Currency-Printing: South Asia-South Korea’s Trustworthy Relations In 1980s – Analysis

By Institute of South Asian Studies

South Korea’s currency-printing technology was well-received in many Asian countries in the 1980s when they encountered currency shortage crisis and outsourced currency printing. In South Asia in particular, India, Bangladesh, Bhutan, and Pakistan were the countries where ‘made-in-Korea’ banknotes and coins were circulated. Further, South Korea’s currency- printing technology was transferred to some countries like Bhutan for it to produce its currency notes indigenously. Such export of currency notes whose printing was outsourced to South Korea and the country’s technology transfer to South Asian state-customers is significant, in the sense that (1) possessing its own and producing the unique national currencies of other countries enhance South Korea’s state legitimacy and power, and (2) South Korea-South Asia relations have been built based on such mutual trust and confidence.

By Sojin Shin1

Possession of a unique national currency within the geographical extent of territory is considered as an indispensable component of sovereignty because currency strength is closely linked to state legitimacy and power. Such national monetary strength will be constrained if the multiple currencies of a certain country including coins and banknotes are not sufficiently circulating in the national territory.

The shortage of currency production is one of the occasions. The failure of managing money supply will also affect the macroeconomic management like inflation control. Many of Asian countries in the 1980s had the lack of currencies for some reasons. In most of the cases, the shortage stemmed from the lack of technology to establish their own mints and the lack of capacity to produce the high quality and enough quantity of currencies.

In the currency shortage crisis, South Korea was the lead of exporting banknotes and coins to many countries in Asia. In South Asia in particular, India, Bangladesh, Bhutan, and Pakistan were the countries where ‘made-in-Korea’ currencies were circulated. The South Asian countries made their money supplier to test both technology and security standards. At that time, South Korea’s currency-printing technology was advanced enough to compete with other Western countries that exported banknotes and coins to many countries in Asia.

Considering outsourcing currencies can easily involve with financial security setbacks, South Asian countries must have built trust and confidence toward South Korea. It meant that the South Asian countries considered South Korea as a trustable partner that they can bear sovereignty and security problems. For South Korea, production of currencies for South Asian countries meant more than business for such reasons.

India’s Coin Shortage Crisis in the Mid-1980s

There was a period of domestic currency shortage in the 1980s in India when the Government of India needed to import coins to cater to the demand of the people. Three mints—Hyderabad, Bombay, and Calcutta—were producing coins at that time, but their production capacity did not meet the request. They produced 525 million pieces of coins in 1981-82, 650 million pieces in 1982-83, and 1 billion pieces in 1983-84. The Government of India targeted to provide 2 billion pieces of coins for the year 1985. However, the capacity of the three mints was up to around 1.3 billion pieces.

Their lack of production capacity to mint coins became the trigger for the Coinage Bill Amendment in 1985. Vishwanath Pratap Singh who served as the Minister of Finance and Commerce proposed the Coinage Bill Amendment in the meeting of Parliament to import coins from foreign countries. 2 Many of the Members of Parliament (MPs) criticized the Government’s dysfunction over the issue. They pointed out that the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) did not adequately function to lift coins from the mints. The shortage of coins meant that the weaker section of citizens using them more often encountered difficulties. It made some of the MPs more upset over the agenda. In addition, the MPs were worried about the financial security as minting of coins in other countries may occur the currency smuggling issue.

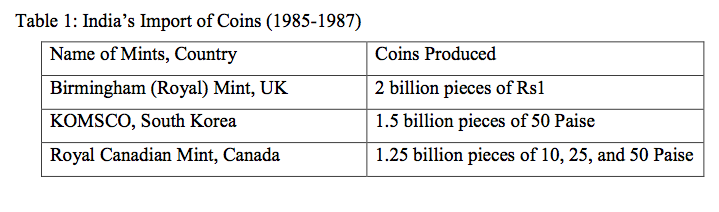

Despite the concerns, the Government of India decided to import coins from other nations to meet the target of securing 2 billion pieces of coins in 1985-86. Three foreign mints were asked to produce coins for India—Birmingham Mint in the UK, KOMSCO in South Korea, and Royal Canadian Mint in Canada. Table 1 presents the number of coins imported from the three foreign countries to India during the period 1985-1987.3 The total cost for the imported coins was around 300 crore rupees at that time.

Korean Mint’s Outstanding Performance in Currency-Printing for South Asia

According to the Korea Minting Security Printing & ID Card Operating Corporation (KOMSCO), KOMSCO participated into the bid for the contract of producing 50 paise coins and succeeded. Shinjo Kang, who served as the CEO of KOMSCO from 1985 to 1989, told that he could not remember how the bid went yet reminded of the export of coins to India as a significant experience to expand KOMSCO’s business to other countries in South Asia.4

KOMSCO wrote that workers in the Korean mint work in three eight-hour shifts without having any holidays to meet the export demand from India.5

KOMSCO could increase the additional 25% of coin production in 1986 for export to India thanks to the workers’ efforts.6 In 1986, KOMSCO won the two times of contract for exporting 750 million pieces of 50 paise coins and supplied the coins without any setback. At that point, an official visited KOMSCO from India for a preliminary inspection. He was unable to distinguish disqualified coins from qualified coins that KOMSCO selected. KOMSCO wrote that the inspector realized that the preliminary inspection process was not necessary for such elaborate workmanship and went back to India before the schedule.

In fact, Bangladesh was the first country in South Asia to which KOMSCO exported currencies. KOMSCO was successful in the bid for the contract of producing 100 million of 20 taka banknotes in 1977.7 KOMSCO noted that there were only around 20 countries in the world having the capacity of producing their currencies with advanced technology at that time. For getting the bid for Bangladesh, KOMSCO had to compete with other European mints including the UK’s Thomas De La Rue company. KOMSCO seemed to lose its cooperative relations with Thomas De La Rue after succeeding at the export contract with Bangladesh in 1977 as Thomas De La Rue also aimed at the bid. Despite the severe competition with other European mints, KOMSCO could manage to bid for the contracts of producing differing types of banknotes such as 5, 20, and 50 taka bills for Bangladesh until 1989 (see Picture 1-A). Bangladesh established a mint by then, yet its technology was not reaching to produce high- denomination notes. The total export of taka banknotes from South Korea to Bangladesh during 1977-1989 was around US$9.4 million.8 Further, KOMSCO also provided prize bond, a kind of certificate of deposit, which needed a higher quality than banknotes for the prevention of forgery for Bangladesh during the same period.

After making and exporting banknotes and coins to Bangladesh and India successfully, KOMSCO began to negotiate with the Bhutanese government to win a bid for another contract in 1987. KOMSCO finally obtained the order and provided 13.5 million pieces of four types of banknotes—10, 20, 50, and 100 ngultrum—for the Bhutanese government in 1989 (see Picture 1-B).9 The total export of ngultrum banknotes from South Korea to Bhutan in 1989 was about US$315 thousand.

Further, KOMSCO provided US$71 thousand worth of banknote paper for one rupee notes for Pakistan in 1987.10 The Pakistani government requested more banknote paper from South Korea in 1989. However, KOMSCO could not make a contract with Pakistan due to its limited supply. KOMSCO’s production capacity already reached the peak by then due to increased export.

Technology Transfer to Royal Monetary Authority in Bhutan

Bhutan had imported all types of banknotes and coins from Europe before KOMSCO supplied the four types of banknotes in 1989. After that, the Bhutanese government was content with the quality of made-in-Korea notes and requested South Korea to assist in establishing a mint that could produce its domestic currencies.11 In fact, South Korea initially planned to provide a fund for Bhutan to support the mint-building project. However, Bhutan decided to use the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP)’s aid for the project. In April 1990, South Korea and Bhutan signed a contract for the project to build the Royal Monetary Authority (RMA). The contract stipulated that South Korea would provide necessary machines to produce and examine currencies, technology transfer to workers from Bhutan, and assistance for the coinage reform.

As part of the coinage reform, the Bhutanese government also asked South Korea to design the both sides of six differing types of coins—5, 10, 25, 50 chetrum, 1 and 5 ngultrum. By then, the design was not consistent among the same denominated coins because the coins were imported from various countries from Europe. The inconsistent design of coins made not only foreigners but also local citizens confuse with their coins. KOMSCO provided a new set of design for the six types of coins in August 1990: the design included previous monarchs, Buddhist symbols like fish and lotus flowers. It also offered technology transfer for the workers visited South Korea from Bhutan and necessary assistance to operate RMA in 1991. KOMSCO sent five workers from South Korea to Bhutan to support technology service in the RMA for 14 months when RMA was established in 1991.

South Korea’s Currency-Printing for Other Asian Countries

South Korea’s currency-printing technology was well-known not only in South Asia but also to other Asian countries such as China, Philippines, Thailand, Indonesia, and Singapore. KOMSCO exported US$72 thousand worth of 1 and 5 yuan coins to China from 1973 to 1982. For the Philippines, it supplied seven types of government stamps from 1972 to 1980. KOMSCO made a contract with the Thai government in 1985 to provide US$720 thousand worth of banknote paper for 50 baht bills. It continued to export the banknote paper for 50 baht and 500 baht bills to Thailand until the early 1990s. In 1986, KOMSCO shipped 116 million pieces of three differing types of coins—10, 20, and 50 cent—to Singapore.

Conclusion

South Korea’s currency-printing technology was well-received in many Asian countries in the 1980s when they encountered currency shortage crisis. South Korea’s exporting currencies to those countries at that time meant something beyond its success of business, because importing domestic currencies from foreign countries can easily involve with financial security setbacks. It meant that not only South Korea’s currency-printing technology was a world-class level but also South Korea’s bilateral relations with the countries were firmly based on trust and confidence. India, Bangladesh, Bhutan, and Pakistan were the countries in South Asia where ‘made-in-Korea’ banknotes and coins were circulated. Furthermore, South Korea’s currency- printing technology transfer to Bhutan was significant in a sense that possessing and producing unique national currencies closely links to national monetary strength.

Source:

This article was published by ISAS as ISAS Insights No. 357 (PDF)

Notes:

1 Dr Sojin Shin is Visiting Research Fellow at the Institute of South Asian Studies (ISAS), an autonomous research institute at the National University of Singapore. She can be contacted at [email protected]. The author, not ISAS, is liable for the facts cited and opinions expressed in this paper. The author would like to thank KOMSCO’s Overseas Strategy & Business Team and Hoasun Shin for providing KOMSCO’s data.

2 See the Government of India, “The Coinage (Amendment) Bill, 1985,” Rajya Sabha Debate, 17 May 1985 (Accessed on 14 September 2016).

3 See the Government of India, “Import of Coins,” Rajya Sabha Debate, 2 August 1988 (Accessed on 14 September 2016).

4 Author’s phone interview on 13 July 2014.

5 KOMSCO (1986), The 35 Years of History in KOMSCO [Hangukjopyegongsa 35nyeonsa], Daejeon: KOMSCO. P .239.

6 Ibid., p.240.

7 Ibid., p.237.

8 KOMSCO (1991), The 40 Years of History in KOMSCO [Hangukjopyegongsa 40nyeonsa], Daejeon: KOMSCO. P .277.

9 Ibid., p.278.

10 Ibid., p.286.

11 Ibid. pp.281-82.