What A US-Pakistan Nuclear Deal Could Mean For India – Analysis

By Observer Research Foundation

By C. Raja Mohan*

India has seen this movie before and it does not have a happy ending. As the idea of a nuclear deal between the United States and Pakistan gains some traction in Washington, Delhi is unlikely to lose much sleep.

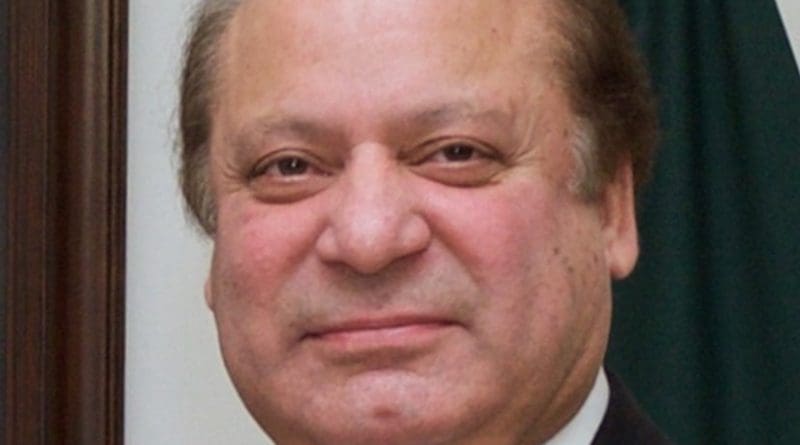

One of Washington’s well-briefed columnists, David Ignatius, has revealed this week the outlines of a nuclear agreement that the US is said to be negotiating with Pakistan. These talks could be at the top of US President Barack Obama’s agenda with Pakistan when he receives Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif at the White House later this month.

Although the deal has been termed a potential “diplomatic blockbuster”, its inherent contradictions may make it difficult to sell in both the US and Pakistan.

The hope for a nuclear deal between America and Pakistan was born the very moment US President George W Bush and Prime Minister Manmohan Singh unveiled the historic civil nuclear initiative in July 2005.

In typical fashion, Pakistan simultaneously opposed the US deal with India and demanded one for itself on the same terms that Washington had offered Delhi.

The Bush Administration refused to entertain any proposal for a nuclear accommodation with Pakistan. It insisted that the deal with Delhi was an exception that couldn’t be replicated with Islamabad.

The Obama Administration, in contrast, has been ambivalent and allowed itself to come under sustained pressure from Pakistan’s supporters in Washington.

In a Washington Post column on Wednesday, Ignatius says the US is ready to lift international restrictions against civilian nuclear commerce with Pakistan in return for significant voluntary restraints on its nuclear weapons programme.

These limits, according to The Post, would be defined by the principle that Pakistan should “restrict its nuclear program to weapons and delivery systems that are appropriate to its actual defence needs against India’s nuclear threat”.

The idea of a nuclear deal with Pakistan has had considerable support from sections of the American non-proliferation community. A recent report published by the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace and the Stimson Centre in Washington has enumerated in greater detail the possible American demands on Pakistan.

In the report titled A Normal Nuclear Pakistan, Toby Dalton of Carnegie and Michael Krepon of Stimson laid out four such demands. The most important one was a call to limit Pakistan’s production of short range missiles and tactical nuclear weapons.

The other three are a separation of Pakistan’s civil and military nuclear programmes, reduction or cessation of the production of special nuclear material, and a signature on the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty without waiting for India to do the same.

These terms outlined by Dalton and Krepon may not necessarily be the ones being discussed at the official level; but they certainly give Delhi a sense of the new approach in Washington.

On the face of it, the terms of the deal with Pakistan are somewhat different from those that India had won from Washington in 2005. That in itself will make it a hard political sell in Pakistan, which has always insisted on ‘nuclear parity’ with India.

The clamour for parity was expressed in its demand for a bilateral nuclear restraint regime with India. Delhi, of course, is unlikely to ever accept either parity or a regional restraint regime.

Pakistan may also find it more difficult than India to separate its civilian and military programmers that are so tightly bound.

Further, it is not clear why Pakistan would accept what have been called ‘brackets’ on its nuclear arsenal in return for access to civilian nuclear technology. After all, Pakistan has already broken through the global nuclear blockade with the help of China.

Beijing, which found it difficult to accept the India-US civil nuclear initiative but could not derail its implementation, has in clear violation of its nonproliferation commitments, been building new nuclear reactors in Pakistan.

The quest for nuclear parity has only been one important theme of Pakistan’s atomic diplomacy. The other is Jammu and Kashmir. Since it acquired nuclear weapons in the late 1980s, Pakistan has sought to leverage them to alter the political status quo in Kashmir.

That of course completes the vicious circle that has long complicated the triangular relationship between India, Pakistan and the US. Pakistan’s friends in Washington seem to think that they can square this circle with the help of Beijing. That might make matters a lot worse than they are today.

*The author is a Distinguished Fellow at Observer Research Foundation, Delhi and the Consulting Editor on foreign affairs for The Indian Express

Courtesy: The Indian Express, October 12, 2015