Temperatures In South China Sea Continue To Rise – Analysis

Chinese military drills in South China Sea, as ASEAN convenes on code of conduct, send unsettling message.

By Gregory Poling*

Chinese forces recently held a series of military exercises in the South China Sea that spotlighted once again its neighbors’ concerns about Beijing’s bullying. The People’s Liberation Army Navy on July 20 declared a large section of water south and east of Hainan off-limits to foreign ships from July 22 to 30 due to the exercises. It’s not unusual for naval forces to conduct exercises in the South China Sea – indeed, the United States does so with regularity – but the scale, location and exclusionary zone were unusual, turning this series of exercises into a microcosm of China’s alarming behavior in disputed waters. The exercises sent a message that does not bode well for the region’s stability.

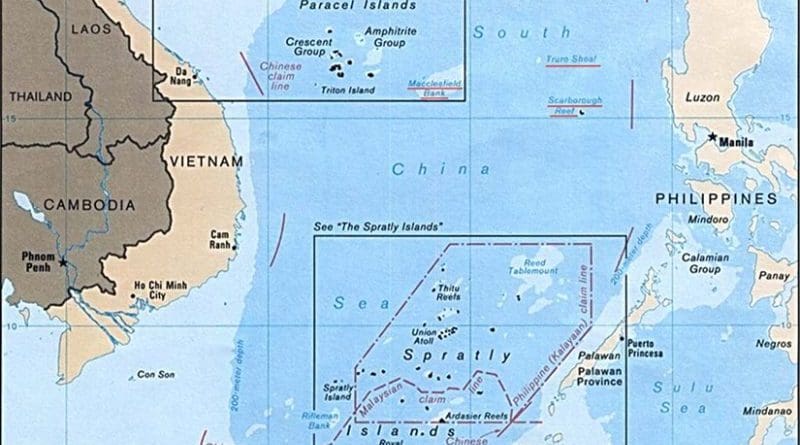

Vietnam quickly denounced them because the area declared off-limits included waters around the Paracel Islands, a matter of dispute between Beijing and Hanoi. By declaring a large swath of water, most beyond China’s territorial waters, off-limits to vessels, Chinese authorities went beyond the bounds of international law and normal state practice. The declaration also underscored China’s increasingly dismissive attitude, suggesting its neighbors’ claims are not only incorrect, they are irrelevant.

According to Chinese state media, more than 100 ships, some nuclear-armed, and dozens of aircraft fired hundreds of missiles and other ammunition in a show of force. Chinese forces also practiced information warfare, electronic countermeasures and amphibious landing drills. China’s neighbors would be forgiven for assuming that such unilateral, large-scale display was meant to send a message. As Australian National University’s Rory Medcalf suggested to the Financial Times, the exercises seem to be “a needlessly excessive show of force.”

Chinese state television cautioned that the exercises were in the works for more than a year and not meant to intimidate. Such reassurances fall on deaf ears in the region after 18 months of breakneck island building by China over other claimants’ objections, six years of escalating tensions in the South China Sea and serious provocations like the 2012 seizure of Scarborough Shoal from the Philippines and the 2014 deployment of an oil drilling platform in disputed waters.

The timing sends an unsettling message to regional states regarding China’s willingness to negotiate a peaceful settlement. The exercises overlapped with a high-level gathering of senior officials from China and the 10 members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, ASEAN, in Tianjin for their ninth meeting on the implementation of the Declaration on the Conduct of Parties in the South China Sea. That 2002 agreement is non-binding, failing to prevent the escalating tensions, and was supposed to be an interim step on the path to a legally-binding code of conduct. Beijing has continuously blocked serious progress toward a binding agreement, and despite official pronouncements of “friendly and candid” discussions, there is no indication that the ninth meeting moved the parties any closer to a code of conduct than did the last eight.

China’s exercises wrapped up just ahead of the August 4 ASEAN Foreign Ministers’ Meeting and the August 6 ASEAN Regional Forum, which includes 26 Asia-Pacific countries plus the European Union. The South China Sea disputes have featured prominently in both annual meetings in recent years. In 2012 disagreement between the host Cambodia, which relies heavily on China for economic and diplomatic support, and the other ASEAN states over whether to mention the South China Sea in the foreign ministers’ joint statement led to the organization’s first failure to issue a statement.

Chinese Vice Foreign Minister Liu Zhenmin on August 3 insisted that this year’s meetings should not include discussion of the South China Sea, though Reuters reported that same day that a draft of the foreign ministers’ statement already included concern about recent developments “which have the potential to undermine peace, security and stability in the South China Sea.” Liu’s statement was emblematic of China’s regular opposition to discussion of the disputes in multilateral forums, especially with the United States present – and, delivered just after 10 days of large-scale war games in disputed waters, probably ensured the atmosphere would not be conducive to productive discussions.

Provocations like the military exercises prompt neighboring states to seek closer relations with one another and with the United States to balance against what’s perceived as a potentially aggressive rising power in the region. Fellow South China Sea claimants, particularly the Philippines and Vietnam, are more strenuously contesting Chinese claims – most visibly via Manila’s ongoing arbitration case in The Hague. Chinese bullying undermines Beijing’s narrative that a rising China will be a responsible player on the regional and global stages.

One of the most visible results of China’s activities in the South China Sea is that regional states have welcomed the US security presence in Asia with an eagerness not shown in decades. The United States and the Philippines in early 2014 signed an Enhanced Defense Cooperation Agreement to allow greater numbers of US troops, ships and planes to deploy to the Philippines on a rotational basis. It would also allow the US military to pre-position equipment in the Philippines to better respond to emergencies and upgrade military infrastructure at Philippine bases for use by both militaries. That agreement is held up in the Philippine Supreme Court, but if implemented could prove a game changer for the Philippines’ external defense, marking a new era in the bilateral alliance.

Perhaps even more impressively, the United States and Vietnam have moved with incredible speed to strengthen their relationship and put the ghosts of their past behind them. In 2012 then-Secretary of Defense Leon Panetta made a landmark visit to Cam Ranh Bay in 2012. The next year President Truong Tan Sang visited Washington, and the two countries signed a comprehensive partnership. In late 2014, the White House relaxed the longstanding ban on US exports of weapons to Vietnam to allow maritime security-related arms transfers, and then in early July 2015, Communist Party of Vietnam General Secretary Nguyen Phu Trong met with President Barack Obama in the White House – a scene that even the most optimistic watchers of the relationship would not have predicted a few years ago.

Southeast Asian states are pulling closer together. For instance, the Philippines and Vietnam signed their own strategic partnership. Low-level multilateral exercises are held under the ASEAN umbrella or led by regional states like Indonesia. China’s fellow claimants are also strengthening their security relationships with other outside countries, particularly Japan, which is in the middle of a historic redefinition of its defense guidelines. For example, the Philippines is receiving 10 coast guard patrol vessels from Japan, and during a recent trip to Tokyo, President Benigno Aquino III signed an agreement on defense industry cooperation and began discussions of a visiting forces agreement for Japanese troops in the Philippines.

Such developments are not in China’s long-term interests. While the United States is benefitting from a renaissance of goodwill in Southeast Asia and a nascent web of security relationships develop among Asian states, China’s stumbles should not be seen as victories for the United States or any other country. Extralegal claims and rising tensions in the South China Sea threaten the global maritime commons and stability in the Asia Pacific, interests for both China and the United States. The challenge is convincing Beijing that it has a greater stake in preserving those interests than in securing uncontested control over the South China Sea.