From Aid To Inclusion: A Better Way To Help Syrian Refugees In Turkey, Lebanon, And Jordan – Analysis

By ECFR

By Kelly Petillo*

Introduction

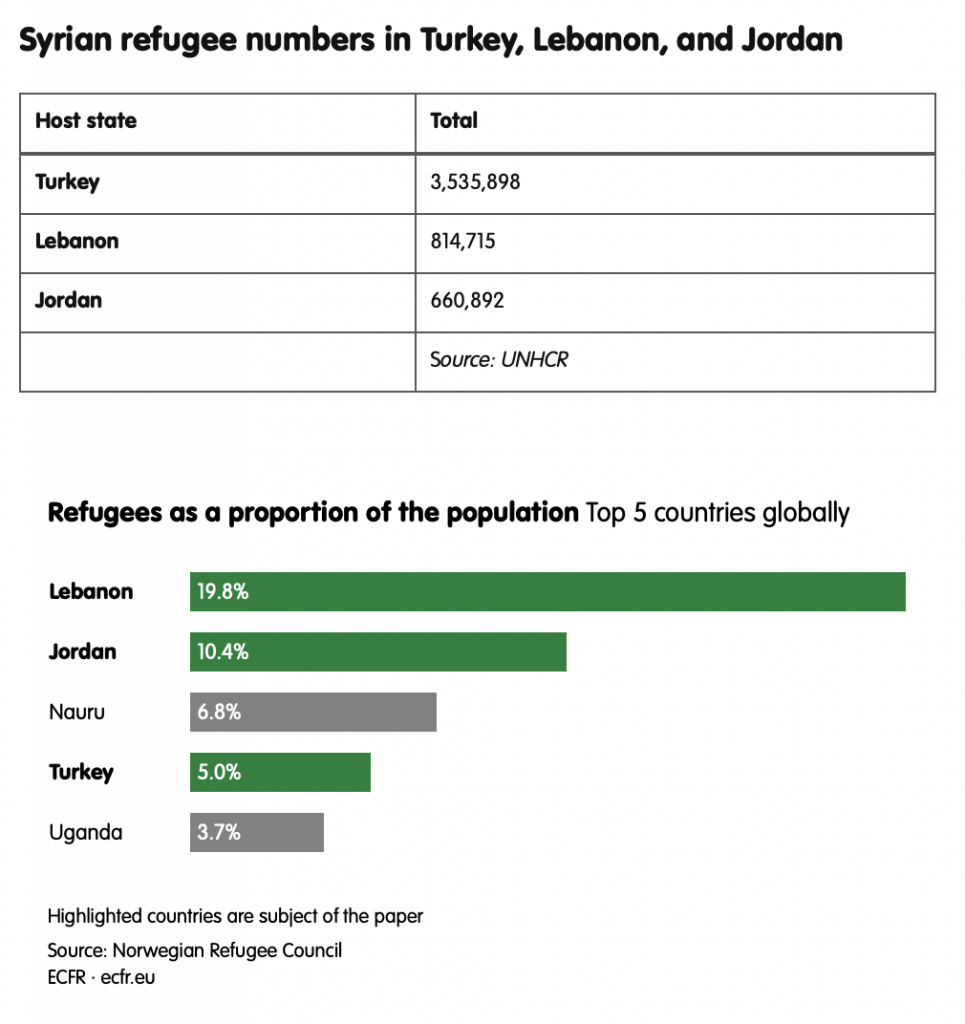

Nearly 12 years since Syria’s civil war began, the eyes of the world have shifted away from the country. No political solution is in sight. But while the European Union and its member states have turned their attention to other problems, there is no such luxury for Syrian refugees and the countries to which they have fled. Now numbering 5.4 million people in total, the vast majority of Syrian refugees remain stuck in Turkey, Lebanon, and Jordan. Economic strife, political turmoil, and resource scarcity in these countries have generated “crises within crises”, whereby global food supply shortages caused by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine dramatically contribute to inflation-related pressures that can aggravate existing inequalities [1].

Turkey, Lebanon, and Jordan initially showed generosity towards Syrians escaping Bashar al-Assad. However, security and economic conditions in Syria remain dire, meaning there is little to no prospect of large numbers of people going back. Repeated UN studies have found that most, and growing numbers of, Syrian refugees want to remain where they are for the time being. This is a position that most European states claim to support; yet the situation in the three key host countries is becoming ever more strained. Driven by intensifying domestic pressures, populations and governments in these countries are increasingly turning on Syrian refugees, blaming them for domestic problems and calling for them to leave.

Europeans might feel that now is not the moment to focus their attention on Syrian refugees, and indeed that they lack the capacity to do so. European governments largely now view Syria, including its refugee dimension, as a containable situation; only a comparative trickle of Syrians are still trying to enter the EU. The bloc’s policy of channelling still-significant levels of funding to Turkey, Lebanon, and Jordan remains in place and many EU and member state officials suggest there is little need to change course.

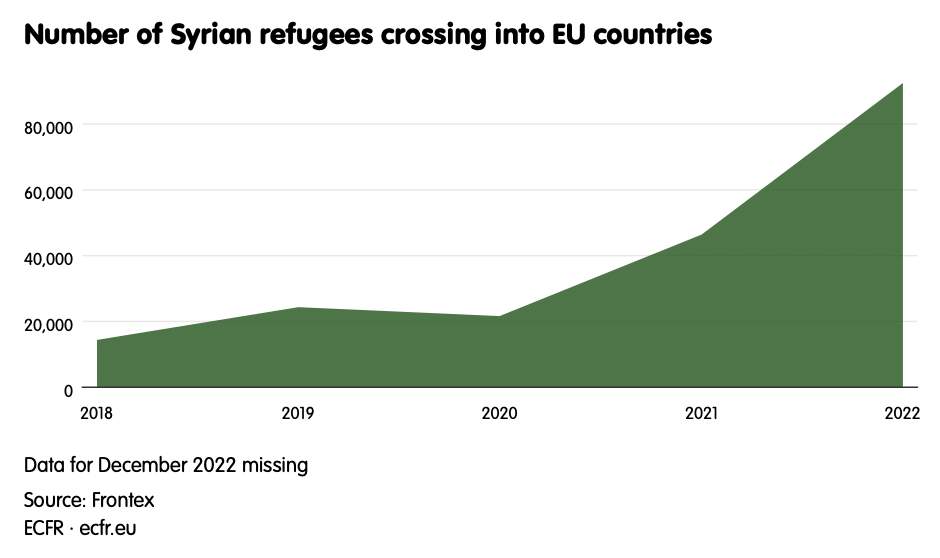

But policymakers in the EU would be wise not to look away too quickly. Host countries’ ability to meet refugees’ needs and keep the situation stable, including in terms of blocking the onward movement of refugees to Europe – their part of the deal in exchange for European financial support – is already severely exposed. Economic difficulties, rising political and social hostility, and inadequate support are likely to push up the numbers of Syrian refugees (and also in particular of Lebanese citizens) renewing their efforts to enter Europe. This would almost certainly be augmented by new outflows from Syria itself if any of these countries lose the capacity to manage their borders. While figures remain small compared to those of Ukrainians, in 2022 there was already a significant increase in the number of Syrians travelling to Europe. According to Frontex, in 2022, at least 92,000 Syrian refugees crossed into Europe – representing almost one-third of all irregular migrants recorded and up from 46,000 crossings by Syrians the year before.

To date, European support has largely focused on meeting short-term humanitarian needs. It has not made a systematic effort to provide Syrians with adequate access to economic livelihoods and rights or legal and human rights protections. Host governments have largely prevented Syrians from receiving these out of fear of prolonging their stay or even making it permanent. However, such elements can create the conditions for a more sustainable refugee presence, whereby Syrian refugees are able to access basic services, education, and employment opportunities. This approach can also help Syrians prepare (once their home country is truly safe) to travel back and be able to remain in Syria.

To address this, Europeans do not necessarily need to send more money – something that is clearly not on the cards given wider global priorities – but they should change how they deploy their support. This policy brief argues for Europeans to transition away from the predominantly humanitarian-led approach they have followed until now. Instead, they should pursue more durable solutions, such as promoting the inclusion of Syrians into local economies and ensuring they can access more rights. Alongside this, Europeans should take stronger account of the acute needs of host populations. This new approach will help Syrian refugees live more fulfilled lives and reduce their motivation to reach European shores. In this way, Europeans will also help host populations in Turkey, Lebanon, and Jordan access stronger public services as well as better education, training, and employment opportunities.

Something changed

The Syria crisis may appear to have settled into a sort of stasis; for the moment, there is no prospect of large numbers of Syrians returning.Nevertheless, the situation remains dynamic: domestic pressures, and with them political pressures, are building around the issue of Syrians’ presence in host countries at a time when international funding support is falling. Some governments are working to drive refugees out, including by deporting them to Syria. Syrians are also making the choice to leave the increasingly inhospitable environment in host states and travel to Europe for a life where they can access jobs, education, and healthcare on a sustainable basis. They are doing so in growing numbers.

Rising insecurity and its consequences

According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees(UNHCR), Jordan hosts 660,892 Syrian refugees, Lebanon 814,715, and Turkey 3.5 million. Lebanon and Jordan have the highest shares of refugees per capita in the world: refugees make up nearly 20 per cent of Lebanon’s total population and more than 10 per cent of Jordan’s. Globally, Turkey has taken in more refugees than any other country since 2011, and 5 per cent of its population are now refugees, nine in ten of whom are Syrian.

It is worth noting that these numbers reflect refugees registered under the UNHCR, but in Lebanon the real numbers will be higher, since the government stopped registrations in 2015. At the same time, in their broader communications host countries tend to exaggerate the numbers for political reasons, to create a sense of urgency with donors and domestic audiences and, lately, to antagonise local populations against refugees and scapegoat them. For instance, Turkey claims to host 6 million Syrian refugees, Lebanon claims 1.5 million or sometimes even 2 million, and Jordan 1.3 million. Turkey has also strongly inflated its reported number of Syrians who have returned, citing a figure – 550,000 – it claims has gone to areas of Syria under its control. This is much higher than recorded returns from Turkey, which stand at around 158,000.

Initially, these countries’ governments and their populations welcomed fleeing Syrians in the expectation that their stay would be temporary. But more than a decade since the conflict began, UN surveys confirmthat Syrian refugees do not want to leave because of the ongoing security and economic situation in their home country. Some of those who returned to Syria have since gone back to host countries.[2] UNHCR figures show that 50,966 Syrian refugees voluntarily returned in 2022 and overall just 311,176 have done so since 2014. Only a small number of Syrians are now voluntarily heading back.

Domestic pressures in host countries

Since the refugees arrived, domestic pressures in Turkey, Lebanon, and Jordan have grown considerably. This is largely as a result of other factors, although Syrians’ presence in host countries still represents a cost to governments and, crucially, is a factor that some among local populations suspect of increasing the problems they face. The aftermath of covid-19, the impacts of climate change, and spillover from the war in Ukraine are all negatively affecting the availability of resources such as wheat.

Turkey and Lebanon in particular featured among the main recipients of Ukrainian wheat prior to Russia’s invasion and were among the top three countries in terms of the highest rate of food price inflation between February and March 2022. In Turkey, inflation reached an all-time high of 99 per cent. As one Turkish expert put it: “all of the challenges of the Ukraine war descended on us,”[3] pointing to the difficulty of securing grain following the Russian invasion. A recent survey found that around 75 per cent of Turks are concerned about access to food. Before the war, Jordan was also high on the list of Ukrainian food recipients, and government officials there worry about the consequences of grain shortages. Amman is increasing its reservesas a result.

Lebanon is at risk of becoming a failed state. The Ukraine conflict came after 85 per cent of Lebanon’s grain reserves was lost in 2020 during the blast in Beirut of 4 August that year, a tragedy arguably attributable to the country’s corruption and mismanagement. Local analysts joke bitterly that they have run out of ways to describe the total collapse in their country. The Lebanese pound has lost 90 per cent of its value and living costs have increased by 600 per cent, pushing most people below the poverty line. The Lebanese financial crisis of the last few years has seen between a third and half of all direct UN cash aid in the country swallowed up by Lebanese banks, resulting in refugees and others in need missing out on much-needed international assistance.

Turkey’s economy is also undergoing a significant slowdown attributable to high commodity prices and the impacts of global inflation. More than two-thirds of people in Turkey are having difficulty affording food and rent. The human cost of this economic decline is making itself felt. For example, more young people are dropping out of school and are struggling to afford ordinary necessities. More than halfof students in Turkey face malnutrition and most families live on the minimum monthly wage of no more than $295.

Jordan’s economy grew in 2022, but the pandemic nevertheless increased vulnerabilities among its population, and the government is dealing with a range of tensions and frustrations. Jordan’s real GDP per capita has been in decline since 2009 and the country needs structural reform. Despite the recent recovery, aided by IMF support, national debt is on the rise and the country continues to run a budgetary deficit. As a result, unemployment remains alarmingly high, especially among young people, half of whom lack access to jobs.

The economic conditions of recent years have therefore heightened the risk of rising social unrest in all three host countries.

The widening support gap

Following the initial arrival of the Syrian refugees, host governments began to seek international support to help sustain their presence. Turkey in particular used the threat of refugee flows to Europe to secure financial help, in 2016 striking a deal with the EU for €6 billion over four years. The EU approved an additional €3 billion for 2021-2024.

Similarly, Lebanon is currently asking for $3.2 billion under the Lebanon Crisis Response Plan, a mechanism set up to address the needs of the most vulnerable, and through which the country has already received $9 billion since 2015. Elections in May 2022 in Lebanon saw winning candidates ramping up pledges to enforce more restrictions on Syrian refugees.[4]

Jordan positions itself as a key ally to Western states when it comes to supporting Syrian refugees. But this very much depends on the ability of the EU, its member states, and the rest of the international community to ensure funding for the Jordan Response Plan, the key instrument for Amman to manage the presence of refugees.

Absorbing Syrian refugees since the beginning of the war has reportedly cost Turkey $40 billion – equivalent to 5 per cent of its GDP; Jordan has spent $10 billion and Lebanon $25 billion. By comparison, Europeans have contributed more than $10 billion to supporting Syrian refugees in key host countries. Germany is the second largest donor to the Syrian Refugee Regional Resilience Plan (3RP), a key humanitarian mechanism coordinating the international response to the Syrian refugee crisis in the region which contributed some $3 billion to host countries between 2015 and 2021. (The United States is the largest donor to 3RP overall with more than $5 billion; the EU disbursed around $1.8 billion.)

Yet the financial gap between what the international community is providing and what host countries require is widening year by year. This adds to the domestic strain in host countries and a sense there that the EU is not properly funding the gatekeeping role they are effectively carrying out for the Europeans. The 2022 Conference on Supporting the Future of Syria and the Region (an annual event since 2016) secured higher levels of funding than observers might have expected. But the $6.7 billion pledged still fell short of the UN target of $10.5 billion. Moreover, only 42 per cent of this support has materialised to date, with key long-standing donors such as the United Kingdom slashing their financial support for Syria by 67 per cent. This comes at a time when the United Nations’ wider humanitarian response is experiencing record funding gaps. Only 29 per cent of the funding for the 3RP was met for 2022.

From this year, the UN has cut monthly financial assistance from 90 per cent to around 77 per cent of the Syrian refugee population in Lebanon. The World Food Programme recently announced a one-third cut to food stipends to 353,000 refugees in Jordan (mostly Syrian), partly due to the war in Ukraine and other “competing requirements”. Financial support for the Jordan Response Plan has decreased by more than 50 per cent over the past four years.[5] During a visit to the region in September 2022 by UNHCR chief Filippo Grandi, Jordan’s foreign minister, Ayman Safadi, expressed concern over refugee response funding levels and reiterated the need for sustained international support. While funding under the EU-Turkey arrangements remains (for now), the broader picture is unsettled. For example, in Turkey, NGO Josoor recently shut down due a lack of funding and the worsening political climate.

Local tensions

Anti-refugee rhetoric is increasing among host populations, who accuse Syrians of being a drain on resources. In Lebanon, the public is dividedbetween those who blame corruption for the country’s problems and those who point the finger at the arrivals. Syrian refugees did not feature as heavily in campaigning for last year’s Lebanese general election as they did in 2018’s poll.[6] However, even some new, more reformist members of parliament who were part of the 2019 protest movement are hostile to Syrian refugees. Before the election, both Syrian and Palestinian refugees were barred by the Lebanese government from leaving their homes. In 2022, anti-Syrian hashtags trended, such as “our land is not for the displaced Syrian” and “no to the Syrian in Lebanon”. Local news sites report a rise in anti-refugee sentiment and hundreds of fights at bakeries between Lebanese and Syrians in the competition for bread. This is largely a result of the deteriorating economic situation and increased scapegoating of Syrian refugees, both in general and in the lead-up to the May 2022 elections.

With elections due this year in Turkey, hostile rhetoric about Syrian refugees is common and comes from right across the political spectrum. For example, leaders from the Republican People’s Party (CHP), the main opposition party to President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s Justice and Development Party, have declared that, if elected, their government would remove all Syrians within two years. The nationalist opposition party, Victory, has gone so far as to commission a 9-minute, anti-Syrian refugee short film, launched a “Send them back immediately” campaign, and is raising funds to buy bus tickets to send Syrians back. It has warned that Turkey is “becoming a Middle Eastern country”.

This campaigning has resulted in grave hate crimes towards Syrians. In 2021, a Turkish man set fire to three young Syrian men. In January 2022, a Syrian refugee was murdered in Istanbul. A UN report foundthat Syrian refugees in Turkey feel increasingly insecure in their neighbourhoods, are afraid to speak Arabic in public, and their children report increased levels of bullying in school. In the aftermath of the deadly explosion in Istanbul in November 2022, the word “Suriyeli” (“Syrians” in Turkish) trended on social media. Such dynamics are likely to intensify ahead of the elections and potentially in their wake too as the new government begins to implement its policy on Syrian refugees. A recent survey confirms worsening attitudes towards Syrian refugees in Turkey, with 82 per cent of people saying they want Syrians to return home.

Attitudes towards Syrians in Jordan are in fact positive overall, but studies indicate that Jordanians feel there is a negative economic impact from Syrian refugees. Some in local populations hosting refugees are starting to blame Syrians for their purported impact on state infrastructure and resources, especially water.[7]

Support for the presence of Syrian refugees in Jordan is likely related to maintaining current levels of international assistance.[8] For instance, Jordan allowed most Syrian refugees to be vaccinated due to regular flows of covid-related funding. But the harsh treatment received by non-Syrian refugees in Jordan is a harbinger of what Syrians can expect if aid flows slow down. Besides Syrians (and Palestinian refugees registered under the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East), Jordan also hosts refugees from countries that include Iraq, Yemen, Sudan, and Somalia. Yet, at least so far, very few donors are funding non-Syrian refugees in the country and availability is declining by the year. While all refugees in Jordan face restrictions on their rights, this is particularly pronounced for non-Syrians. These refugees are also far more likely to face deportation. If funding for the Syria refugee response were to decrease, Syrian refugees risk becoming subject to similar exclusions.

While not everyone in local communities is hostile towards Syrians, tensions are simmering. In Jordan, parts of the population, especially those in rural areas, argue that Syrians have access to English classes taught by native speakers while Jordanian children do not.[9] Syrian refugees in Lebanon are accused by those in the most affected host communities of receiving aid in US dollars while locals receive their salary in Lebanese pounds. The sectarian nature of the political system in Lebanon, where the permanence of a mainly Sunni Syrian population could tip the political balance against other groups, and the country’s complex history with Syria, have further worsened the problem. Permanently integrating hundreds of thousands of Syrians in Lebanon’s political system could upend politics in the country. Lebanese politicians go as far as to argue that a protracted presence of Syrian refugees would violate the constitution. Lebanon and Jordan have both experienced the case of Palestinian refugees, whose presence has become protracted in these countries – an outcome that the Lebanese government in particular resisted. “Lebanon doesn’t want another UNRWA,”[10]commented one European official.

*

In a region facing unprecedented challenges and increasingly hostile global and regional contexts, and where current solutions are characterised by short-termism, the picture is bleak for Syrian refugees. Current pressures could exacerbate the difficult, yet just about still manageable, status quo. This is especially the case if host governments continue to respond to citizens’ concerns by tightening the screw on Syrians’ everyday existence.

Politicisation of returns

Host governments are increasingly working to enable – and even force – returns in response to domestic public pressure and to divert attention away from their own economic and political failures. This has partly been stimulated by European and UN positionings, with a small number of the former now saying some parts of Syria are safe for returns and the latter undertaking increased work to facilitate those who are already choosing to move back.

Experts on the region suggest that such moves have helped shape a “disastrous” new environment for Syrian refugees – the shifts “started everything”,[11] said one. They argue these moves have emboldened governments to return more Syrians – something that was previously not happening – or at least pledge to do so. Another close observer said, “regional leaders look at [Europe] and think: ‘If they are kicking out refugees, why shouldn’t we?’”[12]

The recent fate of Syrians has varied from country to country, but pressure has increased in all three main host countries.

Turkey

In March 2022, the Turkish foreign minister and his Jordanian counterpart jointly agreed to cooperate on the “voluntary” return of Syrian refugees, announcing a conference on this issue (which has not yet materialised). Since early 2022, Turkey has stopped accepting applications for temporary and international protection in 16 provinces and limited residency permit applications to neighbourhoods in which foreigners do not exceed 25 per cent of the population. The Turkish authorities have also turned away Syrians trying to enter the country (saying that the camps are full) and rejected undocumented refugees — which is against international protection standards. Even when Syrian refugees can register in theory, local authorities unofficially discouragethem from doing so.

In May, Erdogan announced that Turkey would ‘return’ a million Syrian refugees to those parts of northern Syria under its control, where there is a security and governance vacuum. It is an overpopulated area without any clear functioning authority or an economy that offers viable job prospects. Construction projects funded by Turkish companies do not include the public infrastructure needed to host large numbers of people, such as hospitals and schools.

As noted, this year’s elections in Turkey could lead to closer government engagement with the Assad regime and translate into more serious attempts to return Syrians. Kemal Kilicdaroglu, the head of the CHP, has said he would make a deal with Assad on returns. He also announced a four-part plan, which, he claimed, the EU will fund. Across the board, Turkish politicians’ rhetoric is softer towards Assad than in the past. The Erdogan government’s recent outreach to Damascus risks putting Syrians in danger of being deported, regardless of the election results. And, in contradiction to the claims of Turkish officials, many Syrian refugees heading towards so-called safe zones through the Akcakale Border Gate, in the Urfa district, have told reporters that their return is not voluntary.

Lebanon

In June 2022 – on World Refugee Day, no less – the Lebanese government announced its Lebanon Return Plan. In July, the caretaker minister for displaced persons, Issam Charafeddine, stated that the country would formally negotiate refugee repatriation with Syria. This was followed in August by a joint statement by Lebanese and Syrian officials that “there is a consensus … regarding the return of all refugees.” President Michel Aoun also announced Lebanon’s intention to “file complaints in international forums” to deport Syrian refugees. Caretaker prime minister Najib Mikati declared that repatriating Syrian refugees will be a “priority during this period”.

Although the government announced it would send back 15,000 Syrian refugees a month, and indeed repatriations were set to begin at the end of September 2022, it put the plan on hold, where it remains. Nevertheless, repatriations started in October, following a revival of a previous initiative launched in 2018, in which the Lebanese General Security agency facilitates returns by putting Syrians who ‘voluntarily’ sign up onto buses that then take them to Syria. As part of this scheme, while 1,700 out of 2,400 refugees were allegedly given the green light by Syrian authorities to go back, in the end only 750 people decided to return. Some of these individuals were then arrested or disappeared.

Jordan

In Jordan, re-engagement with the Assad regime started in 2021 and mainly remains limited to security issues and trade. But, and especially in light of dwindling international funding and political attention, this dialogue may well result in increased cooperation between Jordan and Syria on refugee returns. This may not only increase the chances of forced returns, it also has the potential to influence public opinion through its implicit suggestion that Syria is now stable.

*

Host governments have lately worked to make life harder for Syrians, or even deport them. These actions are more serious than previous efforts (such as Russia’s 2019 proposals to implement its own refugee return plan). This shift has come about because of today’s greater societal tensions and worsened economic situation, and together they make Turkey, Lebanon, and Jordan increasingly unwelcoming places for Syrians.

Reasons to leave

Rather than being forcibly returned, the many Syrians unwilling to go home are likely to make new attempts to reach Europe.

In 2022, the number Syrians trying to cross into Europe doubled in comparison with the previous year. The UNHCR says that the number of people who tried to leave Lebanon by sea rose by more than 70 per centlast year.

The desire to leave is confirmed by, for example, a recent poll that revealed at least 69 per cent of Syrian refugee respondents are planning to leave Lebanon for a third country – a 42 per cent surge in two years. In September 2022, a migrant boat sailing to Europe from Miniyeh, near the Lebanese city of Tripoli, sank off the Syrian coast, causing the tragic death of 94 people. This was the deadliest voyage of its kind from Lebanon. These trends continue: on 1 January 2023, a Syrian woman and child perished aboard a vessel leaving Lebanon carrying more than 200 people, mostly from Syria and Lebanon. Instead of being granted safety in Europe as they wanted, rescued refugees were instead forcibly returned to Syria.

According to reports, the Greek authorities have pushed back more than 52,000 people from Greek islands into Turkish waters since 2016, but half of these – around 26,000 – were pushed back in 2022 alone. In just the first week of 2023, the Greek coast guard stopped 32 boats carrying 1,108 people, marking a 125 per cent rise in pushbacks compared to the first week of 2022. Syrians are among the key groups within this number. At least 25,000 Syrians recently left Turkey for the EU. In September, a group of Syrian refugees was reported to be planning a caravan to the EU.

For the moment these numbers are manageable, with Europeans by and large able to control their borders, though at a great human cost. In all likelihood, host countries looking to secure more European financial support, and generate urgency among domestic audiences, are more or less deliberately taking steps to increase these numbers; or, at least, to create a situation in which they can play to domestic audiences while generating new leverage with EU states.

Nevertheless, Syrian refugees in host countries face legal, bureaucratic, and financial barriers to education, employment, and participation in economic life. Registrations in Lebanon, Turkey, and Jordan have either been banned or made challenging due to inconsistencies and high fees. In Lebanon, over 80 per cent of Syrian refugees have no legal residency documentation, which is essential to access employment, education, and basic services, and to exercise freedom of movement. Only 16 per cent of Syrians over the age of 15 hold legal residency in Lebanon. In Jordan, Syrian refugees are barred from key employment sectors such as medicine, education, and engineering, which means that many engage in informal work, something which increases local populations’ negative perceptions. Legal restrictions by the Turkish government create barriers to freedom of movement that harm Syrians’ prospects of securing a steady income. Many Syrians are not registered as refugees. The vast majority live outside refugee camps. They are subject to abuses and discriminatory practices by host country authorities, such as discretionary security checks, evictions, random arrests, and deportations. As a result of these difficulties, more than 70 per cent of Syrian refugees live in poverty.

Syrian refugees thus live in a state of great precarity, unlikely to be able to return safely any time soon and stuck receiving only short-term support. Their current predicament also means they put pressure on host countries’ economies, infrastructure, and services such as education, health, electricity, and water. Without legal papers that allow them to exercise basic rights, such as the freedom of movement that would allow them to move around to find work, Syrians are denied access to many services and end up reliant on aid support. If they were provided with adequate identification and work permits, Syrian refugees would be able to play a more productive role in the societies that host them. Currently, their limited ability to contribute to host countries’ economies, as well as their overall isolation from wider society, often forces them to undertake illegal work and pushes children into illegal pathways, such as forced labour. This not only has extremely negative consequences for the lives of Syrian refugees themselves, but ultimately is also detrimental for host countries.

A new approach

With hostility growing among host states’ political leaders and populations, Europeans should acknowledge the real possibility of a continued rise in the number of Syrians travelling west. In response, policymakers should focus on reshaping the support Syrians receive in host countries. They should aim to demonstrate how a more inclusive approach can benefit both refugees and local populations.

Europeans have invested hugely in supporting Syrian refugees in the region and beyond. Having paid out a total of €27.4 billion since 2011, the EU’s Syria response is among the longest-standing and best-funded in the world. But this support has been predominantly of a humanitarian nature, such as providing food and access to basic services. This approach dates back to the requirement to support refugees’ immediate needs on the ground as the violence developed. But it also reflects a political focus adopted by Europeans on supporting eventual returns: namely, that it is reasonable to support Syrians in their temporary situations in host countries because – at some unspecified point in the near future – they would undoubtedly return to Syria.

However, this strategic choice has strung Syrians along, denying them the possibility of achieving sustainable existences. They are unable to secure meaningful economic livelihoods or obtain legal rights. The result has been that Syrian refugees remain dependent on day-to-day humanitarian support.

Indeed, NGO representatives describe European aid as unreliable due its short-term humanitarian nature, which does not allow for effective programming.[13] They also highlight the effect of cuts in wider international aid and describe the constant need to adjust the lens of their work according to shifting funding priorities, such as gender, climate, and food security – donors earmark new funding not specifically for Syrian refugees but rather tie it to these wider priorities. This prevents NGOs from finding the appropriate balance between meeting the short-term needs of refugees and equipping them with the resources and rights they need to be self-reliant and establish sustainable existences.

A core plank of Europeans’ revised approach should therefore be to alter the type of support they either provide directly or fund in host countries. They should shift from a short-term, humanitarian approach to one that, admittedly, stops short of integrating Syrians but provides greater inclusion through ensuring stronger access to jobs, education, and health services. Europeans can do this by showing host countries that their own populations can also benefit from refocused European investment in employment and public services. Delivered successfully, this new approach could even support Syrians in ways that will smooth eventual returns rather than impede them.

This approach would pair humanitarian support with measures that systematically increase Syrian refugees’ access to training and jobs, and wider protection rights. One World Bank study recommends improving the well-being of refugees and their hosts, instead of focusing on returns “at any cost”, as the authors describe it. Indeed, it finds that the same factors that empower refugees in host countries – and that host governments often perceive as integration, such as access to education and employment – equip refugees with the tools that make voluntary returns sustainable. Such an approach would provide them with the ability to be economically independent, able to accumulate assets, and gain technical skills they can use upon their return to Syria.

A challenge for European policymakers is that this revised approach would quickly run into opposition from these countries’ governments, and potentially societies too, as it implicitly acknowledges a prolonged stay for Syrians. Europeans may also have to make this shift at a highly inopportune moment – if they had done so several years ago then circumstances would have been more favourable, with host governments contending with fewer stresses and strains. But the fact that these pressures are only likely to continue to increase means Europeans should act sooner rather than later to convince host countries of the value of switching focus.

In some cases, Europeans have already started to adopt more of a long-term focus under the operational framework known as the “triple nexus”. This involves identifying areas where short-term, humanitarian needs can be integrated with development and security, as well as programmes that ensure Syrians can access physical and legal protections and rights, and live in safety and dignity.

Jordan’s government and its cooperation with the UN and NGOs is particularly advanced in this regard, with Europeans helping communities build capacity both at the national and the local level. Education is a key example. The Jordanian government has taken notable steps towards integrating Syrian refugees in schools and other educational facilities, following the Jordan Compact, an agreement that stemmed from the 2016 London Syria conference. The compact pledged to boost trade with the EU in exchange for more integration of Syrian refugees. Another key document is the Education Strategic Plan, the government’s strategy to improve education for everyone in the country. This has improved access to education for Syrian refugees and helped local bodies better cater for their presence. However, despite significant government investment, Jordan still invests less money in education compared to Tunisia, Egypt, and Morocco, and the sector remains weak. Without additional necessary reforms, such as ensuring Syrian children are enrolled in early childhood education, it will not be possible to say that Jordan is adequately addressing this need.

Overall, European programmes under the triple nexus framework remain rare and limited in ambition. As one UN official put it, there has been “a lot of talk, very few examples”[14] of its application. To cite education again, despite significant European expenditure on this via its wider humanitarian support, activity in the area is narrow in scope and lacks clear timelines.[15] For instance, education initiatives targeting Syrian refugees in Lebanon are mainly supported through humanitarian EU funding. This results in limitations deriving from the annual (as opposed to multi-year) budget structure of the European humanitarian and emergency response and the nature of the support this can enable. While it may allow the rapid deployment of emergency and humanitarian mechanisms, their short-term nature creates uncertainty about the funding available each year, which can change in scope and size depending on EU decision-makers’ wider priorities. This increases the unreliability of medium-term commitments and narrows the scope for strategic planning for comprehensive and much-needed reforms.[16]

Another obstacle is the closure of the EU Regional Trust Fund in response to the Syrian crisis (also called the Madad Fund). Many EU officials and civil society actors in the region viewed this facility as critical for supporting Syrians in the region and “a textbook case of a nexus approach” due to the long-term nature of the projects that it covered, such as access to local infrastructure, improved basic services, and awareness-raising campaigns.[17] Remaining Madad Fund support for 2024 and 2025 is limited, mostly part of its exit grants.[18] When asked about the gaps caused by the fund’s closure, European officials emphasise that the same levels of commitment remain at least for the next two years, either integrated in other European Commission funding (under the new Neighbourhood, Development and International Cooperation Instrument) or as part of wider cooperation with host countries in the region.[19] For instance, one EU official pointed to new funding to tackle the regional food crisis, which will include Syrian refugees.[20] However, this will lack a nexus dimension even though it encompasses local communities.

Crucially, much of this sort of support does not address structural issues such as those affecting Lebanon’s education system (for example, large class sizes, lack of electricity or internet, and discrimination by education officials in charge of admitting refugees to schools). Education is particularly viable as a domain where more support for host countries could also benefit host populations, and perhaps be less controversial than giving Syrian refugees more permanent forms of stay. Some of the policy building blocks are in existence. For instance, Lebanon’s Five-Year General Education Plan, approved by the Ministry of Education in 2021, states that education should be provided to everyone regardless of their nationality. But observers warn that “insufficient funds” dedicated to the plan risk leaving thousands of students (Lebanese, Syrian, and others) with inadequate education.

A further issue is that of ensuring protection for refugees – namely, that Syrians can exercise their rights, access basic services, and have their presence in host countries and refugee status documented. Directing European investment towards these issues could pay dividends in the long term. Refugees need to have legal documents to be able to access healthcare, employment, and services and mitigate the risk of deportation. There is great scope for support by the EU and its member states on this front and, according to local experts, this remains an underexplored area.[21]

However, access to rights and services is a controversial topic for host governments, which fear providing these will lead to Syrians remaining permanently. Bringing governments round to the need to improve Syrians’ legal status will require significant political investment on the part of Europeans, who have long resisted pressing this case. But rising pressures in host countries and the increasingly apparent inadequacy of their present approach should encourage Europeans to begin conversations with host states over how to support more sustainable, longer-term approaches to refugee integration. Indeed, given their position as leading financial supporters and proximity to the region, the EU and its member states, as well as the US, are uniquely placed to encourage key host countries to adopt greater inclusion towards Syrian refugees.

Recommendations

The great number of issues that face Europeans at home and across the world means that the plight of Syrian refugees has slipped down their agenda. But Russia’s war on Ukraine and the resulting refugee crisis, severe inflation, and the post-pandemic recovery also mean that Europeans have a clear interest in minimising instability originating from their southern neighbourhood. Even with less money to go around, as will likely be the case for some time to come, Europeans need to devote political attention to ensuring that, at a minimum, current funding levels go the extra mile to support regional stability and create the necessary conditions for a sustainable refugee presence. They can achieve this by moving to a strategy that enables inclusion for Syrian refugees in host countries rather than delivering only short-term humanitarian support.

Most Syrian refugees are unwilling to return in the near future – a position supported by the EU and key member states, whose stance largely remains that Syria is still not safe for them. Even if Assad were suddenly to depart the scene, experts estimate that it would take 20 years to go back to normal conditions in Syria. In this context, the best way to meet European interests is to invest in sustainable longer-term approaches to refugee support in key host countries. Alongside better supporting Syrians and relieving economic and social pressures in host countries, it will help avert a scenario whereby increased numbers of Syrian refugees begin to enter Europe.

To achieve this, Europeans should identify new ways to equip Syrians with the means to become self-reliant, meaning they can make an income without relying on government support or international aid, such as cash assistance. Access to education and economic opportunities are central to this. Providing these will in turn depend on Syrians being able to access wider legal protections in host countries to receive security and guarantee basic rights. Critically, European assistance in host countries needs to also boost support that benefits local populations. This can include education reform and job creation, given the immense hardships communities face and the resentment fuelled by the sense that refugees are receiving help not also offered to them.

Concretely, decision-makers in the EU, member states, and relevant international agencies should consider the following actions.

Reshape the offer

To mitigate negative reactions by host governments, Europeans should talk about “inclusion” rather than “integration”. Experts describe inclusion as the “new word” and a “big game changer”.[22] For their part, host countries have shown willingness to accept development initiatives that involve a certain level of inclusion without integration if it comes with adequate development funding.[23] The example of Jordan’s integration of Syrian refugees into its national education plan, while imperfect, is proof that host governments are willing to include Syrian refugees when they receive sufficient assistance. Europeans could offer incentives to help strengthen host countries’ wider education systems and to ensure that employment and opportunities to increase skills are also directly tied to strengthening local economies. As they approach governments – for instance, during preparatory conversations in the lead-up to this year’s Syria conference – Europeans and other international donors such as the US should deploy the significant leverage of their aid support.

Amplify the message

Host governments’ rising hostility towards Syrian refugees means that Europeans will need to undertake significant political engagement if they are to successfully deliver a new strategy. Together with NGOs and other experts, they should devise a common, clear language on key issues regarding Syrian refugees and speak in a unified way about the daily pressures Syrians are facing.[24] Currently, and despite limitations in the present approach, there is strong synergy between the UN and the EU and its member states that could amplify this message: besides being an essential implementing partner for the regional Syrian refugee response, the UN is a key player when it comes to expressing international solidarity with host countries. It relies heavily on European support to ensure host governments do not obstruct its activities and those of its NGO partners. However, a high-level UN official admitted that cooperation is sometimes “tainted by individual member states’ behaviour”.[25] In addition, Europeans could attach a deadline for the enhancement of protections and legal guarantees, such as the issuing of residency papers by government authorities, ensuring that these are regularly reviewed and renewed as necessary.

Emphasise the importance of “successful returns”

In their conversations with governments in the region, the EU, member states, and other international actors such as UN officials should emphasise the importance of “successful returns”.[26] They should warn of the problems posed by refugees “re-returning” because they were pushed out (or even deported) prematurely, ill-equipped to rebuild their lives in Syria. Offering Syrians the economic tools and protections necessary to remain in Syria once they decide to return should prove attractive to host countries. Continued “re-returns” risk angering local communities as they become aware of Syrians coming back.

To assist in this, Europeans should hold to the line that Syria remains unsafe for returns. Those European states that are changing position on this should bear in mind that such rhetoric will only help host countries do likewise. The result could be not only more forced returns, and thereby more “re-returns”, but also more Syrian refugees seeking to get to Europe – thereby exacerbating the very challenge that these European states are trying to avoid.

Highlight the long-term nature of the issue

While host governments’ public rhetoric might be strongly anti-refugee, they will nonetheless likely accept the basic notion that many Syrians are set to stay in the medium term and therefore ought to receive a degree of support, if only for the sake of their own domestic stability. Based on the current rate of returns of Syrian refugees from Lebanon, it would take 54 years for all Syrians in the country to go back.[27] Given this reality, the EU, its member states, and US and UN representatives should point out that host governments would be better served by providing refugees with greater access to legal documentation, rights, and economic opportunities, even if on a temporary basis.

Work with local civil society organisations

Local civil society organisations have shown they have the ability and tools to effectively advocate with their own governments. They have had success in increasing refugees’ access to legal guarantees and navigating bureaucratic hurdles. For instance, Lebanese NGOs were instrumental in ensuring direct assistance following the Beirut blast, playing a key role in disaster relief. Such actors can help international donors overcome the structural barriers in host countries, such as bureaucratic obstacles, that reduce the impact of financial support. Europeans should capitalise more on those organisations’ experience and knowledge.

At the local level, Europeans are already aware of the need to support social cohesion initiatives, but they should help scale these up. The number of people in host communities impacted by the Syria refugee crisis is almost as high as the number of Syrians registered in these countries, and they deserve considerable attention. Again, Europeans could work with local civil society organisations to encourage positive engagement between communities and Syrian refugees – including through ‘win-win’ economic links, for instance by providing training that assists both refugees and locals. Europeans could also work with local civil society groups to devise advocacy strategies that debunk common myths related to Syrian refugees among local populations. These should emphasise that Syrians themselves wish to go home and that, if provided with adequate access and legal status, they can be an asset to the economy rather than a spoiler.

Seize the opportunity of the 2023 Brussels conference

This year’s Brussels conference provides an opportunity for Europeans to shape collective donor thinking, along with other key donors such as the US, the UN, and Syrian and international NGOs. They should focus this effort on drawing up sustainable, longer-term approaches to support for Syrian refugees. Europeans should work to ensure the conference addresses the need to help Syrian refugees in host countries become more self-reliant and that delegates understand what national and local systems need to be in place to achieve this goal. The EU and other donors should reinstate the Madad Fund and strengthen it. The fund should be able to support Syrian refugees’ specific needs, such as obtaining legal documentation, alongside those of other vulnerable people in host countries.

Resettle more refugees in Europe – even in small numbers

In return for these asks, Europeans could resettle more refugees than it currently does. They should start by meeting the targets set out in the EU’s agreement with Turkey, which they have failed to achieve. In 2022, Syrian refugees remained the largest population of refugees in the world in need of resettlement, and the projected number for 2023 – 777,800 – represents a 27 per cent increase compared to the previous year. Refugee experts suggest that resettlement can go a long way as a gesture of good will towards a host country.[28] They view this as a powerful instrument for diplomatic engagement and point out that taking in even small numbers of refugees can impact positively on the relationship with a host country. One official recalled how resettling just a couple of hundred refugees was received with great appreciation by a host country “as a friendly act” and a “concrete gesture of solidarity”.[29] Last December’s approval by the European Parliament and EU member states of the first-ever refugee resettlement framework, the fruit of a six-year-long effort, is a positive step in this direction, though still limited as it is voluntary and lacks fixed quotas.

Conclusion

The more Europeans cut support for Syrian refugees, the more trouble they will have in influencing the course of events in Turkey, Lebanon, and Jordan with regard to the refugees’ future. The EU and its member states have invested more than ten years of consistent support in this area. They should not shy away from highlighting this and should build on it. Europeans should reshape their strategy towards Syrian refugees to something more fitting for the longer term, in which Syrians appear set to remain away from home for a prolonged period.

If matters continue to deteriorate, Europeans will find their leverage weakened and face large numbers of new arrivals of Syrian refugees. A revised approach to supporting Syrian refugees in Turkey, Lebanon, and Jordan will provide a more sustainable way forward – one that promotes stability within these countries and gives Syrians residing there greater dignity and opportunity.

About the author: Kelly Petillo is the coordinator for the Middle East and North Africa programme at the European Council on Foreign Relations.

Source: This article was published by European Council on Foreign Relations.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank all the experts, policymakers, and friends in the Middle East, Europe, and beyond who provided their input for this paper. Heartfelt thanks also go to those ECFR colleagues whose help was essential in shaping the publication, especially Julien Barnes-Dacey, Jeremy Shapiro, and Tarek Megerisi, but also those who provided much-needed moral support along the way, like Edin Dedovic and Kim Butson. Finally, thank you Adam Harrison for the thoughtful editing and patience.

ECFR would like to thank the foreign ministries of Denmark, Norway, and Sweden for their ongoing support for the Middle East and North Africa programme, which made this publication possible.

[1] Author’s interview with a Turkish expert, July 2022.

[2] Author’s interview with UN officials, June 2022.

[3] Author’s interview with a Turkish economist, July 2022.

[4] Statement by a Lebanese academic at an experts workshop, June 2022.

[5] Author’s interview with an EU official, August 2022.

[6] Author’s interview with a Lebanon-based journalist, June 2022.

[7] Author’s interview with a Jordanian representative of the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, June 2022.

[8] Author’s interview with a Jordanian expert, June 2022.

[9] Author’s interview with a Jordanian representative of the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, June 2022.

[10] Author’s interview with UK officials, June 2022.

[11] Author’s interview with a Syrian expert based in the region, June 2022.

[12] Remarks by an expert at a workshop on Syrian refugees, May 2022.

[13] Author’s interviews with international and regional NGO representatives, June-August 2022.

[14] Remarks by a UN official at a workshop on Syrian refugees, December 2022.

[15] Author’s interview with a Lebanese expert, July 2022.

[16] Author’s interview with an EU official, July 2022.

[17] Author’s interview with an EU official, July 2022.

[18] Author’s interview with an EU official, July 2022.

[19] Author’s interview with an EU official, July 2022.

[20] Author’s interview with an EU official, July 2022.

[21] Author’s multiple interviews with local experts in the region, June-August 2022.

[22] Remarks by UN official at a workshop on Syrian refugees, December 2022.

[23] Remarks by UN official at a workshop on Syrian refugees, December 2022.

[24] Author’s interview with UN representatives in Amman, June 2022.

[25] Remarks by a UN official at a workshop on Syria refugees, December 2022.

[26] Author’s interview with a World Bank expert, July 2022.

[27] Author’s calculation based on the official UNHCR number of 825,000 Syrian refugees. According to the UN, 76,600 Syrian refugees returned voluntarily from Lebanon between 2016 and 2022.

[28] Remarks by a UN official at a workshop on Syrian refugees, December 2022.

[29] Remarks by a UN official at a workshop on Syrian refugees, December 2022.