Of Georgian Personalities And Politics: European Dreams, National Elections And Future Days – Analysis

By Published by the Foreign Policy Research Institute

By Luis Navarro*

(FPRI) — Films are among the most visible demonstration of American soft power around the world. The impact of The Godfather, Scarface, and The Magnificent Seven on Georgia are among a few examples of movies that became part of the collective conscious of a nation. Almost all Georgian men, as well as many women, who came of age in the first decade following Georgia’s independence from the Soviet Union, are very familiar with them. Coming at a time when Georgia was struggling with a civil war in addition to rampant crime, corruption, and drug abuse in a failed state, a post-communist economic collapse, the paramilitary Mkhedrioni, and Georgian mobster “thieves in law.” Perhaps, the appeal of those films lay in appearing to romanticize their circumstances. The films’ narrative themes of a strong leader emerging to lead, usurp, or otherwise defeat powerful opponents and achieve success—only to face betrayal which forces these leaders to re-configure themselves in order to either triumph or succumb to fate—could be seen as reflections of the political landscape. The cautionary tales of early opposition leaders, like Merab Kostava and Gia Chanturia as well as former presidents Zviad Gamsukhurdia, Eduard Shevarnadze, and former Prime Minister Zurab Zhvania, may all serve to demonstrate the Georgian experience with the phrase that you either die a hero or live long enough to see yourself become the villain.

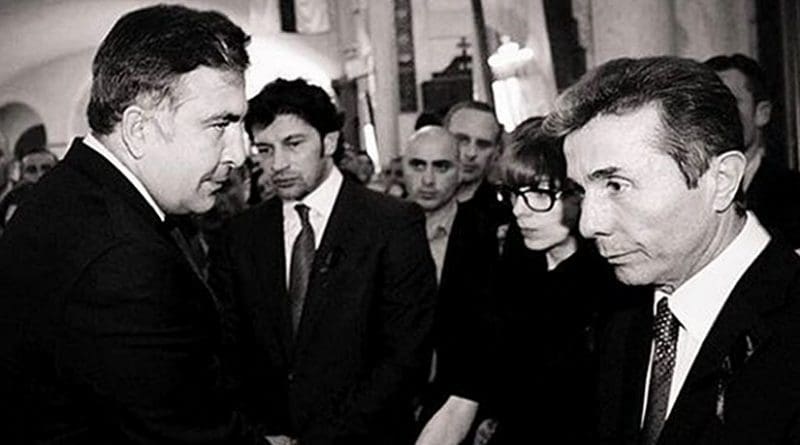

In the final days of the 2016 parliamentary elections in Georgia, what remains of Bidzina Ivanishvili’s original Georgian Dream (GD) coalition seeks to assert its claim as the only electoral bloc responsible for making Georgia the crown jewel in the rough and tumble region of the Caucasus and the only one capable of making progress towards formal European membership. The United National Movement (UNM) of Misha Saakashvili counters that not only did it establish this modern, functioning nation-state that emerged at the beginning of the 21st century, but also that the GD seeks to suppress competitive dissent and encourage cultural nativism, which will subvert the nation’s European trajectory in an effort to appease Russia. The 2016 Georgian parliamentary elections on October 8 will likely answer the question of which message will triumph and whether any new political force could emerge as either kingmaker or relevant opposition.

The irony of this election is that neither Ivanishvili nor Saakashvili hold any formal leadership role in either party, yet success or failure of their electoral vehicles will bear their imprimaturs. The indelible role of the billionaire oligarch, Ivanishvili, will continue to define the public perception of reality that, regardless of whoever from GD may hold the offices of Prime Minister, President, or Chairman of Parliament, Ivanishvili’s vision and will are determinative for their national objectives. Meanwhile, Saakashvili’s efforts and UNM’s inability to wage a campaign that isn’t much more than a referendum on his term of office, and his promised return to Georgia makes it all but impossible for them to redefine themselves in any meaningful way in the eyes of the voting public or to achieve a mandate beyond Saakashvili’s physical return, which could certainly be complicated by the fact that he is currently a wanted man in his country of origin, where he is no longer a citizen. The election environment will be judged against the electoral cage match of 2012 that preceded the nation’s first electoral transfer of power, but it is still noteworthy that the outcome may hinge on the winning party having to coalesce with others outside of their electoral bloc in order to govern. This election is dynamic despite GD advantages of incumbency, poorly monitored campaign financing, as well as prosecutorial tactics that suggest more reforms are necessary. But regardless of the outcome, can Georgia begin to transcend zero sum governance in its relationship not only with opposition political parties, but also with media and civil society outside of a partisan frame? Will the use of law enforcement as a political tool be discontinued? Can it surmount the trend in the West of right wing populism which is increasingly aligned with Russian interests? And what impact could any of these challenges pose to Georgia’s future?

Dreamscape

In a March 2016 poll conducted by the National Democratic Institute (NDI), two-thirds of Georgians believed that Bidzina Ivanishvili continued to be a decision maker in the actions of the government, and more than half did not think he should have a role in decision making, officially or otherwise. However, Ivanishvili seems to see himself as a latter day Cincinnatus and styles himself as something of a savior having defeated his nemesis, Saakashvili, in the 2012 parliamentary elections. This had been previously proven almost impossible, especially after failed street demonstrations in 2007, 2009, 2010 and 2011, as well as the 2008 electoral efforts by opposition parties and the Russian invasion. Ivanishvili stayed in office as PM for just the final year of Saakashvili’s presidential term: a so-called period of “cohabitation” with Saakashvili’s tenure the only problem Ivanishvili deemed worthy of his full attention since he resigned in the days between Saakashvili’s departure and the signing of the long sought national objective of an Association Agreement with the European Union in November 2013. Ivanishvili prefers to characterize his departure from office as a selfless act reflecting both his public announcement upon entering into politics and his since declared belief that people should not hold high office for long. His roles in the appointment of his longtime aide de camp, then 31 year-old Irakli Garibashvili, as his successor in 2013 and Ivanishvili’s subsequent replacement of Garibashvili in 2015 with the much more composed, experienced, technocrat and former economy minister, Giorgi Kvirikashvili, as Prime Minister, suggest that Ivanishvili never viewed holding office as necessary to exercising power. This belief is also borne out by Ivanishvili’s claims in recent years that he was the financial underwriter for all of the things he deems, but does not fully specify, as positive aspects of the Rose Revolution and to being more involved in the day-to-day governance advisory of Saakashvili’s regime through his re-election in 2008 than he currently is for Kvirikashvili. What is hard to reconcile with his comments—especially when one reads his October 2011 letter announcing his entry into politics wherein he explicitly lauds then-Minister of Internal Affairs (MIA) Vano Merabishvili for his ability and judgment—is that this would mean that beyond his claim of underwriting the reform of the street police under MIA, Ivanishvili was not moved to distance himself from the ruling UNM government due to concerns over its handling of the 2006 Sandro Girgvliani murder case, the November 2007 street demonstrations, or subsequent takeover of the late oligarch Badri Patarkatsishvili’s Imedi television station. All of these instances involved Vano Merabishvili directly and were criticized by international rights organizations and some Western governments. Instead, Ivanishvili says that it was Saakashvili’s 2008 re-election, which was deemed by many observers as problematic but legitimate, that led Ivanishvili to break with UNM. Perhaps Merabishvili’s refusal to follow Ivanishvili’s directive to secure Saakashvili’s resignation in 2011 contributed to his prosecution.

Since taking over parliament and the government in 2012, the GD has enjoyed significant success in moving the country towards greater integration with the West and has taken steps to reverse some of the most egregious excesses and failures from UNM’s rule from 2003 to 2012, such as halving the prison population through amnesty, beginning to reform the court system, and creating universal health insurance for Georgian citizens. But it has failed to live up to the economic expectations it set given the apocryphal legend of Bidzina Ivanishvili’s generosity to his village of Chorvila, where he is credited with providing a new house to everyone—except the teacher who criticized his school work and failed to acknowledge his potential. As the election approaches, Ivanishvili dominates the media and political landscape once again making clear repeatedly that “his project” is the only chance for Georgia to advance as a nation and that the largest opposition party not only opposes that advance, but also is an existential threat to the fair and peaceful conduct of these elections. This closing argument, part of the zero sum approach to politics that is deeply rooted in Georgia and has been on full display in the United States since 2010, is the narrative that Ivanishvili is pursuing in order to achieve a parliamentary super majority while he seeks to cement Georgia’s transition from one party rule under UNM in 2012 to one party rule under GD in 2016. As the richest man in Georgia, having pushed out his most reliably pro-Western coalition partners and allegedly the grey cardinal of the ruling party, neither he nor his party have given much indication as to what they would do if the voters confer that power upon them.

At a minimum, Ivanishvili’s wealth makes it hard to distinguish between his interests and those of the state. This year, when speaking to the United Nations, Prime Minister Kvirikashvili announced the construction of two new universities omitting that they would be financed not by the state but by Ivanishvili’s Cartu Bank. Ivanishvili’s Panorama Center will transform the landscape and view of downtown Tbilisi, a decision made by a local government agency, not the sakrebulo (city council) and without public input while dismissing demonstrations concerned about the environmental damage that the Panorama will allegedly do to Tbilisi’s landscape. “The Panama Papers” disclosure confirms Transparency International’s (TI) accusations regarding Ivanishvili’s offshore accounts while Prime Minister, allegedly in violation of law but apparently immune from investigation by law enforcement, and it opens the question of what role those accounts could have played in terms of Ivanishvili’s potential buyback of the Russian-based assets he claimed to sell during the 2012 election. While he has been extensively promoting the Georgian Dream in numerous recent press interviews, Ivanishvili seemed to imply that he may find it necessary to leave Georgia with his financial assets in what he and PM Kvirikashvili insist is the impossible scenario of a UNM victory—once again conflating his own wealth with the nation’s interest.

There are a number of actions that have taken place since 2013 that would serve to effectively counter the UNM argument that Ivanishvili was ever the agent of Russian President Vladimir Putin. Georgia is engaged in discussions around an EU free trade agreement. The Kremlin has publicly taken issue with the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) announcing the establishment of a military training center; Georgia remains engaged both in coordinated maneuver exercises and military missions with NATO and the EU. The increasingly likely prospect of a visa free regime further demonstrates that the GD government has moved forward on the consistent aspirations of a two-thirds majority of Georgian citizens who would like to see Georgia become a member of the NATO and the EU.

However, the GD government has experienced setbacks in its efforts to engage Russia in a less outspoken manner than its predecessor. Russia backs the independence of Georgia’s frozen conflict zones in Abkhazia and South Ossetia. Prior to GD’s arrival in government, Russia had already failed to withdraw to the Administrative Boundary Lines (ABL) in the post-August (2008) War agreement negotiated by former French President Nicholas Sarkozy. Since GD’s takeover, Russia has still continued to engage in the practice of “creeping occupation” by unilaterally moving the lines from the occupied territory of South Ossetia further into the region of Shida Kartli and drawing the border within meters of both the underground Baku–Tbilisi–Ceyhan gas pipeline and East-West (S1) highway. As was true under the previous regime, Russian troops continue to take Georgians into custody, and those Georgians occasionally turn up dead along the South Ossetian ABL. A Georgian was murdered, and it was recorded on videotape while he was crossing from Abkhazia while on Georgian territory by security forces stationed in Abkhazia. No serious effort at investigation or prosecution by either Russia, which oversees boundary security, or Abkhazia, operating the forces in which the alleged suspect served, is anticipated, and all of the incidents were met with initially far more muted reactions from Tbilisi than those of civil society and opposition groups.

In winter 2015, Energy Minister, Vice Premier, and former Dinamo Tbilisi and AC Milan soccer star Kakha Kaladze, began secretly negotiating with the Russian conglomerate Gazprom to increase the amount of Georgia’s gas purchase from its current 12% of the market, rather than increasing the supply of gas from Azerbaijan. This negotiation was done without any consistent explanation. When pressed for answers, Kaladze offered multiple explanations. According to the soccer star minister, purchasing gas from Gazprom would allow greater diversification of Georgia’s energy supply. He also claimed that Azerbaijan was failing to meet Georgia’s energy needs; that it would be better to trade the gas that Georgia receives from its transit between Russia and Armenia; and that a one-time cash payment would be preferable. All of these arguments were met with various responses ranging from outrage to derision from the Georgian public, who took to the streets as the Georgia-Gazprom talks took place.

Confusion with arriving at a believable narrative for Kaladze’s actions is understandable given his history. Kaladze played for AC Milan but was on the Georgian national team during its pitch against Italy in September 2009 when he scored two goals against his own Georgian team while serving as its captain. Given the odds of such an occurrence happening in the same game, his more lucrative contract with AC Milan, and his expressed opinion that his friend, former Italian Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi, was really the one who persuaded Putin to end the August War of 2008 (despite denials at the time by Berlusconi of doing so, and who has since then defended the invasion) are all factors which may give one pause in taking Kaladze at his word or his analysis of matters affecting Georgia. When combined with the alleged continued financial interest of Ivanishvili in Gazprom, all the more so. Kaladze has since given up the Ministry and Vice-Premiership to run as the number two on the GD party list, behind Kvirikashvili.

Two Sides, One Coin

Increasingly, Ivanishvili and GD pronouncements about political pluralism seem to reflect their preference for pro-Russian or anti-Western nationalist messaging as alternatives to their own rather than pro-Western, but anti-GD. Saakashvili’s government pursued a similar line of argument against those who were deemed insufficiently pro-Western to compromise with significantly on issues of political participation, such as the Christian Democratic Movement, while the Republicans, Free Democrats (FD), and New Rights also had activists who experienced harassment, particularly in the regions outside of Tbilisi. GD has continually characterized any dissent to their policies from pro-Western sources as pro-UNM by default, who they fervently believe represent an even greater threat to Georgian democracy than pro-Russian forces. Saakashvili’s approach, predicated on UNMs self-image as a revolutionary movement that is loudly and unwaveringly opposed to Russia (although they did sell most of the nation’s electrical utility infrastructure to Russia) with a punitive mindset against any, which meant all, other parties with any popular support as insufficiently pro-Western. They made no distinction effectively between openly pro-Russian politicians such as former Parliament Chairwoman Nino Burjanadze and former Prime Minister Zurab Nogaideli and those who were UNM critics but pro-Western, such as Davit Usupashvili and Irakli Alasania, as well as both Davit Gamkrelidze and Giorgi Targamadze, who were accused by Ivanishvili and others of being false opposition fronts for UNM.

Ivanishvili believes that it will be 2030 before Georgia could be sufficiently European, and after 18 years of single party rule, it wouldn’t be unexpected for GD to lose the governing majority in an election. Since its inception, GD has been willing to join with pro-Russian parties like the Industrialists and then ultra-nationalist National Forum, based upon the rationale that this was necessary to defeat UNM. A critical mass of current GD MPs, such as Budget Committee Chair Tamaz Mechiauri, has been persistently anti-Western in their public statements. Therefore, it is hard to imagine a scenario where having forced out the pro-Western Republicans and Free Democrats (FD) from the GD coalition while retaining the formerly anti-NATO Conservatives, GD would actually refuse to coalesce with Irma Inashvili’s vehemently anti-UNM, anti-Western Alliance of Patriots if it was necessary to achieve a governing majority against UNM. In the lead up to their advocacy for membership at the recent NATO Warsaw Summit and the initial delay over EU visa liberalization, the GD narrative toward Europe has been that these actions were necessary in order to avert the ascension of pro-Russian forces despite polling results showing a consistent popular majority for the nation’s Western foreign policy orientation. The GDs continued indulgence of anti-Western political sentiments within its own party while aiding and abetting a more explicitly anti-Western political opposition may supplement the short term goals of dominance over UNM and other pro-Western parties. It also may provide useful leverage in negotiations with Europe, but GD could ultimately end up subverting their current progress by having set the table for a potentially anti-Western majority in the not too distant future.

Open Letters and Contradictions

In his May 2016 letter, Ivanishvili wrote, “some local representatives of international organizations grew so carried away by this machinery of deception that even their headquarters had a hard time keeping them under control. Things got so out of hand that the leaders of the [United] National Movement, not foreigners, would write reports on the situation in the country. Unfortunately, relapses of this type persist. NDI and International Republican Institute have implemented many important projects for our country, for which all we can do is say thank you. It is also true, however, that in their public opinion surveys these organizations, rather suspiciously, employ local specialists closely associated with the [United] National Movement.”

Public opinion surveys have been a particular burr under Ivanishvili’s GD saddle since 2012 when the GD wrote a letter to then-US Ambassador John Bass requesting that the International Republican Institute (IRI) and NDI stop conducting polling until after the election. Despite the polling from both organizations reflecting the trends leading up to the 2010, 2013, and 2014 elections, Ivanishvili and GD fixated on the NDI poll conducted two months before the 2012 election, a month and a half before the prison scandal, to again claim this polling was operated by the UNM, as they have done with every poll to date.

Ivanishvili and GD seem unable or unwilling to acknowledge: 1) if the intent of international NGO polling was to either mobilize UNM supporters or delude the public into supporting them, then why did the 2013, 2014 or 2016 polling never show UNM ahead; 2) that even the most methodologically sound polling reflects only a snapshot in time, predictions can be made based on their trends, but unforeseen events can always impact electoral outcomes; 3) Ivanishvili’s own wildly inaccurate public predictions of his own or UNM margins, based upon undisclosed poll findings in the 2012, 2013, or 2014 elections, something he remarked upon, without irony, following the outcome of the 2013 presidential election; 4) that the UNM polling firm through the 2012 elections, ACT, conducted exit polls for Imedi TV in the 2014 municipal elections, and the results of which GD leaders embraced before the votes were tallied; 5) that in their public claims about their own polling to discredit international polls, this year and previously, were asserted while refusing to provide even basic information about who conducted the polling or what was its methodology. Ivanishvili said privately to international observers in 2012 that he viewed polling as a psychological tool for manipulating the public, which tells us more about his perspective on the utility of gauging public opinion than anything else.

Ivanishvili also seems to have taken internationally-funded civil society organizations, such as the International Society for Fair Elections and Democracy (ISFED) and Transparency International (TI), to task for not rubber stamping GD decisions even going so far as to repeatedly accuse them of being UNM sympathizers, while at the same time, he recruited people directly out of international NGO’s. This seems to confirm a perspective that he either views all NGOs as partisan political fronts, or he has sought to subvert their non-partisan status by cultivating specific individuals within them.

There have also been issues with media freedom and independence under GD’s rule. The inability of the Constitutional Court to render a verdict due to excuses as mundane as non-hospitalized illness and vacations in the Rustavi-2 ownership case prior to the turnover from a majority of UNM appointed judges to GD appointed judges. Repeated and contrary claims of pressure among the now former Chief Justice and other members of the court may further cloud the confidence in whatever verdict is reached. In the Rustavi-2 case, the plaintiff is the brother of a GD MP; the current owner is a former UNM minister; and now a former UNM Defense Minister and independent candidate for majoritarian MP in Gori, Irakli Okruashvili, claims to have new, but so far unsubstantiated, evidence that proves he is the rightful owner. Regardless, the Georgian claim to media freedom will suffer if Rustavi-2 becomes just another GD mouthpiece, albeit through ostensibly commercial, but opaque financial interests just like Imedi TV station was under Saakashvili.

In his May 2016 open letter, Ivanishvili says, “we must fathom that every attempt to push us toward political or religious radicalism, and aggression against a different opinion or way of life, threatens with destruction the fundamentals of our very existence. Therefore, we must exercise special caution and steadfastness when dealing with these issues.”

While some UNM leaders viewed themselves as libertarians who championed advocacy work to achieve greater religious freedom in the predominantly Orthodox Christian nation, they developed a mixed reputation for reforming and deploying law enforcement to crack down on thieves in law, public service corruption, drug abuse (particularly among middle-aged men), as well as drunk driving, seat belt use, and the custom of bride-napping. On the other hand, they funded greater educational opportunities, specifically for ethnic minorities, and provided other religions with the same legal status as the Georgian Christian Orthodox Church. UNM also initiated a dramatic increase in state funding to the Orthodox Church, which has not always supported cultural liberalization efforts intended to enhance Georgia’s EU membership efforts.

On May 17, 2013, International Day against Homophobia, thousands of religious zealots attempted to physically assault fewer than 50 gay rights supporters. Despite a large police presence, which melted away after making a minimal effort to prevent a confrontation between the two groups, the zealots, including some robed priests, sought out the gay rights advocates; smashed the doors and windows of stores which they believed were harboring the gay rights supporters; and then engaged in beating policemen as they tried to prevent the crowd of zealots from destroying a bus which evacuated the remaining gay rights supporters. Despite the assault on police officers, destruction of property, copious amounts of television coverage, and a pronouncement by the Orthodox Bishop, Iacob, lauding leaders of the attack in his church before television cameras, there were practically no consequences for the zealots. Four individuals received only minor fines of 100 lari (less than US$50) and were then acquitted when the use of television footage was denied as evidence in court. The backlash continued in 2014 when Western donors encouraged gay rights activists not to openly observe International Day against Homophobia, and Orthodox Patriarch Ilia II subsequently declared it as Family Day.

Since then, among the positive achievements for GD was the passage of anti-discrimination legislation in 2014, the first of its kind in Georgia, as a significant step towards achieving EU visa liberalization. However, banning gay marriage has become a campaign issue as a result of the benefit seen in its pursuit by those seeking the votes of cultural conservatives. Prime Minister Kvirikashvili has said that he will make it a priority to pass a gay marriage ban after President Giorgi Marghvelashvili denied allowing United Georgia, a new party established in May 2016 by GD MP Tamaz Mechiauri and former GD deputy minister of the diaspora Sandro Bregadze, to place such a constitutional amendment on the ballot. Mechiauri has since withdrawn from running for re-election and has endorsed Ivanishvili and his team. Earlier this year, at the time when negotiations for the GD party list were taking place, Mechiauri was asked what role Ivanishvili played in those negotiations. Mr. Mechiauri responded, “He who pays the piper, calls the tune.”

Banning gay marriage and arguing that allowing gay marriage is the price of EU membership have been among the favorite themes of both the Kremlin and Levan Vasadze, a US-educated millionaire who moved back to Georgia from the UK following the 2012 election. He recently sponsored a gathering of the World Congress of Families, a forum for international right wing groups that are vehemently opposed to reproductive, immigrant, and gay rights. In his keynote address, which preceded similarly themed speeches and workshops, Vasadze railed against the evils of homosexuality and its imposition on Georgian culture from the West and Georgia’s Orthodox brotherhood with Russia. Among the attendees were GD MPs Omar Nishnianidze, Davit Lortkipanidze, and Zakaria Kutsnashvili, the former GD parliamentary faction leader. Kutsnashvili, Vice-Chair of Parliament Manana Kobakhidze, and parliamentary Health Committee chairman Dimitri Khundadze are all on the GD party list or majoritarian candidates for re-election. They are also co-founders of Vasadze’s Demographic Renaissance Foundation, which they established to “save” Georgia from the “demographic disaster predicted by foreign experts.” Ivanishvili publicly supported the organization’s launch in March 2013.

Fire Without a Torch to Pass

Saakashvili has traveled the long way around having exiled himself to avoid prosecution by the GD government for various alleged crimes. He continues to cast himself as the only one strong enough to stand up to Putin’s agenda both in Georgia and now in Ukraine as the Governor of the Odessa Oblast. Having either failed or giving up for the moment on a potential bid for Prime Minister of Ukraine, Saakashvili is now attempting to repeat his performance in the 2013 presidential election in Georgia. Saakashvili’s peripatetic travel and media schedules this year continue to overshadow the far more popular UNM parliamentary leader Davit Bakradze, just as he did in 2013. Having lost his citizenship in a process undertaken by President Marghvelashvili—which may have been more procedurally deliberate but perhaps no less politically-motivated than when Saakashvili’s administration stripped Ivanishvili of Georgian citizenship in 2011—Saakashvili makes online addresses to the UNM faithful at campaign rallies which would seem to violate campaign prohibitions against direct foreign involvement in Georgian elections. He hasn’t expressed a narrative that both consistently atones for the past excesses of UNM and provides a reform-oriented vision of the future. The candidacy of his wife, Sandra Roelofs for the majoritarian seat in the Samegrelo region center of Zugdidi (once held by the Akhalaia family patriarch, who along with his sons, is vilified for their roles in UNM law enforcement controversies) only further serves to underline his imprimatur on the party brand while accentuating the worst aspects of his legacy. Saakashvili has essentially cast the election as a referendum about his return to Georgia by stating it will happen when and if UNM returns to power. Neither Giga Bokeria or the “new faces” of UNM, many of whom were formerly in other governmental roles during the Saakashvili era, have received much public traction beyond the critiques of GD that Saakashvili chooses to articulate.

The outcome of this election could turn on how voters assess the handling of the Georgian economy based on their high expectations from 2012 when the nation’s richest man promised them better days for 2016 based on his own timeline. The Georgian Dream message in the closing days of this election season is one they are hoping Saakashvili may help amplify for them. Audio recordings of his advice to Rustavi-2 owner Nika Gvaramia and UNM leader Giga Bokeria on resisting the station’s possible takeover in November 2015, and in the past few weeks, another set of alleged recordings released on YouTube portray Saakashvili as committed to taking power by any means necessary regardless of the election’s outcome or the potential necessity for coalition building. These audiotapes, combined with his earlier claim that the October election exit poll of Rustavi-2 would be more accurate than the Central Election Commission’s tabulations, put Saakashvili ’s hubris on full display. The GD government has announced a full investigation after tapes of his alleged plans to stage an uprising were leaked. There have been no publicly announced investigative results from the 2015 incident because thus far, there is no indication that either Gvaramia or Bokeria took Saakashvili ’s advice. In this latest incident, the GD government has failed thus far to present any evidence of actual measures being taken by UNM to carry out a coup. Nevertheless, Misha’s on the record rants to the media and his supporters are what understandably provide the most credence to GD’s allegations.

Short of winning an outright majority, it is unclear who UNM would be able to partner with given their history with other party leaders and the declarations of Republicans and Free Democrats of their unwillingness to consider a coalition. There is also a challenge in winning enough majoritarian seats even if UNM were to achieve a plurality among all votes. Control of Parliament could be in doubt until the runoff elections for majoritarian seats at the end of the month, and the 50% vote requirement for those would make the UNM goal of achieving a majority that much more challenging. The necessity of forming a coalition outside of an electoral bloc to achieve a governing majority is unprecedented in Georgian politics, but it is at least one possibility based on publicly available polling data from several months ago. What would happen if UNM gained a plurality of votes nationwide but couldn’t organize a governing coalition?

The Other Players

Davit Usupashvili, the former leader of the Republican Party, was one of two Georgian Dream coalition partners, the other being FD leader Irakli Alasania, who reassured the West in 2012 against claims by the UNM that Ivanishvili was simply an agent of Russian President Vladimir Putin. A co-founder of GYLA and an active opposition leader to Saakashvili’s presidency after initially supporting the Rose Revolution, Usupashvili’s appointment to Chairman of the Parliament demonstrated the potential for mature leadership as a balance to the oligarch’s “L’etat c’est moi” sensibility in his public statements, a personality trait Ivanishvili shares with his nemesis, Saakashvili. However, Usupashvili’s 2013 comment that the Republicans would be the last party to leave the Georgian Dream proved unrealized since the only remaining Georgian Dream electoral bloc ally is Zviad Dzidziguri’s Conservatives. Dzidziguri once sought an audience with Russian MP Vladimir Zhirinovsky in 2010 as a means of improving Georgia-Russia relations, but now supports Georgian membership in EU and NATO.

Tina Khidasheli, a formidable political force within the Republican party in her own right, served as a high profile Minister of Defense for just over a year through the 2016 NATO Warsaw Summit. During that time, she surprised observers in Georgia and abroad with her characteristic boldness in word and deed. She attempted to unilaterally abolish the military draft, which was vehemently opposed by most of the coalition in early 2016. Shortly after her appointment in 2015, she went on an international tour in the lead up to the summit and delivered an ultimatum of sorts to Western audiences by explicitly laying the responsibility upon the West for whether or not it, and presumably the GD government as well, lost ground among Georgians in the 2016 elections if NATO failed to confer membership. This statement implicitly absolved Saakashvili of responsibility for the August War by explicitly stating the refusal of NATO membership at that year’s Bucharest Summit was the only reason for the Russian invasion and continued occupation of the Georgian territories of Abkhazia and South Ossetia. The omission of Saakashvili ’s responsibility did not echo GD talking points at home, and shortly thereafter, the by-election to fill her vacant MP seat in November 2015 became an area of sharp disagreement between Republicans and Irma Inashvili, who narrowly lost amid accusations of voter fraud which were taken up by anti-Western GD MPs such as Tamaz Mechiauri.

At the Republican Party conference in December 2015, Ivliane Khaindrava, deputy secretary of President Marghvelashvili’s National Security Council, used his address to question the relationship between the party and the coalition based upon the by-election outcome and further questioned why there was, both in the GD government and coalition, separate formal and informal leaders—referring to then-PM Garibashvili and ex-PM Ivanishvili. By the beginning of 2016, it was clear that Republicans would stand for election independently of the coalition. Over the past month, both Usupashvili and MP Tamar Kordzaia have referred to their frustration with Ivanishvili’s informal role in the nation’s governance. Expressing his concern about the potential of the anti-Western Inashvili or former Parliament Chairwoman Nino Burjanadze’s Democratic Movement United Georgia entering Parliament, he advocated a constitutional amendment to codify Georgia’s Western foreign policy aspiration. This desire echoed a similarly failed proposal by UNM in 2013; and this past summer Usupashvili was unable to orchestrate a 3/4 vote of the body due to the lack of a quorum.

The biggest problem for Usupashvili is that, other than UNM’s Giga Bokeria, the Republicans are often seen by Georgians as not sufficiently Georgian by virtue of the perception that they are largely secular as opposed to Orthodox Christian in their beliefs. Despite Usupashvili’s personal popularity and his party’s prominence in the GD government cabinet, earlier public polling found them hovering just under the threshold of a six-member faction.

Since the Parliamentary Chairman’s position would require a new occupant if Republicans neither pass the threshold or join with either UNM or GD, it is possible that Kaladze, a former NGO/GD recruit like Tamar Chugoshvili, or a negotiation with a coalition party leader, such as Inashvili or Burjanadze, may be among those in consideration as Usupashvili’s successor. There is also the question of whether Ivanishvili would choose to anoint a Chairman as he did with Usupashvili or allow a contested vote within a governing majority in order to dispel his grey cardinal image? While Ivanishvili has questioned the respective commitments to Inashvili and Burjanadze to Euro integration, both the current GD list of candidates and their past history of uniting with anti-Western elements to ensure the defeat of UNM is well established enough to be of concern.

The prospects for Irakli Alasania’s Free Democrats are harder to discern. He has always been a popular figure in Georgian politics: the son of a fallen martyr at the Battle of Sokhumi in the 1993 Abkhaz war, a decorated soldier, and Georgia’s telegenic Ambassador to the United Nations during the August War. But he failed to win elections for Mayor of Tbilisi in 2010 and against majoritarian MP Akhalaia in 2012 in large measure due to insufficient organizational and fundraising capacity as well as travel outside of the jurisdictions in which he chose to compete. However, having been denied the chance to be the GD candidate for President in 2013 because he had been so bold as to discuss it within his party leadership rather than ask Ivanishvili and his coalition partners first, this is his first national campaign and may play to his personal attributes better than his previous campaigns. Conventional wisdom is that his party will pass the threshold, and he has publicly ruled out joining UNM.

The most notable new entry and apparent political demise just before the election has come from opera singer and philanthropist Paata Burchuladze’s State of the People (SP) bloc. In November 2015, he announced the formation of the Georgian Development movement with offices in Georgia and the US. Then, an International Republican Institute (IRI) poll in March 2016 showed him in a close third place against UNM and GD before he announced in May 2016 that his party would run in the parliamentary elections. Speculation was rife as to whether he was a Trojan Horse for either Saakashvili or Ivanishvili. His apparent access to undisclosed sources of funding like several other parties including several former UNM MPs who had organized two entities, Girchi (Cone) and New Georgia, and his message of navigating the partisanship of the two major forces by being pro-Western but not unfriendly to Russia seemed to have potential for, at a minimum, crossing the threshold. Ivanishvili had publicly dissuaded Burchuladze from running for President in 2013, but since early on in this election, Ivanishvili has claimed repeatedly that Burchuladze was a stalking horse for UNM. This makes little sense given UNMs greater reliance on public funding and presumably smaller pool of available voters since their 2012 defeat, but there was little hard evidence either way as to whether or not Burchuladze was a stalking horse for others.

When it was announced that Burchuladze and the former UNM MP parties would form an electoral bloc, recriminations abounded. While a few lesser known SP activists quit by citing their refusal to work with former UNM MPs, Burchuladze’s chief spokesperson Giorgi Rukhadze, formerly with Targamadze’s CDM, quit and stated that the former UNM MPs were being funded and directed by Ivanishvili. Then, last week, Burchuladze cast the Cone party out from his electoral list, making the same allegations as Rukhadze. Demonstrating either naiveté or incompetence in his approach to politics, it would seem unlikely for Burchuladze to play a major role in the final election results.

Curtain

Michael Corleone becomes what he swore he would not; has Ivanishvili already become a variant on the “undemocratic” ruler he asserts of Saakashvili? Tony Montana’s megalomania consumes his own cunning and capacity; will Saakashvili’s ambitions in two countries destroy whatever positive legacy he claims for both? Three of the Magnificent Seven live on but only one is able to enjoy the fruits of their victory; who may emerge from any of the parties to inherit that fortune? American films are far from the first or even the most familiar stories for Georgians of larger than life figures who arrive at unanticipated destinies. Since Georgia’s halcyon days of Kings Vakhtang Gorgasali, Davit the Builder, Tamar, and Giorgi the Brilliant, or the more controversial times of King Rusudan, Teimuraz I, and the warlord Giorgi Saakadze, their ultimate fates are as much a function of available choices as any foretold fate. Over the period of time that the United States emerged from the rule of a superpower to gradually asserting itself as a superpower in its own right, Georgia has been engaged in a seemingly never-ending struggle with its northern neighbor: Russia. Perseverance in the course of this journey has been full of twists and turns in order to achieve a considerable measure of success—always involving sacrifice and often the source of great disagreement due to the protagonist’s shortcomings or choices at any particular moment in time. Regardless of which one succeeds in doing so, their contributions will only represent the next stop along Sakartvelo’s great journey.

No matter who wins this election, there are still any number of challenges they face, not the least of which is whether or not there will be further progress in establishing a more independent judiciary as well as a criminal justice system that doesn’t distinguish among political party loyalties. If a party should win a plurality of the votes, but fails to win a majority of parliamentary seats, what steps would political leaders take to ensure more not less confidence in governance that reflects popular will? If governing requires another coalition, can that be fully achieved if either Bidzina Ivanishvili or Misha Saakashvili are perceived as the real powers behind whoever occupies the top roles of government? Can public survey research and civil society be accepted and act outside of allegiance to any one electoral bloc? Will popular support for Georgia’s Western aspirations transcend the momentary political advantage some leaders may garner by coddling right wing Russian aligned nativism?

As political events this year in the United States, United Kingdom, Poland, and Hungary demonstrate, there is no finish line, and there are plenty of opportunities for backsliding regardless of membership in Western alliances. Progress always involves struggle. Georgians will make their choice about who will lead their government on October 8. But the questions of what the government initiates, how well it succeeds, and whether or not that reflects the public’s priorities can only be achieved democratically through continued efforts towards greater government accessibility and transparency with the media and civil society in order for the public to acquire greater participation and thereby ensure accountability.

About the author:

*Luis Navarro served as Senior Resident Director for the National Democratic Institute of International Affairs in Georgia (2009-2014) and as both presidential campaign manager and the last chief of staff for then-United States Senator Joe Biden (2007-2009).

Source:

This article was published by FPRI