What If There Were No Profits? – OpEd

There is a false dichotomy here between profits and poverty. What Pope Francis doesn’t see is that without profit companies go out of business, all of the people who work for them lose their jobs, and poverty grows.

By Dylan Pahman*

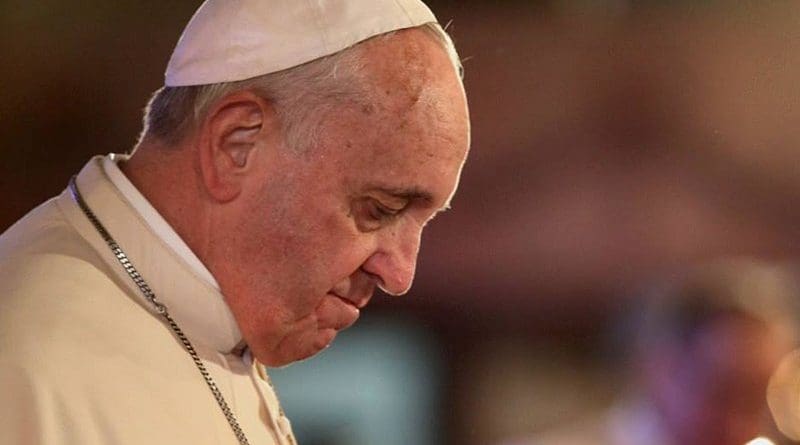

In a 2013 lecture, Pope Francis urged his audience to solidarity with the poor and marginalized. This is one of the most consistent and laudable emphases of his pontificate.

But sometimes what is seen overshadows what is not seen. “If you break a computer it is a tragedy,” said Francis, and he continued:

… but poverty, the needs, the dramas of so many people end up becoming the norm. If on a winter’s night, here nearby in Via Ottaviano, for example, a person dies, that is not news. If in so many parts of the world there are children who have nothing to eat, that’s not news, it seems normal. It cannot be this way! Yet these things become the norm: that some homeless people die of cold on the streets is not news. In contrast, a ten point drop on the stock markets of some cities, is a tragedy.

To Francis, this is because “men and women are sacrificed to the idols of profit and consumption.” I would like to emphasize that what the pope sees is right. Profits should not be more important than people. Waste is bad stewardship. The plight of the poor deserves more regular media attention. Solidarity is a virtue. All of these things are true, but Francis — like many others — fails to see the good of profit.

There is a false dichotomy here between profits and poverty. Stock markets measure company value, which is related to profit but not the same, and people can idolize that. But what Francis doesn’t see is that without profit companies go out of business, all of the people who work for them lose their jobs, and poverty grows. As Adam Smith put it, “it is only for the sake of profit that any man employs a capital in the support of industry” in the first place. Without profit there is no industry, and without industry there are no jobs. Profits do not require our ignoring the poor. And the poor will continue to be poor without profits. Rightly understood, concern for the stock market may in fact be concern for the poor on a massive scale.

The answer to the question, “What if there were no profits?” requires us to think through all the things profits are used for. Profit is the leftover when revenues exceed expenses. If there is no profit, it means companies can’t pay their bills. Through loans, startups will often be able to endure years without profits. This is often necessary. But if they never end up making profits, pretty soon the loans will come due and the money needed to pay them won’t be there. Companies will need to sell capital to pay them, and if that is not enough they will need to file for bankruptcy to renegotiate their debts. In either case, the company is done, and everyone who works for it will soon be unemployed.

So the first thing profits are used for is simply to keep businesses alive. There are many more uses than that, however. A company could conceivably stay alive by breaking even, where revenues equal expenses. But with profits, the company can expand, hire more people, pay higher wages, and diversify its product line. Furthermore, profits are often also used to invest in other companies, for example through 401(k) programs. Typically both employers and employees contribute to them. Unless the employee chooses to invest only in government bonds (which can also be good for society), they will be using some of their income and some of the company’s profit (now an expense) to contribute to other enterprises in an economy, making more products, more profits, and more jobs possible.

As we’ve already seen, without profits, business would be impossible. And without business, there are no jobs. The alternative to profits is universal poverty. That is exactly what we can see in dystopian dictatorships like North Korea: the otherwise unseen effects of taking away both profits and private property. Same planet, same dimension.

In Centesimus Annus, Pope John Paul II approached the issue with a bit more nuance:

The Church acknowledges the legitimate role of profit as an indication that a business is functioning well. When a firm makes a profit, this means that productive factors have been properly employed and corresponding human needs have been duly satisfied. But profitability is not the only indicator of a firm’s condition. It is possible for the financial accounts to be in order, and yet for the people—who make up the firm’s most valuable asset—to be humiliated and their dignity offended. Besides being morally inadmissible, this will eventually have negative repercussions on the firm’s economic efficiency. In fact, the purpose of a business firm is not simply to make a profit, but is to be found in its very existence as a community of persons who in various ways are endeavouring to satisfy their basic needs, and who form a particular group at the service of the whole of society. Profit is a regulator of the life of a business, but it is not the only one; other human and moral factors must also be considered which, in the long term, are at least equally important for the life of a business.

Here John Paul II sees all of the same concerns as Francis: solidarity with workers, people over profits, and so on. Yet he also sees the often-overlooked importance of profit. It is “an indication that a business is functioning well,” and it “means that productive factors have been properly employed and corresponding human needs have been duly satisfied.” Rightly sought and understood, profits are a good thing.

Theologically speaking, such wholesome profit is what happens when people fulfill the command to “be fruitful” (Gen. 1:28). Or as Adam Smith dryly put it, “The produce of industry is what it adds to the subject or materials upon which it is employed. In proportion as the value of this produce is great or small, so will likewise be the profits of the employer.” When people profit from the creation of new wealth, it is because they take the world God has given us and make something more of it for the good of others and for God’s glory. It would be shameful to throw that away.

This commentary was excerpted and adapted from Dylan Pahman’s Foundations of a Free & Virtuous Society (Acton Institute, 2017). The book is currently for sale on the Acton Bookshop.

About the author:

*Dylan Pahman is a research fellow at the Acton Institute, where he serves as managing editor of the Journal of Markets & Morality. He has a Master’s of Theological Studies in historical theology with a concentration in early Church studies from Calvin Theological Seminary. He is also a layman of the Greek Orthodox Church.

Source:

This article was published by the Acton Institute