only 7.1% of Xinjiang’s population were Han Chinese, this ratio rose to 40.1% as of 1971 and remained almost unchanged ever since. Second was the establishment of the centrally managed Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps. This enterprise was composed of demobilized PLA soldiers, and had a significant economic presence in several fields, such as agriculture, steel, minerals, electricity, water, education, etc. Its share in Xinjiang’s GDP reached a peak level of 31.3% in 1971, later gradually fading down to 16.6% as of 2000.24

The Great Leap Forward and Cultural Revolution periods under Mao Zedong were marked by what Michael Clarke called a “contradiction created by the policy directives from Beijing and what was actually practicable in Xinjiang’s conditions”.25 Policies were implemented and targets were set without regard for the local conditions of Xinjiang and they were characterized by ideological influence that took mainly anti-Islam and anti-Soviet forms in Xinjiang. There was, however, some economic progress, albeit limited. In 1977, Jack Chen argued that China was industrializing without an exodus from the farms to big cities. He compared the rural population ratio of 87% in the unindustrialized China of 1949 with 80% in 1977. Chen was also pointing of a modernization of the economy, stating that the share of modern industry in the total value of industrial production in Xinjiang had risen from 2.9% in 1949 to 78% in 1977.26 As Chen was writing these lines, Deng Xiaoping rose as the leader of the post-Mao China, bringing greater liberalization to Xinjiang. What was remarkable in this period was China embarked on a series of market-oriented economic reforms within the framework of what is called the “socialist market economy”, a system where the state owns a large part of the economy and at the same time allows all entities to participate within a market economy.

At the outset of the reforms, Chinese authorities in Beijing concentrated on the development of the eastern parts of the country, hoping that the positive effects of the development would spill over to the rest of China. However, this plan turned out to be miscalculated, and the outcome was a rapid widening of regional disparities, with the western part of the country significantly remaining behind the eastern belt, and, in contrast with what Chen had written, a massive exodus occurring from rural China to metropolitan areas.27

The central government’s response to the growing disparities during the 1990s took the form of “preferential policies”, a series of privileges and incentives provided for western regions, such as economic zones and tax-sharing arrangements. However, while doing this, Beijing has also recentralized fiscal and decision making powers, keeping much of Xinjiang’s economy under the control of the state.28 There were disparities not only between Xinjiang (or the western part of China in general) and the coastal belt of the country, but also within Xinjiang itself, since the government was investing more in the northern part of Xinjiang, which was heavily colonized by Han Chinese. This was a major reason behind the rise of ethnic minority opposition to Chinese control of Xinjiang and unrest in the region during the 1990s.29

It has also to be remarked that during the 1990s, the central government’s economic strategy for Xinjiang was based on two pillars, “one black, one white”, referring to the priority given to oil extraction and cotton cultivation. While oil was seen as an important source of revenue for the region, the ultimate justification of the emphasis on cotton was the opening up of new land through reclamation, a key element in bringing in large numbers of Han settlers.30 Beijing’s overriding aim in Xinjiang during the decade was to integrate Xinjiang to the rest of China, and this was to be achieved not only by speeding up Han migration, but also by developing communication links, reinforcing military presence in Xinjiang and neutralizing the impact of the neighboring Central Asian states.31

The latter element deserves greater attention here. It was not Deng’s reforms per se that triggered Xinjiang’s opening up to the rest of the world in the economic and commercial sense, but rather the fact these reforms coincided with the breakup of the Soviet Union in 1991 and the resulting emergence of independent Central Asian republics neighboring Xinjiang. This opening up brought risks and benefits at the same time. There were risks, because Beijing feared that these republics, whose people share a common heritage and same ethnic roots with the non-Han in Xinjiang, would support the then emerging reassertions of the ethnic minority opposition to Chinese rule within the region. On the other hand, there were the economic prospects as well. Already before the Soviet collapse, Deng had initiated the “double opening” policy, implying the simultaneous orientation of the region’s economy towards both China and the then Soviet Central Asia.32

After 1991, liberalization of China’s foreign trade regime that coincided with the independence of the Central Asian republics led to a rapid growth in trade between China and Central Asia. This growth was not limited to the bilateral state level, but there was also growth in local trade between Xinjiang and the Central Asian republics in the form of border trade, border residents markets and tourist purchases.33 In sum, China’s strategy was to establish a buffer, while at the same time to benefit from larger amounts of cross border commerce.

As the 1990s were coming to a close, regional income disparities that arose as a result of China’s uneven growth remained a concern for the Beijing government. The most profound policy response came in the form of the “Great Western Development Strategy” launched in January 2000 as an attempt to alleviate the obstacles to development in the western regions of China34, by channeling China’s government spending from the coastal provinces to the west. The strategy focused on the following areas:

- Infrastructure development (focusing on expanding the highway network and building more railway tracks, airports, gas pipelines, power grids, telecommunications networks).

- Environment (projects to protect natural forests along the upper Yangtze River and the upper and middle reaches of the Yellow River).

- Local industry (encouraging different regions to develop industries that maximize local comparative advantages in geography, climate, resources and other conditions; capitalizing on high-tech industries).

- Investment environment (taking steps to attract more foreign investment, capital, technology and managerial expertise by improving industrial structure and reforming state-owned enterprises).

- Science, technology and education.35

Within the framework of this strategy, cumulative fixed investments in Xinjiang totaled 1.4 trillion yuan36 over the period between 2000 and 2009, more than 80% of which coming from the central government.37 During this period, Xinjiang received four times as much investment as it had during the 1990’s, and investments were mainly made in infrastructure projects in agriculture, forestry, energy and transportation sectors.

Recently the central government has adopted the idea of focusing on Xinjiang’s development in order to deepen the Great Western Development Strategy. This approach was explicitly declared when, on 17-19 May 2010, the government held a central work conference on Xinjiang’s development, the first of its kind in the history of the People’s Republic. At this conference, President Hu Jintao announced the goals of the new approach, which are establishing a basic public health system by 2012; leveling the region’s per capita income with the Chinese average by 2015; and eliminating absolute poverty and achieving a “moderately prosperous” society by 2020. In order to attain these goals, fixed assets investment in Xinjiang over the period 2011-2015 will double that of the previous five-year period, income tax levels will be reduced, undeveloped land will be made available for construction, and access requirements to industries related to resources and/or those with high market demand will be relaxed.38

Although the central government is heavily funding the Great Western Development Strategy, and several important projects have already been brought to life in the region, there are two crucial points that have to be made. First, the western regions of China (including Xinjiang) exhibit a great diversity in terms of ethnic composition and despite denials by the Chinese government, there is an almost consensus among scholars that the Great Western Development Strategy is aimed at increasing material wealth of the people in order to ensure greater minority cooperation, which would lead to their integration with the Han Chinese and help silence the separatist movements. As Michael Clarke argues, the Great Western Development Strategy suggested that “while the state continues to stress the need to address the problems of uneven development in ethnic minority regions, it nonetheless maintains that this will be done on the basis of preserving ‘national unity’ and ‘social stability’ with the dominant ethnic group –the Han– as the leading agents of modernization”.39 Second, there is another influential opinion among scholars that the richer eastern parts of China are benefiting more from the Great Western Development Strategy than the western regions, because this strategy focuses on infrastructure, energy and natural resource extraction, instead of directly addressing the social issues in the western regions. It is argued that the western regions would have benefited more if the campaign had focused more on poverty relief, improvement in education and health care.40

Despite its problems and setbacks, Xinjiang is currently on a development path. The next section of the article will examine what this development means for China’s economic security.

3. The Role of Xinjiang in China’s Economic Security

Given its radical transformation and rapid growth rate, China is obliged to take the necessary measures to deal with collateral macroeconomic disturbances (such as unemployment, income equality, etc), and to ensure its continued access to world markets where it can sell its products. Since it relies to a great extent on imports of raw materials to fuel its economic growth, China has to ensure continued inflow of such supplies as well, while at the same time maintaining its economic independence, which is achieved by avoiding excessive reliance on a single source of imports and diversifying the sources instead. In this part of the article, we will discuss to what extent Xinjiang contributes to China’s economic security in the each of the areas mentioned above.

3.1. Macroeconomic Indicators

Macroeconomic disturbances threaten a country’s economic security. In China’s case, such disturbances emerge as a result of the country’s rapid growth and transformation, and appear in the form of rising unemployment; severe economic disparities between coastal and interior regions, as well as between urban and rural areas; and decentralization of authority in the Chinese economy and society. In order to deal with these insecurities, China has embarked on a series of adjustments since the mid-1990s, especially gradual institutional adjustments, establishing a social security system and coordinating the development of the regional economy.41

Xinjiang remains far behind the eastern provinces of China in terms of average incomes. In 2009, when Chinese GDP grew by 8.7% and most central and western provinces of the country achieved double-digit growth rates thanks to the stimulus package launched by the government as a measure against the effects of the global crisis, Xinjiang’s GDP rose by only 8.1%.

During the same year, average annual disposable income was 12,258 yuan for urban households, and 4,005 yuan for rural households in Xinjiang.42 Both figures were below the national averages, which are 17,175 yuan and 5,153 yuan, for urban and rural households respectively However, it has to be noted that the income gap between Xinjiang and the rest of China has begun to narrow, mainly because of rising employment in the region. Until 2008, Xinjiang’s employment rate was increasing slower than the China average. In 2009, however, total employment rose by 0.7% in China, whereas the increase in Xinjiang was 2.3%.43

On the negative side, however, inflation is rising faster in Xinjiang compared to the rest of China. In August 2010, while the consumer price index (CPI) increased by 2.8% on a year-on-year basis in China, this increase was 3.8% in Xinjiang, which is influenced by high levels of rural inflation.44

In sum, from a macroeconomic perspective, Xinjiang has a negative yet improving position as far as China’s economic security is concerned. Its economic backwardness relative to the more developed provinces can be regarded as major concern, whereas unemployment and rising inflation continue to pose a problem.

3.2. Security of Supply

Economic interdependence means that all countries are dependent on others to some extent for one kind of supplies or another. This implies that interruptions in imports of the supply can severely disrupt the national economy and also overseas suppliers can acquire a monopoly position turning the terms of trade against the importer. Vincent Cable argues that these two arguments usually go together and they are especially evident in the areas of food, strategic minerals (those used in industries regarded strategic such as aircraft production), energy (esp. oil and gas) and advanced technology.45 Food supply and energy supply are often defined as the most crucial determinants of China’s economic security, together with the macroeconomic disturbances discussed above. As the economy of China grows, so does its need for supplies of raw materials and resources, and security of supply becomes an increasing concern for the decision makers in Beijing. This part of the article will start with two areas of supply security, namely energy security and food security, the first associated with the needs of a growing economy and the latter with the needs of a growing population. Additionally, a third area will be discussed, which is of vital importance for China’s textile industry, namely cotton.

Energy. Due to the high rate of economic growth in China, demand for energy outstrips local supply and there is an increasing reliance on imports, although China is the world’s fifth largest oil producer with a production volume of 189 million tons in 2009.46 After 1978, as the oil consumption of the major economic powerhouses in the world (United States, Europe and Japan) almost remained constant, China’s consumption nearly quadrupled.

Dependence on imports is by itself an economic security concern, which is further heightened by the volatilities in global energy markets and political instability in the world’s energy producing regions. China is currently dependent on imported oil. Until 1993, it had been self-sufficient in this respect, even producing a surplus. However, after this year consumption increased faster than local production and the resulting gap is widening every year. The local production/consumption ratio, which was 120.8% in 1992, declined below the self- sufficiency line in 1993 with 98.8% and continued to decrease, to 72.7% in 2000 and to 46.7% in 2009.47 This means that today China is producing less than half of the oil it consumes and for the rest it depends on imports.48 As this ratio falls, imports increase (in 2009, China’s imports of crude oil rose by 13.8%), and so do the economic security concerns.

China’s approach to energy security is “evolving from a vision of tight government control and self-reliance to a more liberal outlook that accepts market forces and diversified energy types and sources”.49 Within this framework, China is establishing energy supply relations with countries all around the world. In 2009, the Middle East supplied 50.7% of China’s total oil imports, Africa 20.5%, Southeast Asia 13.5% and Russia 13.1%.50 Furthermore, in another attempt to ensure its economic security, China is purchasing stakes in foreign oil companies. For instance, the acquisition of PetroKazakhstan by China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC), in October 2005 is considered a landmark in China’s overseas oil development.51

There is, however, a different picture as far as other energy sources, i.e. natural gas and coal, are concerned. China consumes gas and coal as much as it produces them, not more. In other words, China is self-sufficient in gas and coal.

As a region within China, Xinjiang’s contribution to the country’s energy supply security takes two forms; first as a producer of energy resources, and second as a transit route of energy resources imported from abroad.

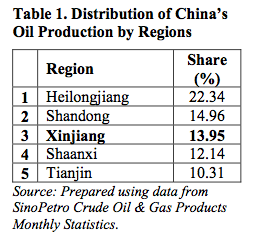

Xinjiang is a part of China’s quest to diversify its oil resources and this can be traced back to 1991 when the Chinese government granted the development rights of the Tarim Basin to Japan National Oil Corporation. Following this initial opening, Xinjiang’s oil output gradually increased. In 2009, Xinjiang produced 25.1 million tons of crude oil52, and, as seen in Table 1, Xinjiang is the third largest oil-producing region in the country. Yet the region can be expected to climb to higher ranks in the near future. Only 33% of China’s oil reserves are estimated to have been discovered so far and Xinjiang hosts large amounts of undiscovered oil reserves, particularly in Tarim Basin53, which is estimated to contain 10 billion tons of oil. CNPC is known to have plans to develop Xinjiang as a major oil and production center. Having invested over 300 billion yuan in the region so far, the company aims to increase annual production to 50 million tons by 2015, and to 60 million tons by 2020.54

Xinjiang has a key position in China’s oil supply security, not only because it is the third largest producer of oil among China’s provinces, but also because it functions as a transit route. Due to its strategic concerns over relying too heavily on maritime imports of oil, China has a significant interest in securing oil supplies through pipelines from Central Asia. Since Xinjiang is the only region in China that is neighboring the Central Asian republics, Central Asian oil (and a large proportion of Russian oil) has to enter the Chinese pipeline network from Xinjiang. The first transnational oil pipeline built for this purpose was that of the Sino-Kazakh Oil Pipeline Co. Ltd.55 which began pumping oil in July 2006. This pipeline starts in Atasu in northwestern Kazakhstan, enters Xinjiang territory at Alashankou on the Kazakh-Chinese border, and terminates at PetroChina Dushanzi Petrochemical Company. Half of the oil transported through this pipeline is Kazakh oil and the other half is Russian oil. When this pipeline reaches its full capacity of 20 million tones per year, it will account for around 15% of China’s oil imports. In the mean time, the oil extracted in or imported through Xinjiang is distributed to the rest of China through the Urumqi-Lanzhou oil product pipeline and the Shanshan-Lanzhou crude oil pipeline.

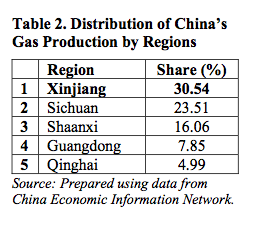

As far as the supplies of natural gas are concerned, Xinjiang is singled out as the largest producer region in China (see Table 2). Xinjiang’s gas output has been growing rapidly since the West-East Gas Pipeline started operation in December 2004. In 2005, the region produced 10.6 billion cubic meters of gas, and this figure rose to 24.5 billion cubic meters in 2009.56 According to the calculations of CNPC, Xinjiang holds 490 billion cubic meters of proven gas reserves, about 20% of the Chinese total.57

As far as the supplies of natural gas are concerned, Xinjiang is singled out as the largest producer region in China (see Table 2). Xinjiang’s gas output has been growing rapidly since the West-East Gas Pipeline started operation in December 2004. In 2005, the region produced 10.6 billion cubic meters of gas, and this figure rose to 24.5 billion cubic meters in 2009.56 According to the calculations of CNPC, Xinjiang holds 490 billion cubic meters of proven gas reserves, about 20% of the Chinese total.57

Although China is to a great extent self-sufficient in terms of natural gas, the government is planning to import Central Asian gas in order to ensure long term economic security and meet the rapidly increasing demand for cleaner burning fuel.

To that end, China inked a 30-year deal with Turkmenistan in 2006 for 10 billion cubic meters of gas per year, rising to 30 billion by 2012. The Kazakh part of the pipeline, which will carry the gas coming from Turkmenistan via Uzbekistan will link Shymkent on Uzbek-Kazakh border to Khorgos in Xinjiang, and will have a capacity of 40 billion cubic meters per year.

To that end, China inked a 30-year deal with Turkmenistan in 2006 for 10 billion cubic meters of gas per year, rising to 30 billion by 2012. The Kazakh part of the pipeline, which will carry the gas coming from Turkmenistan via Uzbekistan will link Shymkent on Uzbek-Kazakh border to Khorgos in Xinjiang, and will have a capacity of 40 billion cubic meters per year.

The gas arriving in Xinjiang will be distributed to the rest of China through the 4,200-kilometer West-East Pipeline linking Xinjiang to Shanghai in the east and a second line of 4,843 kilometers that connects Xinjiang with Guangzhou in the southeast.

Gas is important for China’s economic security, because abundant supplies of natural gas will help to overcome China’s dependence on coal. Coal is a basic energy source in China making up 70% of the country’s total primary energy consumption,58 and as discussed above, China is self-sufficient in terms of coal supplies. China is the largest coal producer in the world, with a share of 45.6% in the world’s total production as of 2009, and at the same also the largest consumer, with 46.9%.59 In other words, almost the half of the world’s coal is produced and consumed in China.

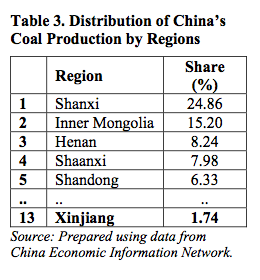

Although Xinjiang is not one of the major coal producing regions in China (see Table 3), it is rapidly growing its coal industry and making preparations for exploration of large- scaled coalmines.

Currently, coal resources already utilized only account for 13% of total deposits. An important portion of the unutilized resources is to be found in Xinjiang.

Currently, coal resources already utilized only account for 13% of total deposits. An important portion of the unutilized resources is to be found in Xinjiang.

Whereas Xinjiang’s annual coal output amounts for the time being to around 50 million tons, the region’s coal production is expected to rise to 1 billion tones and account for more than 20% of the total output in China until 2020.60

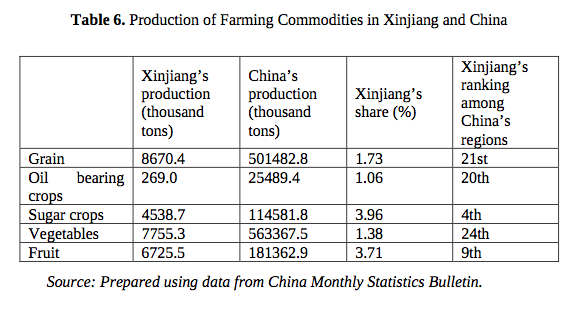

Food. Food security should be dealt with within the larger framework of agriculture in Xinjiang. Stockbreeding and pastoralism dominate the region’s economy, however it is not possible to argue that agriculture is well developed in Xinjiang, mainly due to climatic and geographical problems.

There are severe irrigation problems in grasslands and deserts, as well as occasional droughts, which seriously undermine the agricultural output.

As a result, although its economy is dominated by agriculture, Xinjiang is not one of the leading producers in China, and therefore its contribution to China’s food security is minimal.

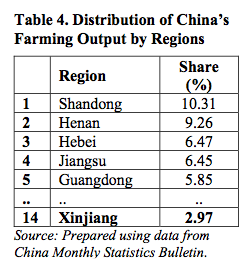

In 2007, the total value of China’s farming output was 2.15 trillion yuan, whereas Xinjiang share in this was 2.97% with 63.9 billion yuan.

In 2007, the total value of China’s farming output was 2.15 trillion yuan, whereas Xinjiang share in this was 2.97% with 63.9 billion yuan.

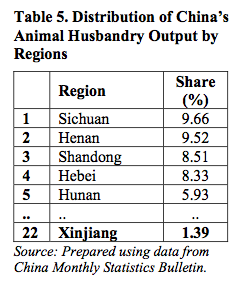

Similarly, in China’s total animal husbandry output value of 1.36 trillion yuan, Xinjiang’s share was only 1.39% with 18.9 billion yuan (See Tables 4 and 5).

Fruit, especially melons and grapes, are often regarded as the most important farming product in Xinjiang.

A closer look at production levels of various farming products reveals that although this is true, Xinjiang is still not one of the major producers of fruit in China.

The data in Table 6 suggests that Xinjiang’s share in China’s production of farming commodities exceeded 3% only in fruit and sugar crops.

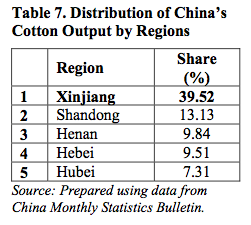

Cotton. Another agricultural product, which is not related to food security but still important in terms of China’s security of supply, is cotton.

The textile industry is one of the major engines of China’s export growth and until recently it has been growing at a rate that exceeded the overall economic growth of China. The recent global economic downturn has negatively affected the Chinese textile industry and in 2009, and the industry experienced its largest decline in exports volume over the past three decades.61 Despite this drawback, China’s textile industry continues to increase its output. In 2009, China produced about 24 million tons of yarn, an increase of 12.7% year on year, and the amount of clothes produced was up from 6.9% to 23.75 billion units.62

China’s competitiveness in the textile industry is derived from its low cost base. While labor costs are crucial in this respect, there is also the need for low-cost raw materials, in this case cotton. As discussed earlier, cotton is one of the two pillars on which the Xinjiang economy is based. Indeed, Xinjiang is the leading cotton producer in China on a regional basis, accounting to around 40% of the total output (see Table 7). In 2009, the region produced 2.5 million tons of cotton, ensuring the supply security of China’s rapidly growing textile industry.

3.3. Access to Markets

In an age of growing economic interdependence, security in the economic realm is ensured not only by securing the supplies to be used for production, but also by ensuring access to markets where the output is to be sold. Export growth is an important engine of economic growth and increasing the exports requires access to markets in a sustainable manner. In our case, China can be said to capitalize on a significant level of market access and therefore economic security. This argument is supported by the fact that China’s export growth goes parallel to the growth in output, meaning that as China produces more, it also exports more, because it has sufficient access to markets. Moreover, China’s market access was consolidated after it joined the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001, which eliminated certain barriers to trade for China.

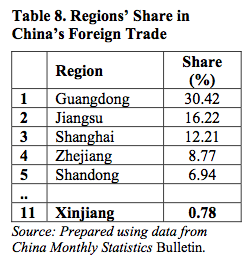

Market access can take two forms. The first is related to the level of trade barriers such as quotas and tariffs a country is facing. The second form is the physical one, which refers to logistical and geographical issues. Since the unit of analysis of this article is the regional level, this section will be only dealing with the latter, by analyzing Xinjiang’s place in China’s foreign trade, both in terms of volume and logistics.

Xinjiang has only a minimal share in China’s total foreign trade. In 2009, while China’s foreign trade totaled US$ 2.21 trillion (exports US$ 1.20 trillion, imports US$ 1.01 trillion), Xinjiang’s foreign trade volume was only US$ 13.8 billion (exports US$ 10.8 billion, imports US$ 3.0 billion). This is not surprising, because, as seen in Table 8, coastal provinces of China are accounting for the bulk of China’s foreign trade.63 However, two points should be made here. First, Xinjiang has by far the largest foreign trade volume among the western provinces of China (almost 50 times greater than Tibet’s trading volume).

Second, and more importantly, until the recent global economic crisis, Xinjiang has been rapidly increasing its foreign trade volume. Xinjiang’s foreign trade expanded by 50.7% in 2007 and by a massive 62% in 2008, before declining by 37.8% in 2009.64 A rapid recovery is on the way in Xinjiang, and it is safe to argue that Xinjiang is increasingly getting more assertive in foreign trade.

This increasing role of Xinjiang within China’s foreign trade is a result of the government’s policies to diversify China’s trading partners and there are several factors behind this. There is the intention to increase cost efficiency. Currently, China executes a substantial portion of its foreign trade through maritime routes.65 Although this is a natural result of China’s geographic position, it also leads to high logistics costs. Chinese logistics costs are already at 18.5% of the GDP, nearly double that of more developed countries, and this is a threat against Chinese exports’ competitiveness.66

Land transportation to and/or through Central Asian republics neighboring Xinjiang offers low-cost trading opportunities and this is why the Chinese government is heavily investing in the linkages between Xinjiang and Central Asian republics with the aim of turning the region into a transport and trading hub. For this purpose, the current railroad network, connecting Xinjiang with Kazakhstan, will be increased from 3,600 kilometers to 12,000 kilometers by 2020, with the addition of new lines linking Xinjiang with Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, Afghanistan and Pakistan. In addition, 12 new highway projects with a total length of 7,155 kilometers are included in the development plans.67

Greater trade with Central Asian republics brings about significant prospects for China. Trade between China and Central Asian republics has advantages, not only due to geographical proximity, but also due to the common cultural values of Xinjiang and these republics, which make it easier to establish communication, mutual understanding and trust, as well as the complementary nature of the economies of Xinjiang and Central Asian republics.68 In the meantime, trade opportunities are not limited to bilateral trade with Central Asian republics, but also include trade with Europe. Railway transportation through Xinjiang and Central Asia to Europe is a cost-efficient alternative for maritime transportation, which halves current traveling time.69 In sum, Xinjiang is on its way to become China’s gateway opening to the west, first to Central Asia and then to Europe. Railways, highways, pipelines and trade routes are passing through Xinjiang and connecting China to the rest of the world in a more time and cost efficient manner

than the traditional maritime routes departing from the country’s east coast.

CONCLUSION

The empirical evidence analyzed in this paper suggests that Xinjiang is playing a vital and strategic role in China’s economic security, because:

It is the single largest contributor to China’s self-sufficiency in natural gas. It is also a major domestic producer of oil, while production of coal is expected to increase drastically in a decade. Furthermore, it is the transit route of energy resources imported from abroad, which will play an increasingly crucial role in China’s supply security.

As China’s gateway to Central Asia and beyond, its strategic importance vis-à- vis China’s foreign trade is rising. It is becoming the largest hub for foreign trade with reduced logistics costs. It is the single largest raw material supplier of China’s booming textile industry.

Although Xinjiang is behind most of the rest of China in terms of its share from the national income (and likely to remain so for years to come) the rest of China owes a great deal for its economic growth to Xinjiang. Apparently, Xinjiang’s economic structure fits the picture of the periphery, of which the main function is to provide the core with energy supplies and raw materials. This is precisely why the Chinese government focuses on the economic development of the region. A developed and stable Xinjiang is one of the keys of ensuring China’s economic security in the long term. Beijing cannot take the risk of instability in a region, which produces its energy supplies and cotton, serves as a major foreign trade hub, and hosts important transportation routes connecting China with the rest of the world are passing.

Beijing’s reliance on economic development as a strategy to deal with ethnic problems cannot be denied. However, the ethnic issue is rapidly becoming a sub- component of the economic security issue in this high-growth opening-up era of the Chinese economy. In other words, Beijing wants ethnic stability in Xinjiang not only for political reasons, but mainly for a stable, and problem-free Xinjiang that is required for China’s economic security. As economic pragmatism undermines all kinds of political ideologies in today’s globalizing world, ethnic issues such as those in Xinjiang cannot be understood without incorporating the matter of economy in the larger picture.

About the author:

*Altay Atli, PhD Candidate, Boğaziçi University, Department of Political Science and International Relations. E- mail: [email protected]..

Source:

This article was published by JTW, OAKA, Cilt: 6, Sayı: 11, ss. 111-133, 2011

References:

Becquelin, Nicolas, “Xinjiang in the Nineties”, The China Journal, No. 44, 2000.

Buzan, Barry, “New Patterns of Global Security in the Twenty-First Century”, International Affairs, Vol. 67, No. 3, 1991.

Cable, Vincent, “What is International Economic Security?”, International Affairs, Vol. 71, No. 2, 1995.

Chan, Kam-Wing, “Internal Labor Migration in China: Trends, Geographical Distribution and Policies”, United Nations Expert Group Meeting on Population Distribution, Urbanization, Internal Migration and Development Conference Proceedings, 2008.

Chen, Jack, The Sinkiang Story, (New York: Macmillan Publishing Co Inc, 1977).

Christofferson, Gaye, “Xinjiang and the Great Islamic Circle: the Impact of Transnational Forces on Chinese Regional Economic Planning”, China Quarterly, No. 133, 1993.

Clarke, Michael, “Xinjiang and China’s Relations with Central Asia, 1991-2001: Across the ‘Domestic-Foreign Frontier’?”, Asian Ethnicity, Vol. 4, No. 2, 2003.

Clarke, Michael, “China’s Internal Security Dilemma and the ‘Great Western Development’: The Dynamics of Integration, Ethnic Nationalism and Terrorism in Xinjiang”, Asian Studies Review, Vol. 31, No. 3, 2007.

Cutler, Robert M., “Xinjiang – China’s Energy Gateway”, Asia Times Online, 10 July 2009, (http://www.atimes.com/atimes/China_Business/KG10Cb01.html).

Dillon, Michael, Xinjiang: China’s Muslim Far Northwest, (London: Routledge, 2004).

Draguhn, Werner and Ash, Robert (Ed.), China’s Economic Security, (Richmond, Surrey: Curzon Press, 1999).

Dreyer, June Teufel, “The Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region at Thirty: A Report Card”, Asian Survey, Vol. 26, No. 7, 1981.

Gosset, David, “The Xinjiang Factor in the New Silk Road”, Asia Times Online, 22 May 2007, (www.atimes.com/atimes/Central_Asia/IE22Ag01.html).

Jakobson, Linda & Zha, Daojiong, “China and the Worldwide Search for Oil Security”, Asia-Pacific Review, Vol. 13, No. 2, 2006.

Jiang, Yong, “Economic Security: Redressing Imbalance”, China Security, Vol. 3, No. 2, 2007.

Lee, Pak K., “China’s Quest for Oil Security: Oil (Wars) in the Pipeline?”, The Pacific Review, Vol. 18, No. 2, 2005.

Liu, Qingjian, “Sino-Central Asian Trade and Economic Relations: Progress, Problems and Prospects”, Ethnic Challenges beyond Borders: Chinese and Russian Perspectives of the Central Asian Conundrum, Zhang Yongjin &

Rouben Azizian (Ed.), (London: MacMillan Press Ltd., 1998).

Rui, Xia, “Asphalt Net Covers China’s West”, Asia Times Online, 15 September 2005, (http://www.atimes.com/atimes/China_Business/GI15Cb01.html).

Wan, Zhigong, “CNPC has Huge Plans for Xinjiang”, China Daily Online, 20 July 2010, (http://english.peopledaily.com.cn/90001/90778/90862/7072547.html).

Wang, Zhengyi, “Conceptualizing Economic Security and Governance: China Confronts Globalization”, The Pacific Review, Vol. 17, No. 4, 2004.

Wiemer, Carla, “The Economy of Xinjiang”, Xinjiang: China’s Muslim Borderland, edited by S. Frederick Starr, (Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe Inc., 2004).

Yu, Shujun, “Blueprint for a Properous Xinjiang”, Beijing Review, No. 23, 10 June 2010.

“BP Statistical Review of World Energy”, June 2010.

“China Builds New Silk Roads to Revive Fortunes of Xinjiang”, Xinhua News Agency, 2 July 2010, (http://news.xinhuanet.com/english2010/china/2010- 07/02/c_13380771_2.htm).

“China Economic Information Network” bulletin, various issues.

“China Energy: Petroleum Demand”, EIU Industry Wire, 7 February 2008. “China Monthly Statistics” bulletin, various issues.

“China’s Textile Industry Output Rises 10%”, China Daily Online, 3 February 2010, (http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/business/2010-02/03/content_942 3379.htm).

“China’s Xinjiang Coal Reserves Adds 18.98 Billion Tons”, China Mining Federation, 8 May 2008, (http://www.chinamining.org/News/2008-05- 08/1210233199d13585.html).

“China’s Thirst for Oil”. ICG Asia Report No.153, 9 June 2008.

“Country Profile China”, Economist Intelligence Unit, London, 2009.

“Deutsche Bahn stoppt Güterzug-Verbindung nach China”, Verkehrsrundschau, 25 June 2009, (http://www.verkehrsrundschau.de/deutsche-bahn-stoppt-gueterzug- verbindung-nach-china-852879.html).

“Gediqu chengzhen touzi qingkuang (2010 nian 1-8 yue)”, China National Bureau of Statistics, (http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/jdsj/t20100921_402673820.htm).

“Gediqu jumin xiaofei jiage zhishu (2010 nian 8 yue)”, China National Bureau of Statistics, (http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/jdsj/t20100919_402673826.htm).

“Güterzüge nach China”, N-Tv Online, 20 September 2008, (http://www.n- tv.de/wirtschaft/meldungen/Gueterzuege-nach-China-article24327.html)

“Quanguo niandu tongji gongbao – Xinjiang (2009 nian)”, China National Bureau of Statistics, (http://www.stats.gov.cn/was40/gjtjj_detail.jsp?channelid=4 362&record=7).

“Rising Logistics Costs Threaten Chinese Competitiveness”, CER-China Logistics News, 30 April 2008.

“SinoPetro Crude Oil & Gas Products Monthly Statistics” bulletin, various issues.

“Textile, Garment Exports to Suffer Largest Drop in 30 Years”, China Daily Online, 21 October 2009, (http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/business/2009- 10/21/content_8827056.htm).

“Xinjiang Development at the New Starting Point”, People’s Daily Online, 7 July, 2010, (http://english.peopledaily.com.cn/90001/90780/91342/7055962.html).

Notes:

1. In this article, the term “China” refers to the People’s Republic of China.

2. David Gosset, “The Xinjiang Factor in the New Silk Road”, Asia Times Online, 22 May 2007, (www.atimes.com/atimes/Central_Asia/IE22Ag01.html).

3. For instance, as of August 2010, the cumulative amount of investment channeled by the central

government to Xinjiang was 7.4 times larger than the investment stock in Tibet Autonomous Region. “Gediqu chengzhen touzi qingkuang (2010 nian 1-8 yue)”, China National Bureau of Statistics, (http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/jdsj/t20100921_402673820.htm).

4. Barry Buzan, “New Patterns of Global Security in the Twenty-First Century”, International Affairs, Vol. 67, No. 3, 1991, pp. 431-451.

5. Ibid, p. 445.

6. Wang Zhenyi, “Conceptualizing Economic Security and Governance: China Confronts

Globalization”, The Pacific Review, Vol. 17, No. 4, 2004, p. 524.

7. Ibid, pp. 527-8.

8. Ibid, p. 529.

9. Werner Draguhn & Robert Ash (Ed.), China’s Economic Security, (Richmond, Surrey: Curzon

Press, 1999).

10. Jiang Yong, “Economic Security: Redressing Imbalance”, China Security, Vol. 3, No. 2, 2007, p.

66.

11. Ibid, p. 76.

12. Vincent Cable, “What is International Economic Security?”, International Affairs, Vol. 71, No. 2,

1995, pp. 305-324.

13. Ibid, pp. 313-319.

14. Linda Jakobson and Zha Daojiong, “China and the Worldwide Search for Oil Security”, Asia-Pacific

Review, Vol. 13, No. 2, 2006, p. 62.

15. Ibid, pp. 68-70.

16. Pak K. Lee, “China’s Quest for Oil Security: Oil (Wars) in the Pipeline?”, The Pacific Review, Vol. 18, No. 2, 2005, p. 289.

17. Carla Wiemer, “The Economy of Xinjiang”, S. Frederick Starr (Ed.), Xinjiang: China’s Muslim Borderland, (Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe Inc., 2004), p.163.

18. Xinjiang lies on the northwestern frontier of China and is divided by the great range of mountains, the Tianshan. The Zhungar Basin lies to the north and the Tarim Basin, which is largely occupied by the Taklamakan Desert, lies to the south.

19. According to the most recent census (2000), major nationalities in Xinjiang are: Uyghur 45%, Han 41%, Kazakh 7%, Hui 5%, Kyrgyz 0.9%, Mongol 0.8%, Dongxiang 0.3%, Tajik 0.2%. At the same census, Han Chinese made up 91.6% of China’s total population. “Country Profile China”, Economist Intelligence Unit, London, 2009, p.15.

20. Carla Wiemer, “The Economy of Xinjiang”, pp. 164-8.

21. This was the Second Eastern Turkistan Republic. The first one was founded in Khotan in November 1933, as a result of the Islamist and nationalist aspirations of the Uyghur people there. However, it lasted only until February 1934 when the city of Kashgar was taken by the warlord Ma Zhongying as a part of his campaign against his rival Sheng Shicai.

22. Michael Dillon, Xinjiang: China’s Muslim Far Northwest, (London: Routledge, 2004), pp.32-6.

23. June Teufel Dreyer, “The Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region at Thirty: A Report Card”, Asian

Survey, Vol. 26, No. 7, 1981, pp. 722–723.

24. Carla Wiemer, “The Economy of Xinjiang”, p. 169.

25. Michael Clarke, “Xinjiang and China’s Relations with Central Asia, 1991-2001: Across the

‘Domestic-Foreign Frontier’?”, Asian Ethnicity, Vol. 4, No. 2, 2003, pp. 207-224.

26. Jack Chen, The Sinkiang Story, (New York: Macmillan Publishing Co Inc, 1977), p. 294.

27. There emerged a “floating population” of migrants from rural areas to cities, of which the number was 40 million in 1985, increasing to 140 million as of 2003. About 20 million people are added to this population every year. Consequently the level of urbanization in China began to increase, from 27% in 1990 to 36% in 2000, and to 43% in 2005. This figure is estimated to rise to 65% by 2020. Kam-Wing Chan, “Internal Labor Migration in China: Trends, Geographical Distribution and Policies”, United Nations Expert Group Meeting on Population Distribution, Urbanization, Internal Migration and Development Conference Proceedings, 2008, p. 93.

28. Nicolas Becquelin, “Xinjiang in the Nineties”, The China Journal, No. 44, 2000, pp. 71-2.

29. Michael Clarke, “Xinjiang and China’s Relations with Central Asia, 1991-2001: Across the

‘Domestic-Foreign Frontier’?”, p. 212.

30. Nicolas Becquelin, “Xinjiang in the Nineties”, p.83.

31. Ibid, p.67.

32. Gaye Christofferson, “Xinjiang and the Great Islamic Circle: the Impact of Transnational Forces on Chinese Regional Economic Planning”, China Quarterly, No. 133, 1993, p. 136.

33. Liu Qingjian, “Sino-Central Asian Trade and Economic Relations: Progress, Problems and Prospects”, Zhang Yongjin and Rouben Azizian (Ed.), Ethnic Challenges Beyond Borders: Chinese and Russian Perspectives of the Central Asian Conundrum, (London: MacMillan Press Ltd., 1998), p. 182.

34. The “western regions” as covered by the plan included six provinces (Gansu, Guizhou, Qinghai, Shaanxi, Sichuan, Yunnan), three autonomous regions (Ningxia, Tibet, Xinjiang), and one municipality (Chongqing).

35. These major objectives of the plan were laid out by Chinese Premier Zhu Rongji at the March 2000 session of the National People’s Congress.

36. In this article, “yuan” denotes the principal unit of renminbi, which is the official currency of China. As of 1 December 2010, one US dollar is equal to 6.68 yuan, and one euro is equal to 8.67 yuan (official rates announced by the Bank of China).

37. “Xinjiang Development at the New Starting Point”, People’s Daily Online, 7 July 2010, (http://english.peopledaily.com.cn/90001/90780/91342/7055962.html).

38. Yu Shujun, “Blueprint for a Properous Xinjiang”, Beijing Review, No. 23, 10 June 2010.

39. Michael Clarke, “China’s Internal Security Dilemma and the ‘Great Western Development’: The Dynamics of Integration, Ethnic Nationalism and Terrorism in Xinjiang”, Asian Studies Review,

Vol. 31, No. 3, 2007, p. 339.

40. Rui Xia, “Asphalt Net Covers China’s West”, Asia Times Online, 15 September 2005, (http://www.atimes.com/atimes/China_Business/GI15Cb01.html).

41. Wang Zhengyi, “Conceptualizing Economic Security and Governance: China Confronts Globalization”, The Pacific Review, Vol. 17, No. 4, 2004, p. 536.

42. “Quanguo niandu tongji gongbao – Xinjiang (2009 nian)”, China National Bureau of Statistics, (http://www.stats.gov.cn/was40/gjtjj_detail.jsp?channelid=4362&record=7).

43. Ibid.

44. “Gediqu jumin xiaofei jiage zhishu (2010 nian 8 yue)”, China National Bureau of Statistics,

(http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/jdsj/t20100919_402673826.htm).

45. Vincent Cable, “What is International Economic Security?”, pp. 313-319.

46. BP Statistical Review of World Energy, June 2010, p .9.

47. Calculated using the data in BP Statistical Review of World Energy, p. 9 and 12.

48. As of 2009, China is the second largest oil importer and consumer in the world after the United States

49. “China’s Thirst for Oil”, ICG Asia Report, No.153, 9 June 2008, p. 4.

50. Calculated using the data in BP Statistical Review of World Energy, p. 21.

51. “China Energy: Petroleum Demand”, EIU Industry Wire, 7 February 2008.

52. China National Bureau of Statistics.

53. Other basins in Xinjiang that contain oil reserves are Junggar and Turpan-Hami basins.

54. Wan Zhigong, “CNPC has Huge Plans for Xinjiang”, China Daily Online, 20 July 2010,

(http://english.peopledaily.com.cn/90001/90778/90862/7072547.html).

55. This company is a 50:50 joint venture between CNPC and Kazakhstan’s KazTransOil.

56. China National Bureau of Statistics.

57. Robert M. Cutler, “Xinjiang – China’s Energy Gateway”, Asia Times Online, 10 July 2009,

(http://www.atimes.com/atimes/China_Business/KG10Cb01.html).

58. “Country Analysis Briefs: China”, U.S. Energy Information Administration, July 2009, (http://www.eia.doe.gov/emeu/cabs/China/Full.html).

59. BP Statistical Yearbook of Energy.

60. “China’s Xinjiang Coal Reserves Adds 18.98 Billion Tons”, China Mining Federation, 8 May 2008, (http://www.chinamining.org/News/2008-05-08/1210233199d13585.html).

61. “Textile, Garment Exports to Suffer Largest Drop in 30 Years”, China Daily Online, 21 October 2009, (http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/business/2009-10/21/content_8827056.htm).

62. “China’s Textile Industry Output Rises 10%”, China Daily Online, 3 February 2010, (http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/business/2010-02/03/content_9423379.htm).

63. In 2007, the eastern part of the country contributed to 91.2% of the total trade volume, where as this figure was 4.89% for central China and 3.94% for western China (Calculated using data from China Monthly Statistics, 3 February 2008).

64. China National Bureau of Statistics.

65. In 2007, 63.9% of China’s foreign trade was transported through waterways, whereas this ratio was 24.4% for railways and 11.6% for highways (Calculated using data from China Monthly Statistics 3 February 2008).

66. “Rising Logistics Costs Threaten Chinese Competitiveness”, CER-China Logistics News, 30 April 2008.

67. “China Builds New Silk Roads to Revive Fortunes of Xinjiang”, Xinhua News Agency, 2 July 2010, (http://news.xinhuanet.com/english2010/china/2010-07/02/c_13380771_2.htm).

68. Liu, 1998, pp. 192-3.

69. On 9 January 2008, China, Mongolia, Russia, Belarus, Poland and Germany signed an agreement,

according to which a scheduled container train (the Trans-Eurasian Express) would be shuttling between China and Germany in a year’s time. In September 2008, the train made its maiden voyage, carrying 50 containers of high-tech products from Xiangtang in China to Hamburg in Germany, a distance of 12,000 kilometers, in 17 days. In comparison, goods delivered by sea from China to Germany need around 35 days to reach their destination. Introduction of regular services by the Trans-Eurasian Express has been postponed by the German side due to the global economic crisis. “Güterzüge nach China”, N-Tv Online, 20 September 2008, (http://www.n- tv.de/wirtschaft/meldungen/Gueterzuege-nach-China-article24327.html); “Deutsche Bahn stoppt Güterzug-Verbindung nach China”, Verkehrsrundschau, 25 June 2009, (http://www.verkehrsrunds chau.de/deutsche-bahn-stoppt-gueterzug-verbindung-nach-china-852879.html).