Churchill, Culture Wars, And The Flicks – OpEd

By Published by the Foreign Policy Research Institute

By Jeremy Black*

(FPRI) — Culture wars have been more apparent in the United States than the United Kingdom in recent decades, possibly because the nature of class-based politics is more explicit on the Left with the British Labour Party. Moreover, despite the efforts of Margaret Thatcher (1979-90), the Left has long enjoyed a dominant position in the universities, the BBC, the Church of England, and the other bastions of liberal corporatism. This situation led to a presentation of national history in which the traditional approach was alternatively trashed or neglected. Indeed, the prominent Conservative politician Michael Gove wrote in 2007 in response to the film Elizabeth: The Golden Age:

I can’t think of any major motion picture since 1969 (the Battle of Britain) in which this country and those who fight on its behalf were paid the compliment of being depicted as good guys, whom history vindicates. . . . What makes it worth celebrating is that it records England historically, as on the side of liberty. Cate Blanchett is magnificent, and her speech [as Elizabeth I in 1588] when she rallies England’s defenders in the cause of freedom against the looming shadow of the Inquisition is a proper and straight interpretation of our past that accurately captures the ideological attachment to liberty which has been the defining factor in our distinctive progress over time.[1]

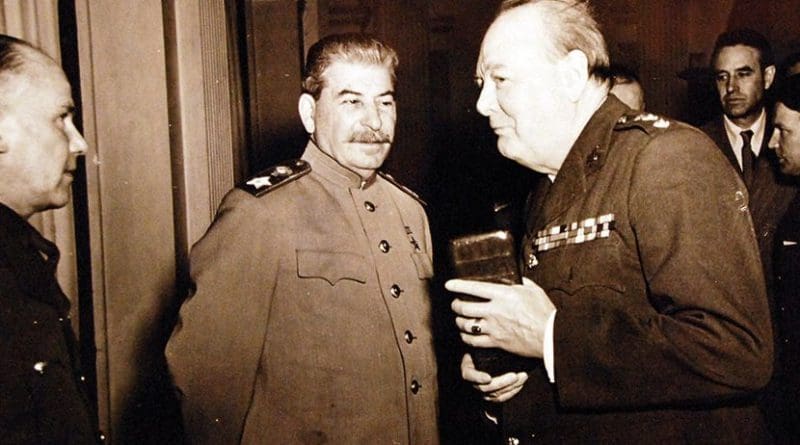

Gove was to be repeatedly trashed by the Left when, as Secretary of State for Education, he presided over a very modest redrawing of the “National Curriculum” for History.[2] In part, the critique was an aspect of the broader-ranging attack on the national past that has been especially strong of late, as evinced in particular in the discussion of the British Empire. Winston Churchill has long been a figure of criticism. As a journalist pointed out in response to the new film, Darkest Hour, “There is something about the magnificence of his central achievement at a defining hour in 1940 that seems to drive Britain’s alleged intelligentsia round the bend whenever it reappears as a theme in popular culture.”

This approach draws on a longer critique, as in George Orwell’s The Lion and the Unicorn (1941): “In the general patriotism of the country they form a sort of island of dissident thought. England is perhaps the only great country whose intellectuals are ashamed of their own nationality.” The recent release of films such as Dunkirk and now Darkest Hour, however, suggest a subtle turning of the tide.

Churchill came to the fore in May 1940 because Chamberlain was not acceptable as the head of the coalition government that appeared necessary in the developing international crisis. Churchill was controversial, indeed regarded by many as a dangerous maverick, but he conveyed determination, had war experience, and whatever the reservations of some generals, gave the impression he could do the job. He certainly provided the necessary backbone when the fall of France hit the new government hard, leading to a major crisis of credibility. Churchill was convinced that Hitler was untrustworthy and a mortal threat to Britain and the world. There was to be no alliance of expedience with Germany comparable to the Nazi-Soviet Pact of 1939 or (very differently) American isolationism, which helps explain why the British account of the politics of their war record is justifiably a good one. Instead, Churchill’s determination led him to withstand pressure for negotiation and steadied both government and nation for the challenges of the summer and autumn of 1940, notably the German air-assault. He was able to explain the need to fight on and the purpose of doing so, although, in practice, waiting for something to turn up was important.

Darkest Hour, and, in particular, Gary Oldman’s portrayal of Churchill, have deservedly won some very favorable reviews for their dramatic portrayal of those decisive days. How does it measure up for an historian? Peggy Noonan underlined the importance of this question recently in the Wall Street Journal, where she identified historical inaccuracies in the recent television series, The Crown, and the film The Post, and worried about how dramas that bend historical truth can warp public understanding of history. Her warnings are well taken, and there are indeed a few problems in Darkest Hour, notably the fictitious scene of Churchill taking the “tube” (London Underground railway) and seeking a reassurance he receives from the public about the merit of fighting on. George VI’s doubts about Churchill are also played up for dramatic effect.

Nevertheless, the film captures Churchill’s historical accomplishment in overcoming the British political crisis that continued even after he became Prime Minister. Interest within the government in negotiating peace with Hitler via Mussolini was indeed strong until the latter declared war on Britain and France on June 10. Viscount Halifax, the Foreign Secretary, favored negotiations, while in the Commons, R.A. Butler, the Under Secretary of State in the Foreign Office (a post made more important because Halifax was in the Lords), was willing to consider negotiations and was not moved to a less contentious post until 1941.

The film, however, links Neville Chamberlain and Halifax, and underplays the role of David Lloyd George in the political crisis, which is both too critical of Chamberlain and too charitable to Lloyd George. A Liberal who became Prime Minister in 1916 during the crisis of the First World War, and served until 1922, Lloyd George was initially critical of Hitler, referring to Nazi political and religious repression as “a terrible thing to an old Liberal like myself.”[3] By 1940, however, Lloyd George was convinced that Churchill was a fool to fight on. A turning point for him was a 1936 invitation to Germany from Hitler, who had praised Lloyd George’s wartime leadership in Mein Kampf. Their final meeting closed with the former Prime Minister urging Hitler, “the greatest German of the age,” to visit Britain, which Hitler wanted to enlist against Communism. In 1940, Lloyd George’s hopes of office after Chamberlain’s resignation were thwarted due to the latter’s opposition, and when, on June 4, he was at last offered a Cabinet post by Churchill, he refused to serve as long as Chamberlain remained in office. Chamberlain saw Lloyd George as a potential Petain, another figure from the previous world war. Regarding Churchill as his junior, he felt he had a better claim to lead the country. That October, Lloyd George said he would enter office when “Winston is bust.”

No longer Prime Minister, Chamberlain had become one of the five on the War Cabinet and served as Lord President of the Council and as leader of the Conservative Party until he resigned on grounds of ill health in September (he died in November). The film thus does not do justice to Chamberlain’s opposition to Lloyd George, or to his refusal to use his position to overthrow Churchill.

What about Mike Huckabee’s tweet comparing Churchill with Trump, and Chamberlain with Obama: “We have a Churchill”? All comparisons are of course problematic, but there are some instructive items. The USA may well be on the eve of more threatening confrontations in East Asia, and may even face an unprovoked assault as in 1941. Britain, in May 1940, constructed an effective coalition government that lasted until after Hitler’s defeat. As well as succeeding Chamberlain as Party leader, Churchill was able to lead a coalition government. I do not assume that Huckabee is predicting such political ambitions (or skills) on the part of Trump. In 1940, Churchill also became Minister of Defense and, albeit to the anger of many military leaders, including the Chiefs of Staff, he acted effectively in this role. Churchill had relevant experience and certainly more than current or recent leaders, American and British.

The film’s focus, however, is on leadership and that can entail a willingness to be unpopular. Though very different characters, both Churchill and Trump show that. Yet, it is also necessary to be able to move forward effectively and to win both domestic and international support to that end. Churchill displayed that skill. Let us hope that America’s leaders, whatever their politics, can do the same.

About the author:

*Jeremy Black’s books include Rethinking World War Two, Air Power, and Combined Operations.

Source:

This article was published by FPRI

Notes:

[1] Michael Gove, “A drum roll, please. Britons are back as heroes at long last,” The Times, November 6, 2007, section 2, p. 8.

[2] For the record, I was a member of the Advisory Committee, and Gove is a friend.

[3] A. Lenton, Lloyd George and the Lost Peace. From Versailles to Hitler, 1919-1940 (Basingstoke, 2001), p. 103.