Pakistan: Painting Itself Into A Corner – Analysis

Pakistan is a land of contrasts. The disparity between the haves and the have-nots in all aspects of normal life stands out as a prime example. However, the most starkly visible contrast is the two very different conceptual understandings within the nation of the role of religion in the State. One is the idea of a secular Pakistan with a thriving pluralistic society, where religion is separate from the machinery of State and where minorities—both religious and ethnic—are protected. The other version, on the opposite end of the spectrum is of a theocratic nation run within the laws of Islam that will be the leader of the Islamic ‘umma’, which theoretically should stretch from Central Asia and the Middle-East all the way through South and South East Asia. It is unfortunate that for most of Pakistan’s independent history, the second concept has prevailed.

The Shrinking Liberal Minority

Established democracies have liberal parties that support important liberal ideas such as human rights, civil liberties, transparency in governance, assured social justice, rule of law etc. In Pakistan there are no political parties that support the concept of liberalism. This is not so surprising in a nation where the idea of democracy has only a tenuous hold on the political firmament. The advocates of liberal rights are, by all accounts, shrinking in size. There is a pervasive sense of fear in liberal circles across the country and they feel under siege. This sense of insecurity has been exacerbated by the media being targeted with hate-mail and the gradual but visible loss of space for the liberal media to function. Reporters without Borders rank Pakistan very low in the index for freedom of the press. It is rated even below Zimbabwe and Venezuela, two countries that are not particularly known for their enlightened civil liberties agenda.

The limited liberalism that existed in Pakistan is now in full retreat. After all, the perspective of true liberalism is on shaky ground in any religious State. There is general consensus that religious and societal intolerance is on the rise in Pakistan and that there are only limited opportunities to express dissenting views without fear of reprisal. Further, the Pakistani liberals function within strong cultural boundaries, even though they view basic international liberalism with a certain amount of acceptance. There is a lack of commitment to gender equality and ensuring the rights of fringe minorities. Even the so-called liberals accept that individual freedoms can only be exercised within the rigid borders drawn by cultural norms. Since the ‘cultural norms’ have over a period of time become heavily influenced by religion, the idea of individual freedom itself is a non-starter.

There are two fundamental reasons for the shrinking liberal space—education and violent extremism. An opinion published in a leading Pakistani newspaper stated that the liberal viewpoint is being subsumed by the ‘low quality, bias-ridden and sectarian education curriculum of schools across the country’. The education system pointedly creates anti-liberal sentiments that nurture violent intolerance in future generations. Since this system has been entrenched for nearly four decades, the intolerance is already visible in the youth of the country. The other factor is the anti-liberal agenda that is supported and propagated by extremist religious groups with a narrow view of Islam. The pressure on liberalism is exacerbated by the political and media support for these fundamentalist and violent groups. Such support may be out of fear of violent repercussions to themselves, but still remain a fact. In a cyclical manner, the ability of the government to enforce the rule of law and the moral fibre of political leadership come directly into question.

In an effort to distance themselves from liberalism, the media portrays liberal groups as pro-Western and supporters of authoritarian governments, including military dictatorships. Over time, the liberal groups have become perceived as anti-common man. In Pakistan, the actual battle to establish a liberal society has already been lost.

The Military Establishment – Strategically Cornered

The Pakistani military, led by the Army, have been the political puppet masters in the country for the past half century. This simple fact cannot be refuted. For decades the Pakistani military has been propped up by the US and China and patronised by Saudi Arabia. Bolstered by this support, the military has always determined the foreign policy formulations of the nation. However, rather swift geo-strategic changes in the past few months have resulted in the US and Saudi Arabia becoming indifferent to the Pakistan Army. This has left the military establishment clinging on to a one-sided relationship with China, the only strand of foreign policy direction that is still holding true.

The Pakistan Army has made a series of foreign policy miscalculations in the past few months. The result has been that the nation has been strategically isolated in the geo-political arena. In order to salvage its reputation, the Army has been quick to pin the responsibility for the foreign policy fiascos on the so-called democratic government. The real culprits are the Army brass who made the decisions. There have been three catalysts for the Pakistan Army having miscalculated and becoming strategically cornered.

First is the Chah Bahar Tripartite Agreement signed on 23 May 2016 by India, Iran and Afghanistan. The agreement caters for the development of the strategically important port of Chah Bahar in Iran and is a three-nation pact to build a transport and trade corridor through Afghanistan. This is expected to strengthen regional connectivity; boost economic growth; and reduce the time to do business with Central Asia and Europe for all three participants. Pakistan, so far the corridor for Afghanistan’s trade and commerce, has been left out of the equation. The Pakistani military establishment was rattled beyond measure by this development and the frustration was visible at the higher levels of its leadership. There was immediate concern regarding the Agreement’s impact on national security and the military resorted to a knee jerk reaction. It decided to close down the Torkhan border with Afghanistan and started to enforce restrictive visa requirements for travel. However, the impact has been on the common people and not at the strategic level of policy making.

Second is the continuing improvements in the Indo-US strategic partnership. The maturation of this bilateral relationship also involves deepening of military cooperation between the two nations. Pakistan feels that the increasing closeness of India and the US increases the systematic imbalance that exists between it and India in conventional and nuclear asymmetries. Pakistan perceives a strategic disadvantage. There is also deep resentment about the Indian engagement with Saudi Arabia, Iran and Afghanistan, which Pakistan believes is moving these nations to be more amicable to India. The military dictated foreign policy of Pakistan is heavily reliant on the ‘Muslim’ card that has consistently been played against ‘Hindu’ India. Much to Pakistan’s chagrin, the nations that are becoming more accepting of India are all Muslim nations. The military does not have any ready answers to this changing geo-strategic situation.

Third is India’s conscious development of its strategic capabilities and clear intention to assume a greater role of power in the region. Its attempts to achieve regional strategic superiority in South Asia is visibly evident. India’s ambition is to achieve a security and power balance with China. In Pakistan’s eyes this will be tantamount to a greater geo-political imbalance in India’s favour. The US patronage towards India is being squarely blamed for this state of affairs, further entrenching the anti-US paranoia.

Since all three reasons are considered to be India’s ‘fault’, it is more than likely that Pakistan Army would increase its asymmetric response through increasing suicide bomber attacks in Indian territory as well as through ramping up the on-going proxy-war in Kashmir. There is already a noticeable increase in the anti-India and anti-US criticism and rhetoric coming out of Rawalpindi, the military headquarters in Pakistan. At the same time the military is starting to hide behind a façade of blaming the ‘Foreign Office’ for the foreign policy debacles. Irrespective of the face-saving measures that Pakistan Army is adopting, the fact remains that it has lost geo-political standing and is an internationally discredited organisation. The other irrefutable fact is that it has single-handedly led Pakistan into a foreign policy nightmare.

If the current situation is allowed to continue on the same path and translated to policy initiatives, it will eventually lead to further strategic isolation of the nation. Almost as a corollary, the situation will increase the chances of attacks against India, to shore up the crumbling credibility edifices of the Pakistan Army. At the current moment, the civilian government is effectively out of the loop in formulating national foreign policy, which is being overseen by the Pakistan Army leadership. That the Army still runs the country is demonstrated by the on-going internal security campaigns that were unilaterally initiated by the Army without seeking the consent of the civilian government. The military is convinced that China is the answer to all Pakistan’s woes, both security and foreign policy. They do not seem to have factored in the underlying uncertainty that continues to exist regarding Chinese support in an extreme crisis.

Foreign Policy Debacle

All nations attempt to develop and practice a dynamic foreign policy to meet domestic requirements and to cater for changing global political developments. A viable foreign policy is built on recognising and protecting the long-term interests of the nation and will be oriented towards maintaining peace on its borders. Pakistan, and particularly its military establishment, is enmeshed in a situation where it is unable to identify and/or define national interests other than through a single prism of ‘India-hate’. It also has a biased view of and difficult relations with all its neighbours, with the exception of China. Pakistan does not have any dependable bilateral relationship with any country other than China, an indicator of its broad isolation and foreign policy failure. China is officially called the ‘time-tested friend’ in Pakistan. The ground reality is somewhat at variance with many anti-Chinese groups active in the country. There have been attacks on Chinese engineers and workers in the country, especially in Baluchistan, which is becoming a challenge for the internal security agencies. In an effort to pass on the responsibility, Pakistan blames India for these attacks.

Pakistan started to become regionally isolated when the international community commenced its military effort to neutralise the Taliban in Afghanistan. This turned to international isolation when the Western nations embroiled in the fray started to realise the double-game that Pakistan was playing in the conflict. The three regional nations other than China that should be important to Pakistan’s foreign policy are India, Iran and Afghanistan. There has been no tangible improvement in its relationship with India, which remains in the proverbial ‘one-step forward, two-steps back’ march. The bilateral relations are coloured by the hawkish attitude of both the nations.

Pakistan had good relations with Iran during the regime of the Shah. However, after the Islamic Revolution that deposed the Shah, Pakistan’s foreign policy towards Iran was dictated by the US and Saudi Arabia. There was no real interaction for a number of years between the two nations. Even after the lifting of the sanctions against Iran a year ago, Pakistan has been reticent in its dealings with Iran and has not been able to re-establish firm relations. The Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif also holds the foreign policy portfolio. His pro-Saudi Arabia stance could be a factor in Pakistan maintaining a distance from the theocratic Shia Iran.

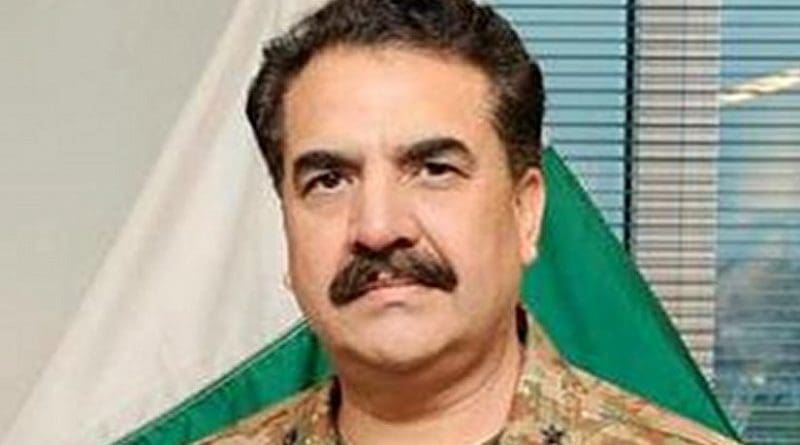

The Pakistan Army has a strangle hold over the nation’s foreign policy. In late-June 2016, the Chief of Army General Raheel Sharif called a Cabinet Meeting of the civilian government at Army Head Quarters in Rawalpindi. This in itself is an extra-ordinary state of affairs in a democratic nation, where the military is at least nominally subservient to the parliament. It is reported that the Army Chief belaboured the ministers for the nation’s foreign policy failures, especially in comparison to the diplomatic successes that India is notching up. The Army retains its predominant position only through its concerted anti-India rhetoric and actions. It uses its own intelligence arm, the ISI, to block any reconciliatory move towards India by the civilian government.

Proof of Failure – Afghanistan

The proof of Pakistan’s foreign policy failure is its relationship with Afghanistan where the struggle for Pakistan’s regional relevance is being played out. Pakistan claims that it has improved relations with a majority of the Pashtun population that straddle its border with Afghanistan. There is a dichotomy between this claim and reality, which shows that the Pakistan Army seems to trust only some regressive and fundamentalist Taliban forces. Further, the shifting of Pakistan Army’s internal security operations to its western border has been labelled by the Army as being important to Pakistan’s foreign policy. However, it has created an impetus for further isolation from its neighbours and aided India’s expansion of its soft power to Afghanistan. India has helped Afghanistan build its new parliament and also the $ 290 million Salma Dam, which is the largest hydro-electric power project in the country. India’s soft power diplomacy is well-entrenched in Afghanistan and effectively counters Pakistan’s military activities.

In comparison to India’s profile, the perception in Afghanistan is that Pakistan is continually muddying the waters while at the same time denying any wrong doings. The reality is that Pakistan has failed to maintain reasonable relations with Afghanistan and Iran, let alone India, leading to geographical and political isolation. While it may make economic sense to foster closer relations with China, it will not provide the answer to the turbulence emerging from Pakistan’s western borders. Pakistan’s dealings with Afghanistan is a pointer to the confused state of its foreign policy. The challenge is not of recent making either. There is a historic precedent to its rivalry with Iran over control and influence of Afghanistan. Pakistan has always wanted to be the sole influence in Afghan politics and cannot envisage another nation having even a minor political sway over Afghanistan.

Before the Iranian revolution and at the height of the Cold War, both Pakistan and Iran were firmly in the US camp and considered dependable allies of each other. However, in 1972 the then Prime Minster Z. A. Bhutto secretly offered military facilities to the US forces in Baluchistan so that they would not be based in Iran. This was a clandestine attempt to undermine the Shah of Iran’s relationship with the US. Double-dealing with friends and allies has a long history in Pakistan’s foreign policy initiatives. There was an uneasy cooperation between Iran and Pakistan in matters regarding Afghanistan in the 1960s, but that was short-lived. The stand-off continues and influence in Afghanistan is now a contentious factor in Pakistan’s relations with all its neighbours. The situation has been exploited by both al Qaeda and the Islamic State who are making inroads into Afghanistan.

Afghanistan is an unequivocal example of Pakistan Army’s inability to understand the changing geo-politics of South Asia. The policy being pursued in Afghanistan is also an indicator of the civilian government’s inability to reign in the military establishment. In June 2011, Pakistani Taliban attacked the Afghan provinces of Kunar, Nangrahar, Khost and Paktia, after heavy artillery shelling and supported by Pakistan Army helicopters. In June 2016, Pakistan Army resorted to heavy shelling in the Torkhan area of the Khyber Pass, about 50 kilometres from Peshawar. This was triggered by Pakistan attempting to build a border gate and enforce strict travel regulations that led to exchange of fire with the Afghan forces. The reaction in Afghanistan was illustrative of the deepening divide between the peoples of the two nations—there were emotional demonstrations with Afghans shouting ‘Death to Pakistan’ in Lashkar Gah near the border.

Pakistan is home to 14 terrorist organisations. It continues to attack Afghanistan with a combination of Taliban, members of the Haqqani group and an ad-hoc ISI brigade created specifically for the purpose. Further, regulars from the Mujahidin battalions disguised as Taliban take part in these attacks. Afghanistan has produced ample proof of Pakistan Army’s collusion in these terrorist attacks. In effect, Afghanistan President Ashraf Ghani has called Pakistan’s bluff. He has openly called on Pakistan to battle the Taliban rather than ‘attempting’ to bring them to the negotiating table. He has also provided sufficient proof of the Taliban leaders being sheltered in Peshawar and Quetta. Further, the Afghan Government has officially announced that it will use all its diplomatic efforts to isolate Pakistan. The opinion in the US is also gradually changing as there is greater realisation of Pakistan’s foreign policy double-dealings. Newspaper editorials like in the New York Times are now unambiguously asking the government to take action against Pakistan.

At the core of the relationship between Pakistan and Afghanistan is the question of the international border that divides the two nations. The Durand Line that is the de facto border divides the Pashtun tribal lands and many tribal societies. This line is not recognised by Afghanistan as a proper border. Successive Afghan governments of all political affiliations have refused to recognise the Durand Line as the international border.

It is an arbitrary line drawn by the colonial British Indian administration to facilitate administrative efficiency. A treaty between the British and successive Afghan kings continued to accept the division till as late as 1921. However, starting with the division of the sub-continent and the granting of independence to India and Pakistan in 1947, the Afghan government repudiated the sanctity of the old treaty and the Durand Line. It is noteworthy that the Taliban government of the 1990s—propped up and recognised by Pakistan—also refused to accept the Durand Line as the border and did not drop the long-standing Afghan claim to Pakistan territory east of the Line.

Currently the Afghan government is critically dependent on Pakistan to ensure the flow of trade and commerce. However, there is recognition that this cycle of dependency has to be broken if the nation is move ahead towards a semblance of peace and stability. The tripartite treaty with India and Iran is an important first step in this direction. Obviously Pakistan is not comfortable with the initiative and the direction it is taking. The Pakistan Army, controlling the nation’s foreign policy with an iron hand, is not able to fathom the underlying needs of the Afghan people. It continues to support the Taliban while vehemently denying such support even in the face of irrefutable evidence. This is an embarrassment. However, the discomfiture does not seem to affect the military leadership who brazenly continue their double-dealings. Pakistan’s Afghanistan policy is a prime example of the failure of its foreign policy. More importantly it is an indication of the military establishment being completely out of touch with the reality of contemporary geo-politics.

Conclusion

In the proverbial ostrich-like fashion, Pakistan continues to pursue its ideology of hate and intolerance. A case in point is the systematic persecution of the Ahmadia sect that started as early as in 1947 on the eve of independence. This was despite the fact that the first foreign minister of independent Pakistan, Muhammad Zafrullah Khan, was himself an Ahmadia. The persecution was given tacit and indirect legal sanction through some ordnances passed by the dictator General Zia-ul-Haq and also by the democratic government of the Pakistan People’s Party, successively led by the Bhutto father and daughter team.

State-backed religious zealotry, unchecked at the national, provincial and local levels, has triggered and nurtured the growth of extremism in Pakistan. The zealotry is so deep rooted that it has even spread to the Pakistani diaspora living in Europe and elsewhere, as indicated by the killing of an Ahmadia shop keeper in the UK and the distribution of leaflets calling for the killing of Ahmadias. The State—whether represented by the Army or the civilian government—has lost control in Pakistan and has abrogated all responsibility for the well-being of the people. The national narrative has been hijacked by rogues and assassins who spread terrorism across the globe in the name of religious jihad. Pakistan’s use of terrorism as an instrument of state policy has now come home to roost. The Army has reached a stage where it is incapable of doing anything about this, having painted itself and the nation into a corner. The collapse of ‘normalcy’ is writ large in the future of Pakistan.

First published in at sanukay.wordpress.com

This is just a bias, personal opinion

Excellent Analysis.