North Caucasus Islamist Insurgency And Security Of Sochi Winter Olympic Games – Analysis

By IPRIS

By Emil Souleimanov

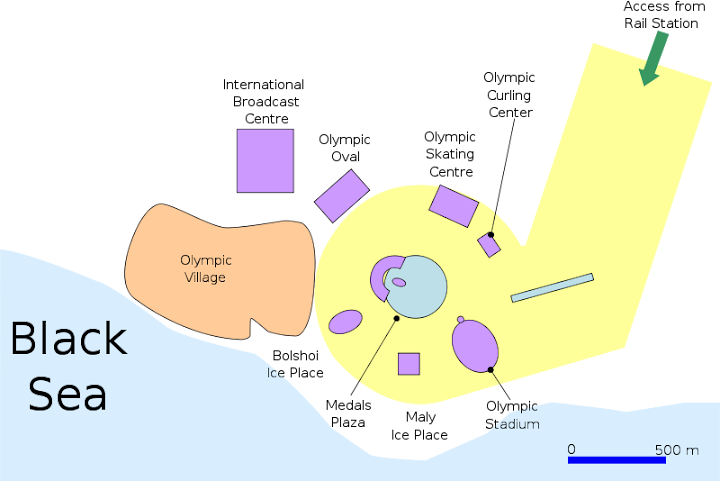

According to a recent announcement made by the Olympic Committee of the Russian Federation, around 70.000 workers of various professional backgrounds will provide their services for the upcoming Winter Olympic Games (WOG) of 2014 in Sochi, a Northwest Caucasian seaport city with a population of 350.000 people, situated in the Russia’s southernmost Krasnodar province. Within this number, an army of 25.000 volunteers, predominantly young men and women, recruited from across Russia will be established. This and some other factors, coupled with increased activities of the Western wing of the self-proclaimed Caucasus Emirate raise concerns about the ability of Russian authorities to provide security for a major international event of this scale and scope. This article is an attempt to explain the current security situation in and around the Sochi area with an emphasis on prospective terrorist-diversionary activities of the North Caucasus Islamist insurgents.

Background

It is obvious that Moscow considers a smooth realization of the WOG a major opportunity to improve the country’s image both at home and abroad, investing large sums of money into the organization of the Olympic infrastructure and its propagation worldwide. According to official estimates, the amount of direct state investment into the Olympics will make up as much as US$10 billion, with additional billions of dollars coming from the private sector. In the city of Sochi, a popular tourist destination, and its environments, as well as in the whole region of the West Caucasus, there are, however, some groups that are unhappy with the upcoming games.

Foremost among these groups are the North Caucasus Islamist insurgents. Having declared in the period of 2002-2004 a war of attrition against Russia, they have periodically carried out guerilla and terrorist attacks against both combatant and non-combatant targets, assassinating selected regime and pro-regime figures in the North Caucasus, a region largely claimed by them as part of an Islamic theocracy, which the insurgents had previously divided into separate territorial sectors. Moreover, they do not hesitate to assault indiscriminate targets in Russia proper, as well, causing high levels of civilian casualties. The lethality of their attacks in Russian cities has been on the rise recently as the insurgents seek to cause massive destruction of their adversary’s infrastructure and human resources. The most recent terrorist attacks, on the Moscow subway (March 2010) and Moscow’s Domodedovo airport (January 2011), testified to the insurgents’ ability to carry out full-scale operations even in a distant and unfavorable terrain, with the Kabarda-Balkaria-Karachay jamaat suddenly becoming one of the leaders of the North Caucasus insurgency.1

Second, there is the factor of Adyghe/Circassian nationalists2 who regard the Sochi area, especially the location called Krasnaya polyana, where the core of the Olympic infrastructure is to be built, as a mass grave containing bodies of thousands of indigenous Adyghes, mostly women and children, massacred during what they call the Circassian Genocide of the 19th century. This event marked the tragic culmination of a long period of warfare among the native populations of the Northwest Caucasus and the armies of the expanding Russian Empire. It is believed by some historians both within and outside the Adyghe community to have claimed lives of more than one million Circassians, with some Adyghe tribes fully exterminated, virtually all of them ethnically cleansed from the area and hundreds of thousands of survivors expelled from their historical homeland to the Ottoman Empire through the seaport of Sochi. Representatives of Adyghe nationalist organizations point to the fact that the WOG are to take place exactly on the 150th anniversary of the end of the Great Caucasian War in which Adyghe ethnicities, as noted above, took active part. Indeed, on May 24, 1864, symbolically again in Krasnaya polyana, the Tsarist army celebrated its final victory over the rebelling Adyghe tribes of what is now Krasnodar province. As of now, a big share of Adyghe organizations and the mainstream Adyghe public alike call for either a change of the location of the upcoming Olympics or an international boycott of it. According to some local sources, Adyghe nationalists were recently behind a bomb attack on a railway in the Sochi area as an act of discontent with the upcoming Olympics.3

Third, even though local inhabitants are generally eager to benefit financially from the wide range of opportunities that the upcoming Olympics will provide, some of them are deeply concerned with what they regard as a serious ecological catastrophe, as Olympic infrastructure is to be erected on the lands of the unique North Caucasus biospherical national reservation. Archeological sites dating back thousands of years are routinely being destroyed for the sake of building highways. It is not uncommon for Olympic infrastructure to be built with no or little respect to the private property rights of ordinary Sochians, whose houses and lands are taken away with inadequate compensation, the most notable case being the ongoing conflict between the inhabitants of the Sochi’s Imeretian valley and authorities.

Fourth, Georgian authorities have recently voiced protests against the upcoming Olympics pointing at what they claim to be the ongoing Russian occupation of the breakaway North Georgian provinces of South Ossetia and Abkhazia in the aftermath of the August 2008 war.4 It is also worth mentioning that Tbilisi has recently intensified its activism toward the North Caucasus autonomies in an attempt to push for its rather vaguely defined concept of the “United Caucasus” with Georgia in its core. Winning the hearts of the North Caucasians by providing them free entrance to Georgia and an opportunity to work and study without limitations is seen by Georgian strategists as a means to counterbalance Moscow’s interference in the internal affairs of this South Caucasus republic. However, it has already brought to bear significant criticism from both Russian authorities and among Georgian intellectuals who fear that this might serve as a basis for a further and potentially dangerous worsening of the country’s relationship with its neighbor to the north of the Greater Caucasus mountain range.5 Moreover, Georgian authorities have flirted with a possible recognition of the above-mentioned Adyghe Genocide, backing an international conference on this matter that took place in Tbilisi in March 2011, and proclaiming their prospective willingness to push for the genocide’s recognition on the international stage. This, again, resulted in Moscow’s protests, and, in a recent speech, the Russian president Dmitry Medvedev even pointed his finger at Georgia while talking about the Sochi Olympics’ security, without specifying his concern in detail.6 Being aware of its vulnerable standing vis-à-vis Russia and of the negative publicity of any potential destabilizing move on the international scene, Tbilisi will certainly make sure that no threat to the security of the Sochi Olympics is posed from Georgian soil.

It is also extremely unlikely that Georgian authorities truly reckon on the success of their effort to cancel the implementation of the Sochi Olympics, an effort that remains confined to the realm of verbal warfare. In fact, Tbilisi stands to gain the sympathies of the Adyghe communities both within and outside Russia, reducing the sense of Adyghe-Abkhaz solidarity.

Implications

It is obvious that Russian authorities are fully aware of the high level of terrorist threat during the upcoming WOG in Sochi and will do their best to reduce to a minimum any risk of attacks. Both Vladimir Putin, the country’s Prime Minister, and Medvedev, along with other high-ranking state officials, have repeatedly expressed that priority is being placed on the Olympics’ security. Already now, with the launch of construction work, Russian security forces carry out strict control of people, transport and goods at Olympic sites using updated technologies. It is believed that around US$2 billion will be invested in the Olympics’ security which is a record amount so far.7 Intriguingly, as Islam Tekushev points out, an unofficial ban has recently been put on the participation of North Caucasian companies in public tenders for construction work in the Sochi area. Moreover, the labor force of the North Caucasus ethnic autonomies is not being hired for construction of Olympic projects, which has already stirred up inter-ethnic tensions in the region.8 Precise requirements for selecting volunteers are not yet known, as the official recruitment process is scheduled to start in the early months of 2012, but it is very likely that similarly discriminative criteria will be applied to make sure that potentially unreliable natives of North Caucasus autonomies are kept away from the WOG infrastructure. It is likely that a special regime will be introduced during the WOG in the whole of the Krasnodar province that will be upheld by members of federal security forces transferred specifically for this purpose from Russia proper to minimize the risk of insurgents’ and their sympathizers’ infiltration into the WOG infrastructure. As of yet it is believed that around 50.000 officers of the Ministry of Interior will be serving in the area during the Olympic Games, with the members of Sochi police providing an additional 3.000 officers for security. A significant contribution of Ministry of Defense troops, as well as the Black Sea navy and special antiterrorist regiments will be deployed in the Sochi area during the course of the Olympic Games.9 According to local sources, no security forces from the North Caucasus autonomies will be placed in the area either before or during the Games.10 Interestingly, the current trend of Russian secret services, conscious of the general unreliability of local security forces in their hinterland, is to act on their own, avoiding even informing the locals of the forthcoming major anti-terrorist raids, as was the case in a massive anti-terrorist assault in the mountains of Ingushetia in March 2011.11 The optimal outcome for the Russian security forces would logically be to put an end to the Caucasus Emirate before the actual start of WOG at all, but given Russia’s generally ineffective methods and the very diffuse organization of the Islamist insurgency in the North Caucasus this task seems unachievable.

The question of whether or not North Caucasus insurgents will be considering terrorist attacks on the WOG infrastructure, further alienating international community, will depend mainly on their actual agenda and technical capabilities as of 2014. As of yet, the insurgents have refrained from making any formal statements. With regard to the internal radicalization of the insurgency movement in recent years, however, and with little sympathy from the outside world to the North Caucasus insurgency, attacks can be expected to be rather high-scale and indiscriminate should they occur. After all, realization of an event of this range and scope in the vicinity of insurgent centers is unique, as it provides the Islamists a welcome opportunity to let the entire world know about themselves and their political aspirations, moreover on soil they claim as their own. As the Islamists have proven their ability to use human bombs during their terrorist attacks, it remains highly debatable whether the authorities will be in a position to routinely control hundreds of thousands of locals and international guests on a relatively large territory making sure no single terrorist attack is carried out in crowded areas during the Olympics. Indeed, as Islamists generally use suicide bombers while carrying out large- scale attacks in an adversary’s terrain, they do not have to care about exit routes of the attacker, which increases the destructive force of their assaults, further providing the advantage of surprise and complicating anti-terrorist measures.

Seen from the Russian perspective, the 2014 Olympic Games will test the contested ability of federal security forces to effectively coordinate the work of tens of thousands of people grouped in a wide range of agencies. This ability has traditionally been their weakest side, a fact frequently proved during massive anti-terrorist raids. Widespread corruption, especially in the ranks of police forces, remains a major problem and it is very unlikely that it will disappear overnight in Russia’s probably most corrupt region. As Sergey Markedonov points out in this regard, “as long as the major goal of our [Russian] police is wearing down ordinary people and secret forces deal with mythical ‘Orange revolutions’ and foreign NGOs, we will be having an extremely vulnerable security of Olympic facilities, etc.”12

The authorities’ desire to reduce the risk of terrorist attacks by preventing native populations of the North Caucasus from taking part in the construction of WOG infrastructure is also questionable as in the Krasnodar province in general, and Sochi area in particular, they are rather strong demographically. After all, the Krasnodar province contains Adyghean autonomous republic within its administrative borders and locals cannot be simply isolated from the area for the duration of Olympic Games. Besides, carrying out overtly discriminate measures against them is likely to stir up already significant inter-ethnic tension between the groups of North Caucasian natives and the Russians, forging a sense of internal solidarity among North Caucasians, boosting their anti-Russian sentiment, and strengthening their support for Islamist insurgents in a way that might be effectively used by the latter. In turn, resentment toward (North) Caucasian natives will be increased among local Russians, strengthening administrative discrimination toward the North Caucasians and stepping up further militarization of the Cossack units that have traditionally been seen as a counterbalance to the increasing socio-economic and political influence of the North Caucasians due to their demographic growth in the area. Relevantly, xenophobia has been on the rise in Russia with anti- Caucasian sentiments prevailing in this particular part of the country.13 Furthermore, it is unclear as yet how the authorities will be treating children from ethnically mixed, i.e. Slavo-Caucasian, families or the natives of the South Caucasus.

Finally, disaffection with the upcoming Olympics is the strongest among the Adygheans who consider themselves natives to the area, yet are still discriminated against by the Russian majority. General disaffection of the local inhabitants with what they consider the unfair activities of the authorities related to the construction of Olympic facilities further deteriorates the conflict potential of the Sochi area. The Georgia factor, however, is most likely to remain irrelevant as far as the security of the upcoming Olympics is concerned.

Conclusion

The upcoming WOG in Sochi raises a number of significant security concerns. If not the Caucasus Emirate in its entirety, then at least particular segments of the North Caucasus Islamist insurgency are very likely to view the 2014 Olympics as a historically unique opportunity to gain global publicity. In order to carry out a successful attack in heavily enemy-controlled terrain, indiscriminate suicidal bombing is most likely to be used, for that tactic would provide for high lethality in the targeted population. In light of serious internal problems and the overall environment, the ability of Russian authorities to ensure security of the WOG is highly questionable.

Since the Western wing of the insurgent Kabarda-Balkaria-Karachay jamaat group consists of members of Adyghe ethnicities and has been increasingly active in the overall insurgent movement, nationalist motives might also play a role in rallying militant Islamists and Adyghe nationalists together; Adyghe insurgents could seek to portray the implementation of the WOG in the Sochi area as a lack of respect to their massacred and ethnically cleansed forebears, and as a sheer sign of humiliation by some others. One should not entirely rule out that certain segments of Adyghe nationalists might temporarily join the Islamist insurgency, or establish their own ranks to carry out retaliatory attacks in the Sochi area either before or during the the Olympic Games. Finally, by concentrating heavily on security in the Sochi area, the Russian authorities risk revealing their flank and providing the insurgents easier opportunities to assault Moscow, Saint Petersburg, or other cities in the North Caucasus or Russia proper. As the whole of the world will be watching the WOG, any major attack on Russian soil will bring about negative global media attention for the Russian government, positive propaganda for insurgents, and a further setback in Russia’s efforts to control its hinterland.

This article was supported by the Research Intent of the Faculty of Social Sciences of Charles University in Prague MSM0021620841.

Author:

Emil Souleimanov

Assistant Professor at the Department of Russian and East European Studies, Charles University, Prague, Czech Republic

Source:

This article was published by IPRS under the original title of “The North Caucasus Islamist insurgency and the (in)security of the Winter Olympic Games in Sochi (2014)” and may be accessed here (PDF), and appeared in PORTUGUESE JOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS | NUMBER 5 | SPRING/SUMMER 2011, pages 66-71.

Endnotes:

1 See, for instance, Emil Souleimanov, “Kabardino-Balkaria Risks Becoming New Insurgency Hotspot” (The Central Asia and the Caucasus Analyst, 2 March 2011).

2 Both terms, Adyghe and Circassian or Cherkes, are used interchangeably to describe a group of peoples inhabiting the Northwest Caucasus (Adygheans, Cherkes, Kabardey, Abazas) that speak a mutually intelligible language. Members of this language group use the term Adyghe to refer to themselves; this term is used throughout this study, as well. The Abkhaz people are also linguistically related to the Adyghe ethnicities forming the Adyghe- Abkhaz language family. Interestingly, strong ties of ethnic solidarity exist among the members of Adyghe and Abkhaz peoples and during the Abkhazia war of 1992-1993, numerous Adyghe volunteers participated on the side of the Abkhaz against Georgian troops. However, the Abkhaz do not use the term Adyghe as an auto-ethnonym.

3 Alina Lobzina, “Terrorist attack on Sochi railway” (The Moscow News, 22 November 2010). 4 “Georgia starts battle against Olympics in Sochi” (RT, 22 November 2010).

5 See a summarizing analysis by Giorgi Kvelashvili, “Will Georgia Recognize the Circassian Genocide?” (Jamestown Foundation Blog, 22 March 2010).

6 Dmitry Medvedev specifically said: “You all understand that there are also certain problems connected to our neighbor, Georgia”. See Amie Ferris-Rotman, “Russian leader warns of threats to Sochi Olympics” (Reuters, 18 February 2011).

7 “Sochi-2014. Safe and unproblematic?” (Russia-IC, 25 February 2011).

8 Author’s personal interview with Islam Tekushev, an expert on the Northwest Caucasus (5 April 2011).

9 “Black Sea Fleet to secure Winter Olympics in Sochi” (Vesti.RU, 22 March 2011).

10 Author’s personal interview with Islam Tekushev (5 April 2011).

11 Author’s personal interview with an officer in the Ministry of Interior of Ingushetia, (30 March 2011).

12 Author’s personal interview with Sergey Markedonov, an expert on the Caucasus (6 April 2011).

13 For a detailed overview of the problem, see, for instance, Tatiana Lokshina, “Nationalism, Xenophobia and Intolerance in Contemporary Russia” (Moscow: Moscow Helsinki Fund, 2002). See also Aldiyar Autalipov, “Russia: Xenophobia on the rise” (ISN Security Watch, 22 January 2009).