The Indian Elections And The Rural Sector – Analysis

By Institute of South Asian Studies

The increasing visibility of farmer distress towards the end of 2018 and the results from the recent state elections reveal the significance of the farmer vote. Looking at both the farmer protests and the caste protests, in relation to Prime Minister Modi’s promises, reveal the causes behind the recent farmer protests. A growing attempt to win over the farmers is predicted in the run up to the 2019 general election.

By Diego Maiorano and Vani Swarupa Murali *

India’s prolonged and deepening agricultural crisis will have a significant impact on the forthcoming national elections, which will be held in the spring of 2019. India has been affected by a long-lasting agricultural crisis, stemming from long-term problems and some new issues that have surfaced under the government of Prime Minister Narendra Modi. In 2018 alone, there have been at least 15 large-scale farmers’ protests, which are becoming “the new normal”.1

Two-thirds of India’s population live in rural areas, of which a large part is employed in the agricultural sector.2 In terms of workforce, 33 per cent of the Indian population is employed in services, 24 per cent in industry and the largest chunk, 43 per cent, in agriculture.3

That such a vast proportion of the population is employed in agriculture makes the rural world particularly important in electoral terms.

In fact, 342 out of 543 seats are rural and “unlike in the US, where poorer households turn out to vote less than wealthier urban citizens, it’s the less advantaged rural India that decides elections.”4

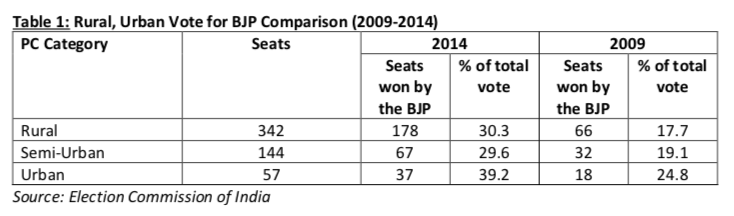

The BJP’s win in 2014 was largely credited to the party’s ability to expand its traditional, mainly urban, vote base and to win over a high number of rural seats from the INC.5 As the table below shows, the BJP won 112 more rural seats during the 2014 elections, as compared to 2009, securing 178 rural seats and 37 urban seats.6

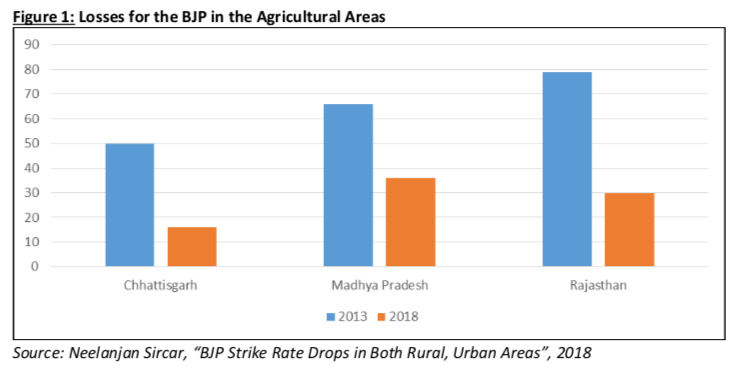

The BJP’s recent loss in three state elections with a high proportion of rural voters, Chhattisgarh, Rajasthan and Madhya Pradesh, signalled that the farmers’ unrest can have dramatic electoral consequences for the ruling party.7

Figure 1 shows the seat share won by the BJP in agricultural areas during the recent state elections.8 The BJP’s tally dropped significantly in all three states. Significantly, the BJP’s seat share dropped the most in areas with a high proportion of farmers.9

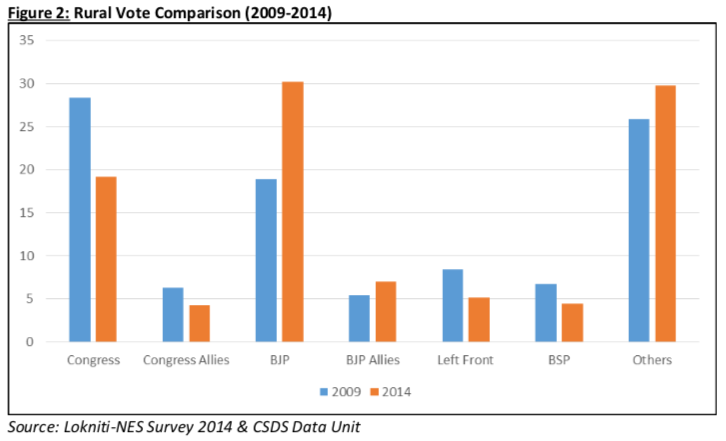

Figure 2 shows the percentage of rural vote clustered by the party during the 2009 and the 2014 national elections.10 Historically, rural voters have voted for the Congress or other regional parties, while the BJP’s vote base lay amongst the richer, better educated, upper caste groups.11 At the 2014 elections, however, the BJP was able to draw support from a much broader section of the electorate, cutting across caste and class.12 As can be seen from the graph, the dip in the Congress’ rural vote share translated into a rise in the BJP’s rural vote share. Whether the BJP will be able to keep its rural base intact will be a major determinant of the 2019 Indian elections.

Causes of Farmer Distress

Agrarian distress is not new. Long-term factors include lack or inefficient state support; limited access to institutional credit and high levels of indebtedness; high input costs and declining landholding size; shift to cash crops without adequate support systems in place; vulnerability to volatile international commodity prices and low (and declining) public investments in the agricultural sector.13

Farmers have also become increasingly disgruntled with their situation due to reoccurring cycles of – large investments on inputs (fertilisers, seeds, pesticides, etc.) [often through rapacious moneylenders), crop failure (increasingly due to climate change], inability to pay back the loans and thus, an inability to meet daily domestic needs. Public investments, which, have been declining in the last two decades, aggravated the farmers’ vulnerability.14

Adding onto these existing long-term factors, recent triggers have caused a surge in the number of agrarian protests since Modi became Prime Minister in 2014. First, the Minimum Support Prices – the prices at which the Food Corporation of India purchases food from farmers – have been stagnating for three years, although they have been recently increased. Second, the price of certain inputs have dented farmers’ (already very low) profit margins. During Modi’s term, the cost of fuel, fertilisers and pesticides increased by 26, 15, and 30 per cent respectively.15 Third, price crashes of several crops have further deteriorated farmers’ incomes. Fourth, the demonetisation of 86 per cent of the country’s currency implemented in November 2016 led to a severe shortage of cash – on which the rural economy largely relies – which impacted farmers’ ability to obtain credit, purchase inputs and sell their produce.16 These factors deepened the farmers’ distress dramatically and resulted in numerous farmers protests, including in the national capital. Compounding on this, many agrarian families whose daughters and sons are now educated and seeking employment opportunities in cities are unable to find them in a context of almost jobless growth.17 This not only frustrates educated youth with a rural background, but also causes a shortage of labour and impacts workers’ productivity, as those working in the fields are becoming older and older.

Modi’s Promises

A key electoral promise of Narendra Modi in 2014 was to double farmers’ income by 2022, through higher public investments in agriculture-related infrastructures and other forms of support.18 The plan to double farmer’s income by 2022 has been implemented through various schemes such as the issuance of soil health cards, the launch of an online platform called e-NAM to find out the right prices for crops in the market without middlemen, crop insurance schemes and irrigation programmes.

However, the success of these schemes have been limited19 and did not offset income shocks such as demonetisation. For instance, an assessment of e-NAM revealed that only a small number of transactions were conducted and farmers did not benefit much from wider price awareness or reduced commissions.20 Likewise, the crop insurance scheme had limited effectiveness as many of the state governments did not include cultivation costs into the insurance’s coverage21 and private insurers have little incentives to pay farmers their due.22 Some state governments also did not pay out the premiums by the due date, leaving farmers’ claims without reimbursement.23

That the government has been particularly effective at tackling farmers’ distress is evident from the unusually high number of farmers’ protests that occurred during Modi’s term. These assumed two main forms.

First, in a number of states, agricultural castes – such as the Jats in Haryana, the Marathas in Maharashtra and the Patels in Gujarat – mounted agitations asking for reservations in educational institutions and government jobs. These protests have also occurred with the Gujjars in Rajasthan and the Kapus in Andhra Pradesh.24 These caste groups have traditionally been dominant in their states – which make them electorally crucial – mainly because of their large populations and the large proportion of land owned by the community. 25 A section of these communities used their economic and political dominance to expand their reach to other sectors of the economy.26 However, a sizable part of the community have been hardly hit by the decades-long agricultural crisis and failed to find decent jobs in the urban sector, given the difficulty of the Indian economy to generate enough jobs. This sparked off protests and demands for reservations, which are however difficult to accommodate, given that current reservations already cover the maximum amount of posts that can be legally reserved.

The second type of farmers’ protests concerned more directly agriculture. Farmers’ organisations have been asking higher procurement prices, loan waivers, and lower input prices. This type of demands is easier for the government to meet. In fact, news report suggest that the government might be announcing soon a package of support for farmers, just ahead of the 2019 elections.27

Conclusion

The impact of farmer distress on elections was made clear during the 2017 Gujarat election, when the BJP could hold its citadel only because of the votes of the urban voters – which, unlike in most other Indian states, are a majority. Most rural seats went to the Congress party. Despite the BJP retaining a majority in Gujarat, the Congress was successful in winning a large number of rural seats in areas, particularly were at the centre of the Patel caste protests.28 They nearly doubled their number of seats from 15 in 2012 to 28 in 2017, out of the 48 seats available.29 On the contrary, the BJP won 30 seats in 2012 but only 19 in 2017.30 This shows the extent to which the farmer vote could influence election results.

The CSDS-Lokniti Mood of the Nation Survey 2018 reported that dissatisfaction with the Modi administration was highest amongst the farmers. The BJP has thus commenced various mechanisms to retain its electorate, including a mass-contact campaign by BJP legislators.31 More concrete forms of support are likely to be announced in the next few months. This would be on top of several state- level initiatives. The governments of Assam, Maharashtra, Punjab and Karnataka have all approved farm loan waivers in the past few years. After being elected in Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh and

Chhattisgarh, the INC waived farm loans within two days32 and has promised to take similar measures if elected in states like Haryana that go to polls in 2019.

As the race to the general elections in 2019 picks up, we can expect both parties to step up their attempts to win over the farmers. The 2017 election and the 2018 assembly elections have proven the significance of the farmer vote. While it is notoriously difficult to predict the result of Indian elections, what we can be sure of is that the farmers’ distress will play a significant role in determining the results.

*About the authors: Dr Diego Maiorano is a Visiting Research Fellow at the Institute of South Asian Studies (ISAS), an autonomous research institute at the National University of Singapore (NUS). He can be contacted at [email protected]. Ms Vani Swarupa Murali is a Research Analyst at ISAS. She can be contacted at [email protected]. The authors bear full responsibility for the facts cited and opinions expressed in this paper.

Source: This article was published by ISAS (PDF)

Notes:

- Arun, Srinivas, “Why Farmer Protests May Be the New Normal”, livemint, (19 July 2018) https://www.livemint.com/Politics/cjW8GmkZpCq8TzSpeDky0H/Why-farmer-protests-may-be-the-new- normal.html. Accessed on 3 November 2018.

- Data taken from the World Databank at: databank.worldbank.org/.

- Ibid.

- Alyssa, Ayres, Our Time Has Come, (New York, N.Y, Oxford University Press, 2018).

- Jason, Burke, “Indian Election 2014: Your Interactive Guide to the World’s Biggest Vote”, (The Guardian, 2014) https://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/apr/07/-sp-indian-election-2014-interactive-guide- narendra-modi-rahul-gandhi. (Accessed on 24 December 2018)

- Data taken from the Election Commission of India at: eci.gov.in.

- Diego, Maiorano & Archana, Atmakuri, “Elections in the Hindi belt – Why the BJP should be worried”, (ISAS Briefs, 631, 2018); Ronojoy, Sen, “Assembly Poll Result Boosts Congress and Stings BJP” (ISAS Insights, (528), 2018)

- Neelanjan, Sircar, “BJP Strike Rate Drops in Both Rural, Urban Areas”, (New Delhi, Hindustan Times, 12 December 2018) https://www.hindustantimes.com/chattisgarh-elections/bjp-strike-rate-drops-in-both- rural-urban-areas/story-4nxyl3Y22knj4b8Z0HzEbK.html. Accessed on 16 December 2018

- Ibid

- Data from Lokniti-NES Survey 2014 and CSDS Data Unit.

- Sanjay, Kumar & Pranav, Gupta, “Why the BJP Needs to Reach out to Rural Voters”, (Livemint, 30 January 2018) https://www.livemint.com/Politics/IK0WIwd9K1CS9kPDVNwRcK/Why-the-BJP-needs-to-reach-out- to-rural-voters.html. Accessed on 3 November 2018

- Eswaran, Sridharan, “Class Voting in the 2014 Lok Sabha Elections – The Growing Size and Importance of the Middle Classes”, (Economic & Political Weekly, 49(39), 27 September 2014) https://www.epw.in/journal/2014/39/national-election-study-2014-special-issues/class-voting-2014-lok- sabha-elections. Accessed on 10 December 2018

- Priscilla, Jebaraj, “Why are Farmers all over India on the Streets?”, (The Hindu, 8 December 2018) https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/why-are-farmers-all-over-india-on-the- streets/article25698970.ece. Accessed on 10 December 2018; K.C. Suri, “Political Economy of Agrarian Distress”, (Economic & Political Weekly, 41(16), 22 April 2006) https://www.epw.in/journal/2006/16/special-articles/political-economy-agrarian-distress.html. Accessed on 12 December 2018

- Himanshu, “Rural Push in Budget 2016-17”, (Economic & Political Weekly, 51(16), 16 April 2016) https://www.epw.in/journal/2016/16/budget-2016–17/rural-push-budget-2016-17.html. Accessed on 10 December 2018

- Priscilla, Jebaraj, op. cit.

- Neelanjan, Sircar, “BJP Strike Rate Drops in Both Rural, Urban Areas”, (New Delhi, Hindustan Times, 12 December 2018) https://www.hindustantimes.com/chattisgarh-elections/bjp-strike-rate-drops-in-both- rural-urban-areas/story-4nxyl3Y22knj4b8Z0HzEbK.html. Accessed on 16 December 2018.

- Santosh, Mehrotra; Ankita, Gandhi; Partha, Saha; Bimal Kishore, Sahoo, “Turnaround in India’s Employment Story”, (Economic & Political Weekly, 48(35), 31 August 2013) https://www.epw.in/journal/ 2013/35/special-articles/turnaround-indias-employment-story.html. Accessed on 25 November 2018.

- Priscilla, Jebaraj, op. cit.

- S. Narayan, Farm Distress in India – Causes and Possible Remedies, ISAS Insight No. 530, 20 December 2018.

- Ashok, Gulati & Siraj, Hussain, “Three years of Narendra Modi government: In Agriculture, the policy mix is right but implementation poor”, (Financial Express, 2017).

- Ibid.

- S Narayan, Farm Distress in India – Causes and Possible Remedies, ISAS Insight No. 530, 20 December 2018.

- Ashok, Gulati & Siraj, Hussain, “Three years of Narendra Modi government: In Agriculture, the policy mix is right but implementation poor”, (Financial Express, 24 April 2017). https://www.financialexpress.com/opinion/three-years-of-narendra-modi-government-in-agriculture-the- policy-mix-is-right-but-implementation-poor/639360/. Accessed on 10 December 2018.

- Christophe, Jaffrelot, “Why Jats want a Quota”, (The Indian Express, 23 February 2016) https://indianexpress.com/article/opinion/columns/jats-reservation-stir-obc-quota-rohtak-haryana- protests/. Accessed on 16 December 2018.

- Mridul, Kumar, “Reservations for Marathas in Maharashtra”, (Economic & Political Weekly, 44(14), 4 April 2009) https://www.epw.in/journal/2009/14/commentary/reservations-marathas-maharashtra.html. Accessed on 10 December 2018.

- Diego, Maiorano, “Caste protests in Delhi spring from deep economic distress”, The Conversation, 25 February 2016.

- “Farmers package in the works: Income support scheme and interest-free loans”, Indian Express, 15 January 2019.

- Ronojoy, Sen, “Elections In Gujarat: A Close Win for the Bharatiya Janata Party”, (ISAS Brief 534, 2017).

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Vikas, Pathak, “BJP Leaders to Tour U.P. Villages Before Lok Sabha Poll” (New Delhi, The Hindu, 23 October 2018) https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/other-states/bjp-leaders-to-tour-up-villages-before-lok- sabha-poll/article25302841.ece. Accessed on 25 November 2018.