The Long Way Round: Syrians Through The Sahel

By IRIN

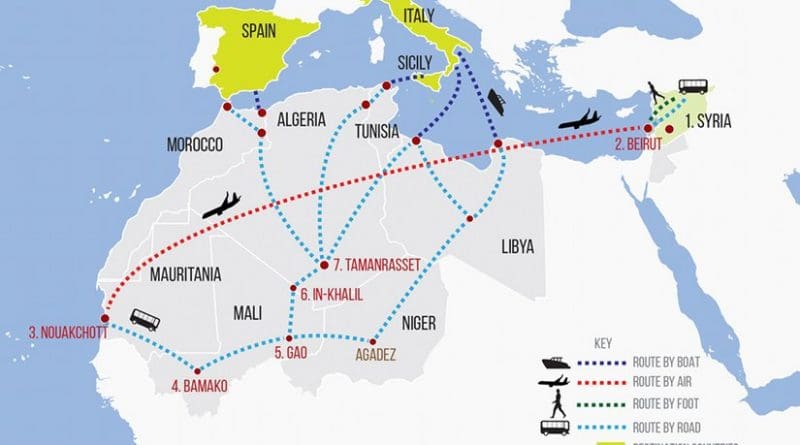

As other options narrow, a small but growing number of Syrians are attempting a new and circuitous route to Europe: flying more than 3,000 miles to Mauritania in West Africa and then travelling overland with smugglers on the ancient salt roads from Mali through the Sahara.

By Katarina Höije*

The low, mudbrick houses slowly come into focus against the desert sky as the old, beat-up pickup truck enters the Tilemsi Valley, near Gao, some 1,200 kilometres northeast of Mali’s capital, Bamako. As the vehicle comes to a halt, a dozen or so men descend to stretch their legs. Women and children remain in the hot car.

Among the men is Mohamed Abdelaziz*. He left his hometown of Homs in western Syria in early 2012, when fighting intensified between government forces and the Free Syrian Army.

After spending time in a refugee camp in Lebanon, he recently joined some trailblazing Syrians on a long and hazardous journey: first to Mauritania in West Africa, then south to Bamako in Mali, before heading northeast to Gao and on northwards along the ancient trade routes that crisscross the Sahara desert.

“There are very few safe routes and those that remain are becoming increasingly difficult to cross,” Abdelaziz told IRIN. “I considered going through Turkey to reach the Greek islands, but eastern European countries are all closing their borders.”

He said staying in Lebanon was not an option as it was difficult to find work or obtain legal status.

The road less travelled

Mauritania is one of the few Arabic-speaking countries where Syrians can travel without visas, and there is a growing community of several hundred living in the coastal capital Nouakchott.

Abdelaziz was reluctant to say how he ended up in Mauritania before coming to Mali, but it is likely that he is part of the growing trend of Syrians flying directly there from Lebanon.

“We have seen an increase this year [of Syrians in Mauritania],” Sébastien Laroze, a Mauritanian-based representative of the UN refugee agency UNHCR told IRIN. “They board a plane in Beirut… and arrive straight in Nouakchott… where [they] travel in groups to Mali… and then continue together to Algeria.”

Syrians used to fly directly to Algiers and cross the western border into Morocco to reach the Spanish enclaves of Ceuta and Melilla, a popular gateway into Europe. But Algeria imposed new visa restrictions on Syrians in March, prompting an increasing number to attempt this riskier and much longer journey.

“Since Algeria enforced visa regulations on Syrian nationals, we have seen more and more Syrian refugees moving from Mauritania through northern Mali and crossing into Algeria assisted by smuggling networks,” UNHCR’s spokesman in Rabat, Anthony Berginc, told IRIN.

“Once in Algeria they might spend up to two years before continuing to Morocco, some with the goal of reaching Europe.”

One recent report suggests a backlog of between 700 and 1,500 Syrians are waiting in the Moroccan border town of Nador for their chance to walk to the Spanish customs post at Melilla. Although many of these Syrians came overland through Egypt, Libya and Algeria, it suggests the route from Mauritania and through the Sahel is becoming more popular.

A smuggler’s paradise

Human traffickers in Mali told IRIN that they help transport as many as a dozen migrants – of mixed nationalities – every few days from Bamako to Gao and then on to In Khalil, a lawless, smugglers haven next to the Algerian border.

From there, it is a journey of several hours in pickup trucks across the desert to Tamanrasset, an ancient salt route long used by traders on camel back. An alternative route, popular with migrants from Western and Sub-Saharan Africa, tracks east through the Sahel to Agadez in Niger and joins up with the established Central and East African migration pathways to Libya, where there is a chance of a boat to Europe.

Routes through the Sahel are notoriously dangerous. Dozens of people die crossing the Sahara desert each month, according to the International Organization for Migration, although it is almost impossible to determine the precise number due to the vast area and the inhospitable environment.

The lawless Kidal region, north of Gao, is also a crossroads and a haven for smugglers: tobacco, cocaine and other goods are trafficked routinely through In Khalil and other border routes. African migrants have long used this area to cross into Algeria, but smugglers said a significant number of those recently being smuggled across the border are Syrian.

Amadou Maiga,* who smuggles cigarettes, petrol and food supplies through the Sahel, said he had started taking on “human goods” as well.

He told IRIN that the number of Syrians who attempt the route each month is increasing. Recently, he helped 35 Syrian refugees make their way across Mali. Another four were sleeping on the floor of his workshop.

“They are all desperate to reach Europe,” Maiga said.

The IOM recently gave assistance to a group of 36 Syrians – including 17 children and nine women – who had come from Mauritania and were heading through Gao to Algeria. It is not clear if this was the same group Maiga was referring to.

“It is becoming more evident that it is not an isolated case,” IOM’s representative in northern Mali, Aminta Dicko, told IRIN in an email. “We think that more and more of them (Syrians) are on this route.”

More Syrians = more money

Along the way, the migrants’ money is transforming life in remote desert towns.

In a country where most people live on less than $2 a day, the Syrians, who can afford to pay for a higher quality of service, are a welcome addition.

Depending on the mode of transport, the cost of the trip normally starts at $300, once all middlemen’s fees are included. Some migrants have paid much more, depending on the route and the risks involved, according to drivers and smugglers in Gao. With 15 to 20 people per car, drivers can earn upwards of $4,000 for a single journey.

“People become millionaires in a few years,” a Bamako businessman with connections in the trans-Saharan smuggling ring, told IRIN.

Policemen, soldiers, and local officials who turn a blind eye to the migrant trade often earn more in bribes than they do from their regular salaries.

Long stretches of the route from Bamako to Gao and on into Algeria are controlled by armed groups, such as Ansar Dine and Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb. Trucks and private cars passing through Gao and Kidal are regularly either stopped and robbed of cargo, or forced to pay hefty “taxes” imposed by rebel groups.

“You can always negotiate with the armed groups, as most of them are just here for the money,” said Oumar Diallo,* a former tourist guide turned smuggler.

Is the genie out of the bottle?

In Gao, where residents say that Syrians often linger for weeks after reaching what is considered the “gateway to the Sahel,” business has picked up in recent months. Once a sleepy town, the streets next to the main market are jammed with Toyota pickups. New villas, built with cement, are starting to outnumber the mud-brick homes.

“It’s like a boomtown with lots of people profiting,” Abdrahamane Togora, who monitors migration patterns for the government in Bamako, told IRIN.

Togora worries, however, that the growing demand for human smugglers could attract criminal groups as well, particularly those involved in the illegal arms or drug trades, or traffickers keen to exploit or deal in human cargo.

“We can’t stop people from moving, but we are certainly following the situation,” he said. “If you tried to stop the business, they, the traffickers, would not accept it.”

Maiga agreed. “The Malian army can’t control the territory and the authorities don’t dare to intervene.”

He explained that although it might be illegal, once you have ‘valid’ papers, there is little the authorities can do to prevent people from getting on a truck. “Soldiers and police can stop the trucks, but as long as the passengers don’t say ‘we paid this person to bring us here,’ it’s very difficult to expose the traffickers and smuggling networks.”

Maiga said he had no plans to stop transporting Syrians through the Sahel. “I can help these people, so that’s what I do.”

No good option

Official figures on how many migrants are now taking the ancient trade routes through the Sahel are not available. The IOM says the Malian government is responsible for tracking migrants and refugees who arrive there. The government told IRIN it is “monitoring the situation.”

The Global Initiative against Transnational Organized Crime says between 5,000 and 20,000 migrants were smuggled last year through Mali towards Libya, including by trans-Saharan nomadic tribes, such as the Tuareg in northern Mali and southern Algeria. The vast majority of these are non-Syrians from Central and Western Africa who are finding Ceuta and Melilla to be an increasingly difficult avenue to access Europe, as they are often left to languish in Morocco indefinitely, in deplorable conditions.

The popularity of the trans-Saharan route for Syrian refugees trying to get to Morocco appears to be a phenomenon that has been building since Algeria changed its visa rules in March/April. As countries in Europe continue to increase border security, particularly along the most popular Western Balkan route, many more could soon follow in Abdelaziz’s footsteps.

“To get here [to Mali] was not easy,” he told IRIN. “To continue to Europe is not easy. But to stay here is not easy either.”

*not real name

*Katarina Höije is a Bamako-based journalist

Edited by Jennifer Lazuta and Andrew Gully