Shame Power: The Philippine Case Against China At Permanent Court Of Arbitration – Analysis

By Published by the Foreign Policy Research Institute

By Felix K. Chang

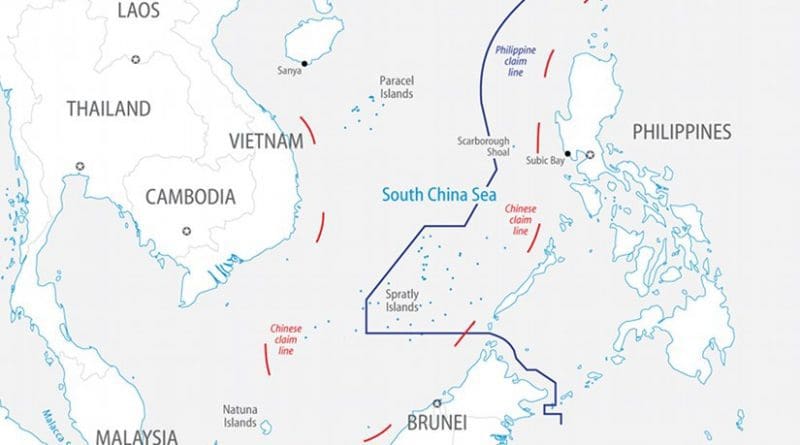

(FPRI) — The Philippines may not have much conventional power it can bring to bear in its territorial dispute with China in the South China Sea. But today it demonstrated that it does have the power to shame China on the international stage. After hearing the Philippines’ legal case against China’s South China Sea claims, an international tribunal at the Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA) ruled that there was “no legal basis for China to claim historic rights to resources within the sea areas falling within [its] ‘nine-dash line’” claim. The ruling went even further. It detailed how China had aggravated the dispute and “violated the Philippines’ sovereign rights in its exclusive economic zone” by constructing artificial islands and interfering with Philippine fishing and energy exploration.[1]

The ruling was a long time in coming. In 2013 Manila brought its dispute with China to the PCA, an option provided for under the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). Normally, the PCA’s tribunal would have heard the arguments of both parties in a dispute before making its ruling. But in this case, it heard only those of the Philippines. China refused to participate in the proceedings, arguing that the tribunal had no authority over its maritime borders. So to ensure that the tribunal had adequate authority to make a ruling, Manila asked it to narrowly assess “the sovereign rights and jurisdiction of the Philippines over its maritime entitlements” in the South China Sea. That allowed the tribunal to make a ruling without Chinese participation. It also obliged the tribunal to consider the validity of China’s overlapping “nine-dash line” claim under UNCLOS.

Of course, the tribunal’s ruling does little to compel China to change its behavior in the region. China has already changed the status quo in the South China Sea. Over the last two years China has reclaimed enough land to turn the features it occupies in the Spratly archipelago into man-made islands large enough to support military-grade airfields and facilities. China is unlikely to abandon them now.

Over the long term, the tribunal’s ruling puts the Philippines in a better position to pursue future legal action. For the time being, however, what the tribunal’s ruling does do is to publicly shame China. Once, that mattered to China. In 1997, when a United Nations commission was considering a resolution critical of China’s human rights record, Beijing mounted a major diplomatic campaign, including tours by Chinese leaders and offers of trade deals, to dissuade other countries from voting for it. The fact that China did so to avoid international criticism suggested that it mattered to China. Today it does not seem to matter as much. China has grown too economically and militarily powerful. That has made it more confident in its ability to shape its geopolitical environment on its own terms.

One of the first countries to feel the brunt of China’s new confidence was the Philippines. Perhaps that was because the Philippines had become an easy target. After the Cold War, it allowed its navy and air force (the two services that matter in the South China Sea) to fall into disrepair. At the same time, it distanced itself from the United States. So, when China began asserting itself in the South China Sea, there was little Manila could do. That much was clear when China blocked access to Philippine-claimed Scarborough Shoal in 2012 and prevented Manila from resupplying by sea its outpost on Second Thomas Shoal in 2014.

Yet Manila refused to back down. It took its case against China to the PCA. It also began to rebuild its armed forces and strengthen its security ties to Japan and the United States. In March, the Philippines and the United States held their first joint naval patrol in the South China Sea and finalized their Expanded Defense Cooperation Agreement, allowing American forces to rotate through Philippine military bases. Meanwhile, the Philippines has hosted a growing number of Japanese naval vessels, including a submarine, at its naval base in Subic Bay.

Nonetheless, the Philippines may change its approach to China. Former President Benigno Aquino, whose perseverance had been so critical in keeping international pressure on China, left office in June. His successor, Rodrigo Duterte, seems ready to take a softer line towards China. During his presidential campaign, he said that he would work to shelve the Philippines’ dispute with China; and that he was open to joint development of the South China Sea, especially if Chinese economic assistance was forthcoming. Such comments should encourage Beijing. But it remains to be seen how China responds.

In the meantime, China is likely to brush off the tribunal’s ruling. But the Philippines’ success at the PCA has not gone unnoticed. Other countries have followed the tribunal’s proceedings with keen interest. Encouraged by the Philippines, Vietnam added its position to the proceedings in late 2014. Indonesia has said that it would consider its own case too, if negotiations with China failed. Even Japanese lawmakers have discussed the possibility of international arbitration over China’s offshore drilling activities in the East China Sea. If the Philippine case sets a precedent that others follow, Manila will have demonstrated that it has not only the power to shame, but also the power to inspire.

About the author:

*Felix K. Chang is a senior fellow at the Foreign Policy Research Institute. He is also the Chief Strategy Officer of DecisionQ, a predictive analytics company in the national security and healthcare industries. He has worked with a number of digital, consumer services, and renewable energy entrepreneurs for years. He was previously a consultant in Booz Allen Hamilton’s Strategy and Organization practice; among his clients were the U.S. Department of Energy, U.S. Department of Homeland Security, U.S. Department of the Treasury, and other agencies.

Source:

This article was published by FPRI.

Notes:

[1] Matikas Santos, “Key points of the arbitral tribunal’s verdict on Philippines vs China case,” Inquirer.net, July 12, 2016.