What China Stands To Gain If Assad Falls – Analysis

By Daniel Wagner and INEGMA

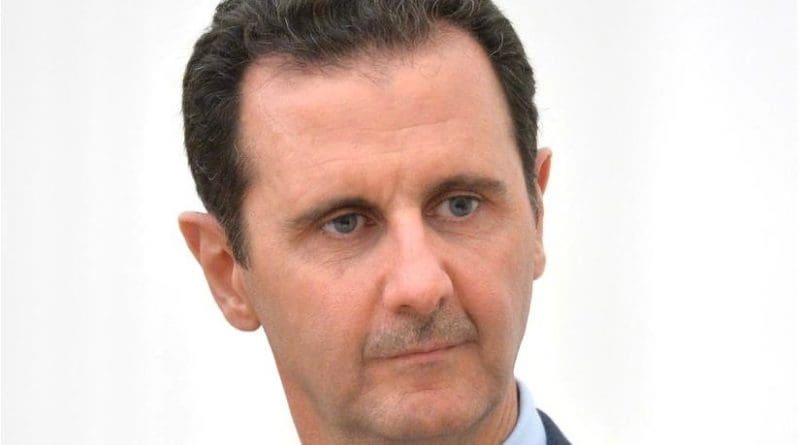

President Assad’s inevitable fall from power, presumed to be later this year, will be important for many reasons – among them, a possible shift in the geo-strategic balance of the Middle East and how today’s ‘great powers’ wield their batons and attempt to manipulate the marionettes on the ground. China, Russia and the U.S. have been engaging in a not so delicate diplomatic dance, as each positions itself to impact the eventual outcome of the Syrian drama. To date, China and Russia have had the most impact by exercising their UN Security Council veto, preventing the U.S. and West from doing something similar in Syria to what NATO did in Libya last year.

Russia has much to lose in Assad’s potential downfall, given its 40+ year history as a client state, its military assets in Syria, and Syria’s current role as a battleground for future political influence in the region. While Russia’s issues are more related to regional history, its military support of Mr. Assad, and its own military presence in the country, China’s issues are more ideological. China and Syria have had diplomatic relations since 1956 and have developed a common understanding of what is in each other’s best political interests. For example, China supports Syria’s political position on the Golan Heights, and Syria supports China’s view vis-à-vis Taiwan, Tibet and Xinjiang province.

Moreover, China sees Syria as a testing ground for how political change unfolds in the Middle East in the future. Having abstained from UN Security Council Resolution 1973, which paved the way for NATO intervention in Libya, China was not in the end rewarded for doing so. In stepping aside at the UN, China in essence negated its own long-held position against interference in another country’s affairs, for which the Chinese government was criticized at home for acceding to western demands and compromising its own principles. Meanwhile, its failure to provide overt support to the NATO military campaign left China open to criticism in Libya for not supporting the democratic movement there. So the Chinese government was harshly criticized for not blocking UNSCR 1973.

In Syria, China does not intend to make the same mistake twice. It views such interventionism as tangentially linked to the possibility of western interference in China’s own proxy states, or indeed in China itself. The question of supremacy in global political affairs looms large, and China ultimately sees Syria as a firewall – if the West prevails in Syria, China may find it more difficult to influence the course of events in other countries of geostrategic significance going forward.

China has in essence adopted a combination of ‘wait and see’, and ‘have its cake and eat it too’ by embracing a two-pronged strategy. On one hand, China has bought Mr. Assad some much needed time to determine if his regime may in the end prevail, while not ruling out possible future support for anti-Assad forces. At the same time, China has ramped up its own diplomatic efforts, having dispatched delegations throughout the region to act as an honest independent broker. Doing so has demonstrated a degree of sophistication not previously seen in conflict-torn regions. China must believe it needn’t play the game the way the west wants to play it, while preserving its own future options.

China has relatively little to lose economically, no matter how the Syrian drama plays out. Bilateral economic relations between China and Syria are not significant, with a little more than $2 billion in two-way trade between the two countries, almost entirely composed of Chinese exports to Syria, according to the IMF. But China sees Syria as an important trading hub, and part of its historical Silk Road, which it would like to preserve if possible.

More important to the Chinese are the long-term implications of political change in Syria. Whether the west likes it or not, China is a player of growing importance in the Middle East. Given the animosity toward the U.S. that has developed in the region since the onset of the Arab Awakening, China must figure it can benefit by maintaining a low profile while remaining engaged in the process in less conventional ways.

Whoever prevails in Syria is likely to want to have China on its side, so China’s go slowly, remain engaged in the background, and be prepared to support whoever comes out on top approach will undoubtedly yield benefits in due course. If Mr. Assad prevails, China can say it never stopped supporting him. If anti-Assad forces prevail, China can say it neither supported nor opposed Mr. Assad – keeping its options open in a fluid and unpredictable situation.

Whether anti-Assad forces would perceive this as genuine and whole-hearted is not really the important point. What is important is that China can extend a hand of friendship to whoever prevails and have a better chance of securing a meaningful long-term relationship, than if it had been less nimble and open minded. Neither Russia, Turkey, nor the US can say that. As such, China may end up beating the great powers at their own game in Syria.

For the greater Middle East, this has broad implications. China is unlikely to adopt a different approach to political change in the region if its approach in Syria works well. One could envision a similar approach working in any number of GCC countries, should the need arise. Given China’s growing economic and political importance, few countries in the region will want to have China as an enemy. Rather, they are likely to embrace a China that is seen as pragmatic, open minded, and supportive.

Daniel Wagner is CEO of Country Risk Solutions, a cross-border risk consulting firm based in Connecticut (USA), and author of the new book Managing Country Risk (www.managingcountryrisk.com). He can be followed on Twitter at: http://twitter.com/countryriskmgmt.