After The Showdown In Libya’s Oil Crescent – Analysis

A renewed struggle this summer over Libya’s main oil export zone cut sales in half, squeezing hard currency supplies amid outcry about mismanagement of hydrocarbon revenues. To build trust, Libyan and international actors should review public spending and move toward unifying divided financial institutions.

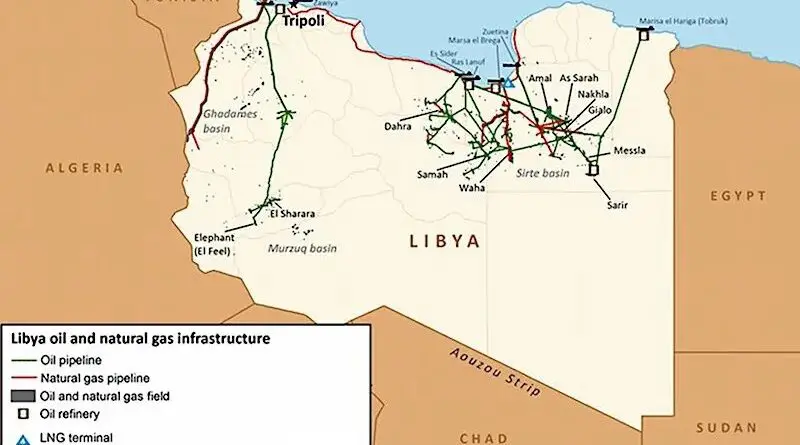

Fighting in June in Libya’s “oil crescent”, a coastal area home to most of its oil export terminals, led to a brief military takeover of oil installations and, subsequently, an attempt to deepen the institutional schism between the internationally recognised government in Tripoli and its eastern rival.

These scuffles halved Libya’s oil exports, causing a dramatic drop in hard currency revenues and a shock to an economy heavily dependent on imports of consumer goods and already on the verge of col-lapse. A crisis was averted when the eastern government reversed course, but underlying grievances remain unresolved.

The first step forward is an international review of the two rival Central Banks’ operations, which should lead to the banks’ reunification. Other steps include greater UN engagement with the east and addressing the question of securing petroleum facilities in future negotiations on the restructuring of the security sector.

The nearly month-long standoff over crude oil export terminals in eastern Libya is over. But another could soon emerge if the underlying causes of the conflict are not addressed. On 11 July, the Libyan National Army (LNA), the force that controls the east, announced that it would resume collaboration with the National Oil Corporation (NOC) based in the western city of Tripoli, reducing the risk of deepening the country’s institutional divides and worsening its already profound economic crisis. But Libyan and international stakeholders must capitalise on the LNA’s decision by easing competition for control over the country’s resources and financial institutions and tensions over the mismanagement of public funds. Otherwise, popular grievances will persist and renewed armed confrontation is possible.

The oil terminals crisis unfolded in three stages. It started on 14 June with an offensive led by Ibrahim Jedran, a former Petroleum Facilities Guard commander, in the so-called “oil crescent”, an eastern coastal area from which more than half of Libya’s crude oil is exported. Jedran’s attempt to seize control was short-lived: the Libyan National Army recaptured the oil crescent within a week.

In late June, the struggle evolved into a larger feud over control of oil and gas revenues. The LNA’s commander, Field Marshal Khalifa Haftar, announced that he would no longer allow the Tripoli-based NOC to manage oil sales from eastern terminals, putting in charge a previously inactive Benghazi-based NOC established when state institutions split in 2014. International condemnation was swift, as the eastern NOC has no legal authority according to UN Security Council resolutions. The result was an immediate shutdown of oil sales from eastern Libya: there were no buyers for oil sold by an illegal entity. The country’s exports fell by 50 per cent, further starving the economy of hard currency.

Haftar reversed course on 11 July, under intense international pressure and encouraged by several gestures by Tripoli. Most important was the request made by the head of the Presidency Council of the internationally recognised Government of National Accord, Faiez Serraj, to the UN Security Council to establish an international committee to oversee an independent review of the disbursement of funds by Libya’s Central Bank. Haftar has also demanded such a review. He and his supporters also see opportunities to push for a new “unity” government and to reopen the question of who should run the country’s economic and financial institutions.

Neither a unity government nor new leadership at economic and financial institutions will be easy to achieve, given deep institutional divides, accumulated mistrust since 2014 and, most important, conflicting interests among Libyan actors jostling for positions in a new set-up. International stakeholders’ strict adherence to the Libyan Political Agreement, the UN-approved governing framework in place since December 2015, will also limit efforts in this direction.

For this reason, the parties should not miss the opportunity provided by Serraj’s call on the UN to review the Central Bank’s disbursements. It is an essential first confidence-building step that could pave the way for unifying the country’s divided institutions. The two sides have yet to agree on whether the review should include a financial audit, who should carry it out or with what precise objective. The UN Support Mission to Libya (UNSMIL) could help them define the terms. Ideally, the review would be carried out by an international auditing firm with the support of UNSMIL, the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund.

The aim should be to produce a transparent overview of the Central Bank’s financial transactions since 2014 as a basis for the government’s monetary and fiscal policies rather than investigating alleged corruption or dictating who should be in charge of the institution. Such a review would be insufficient to resolve the economic crisis, root out endemic corruption or prevent a military escalation. But it would send a strong signal that stakeholders are serious about bridging the country’s divides, reunifying the Central Bank and stabilising the country.

To reach these goals, UNSMIL will need to increase its footprint in eastern Libya and act as a bridge between the Tripoli-based institutions and their rivals in the east, which will have to be engaged to end the institutional divides. Additionally, it should help Libyan authorities flesh out a new consensual strategy on the composition and chain of command of forces deployed to secure hydrocarbon facilities to prevent competing claims of legitimacy from becoming a new trigger for war.

The events in the oil crescent should remind everyone that Libya’s conflict has economic as well as political and military dimensions. Any strategy aimed at stabilising the country must address all three components in an integrated manner. Policymakers – including the UN, relevant member states and Libyan authorities – recognise the conflict’s many layers. Yet, over the years, they have continued to prioritise the crisis’s political dimension and offered mainly political solutions – most recently, elections – to unite the country. Without more progress to heal the rifts in the country’s economic and financial institutions, military and political divides are likely to become further entrenched, rendering the prospect of a political settlement all the more remote.

Full report may be read here

Excellent report and analysis as it does reflect the reality in Libya.Now after 7 years of getting ride of Gadhafi`s regime the UN must put more pressure and enforce the law to show all the current factions in Libya that Patience is running out.Rallying the People and encouraging them to demonstrate Peacefully in the streets can be very effective method to bring a change and force all current Meletias and those who are holding political and military positions to the change of the current stat of the country.