ASEAN Should Not Fall Into China’s Trap On South China Sea – Analysis

Ministers of the 10-member Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), China and other members of the East Asia Summit (EAS) will gather in Manila this week (Aug. 2-8) to prepare the agenda for the forthcoming 31st ASEAN Summit and its related meetings in November.

This week’s meetings in Manila will be very important for two reasons. First, ASEAN is celebrating its 50th anniversary on Aug. 8 and the ASEAN ministers will design the future course of the regional grouping, keeping in view the fast-changing global geopolitical situation and the power balance in Asia.

The second is signing or approval of a framework for a Code of Conduct (CoC) on the South China Sea (SCS) by ASEAN and Chinese foreign ministers during their Post-Ministerial Conference.

The dispute in the SCS threatens the unity and security of the 50-year-old ASEAN.

The SCS is an important waterway, the main source of transportation for one-third of global maritime trade or more than $5 trillion worth of goods a year. It is also rich in oil and gas and fishing resources

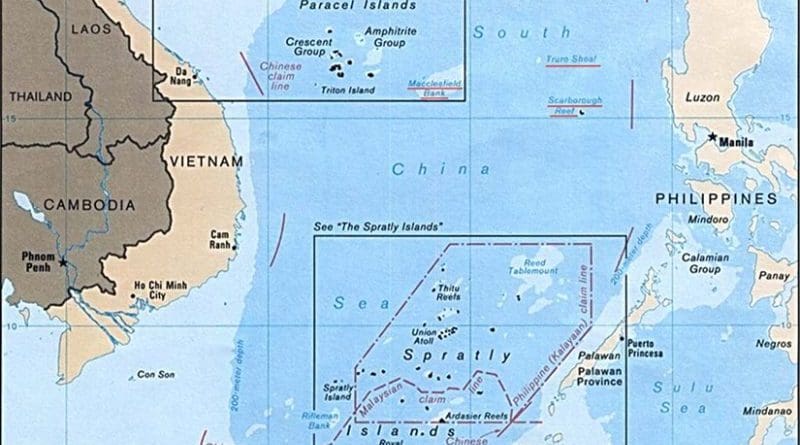

ASEAN member states like Vietnam, the Philippines, Malaysia and Brunei have overlapping claims with China and Taiwan to certain parts of the SCS, which has a maritime area of 3.5 million square kilometers.

But China claims more than 80 percent of the resource-rich SCS area, based on so-called “historical grounds” as well as a controversial “nine-dash” demarcation line. This line, the mother of all conflicts and controversies, also encroaches into a part of Indonesia’s Natuna maritime area, though the archipelagic state is not a claimant in the dispute.

Indonesia, the de facto leader of ASEAN, does not recognize China’s nine-dash claim in the SCS. Four ASEAN claimants, as well as the US, Japan, the European Union, India, Australia and many countries in the world also reject the claim, simply because China’s claim is not based on any international maritime law or convention.

Given the unequal balance between China and the ASEAN claimants in the SCS in terms of military strength and economic size, China has been pursuing its SCS maritime claims aggressively since 1970s when it used military force to take control of the Paracel Islands from Vietnam. Now its target is the Spratly Islands.

Using “coercive” methods, China has built numerous artificial islands through reclamation in recent years. Now it is turning them into military bases by building military facilities and deploying heavy weapons on those islands. Both claimant and non-claimant countries, including the US and Japan, believe that many of Beijing’s unilateral actions pose a serious threat to regional peace, security, freedom of navigation, overflight and legal fishing.

The Philippines took China to international arbitration in 2013 over the latter’s blockade of the Scarborough Shoal, which is located within the Philippines’ Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ).

In July last year, in a landmark decision, the Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA) in The Hague clearly ruled that China had no historic title over the waters of the SCS because China had signed the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) and ratified it. Under the UNCLOS, all coastal states are entitled to 12 nautical miles of territory from their coast, a continental shelf and a 200-nautical-mile EEZ.

A majority of countries have asked China to implement the PCA’s ruling as it is legally binding, but Beijing, which boycotted the court hearings, has rejected the ruling, which has been a major blow to Beijing’s international standing.

In an effort to improve its international image, China in May this year agreed to a framework agreement regarding a CoC on the SCS issue with ASEAN to reduce tensions and prevent conflicts in the contested waters. It took 15 years just to reach a framework agreement, not an actual CoC.

Of late, Chinese officials and media have been saying that by signing the framework agreement China is committed to maintaining peace and stability in the SCS and is ready to negotiate the CoC. With this CoC framework, which will be officially approved in Manila this week, China is projecting that the SCS problem is resolved. Is this so?

First things first, one should realize that there has been no change on the ground or in China’s SCS claims. The framework agreement is just a skeleton for the CoC. Nobody knows whether China will agree to a legally binding CoC. If it agrees, it will be a major breakthrough in the decades-old SCS conundrum.

But many scholars – both from China and outside China – are pessimistic because a legally binding CoC will not be in the interests of China. It will not be free to conduct the activities in which it is currently engaged in the Spratlys.

There will be two scenarios: The first one is that China may postpone or prolong the final CoC until all its objectives in the SCS are accomplished. Then it will sign it.

The second one is that it may dilute the contents of the final CoC so that there is no legally binding mechanism as such. For this China will continue use its present approach of wooing countries like the Philippines, Malaysia and Brunei through investment, trade and tourism.

Only Vietnam, the second-biggest claimant in the SCS after China, will remain a hard nut to crack for Beijing. Indonesia, which is a non-claimant country and has the biggest population and economy in Southeast Asia, will never comprise on its maritime rights in the SCS.

So the question is what ASEAN should do to secure a legally binding CoC that will be a comprehensive and effective in implementation. Because the CoC must contribute to ensuring peace, stability, security, safety and freedom of navigation and over-flight in the SCS and create a favorable environment to resolve any disputes by peaceful means and in accordance with international law, including the 1982 UNCLOS. Both China and all the ASEAN claimants, including Indonesia, have already signed the UNCLOS and ratified it a long time ago.

ASEAN ministers should not fall into China’s trap on the issue of the SCS and the CoC. China may inveigle them with economic incentives to comprise on the issue of the SCS. But ASEAN members must stick to their position of a strong and legally binding CoC that is based on the principles of international maritime law.

They must work hard in Manila to maintain consensus, solidarity and the central role of ASEAN in the SCS dispute and other regional and international affairs during their meetings.

ASEAN’s unity and centrality are the key to the grouping’s future.

“Unity and centrality must be nurtured,” Indonesian Foreign Minister Retno LP Marsudi said on July 19 at a one-day international conference on “Strengthening Cooperation and Inclusiveness” in Jakarta.

If this unity and centrality are not there, ASEAN will lose its relevance. That’s why ASEAN must demand with one voice that China should respect last year’s PCA ruling and work hard to conclude the CoC at an early date.

The CoC should not be diluted or delayed any further. After all, the CoC – which is not a solution to the dispute in the SCS — will be in everybody’s interest. Nobody wants war. We need a strong mechanism to prevent conflict and reduce tension. By signing a legally binding CoC, China will earn much needed international respect and prosper more from a peaceful environment in the SCS.