Syrian Statelets And Intelligence Games: Al-Sham’s New Mukhabarat – Analysis

By Carl Anthony Wege*

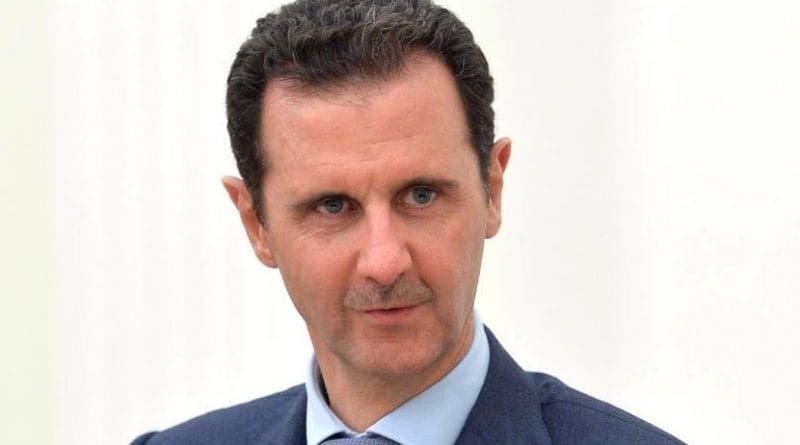

A novel Alawite-Shi’a security network may be developing in the Assad statelet now defining western Syria. It consists of an archipelago layered with remnants of the Bashar al-Assad-era intelligence organizations along with Iraqi Shi’a and other pro-Assad militias.

They are supported by Iran and Russia who separately struggle to integrate them all under the figurehead of Bashar Assad. This security infrastructure is emerging in the grey zone of conflict but is beginning to consolidate the many armed elements in western Syria opposed to Salafi Jihadism but having only cursory loyalty to Assad.

Bashar Assad’s pre-war regime in Syria was understood less by formal governmental institutions and more by a constellation of favored Alawite and Assad-affiliated families linked by marriage before the 2011 rebellion. The whole of Syria had been organized into a system where certain preferred families could enrich themselves with impunity irrespective of formal Syrian legal norms. The patronage networks created by Hafez and Bashar Assad during this era established a nominal Ba’athist secular modernity to overlay an Alawite dominated kleptocratic and Mukhābarāt state. Historically the intelligence services of Hafez Assad’s regime were built on four core agencies; the Idarat al-Amn al-Siyasi (Political Security Directorate) and Idarat al-Amn al-‘Amm (General Intelligence Directorate) that reported to the President through the Office of National Security of the Ba’ath Party. Additionally the Shu’bat al-Mukhābarāt al-‘Askariyya (General Military Intelligence) reported to the commander of land forces, and Idarat al-Mukhābarāt al-Jawiyya (Air Force Intelligence) reported to the head of the Air Force. These foundational intelligence agencies were ostensibly controlled by a National Security Council (or Bureau) and were supported by derivative agencies in a security network whose primary imperative was protection of the Assad (both Hafez and Bashar’s) dynasty.

These legacy intelligence services were largely unprepared when the winds of the Arab Spring blew into the souks and alleys of Damascus and Syria’s secondary cities. In those cities waited thousands and thousands of unemployed young men having migrated there to escape a devastating drought scorching the already economically marginal steppe lands (Badia) in eastern Syria. Now mobilized by aspirations for democracy and economic reform, the Syrian people began to rise as one. Assad sought to weather the reforming aspirations of his people that were unleashed by the Arab Spring, but as rhetoric turned to war Syria’s complex demography, long subsumed by the Ba’athist Mukhābarāt state, exploded in fratricide.

The Syrian rebellion became militarized by 2012 and the Sunni-dominated Syrian Arab Army (SAA) quickly disintegrated as long-buried sectarian divisions ignited an intercommunal firestorm beneath the political conflagration of Syria’s civil war. As the rebellion wore on Assad quickly lost control of events on the ground. Intervention by both Iran and Hezbollah proved inadequate to smother what by now was a legitimate revolution. Tehran, although willing to use whatever force necessary to preserve the Assad regime and its land bridge to Hezbollah, desired a light military footprint in Syria and resisted large scale deployments. Initially the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) and the Quds Lebanon Corps (then called Department 2000) was tasked by Tehran to restore what the Revolutionary Guard called alignment as the Syrian Rebellion escalated. While never reaching the levels later employed by Russia, Iran did deploy greater and greater numbers of specialized army units, Basiji and Saberin special operators, into the Syrian theater. Nonetheless by 2015 the Syrian Arab Army ceased to exist in any meaningful way, precipitating a grey zone conflict between army remnants, competing militias, and their various foreign sponsors. The eastern regions of Syria devolved into Salafi Jihadi badlands controlled by rival Salafi factions, many of whom were ultimately absorbed into the Islamic State (ISIS, ISIL, or Daesh) which itself is now fracturing under foreign military pressure. Only the massive Russian military incursion beginning in the fall of 2015 prevented the total collapse of what was by then a Russian allied pro-Iranian Statelet in western Syria. Supplementing direct troop deployments, Russian mercenaries fought for Assad directly along with hundreds of additional Russian fighters affiliating with various pro-Assad factions. Concurrently, the fratricide in western Syria became a more byzantine struggle between ethnic and religious groups complicated by massive internal population displacement. Western Syria’s Alawi population, however, remained geographically concentrated in the coastal Latakia Governorate abutting Jabal Nusayriyah. These Alawi generally aligned with the larger Syrian Shi’a and Ismaili communities and remained generally supportive of the regime even though the Latakian Governorate had to absorb thousands of refugees from other parts of the country.

Two loosely organized networks of armed groups were foundational in support for the regime in western Syria. The first and older of the two was the Shabiha, or Ghost Militia derived from the 1980s’ Latakia region mafia-style criminal gangs. The Latakian Shabiha criminal gangs were headed by Assad first cousins Fawaz Assad and Munzer Assad, providing unofficial support for the regime. They had been left to their own devices when the war broke out but were now adapting to the collapse of government authority and affiliating with apolitical gangs, local militias, and faux government entities to expand their presence in western Syria. More significant was the Jaysh al-Shab’bi (People’s Army), which emerged somewhat spontaneously from the Lijan al-Sha’bia (Popular Committees) of armed citizens originally intended for little more than defending local communities from outsiders. Assad later took advantage of these Committees and tried to combine them into the Quwat al-difa al-Watani (National Defense Forces or NDF), initially under the command of General Hawash Mohammed and sporadically affiliating with remnants of the SAA. However, by 2016 the NDF had disintegrated at the national level and their center of gravity in western Syria collapsed as most fighters shifted loyalty to local warlords capable of paying regular salaries.

By 2016 the Syrian civil war ground into a stalemate. Neither Russia nor Iran’s Revolutionary Guard operating through a façade Syrian sovereignty nor the eastern Syrian Salafi Jihadi factions had the strength to rule the whole of the country. Across this Hobbesian landscape, with hundreds of militias dividing, re-dividing, coalescing, and changing names, while controlling small and shifting parcels of territory, the only real focus was on local intelligence collection. Militia and other local actor notables cooperated to aggregate their knowledge of the local social hierarchy and kinship structures to develop intelligence that was essentially ad hoc but useful for local tactical purposes. However, over time, it may become possible for a faux Assad regime centered in the Latakia – Tartus rump statelet to begin to combine the intelligence generated by these local militias with an attendant infrastructure that can both consolidate power in the Alawite heartland and secure the fluid frontiers from Damascus to Aleppo. Consolidating local intelligence collection efforts into any embryonic security archipelago in the wider regions of western Syria presumes a nexus with the remnants of legacy Syrian governmental institutions, including Syrian Air Force Intelligence and the pre-civil war Military Intelligence Directorate along with fragments of the SAA and the NDF. Syrian Air Force Intelligence is the most significant legacy institution surviving into the current era having manifested the greatest organizational discipline. It is the most cohesive remnant of the regime intelligence agencies. Therefore, Air Force Intelligence will likely be the most significant legacy institution in any embryonic security archipelago.

To build a new Mukhābarāt state and such a security archipelago the regime must organize the numerous Shi’a affiliated militia fiefdoms and secular militias of different configurations dotting western Syria into a coherent security architecture stretching across the Damascus -Homs region and to the Lebanese frontier. In constructing such an architecture, a first objective for the Assad regime would be to get control of the streets in the towns and villages and to develop new informant systems on the ground to build a network that could exploit their collection activity. Over time, the regime will need to develop the necessary ability and authority to task such networks and logically aggregate information provided by such networks. Organizationally this must exploit residual NDF intelligence assets and interface with Hezbollah while successfully liaising with the Russian Sluzhba vneshney razvedki (SVR) and intelligence elements of the Revolutionary Guards Intelligence Directorate (Sazeman-e Ettelaat-e Sepah). Any new Mukhābarāt state will require the Assad regime to re-create national intelligence services. Russia may assist in this by resurrecting an analog of their 1970s KGB and GRU roles, but now training Syrian personnel in a wider spectrum of modern intelligence disciplines to include utilizing the strategic depth of virtual spaces for tradecraft models and information operations. Iran’s primary concerns in western Syria have a greater focus on maintaining a land bridge into Lebanon’s Shi’a territories. The role of Iranian intelligence organizations supporting a new Mukhābarāt state is likely a bit more limited. While a separate issue, Iranian and Russian political goals differ in Syria over the long haul and those differences may seed competition between them for influence in the Assad regime’s new security organizations. The challenge for the regime is to organize its intelligence infrastructure in a way that coherently encompasses the whole of the western Syrian space and provides a foundation for later expansion to incorporate the balance of territories defined by Syria’s pre-civil war borders.

Hezbollah’s relations with any post-war Assad regime’s new security organs consolidating along its frontiers would be a bit more complex. Hezbollah’s massive engagement in the Syrian war foreshadows a generation-long commitment between Hezbollah and any emergent Syrian Mukhābarāt. Anticipating such commitments, Hezbollah’s Intelligence Apparatus is now reproducing itself by seeding, with Iranian assistance, intelligence entities within the Iraqi Shi’a militias deployed across western Syria using the Hezbollah model. The geographic interface between the Hezbollah territories and the Assad regime is through the Lebanese ‘Shi’astan’ frontier on the eastern edges of the Anti-Lebanon (Al-Jabal Ash-Sharqī ) mountains running from Zebdani to the Hermel region in the northeast Bekka into the Qalamoun Mountains and Qusayr linking the Orontes River Basin with Damascus, Homs and Tartus in Syria’s Alawite regions. The Qalamoun was already a logistics reserve prior to the war housing Syrian SCUD and M600 Tishrin missiles as well as housing Syrian army ammunition storage areas. While no doubt cooperating with the Assad regime resources, what Hezbollah has committed in this region suggests it may pursue its own interests and take advantage of the chaotic circumstances to utilize part of the Qalamoun as a “new” Bekka for locating Hezbollah logistical assets while interfacing with the emergent Alawite-Shi’a intelligence organs.

Ted Robert Gurr modeled the pattern of ‘frustration-anger-aggression’ many decades ago in Why Men Rebel. Yet that anger and aggression came to naught as the democratic aspirations of the Arab Spring were found wanting in the face of Salafi Jihadism and the cold steel of Russian and Iranian geopolitical ambition. The Assad regime having lost half the country and teetered on the edge of extinction did not yield but now grows within it’s dead hulk a new Mukhābarāt to terrorize the remnants of a war-weary population.

About the author:

*Carl Anthony Wege in early 2017 became Emeritus Professor of Political Science at the College of Coastal Georgia, Brunswick, where he had taught since 1989. A graduate of Portland (Oregon) State University, with an M.S. from the University of Wyoming, Professor Wege has written extensively on Middle Eastern terrorism and related issues in a wide range of academic and professional journals.

Source:

This article was published by Modern Diplomacy