One Market, One Currency, One People? The Faulty Logic Of Europe – Analysis

By Published by the Foreign Policy Research Institute

By Jakub Grygiel

Were the EU a term paper, a lenient professor would likely give it a D+. It does not deserve an F, as it has survived several crises and has embodied the noble attempt to pacify the European continent. Despite persistent rumors and a perennial sense of foreboding, the EU has not failed yet. And the doggedness of European leaders—manifested by frequent meetings, multiple revisions of their agreements, willingness to expend their nations’ treasure, an obstinate defense of the euro—is akin to a student’s perseverance in editing a paper during an all-nighter. Surely, this counts for something and deserves a few points lifting the grade a bit.

The challenge is that no matter how much time and money European leaders put into this effort, the outcome does not look promising. The paper, to use that metaphor again, is not amenable to editing; it needs some fundamental rethinking. The reason is that its causality is faulty.

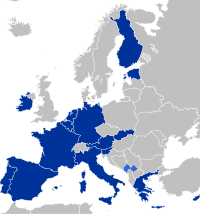

Let me explain. The project of a united Europe is based on the belief that economic unity (itself poorly defined) will lead to political unity. The pooling of the economic aspects of state sovereignty, such as control over production of steel and coal or management of a currency, was meant to constrain and mitigate the nationalistic behavior of individual governments, thereby limiting the possibility of another war. Moreover, in the longer run, the expectation was that a growing economic integration, culminating in the establishment of a common currency, would create a common European identity. A common market, in brief, would create Europeans.

Such a line of causation demanded a technocratic approach. Missing the underlying national unity, the establishment of a common market and a common currency had to be pursued by a supra-national elite with a very tenuous electoral accountability. Absent a demos, the technocrats had to take over the decision-making process. The hope, based on the assumption that a common economy creates a unified people, was that at a certain point a European demos would arise allowing the functioning of a European democracy. But until then, technocracy would have to suffice, and indeed, it was the only way to manage European affairs.

The “democratic deficit” of EU institutions is, therefore, a direct outcome of the faith in the transformative powers of economic structures. The economic, material conditions had to be first set up, then managed by the EU elites sheltered from electoral wishes (notice the EU’s reluctance to allow, and fear of, referenda), and the effect would be the blurring of national differences and ultimately the birth of a European nation. One market, one currency, and—sooner or later—one people.

Moreover, the assumption of a common economy causing a unified people meant also that one could abstract from the actual reality of Europe. There was no need to figure out what Europe, as a cultural entity, really was because the new economic reality would have made a new nation. Hence, the EU technocrats strongly opposed any reference to a common religious background, Christianity, and ignored the three founding cities of Europe: Jerusalem, Athens, and Rome. In their stead, an anemic paean to universal values, reason, and tolerance was much preferred, and the less defined these terms the better. In a way, there were meant to be empty vessels, so anyone could fill them with any substance they desired because they were simply temporary placeholders for the unity that would have sprung from the material conditions created by a common market. One Europe under one currency.

The problem is that the euro fans—on both sides of the Atlantic, one has to add—are wrong. To put it bluntly, they completely messed up the line of causation of political development. The idea that a political unity could arise among geographically contiguous people handling the same coins is akin to believing that two proximate strangers can be joyfully married merely by sharing a checking account. The likely outcome of the latter situation is a depleted checking account and serious marital tensions leading to a divorce. The outcome of the former so far has been a financial crisis, growing national tensions, and a stubborn refusal to face the facts.

The euro was superimposed on economies that are vastly divergent and on polities that have far from uniform fiscal policies. And indeed, in a nod to these differences, the common currency was not accompanied by a fiscal union of the euro countries. That would have to follow the gradual unification of political preferences that should have stemmed in some unspecified future from sharing the euro. Little wonder that countries, such as Greece or Italy, continued their fiscal life as in the pre-euro days, while others, notably Germany, subsidized them through low interest rates. The story is well known at this point and does not need another recounting. What is at the heart of this situation, however, is the naïveté of the fathers of the euro. The blame should not be placed on Italy, Greece, or Spain; they continued to live as they always did, perhaps only more so. The blame is on those who thought that the euro would somehow alter decades-old patterns of political behavior, making, to be brief, all Europeans into Germans.

No fiscal, and certainly no political, uniformity arose among euro-wielding countries. On the contrary, in recent months, there has been a marked resurgence of national tensions, driven in large measure by the sense of German power dictating the terms of the internal bargains of, so far, Greece and Italy. The fact that two democratically elected governments, in Athens and in Rome, had been brought down in the process has only fueled the perception that it was Berlin, and the euro supporters, to call the shots. The presence of French president Sarkozy next to German Chancellor Merkel at the various meetings dealing with ever more pressing crises has not been perceived as a sign of European cooperation—of the continuation of that Franco-German reconciliation that had marked a break with the pre-1945 history—but rather a symptom of deep French fears of being left behind and ending in the “Mediterranean” category of states. It is not a cooperation of equals, but placation of the more powerful German economy.

What should we expect, then? The EU, and the euro zone in particular, will survive, but it is turning into a very different entity from that envisioned at the end of World War II. The Europe of Adenauer and De Gasperi is not the Europe of Merkel, Barroso and Van Rompuy. The latter is characterized by the absence of great statesmen and a related ideological attachment to the euro. The apocalyptic pronouncements of various European politicians claiming that the breakup of the euro will lead to wars attempt to replace reasoning with fear, a classic tactic of an ideology. The argument that a Europe sans euro will lead to the “guns of August” ignores the quite peaceful relations among Western European countries in the 1950s thru the 1990s. Moreover, it assumes that the euro will continue to smooth national tensions, a feat that is quite clearly not being achieved these months. There is growing resentment at the costs of keeping the euro afloat both in fiscally profligate countries and among the taxpaying German electorate (and the resentment is also toward each other). But facts carry no value for an ideology, and the euro defenders prefer to see Europe splinter because of what they think is the right therapy rather than see it prosper under the wrong one.

The outcome so far is that the post-2011 Europe is increasingly a German-led and –managed Europe. Berlin’s role is seen either as regrettable or as desirable, depending in large measure on one’s prejudices toward the EU as a political entity. Those who view the current institutions of the EU as viable in the long-term prefer a more active Germany, tying other European countries to strict fiscal rules and setting the agenda for Europe. Germany as the only savior of Europe is undoubtedly an image of enormous historical ambition. Those who see it as regrettable are reluctant to see another crack in the sovereignty of European states and to have the EU become more German and less European. Both sides agree, however implicitly, that power—and in particular German power—is back in vogue. So much for creating a political entity that was supposed to transcend the politics of old, replacing conflicts of interests with harmony. It appears that the harmony may have to be imposed, after all.

From a policy perspective, the EU has essentially two choices. One is to break up the euro as currently set up, allowing countries such as Italy and Greece to manage their own currencies to match their fiscal policies. The other is to double down and force greater political (especially fiscal) centralization among the euro countries. This would involve most likely concentrating Europe’s fiscal decisions in the hands of EU bureaucracies and, because of its economic power, of Germany’s decision makers, without going through the painstaking and highly uncertain process of seeking popular approval in the various members of the euro zone. This may work for a while, but it is also likely to generate social unrest, intra-European frictions, and further economic stagnation. In the end, the first option seems preferable because sooner or later that is where the euro is headed anyway.

More importantly, a change in economic policy, however dramatic, will only mitigate some of the symptoms of the current crisis. In order to address the fundamental problem of today’s Europe it is necessary to abandon the belief that economic unity will cause political harmony. We are back at the point of departure of this note. Europeans will not be created by the euro and a common market, and what we have right now is a set of EU institutions with no Europeans. But to recognize this leads to the question of what Europe is, a question that neither Merkel nor Sarkozy nor Barroso are willing to ponder because they seem to have little memory of the Christian roots of Europe. Jerusalem, Athens, and Rome are seen as contemporary sources of security and fiscal problems, not as symbols of a great civilizational and religious inheritance that truly unites Europe.

Author:

Jakub Grygiel is the George H.W. Bush Senior Associate Professor of International Relations at the School of Advanced International Studies at Johns Hopkins University, in Washington, DC. He is a senior fellow at the Center for European Policy Analysis, and an international affairs columnist for Giornale del Popolo in Switzerland and Il Mondo in Italy. He received his Ph.D. in Politics from Princeton University.