When Ping-Pong Saved The World – OpEd

By Caleb Mills

The fault of statesmen will always be that they take themselves too seriously, needlessly complicating problems that could easily be solved with human genuineness. And no, you don’t necessarily need to seek that out through a state dinner or big dramatic international conference of nations. As Chinese sportsman Zhuang Zedong showed the diplomatic world, all you really need is a good heart, a tank full of gas, and directions to Tokyo.

The story begins in Nagoya, Japan, a manufacturing and shipping hub located in central Honshu, the site of the 1971 World Table Tennis Championship. Teams from all over the world flew into the old Asian city to compete in a series of games that would not only display the healthy competitive spirits between the players, but also a lineup of rather unhealthy geopolitical grudges. But it’s difficult at times to remember that back then, that was the normal state of international relations. The anxious realities of the Cold War had invaded every single aspect of the lives of its participants, from the classroom to suburbia. The concept of absolute destruction threatens everything absolutely, equally. Even ping-pong couldn’t offer refuge.

In today’s political climate, we don’t know what a crisis feels like. We know what it’s like to look at our CNN app or plop in front of the evening news to hear the tales of growing storms far away from our secluded state of security. We are closed in, separated, disassociated from struggles we do not experience. Our worst form of distress is paranoia, beset by watching the trauma of others; we immediately think of ourselves. But the fears stoked by the Cold War didn’t originate from the fearmongering views-motivated script that David Brinkley would read out every night. They were in fact very real, and touched all of us. Which is why it’s all the more surprising that the Chinese ping-pong team’s captain would potentially risk an international incident by inviting a stranded U.S. player to hitch a ride with them to the tournament.

China had historically pursued a policy of isolationism when it came to foreign policy. Some of the only people who ever got to see more than their little slice of the Orient were sports players like Zedong. Teams were told not to socialize with their competitors.

But when American Glenn Cowan nervously stumbled onto the bus and took a seat, Zedong couldn’t help but feel sorry for the stranded player. So, he got up from the back of the bus and presented Cowan with a picture of a Chinese mountain scene, a gift to the newcomer to make him feel welcome. “Even now,” Zhuang recalled 35 years later, “I can’t forget the naive smile on [Cowen’s] face.” Cowan, who only had a comb in his bag, hesitantly replied, “I can’t give you a comb. I wish I could give you something, but I can’t.” But the two still hit it off, and Zhuang took a seat next to Cowan. An invitation was given and accepted that shocked the world: the U.S. team would officially visit China for a series of competitive matches.

Zhuang would later say more about the encounter during an interview with media mogul Chen Luyu in 2002. “The trip on the bus took 15 minutes, and I hesitated for 10 minutes. I grew up with the slogan ‘down with the American imperialism!’ And during the Cultural Revolution, the string of class struggle was tightened unprecedentedly, and I was asking myself: “Is it okay to have anything to do with your number one enemy?’”

Time called it “The ping heard round the world” and nothing could’ve been truer. However, the Chinese Department of Foreign Affairs wasn’t so receptive to the idea of bringing American athletes to the mainland and refused to honor the invite. It took Chinese Primer Mao Zedong’s direct intervention to get the Americans to Beijing, and even he was apparently hesitant. Speaking at the University of Southern California in the fall of 2007, Zhuang said of the intervention, “[Mao] told us that friendship was number one and sports and ranking were number two.”

Neither country was certainly looking for friendship, but they both had political climates that yearned for some sort of thaw. President Richard Nixon might have been a stalwart Republican, but he wanted peace just as badly as the liberal hippies parading around the Washington Monument. Nixon realized his top foreign policy goal needed to be neutralizing China’s role as an active political combatant, or at least soften it. And the Chinese were having their own problems with their supposed Russian allies and knew an American thaw, if not at least beneficial to their meager but growing economy, would show the Russians that Beijing had more than one option at the diplomatic table.

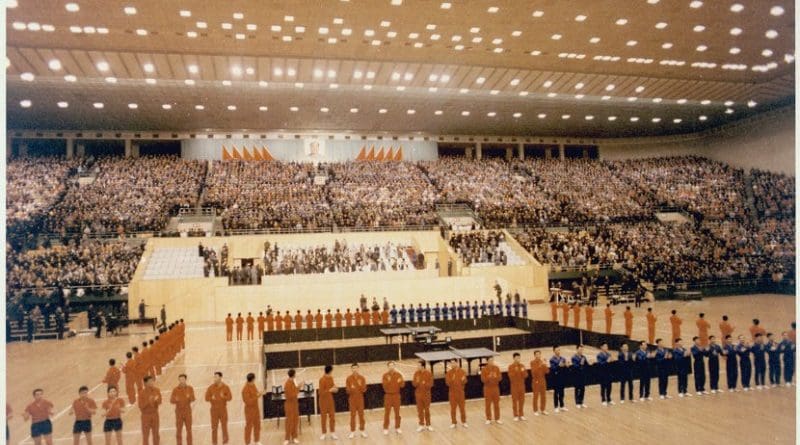

The team’s arrival hailed the first time an American delegation had set foot in China for two decades, and its success set the stage for Nixon’s China visit, which reshaped the international political system for the next century. America eventually lifted the trade embargo; China gained enough support from US allies to get a permanent presence in the UN; and the Shanghai Communique set forth the blueprint for modern Sino-American relations. The United States and China had both been seeking out an avenue with which to pursue a de-escalation of tensions, but after all the fancy gimmicks and State Department tricks had failed, the kindness of a single man saved the world from another decade of passive aggression and potential devastation.

There’s an array of things that could’ve wrong on that bus. The language difference could’ve stopped the two sportsmen from effectively communicating, a misinterpretation of words could’ve been taken as a slant against the other, or Zhuang Zedong could’ve simply shrugged his shoulders and stayed in the back of the bus.

We find ourselves today surrounded by challenges molded by mistakes from the past. But in spite of this, we have the opportunity to find that long chased peace in places like North Korea and Iran, and while it’s undoubtedly important to forge connections using traditional diplomatic means, it’s imperative not to forget the human element of a foreign policy debate. Whether it’s sports, books, or politics, we can find ways to see the best in people. Enemies are temporary if you want them to be.

Maybe we don’t need President Trump to fly to Tehran to meet with President Rouhani, or Secretary of State Pompeo to shake hands with Kim Jung-un in Pyongyang. Maybe all we need is a friendly game of hoops at the Georgetown YMCA. Sounds naive? Perhaps. But the human spirit is drenched with improbable dreams. So let’s chase one.

The opinions, beliefs, and viewpoints expressed by the authors are theirs alone and don’t reflect the official position of Geopoliticalmonitor.com or any other institution.