TPP Countries Near Agreement Without US Participation – Analysis

By CRS

By Ian F. Fergusson and Brock R. Williams*

On November 11, 2017, the 11 remaining signatories of the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) agreement, excluding the United States, announced the outlines of the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), with a final deal reportedly possible in 2018. The CPTPP would be a vehicle to enact much of the TPP, signed by these countries and the United States in February 2016.

TPP has been stalled since President Trump withdrew from the pact in January 2017. The withdrawal was the first action under the President’s new trade policy approach, which includes a stated preference for bilateral free trade agreement (FTA) negotiations over multiparty agreements like TPP, a critical view of many existing U.S. FTAs, and a prominent focus on bilateral U.S. trade deficits as an indicator of the health of trade relationships.

The Trump Administration is now also engaged in a renegotiation of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) with Canada and Mexico, two TPP signatories and CPTPP participants; it is also seeking potential amendments to the U.S.-South Korea FTA (KORUS).

While the United States is not involved in CPTPP, the agreement has the potential to affect the economic well-being of certain U.S. stakeholders, as well as U.S. leadership on international trade issues and long-standing U.S. promotion of an open, rules-based trading system. It also may strengthen perceptions of U.S. disengagement in Asia, which many analysts say could impact the U.S. ability to pursue other goals in the region.

Congress, which oversees and sets objectives for the Administration in trade negotiations and passes legislation to implement U.S. FTAs, could play an important role in U.S. trade policy responses to the CPTPP. The United States has existing FTAs with six of the CPTPP members with many provisions similar to those in the new agreement, including near complete tariff elimination. This suggests the most significant economic effects for the United States may relate to the CPTPP members without a U.S. FTA, notably Japan, Malaysia, and Vietnam. The new CPTPP would enter into force 60 days following the ratification of the agreement by 6 of its members.

Suspension of TPP Provisions

In order to preserve U.S. interest in the TPP, Japan, which is now leading the CPTPP negotiating process, has pushed for the CPTPP to suspend TPP provisions where consensus could not be reached, rather than amend them. The parties agreed to suspend 20 provisions, which primarily were sought by the United States and agreed to by other countries in return for access to U.S. markets. This was especially true in the area of intellectual property rights (IPR) where the CPTPP suspended provisions on

- patentability for inventions derived from plants;

- patents for new uses, processes, or methods of existing products (so-called evergreening);

- patent term adjustment for marketing and patent approval delays; protection of undisclosed test data for chemical and biological drugs;

- the author/creator life +70 year copyright term;

- legal liability and safe harbor provisions for internet service providers; circumvention and digital rights management;

- protections of encryption and satellite program and cable signals.

In the investment chapter, investor-state-dispute-settlement (ISDS) is suspended with respect to investment screening (e.g., the criteria by which a party approves an investment), and also with respect to investment agreements between a host state government and an investor. These changes potentially could lead to a requirement to use domestic courts and apply domestic laws to resolve some investment disputes, counter to longstanding U.S. objectives in bilateral investment treaties and FTAs.

In e-commerce, the parties suspended the obligation to review de minimis tariff levels on express shipments. The parties also removed a provision to “promote compliance” with local labor laws in the procurement of goods or services, and one section of a provision related to the prohibition against illegal trade in wildlife. In the event of the return of the United States to the agreement, reinstatement of the suspended provisions would require consensus among the existing parties. The parties still must resolve four specific issues, which include Canada’s desire for a blanket cultural exclusion (rather than the narrower chapter-by-chapter exclusions in the TPP) and Malaysia’s exceptions to state-owned enterprise (SOE) commitments.

Concerns over Effects on U.S. Export Competitiveness

U.S. stakeholders in export-oriented industries have raised concerns that an enacted CPTPP could disadvantage U.S. firms and workers in CPTPP markets. Tariff schedules are expected to remain consistent with the original TPP agreement, which would eventually result in the elimination of duties on more than 99% of tariff lines in each CPTPP country (95% for Japan), and a greater number of tariff reductions.

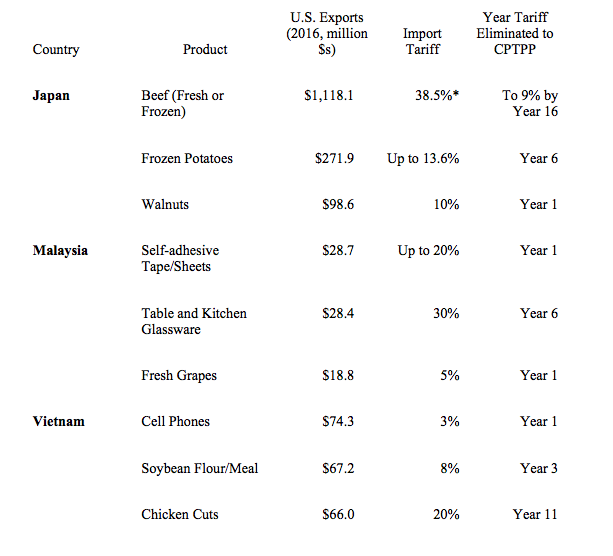

For generally high-tariff products such as agricultural goods, this tariff differential on U.S. versus CPTPP country exports could be a significant factor in market competitiveness. For example, U.S. beef exports to Japan, which totaled more than $1 billion in 2016 face a 38.5% tariff in the Japanese market which eventually would be reduced for CPTPP country exporters to 9%. Table 1 provides examples of high value U.S. exports to the largest three CPTPP markets without an existing U.S. FTA, and the associated tariffs that would be eliminated for CPTPP countries. CPTPP also addresses nontariff barriers and establishes trade rules, but these commitments are typically applied in a nondiscriminatory manner and hence could still benefit U.S. trade even without U.S. participation.

Table 1. Selected U.S. Exports to CPTPP Countries without U.S. FTA

Notes: Based on original TPP tariff schedules, which may not necessarily reflect final CPTPP tariff elimination.

(*) U.S. beef exports to Japan currently face a 50% tariff due to a temporary safeguard measure. Japan’s existing FTA partners, such as Australia, are exempt from the safeguard.

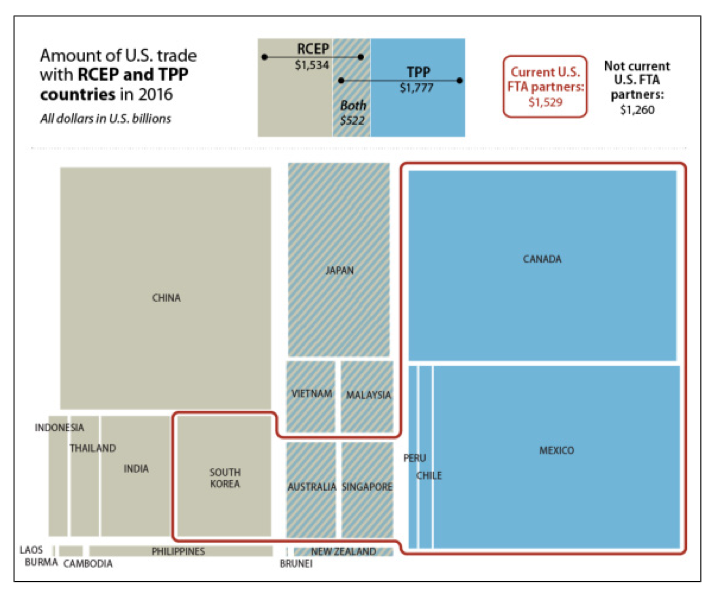

In addition to the CPTPP, several TPP countries are also participating in the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) (see members in Figure 1). While RCEP negotiations are less comprehensive than the CPTPP, if it were to move forward, RCEP could also potentially disadvantage U.S. exporters as tariffs are reduced among the members, which include all major U.S. trading partners in the region.

Outlook and Implications

The CPTPP enters the trade landscape at a time of uncertainty in the global trading system. Much of this uncertainty, felt particularly in Asia, reflects ambiguity in the direction of current and future U.S. trade policy goals and U.S. leadership in establishing international trade rules and institutions.

Related to this is an ongoing contentious domestic debate over the costs and benefits of international trade and trade agreements. CPTPP has significant policy implications for the United States and Congress. The agreement includes longstanding objectives of U.S. FTAs such as broad tariff elimination and a “negative list” (more liberal) approach to services trade liberalization, as well as newer, largely U.S.-crafted commitments on digital trade and SOEs. The agreement, however, could also make significant changes to the original TPP on issues like IPR and investment that were U.S. priorities. Moving forward, the agreement may raise questions for U.S. policymakers, such as

- Were the United States to seek entry to the CPTPP, how difficult would it be to reestablish the suspended provisions?

- Will other countries seek to join the CPTPP? If so, how will this affect U.S. trade patterns with those countries?; and

- How will U.S. absence from two major potential regional trade initiatives affect broader U.S. influence in the Asia-Pacific region?

*About the authors:

Ian F. Fergusson, Specialist in International Trade and Finance

Brock R. Williams, Analyst in International Trade and Finance

Source:

This article was published by CRS as CRS Insight IN10822 (PDF)