Trans-Himalayan Economic Corridor: Nepal As A Gateway – Analysis

By Observer Research Foundation

By Madhukar SJB Rana

Historically, Nepal has prospered, until the advent of the East India Company into the subcontinent, as an economic corridor and a civilizational bridge between adjoining northern India and Tibet. Following the calamitous loss by Nepal in the Anglo Gurkha War of 1814-16, it was territorially reduced in size by around 33 percent and its prevalent national ‘geo-psychology’ was transformed from an emerging Himalayan empire aspiring to be an economic and cultural bridgehead between India and China to simply of a “yam between two boulders.” Subsequently, it sought to look inward and close its doors to the outside world. This paper attempts to examine the idea of a Trans-Himalayan Economic Corridor (THEC) centred on Nepal. It is based on the firm belief that a THEC can profoundly transform the entire southeastern Himalayan subregion and the Ganges Basin – where most of the world’s absolute poor and deprived peoples now live – with benefits for all.

The south-eastern Himalayan subregion and the Ganges Basin need a big push in infrastructure investments coupled with far more robust annual economic growth rates to meet the challenges posed by its poverty, mass unemployment and massive underemployment of its human capital. As also, risks arising from natural disasters, climate change, global warming, and not least, water, food, health and energy security threats. Amidst the development and security challenges faced by the Himalayan subregion, the emergence of Asia as a world economic fulcrum, led by China—and a China that is in the throes of its “look west” national strategy offers grand opportunities to deal with these challenges.

The Southern Silk Road (SSR)

The SSR existed historically.[1] It commenced in Yunnan connecting it to Myanmar, India, Nepal and Tibet with a loop back to Yunnan. It is believed that this Silk Road was at its peak in the 13th century with the Mongol Dynasty flourishing; but declined in the 14th century on account of the isolationist policies followed by the Ming Dynasty. It was also called the Tea and Horse Road. However, this has received scant attention. It was, if you like, the predecessor to the Bangladesh-China-India-Myanmar Economic Corridor (BCIM-EC).[2] Yunnan is planned as bridgehead for inter-regional and subregional integration with Myanmar, Bangladesh, eastern India just as China’s Xingjiang is to Central Asia, Afghanistan and Pakistan in reviving the more popular northern Silk Road.

Imagine the prospects, the “One Belt, One Road”[3] or OBOR extended to South Asia by executing the BCIM Corridor and, furthermore, reviving the SSR to connect the Tibetan Plateau to Nepal and extended it into Bihar in northern India and beyond by both road and rail and, even later on by energy grids. It is, indeed a vision of grandeur where all of Asia— North, Central, South, East and West— will be connected by China to Europe and Russia by road and rail. Even so, integration possibilities with Tibet and the Sichuan Province need to be studied and explored for Bhutan, Nepal, North India with and without the extension of the BCIM Economic Corridor with these new destinations.

The BCIM corridor could be extended to Nepal to realize the BBIN vision[4] of Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi. It will also permit India’s Northeast to be connected to another Himalayan corridor through Nepal by land and the potential to have the BCIM countries connected in the near future to the railway network of China with the Lhasa-Kathmandu-Lumbini railway. Such a rail link would make it possible for Bangladesh, Bhutan and Nepal to trade by land with Pakistan and Afghanistan too.

Trans-Himalayan Economic Corridor

Nepal has made it clear that it wishes to act as a Himalayan land-bridge between Central and South and Southeast Asia. Thus it would welcome the ‘southern OBOR’ to be connected with Europe and also welcome the extension of the Chinese Railway into Kathmandu and Lumbini, the birth place of Lord Buddha. Nepal’s King Gyanendra raised the idea of Nepal as a ‘transit economy’ when he proposed this at the Second South-South Summit in Doha in 2005.[5] This strategic policy was well incorporated in the country’s Annual Budget of 2005 with this author, in his capacity as Finance Minister then. Further, the king asked this author to lead a delegation to Lhasa and Beijing to discuss matters about opening more routes on the China-Nepal border for bilateral trade as well as express Nepal’s interest that it would like to see the extension of the Beijing-Lhasa train to the Nepalese border and on to Kathmandu.

Five years later since the idea was first announced, Nepal’s Maoist Prime Minister Pushpa Kamal Dahal (Prachanda) coined the concept “trilateral strategic relations” involving India, China and Nepal in 2010. He believed that this concept would “address concerns of all three at once”. In 2012, Prachanda, in his capacity as Chairman of Nepal’s Maoist Party, was reported to have signed a $3 billion deal with China-sponsored Asia Pacific Exchange Cooperation (APEC) to develop Lumbini as a world class religious tourism and cultural city.[6] The envisaged project would enormously benefit China, India and Nepal, especially Bodh Gaya, Sarnath and Kushinagar in Bihar. Maoist leader, Babu Ram Bhattarai, while addressing the Parliament on becoming Prime Minister in 2011 stated that, henceforth, Nepal should act as a “friendship bridge”[7] and dispense with the notion that it is a “yam between two stones”.

Arguably, India will prefer Nepal as the Himalayan bridge economy for national security reasons, pending non-settlement of China-India border disputes. Hence, it is of utmost importance for Nepal to take advantage of the Mid-Hill-East-West Highway and link it with Uttarakhand and Sikkim to create a Greater Himalayan Economic Corridor by extending the BCIM Economic Corridor to Bhutan and Nepal. Nepal needs to call for the revival of the SSR as a major new diplomatic thrust with China to establish a Trans Himalayan Economic Belt. It should be underscored here that China has already urged India to join this belt.[8] China foresees the Himalayas as the next frontier for global resource management and conservation particularly in (a) the wake of climate change and global warming and the fact that it serves as the Asian water tower for 4-5 billion peoples and (b) the yet unknown mineral deposits in the Himalayan subregion. Already it is reported that Afghanistan is endowed with $1 trillion of newly found mineral deposits.[9]

It was projected that trade through Sikkim’s Nathula Pass would be $ 48 million by 2007 and will rise to $ 527 million by 2010.[10] As it turns out, not more than $ 5-6 million of border trade actually occurs. This suggests that security and defense politics takes precedence over geo-economics. With such vast potentials, Nepal was quick to declare, in 2005, its interest to serve as a ‘transit economy’, which was eminently possible as per the Treaty of Transit with India. Nepal’s exports to Tibet rose from $ 5.8 million in 1991 to $ 33 million in 2005. A 10 percent of the projected traffic through the Nathula Pass, diverted to Nepal, would be highly significant for Nepal’s balance of trade with both China and India accruing from the transit fees.

It would also provide huge scope for the transit corridor from Birgunj, on the Indian border, to Tatopani on the Chinese border as an opportunity to invest in modern warehouses; container depots; material handling equipment; weighing bridges; inspection and testing laboratories; weighing bridges; repacking logistics centres as well as provide modern living and eating amenities for truckers, agents and freight forwarders. It was planned to also open many more North South Riverine transport corridors to make it possible for traffic in transit directly from West Bengal, Bihar and Uttar Pradesh in northern India.

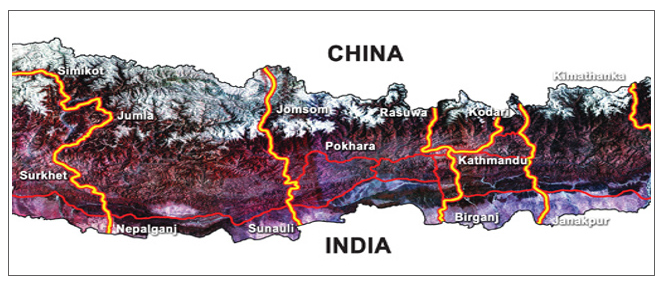

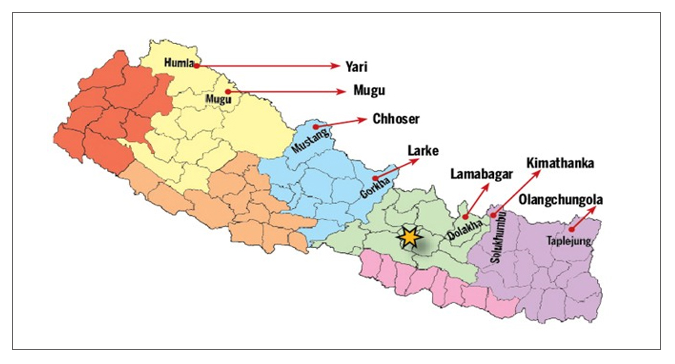

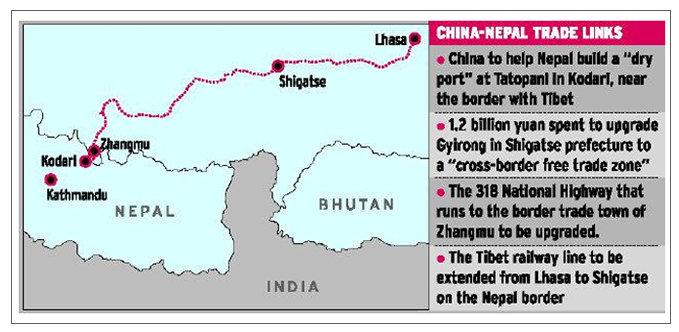

China was most keen to develop outlying town of Tibet Autonomous Region (TAR). Beijing-Lhasa railway was extended to Shigatse in 2014,[11] TAR’s second largest city. Further, it was felt desirable that the TAR develop Zhangmu, connected to the Arniko Highway, as its premier port of entry into South Asia. The Nepal government has decided to ask China to expand the Arniko Highway as a 4 lane highway connecting Tatopani to Kathmandu.[12] It is the closest and fastest route to Shigatse. Additionally, seven trading points will now be opened up with Tibet – Yari, Mugu, Choser; Larke, Lamabagar, Kimathanka and Olangchula. In all, there will be a minimum of nine Trans-Himalayan trading points with China.

The TAR authorities were also giving priority to develop its second largest border entry port at Gyirong for both trade and tourism. As of 2012, it is completed, with an investment of $ 190 million, establishing a 44.5 sq km infrastructure facility with a logistic park; storage processing centre; joint customs post and a tourist centre. Transport corridors are not just confined to highways but also embrace airways, waterways, electricity grids, pipelines and gas lines; optic fibre lines and railways. Unlike Transport or Transshipment or Transit Corridors, Economic Corridors are more preferable as more value addition takes place in the economies through production as a result of the transportation and distribution infrastructure. This happens from the backward and forward linkages created and the subsequent multiplier impacts.

Economic Corridors must seek integration of subregions through value-additions and supply chain innovations. For this to happen infrastructure in the form of highly capital intensive SEZs, EPZs, FTZs, EPVs, Industrial Parks must be created. To have maximum benefits it would be ideal to revive the subregional SAGQ Framework and link it with the BCIM to integrate the eastern seaboard of the subcontinent with Mekong region in the framework of BIMSTEC.

Five possible economic corridors are possible in Nepal. They are:

- Karnali Economic Corridor: Can integrate Far West Region of Nepal with Tibet, Kumaon, North UP (Lucknow Growth Axis)

- Gandhak Economic Corridor : Can integrate West Region of Nepal with Tibet, North UP (Gorakhpur Axis)

- Bagmati Economic Corridors: Can integrate Central Region of Nepal with Tibet and Bihar (Patna Growth Axis)

- Kosi Economic Corridor: Can integrate Eastern Region of Nepal with Tibet, Sikkim, Darjeeling, Doars (Siliguri Growth Axis).

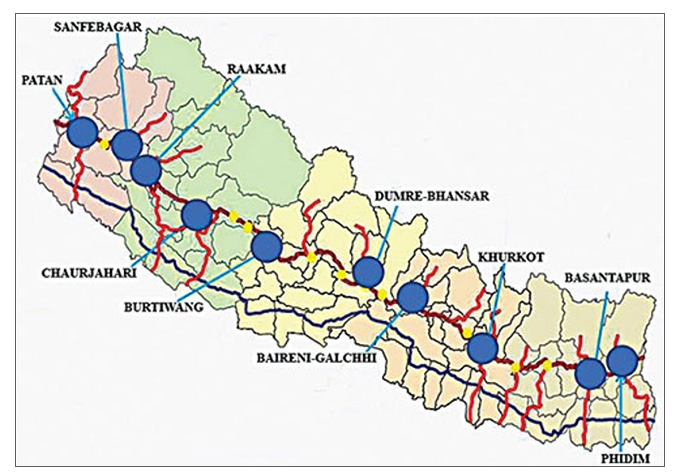

Another development of strategic significance for the Greater Himalayan Region is the construction of the Mid-Hill-East-West-Highway of Nepal with due emphasis to ten model town developments along the way to serve as growth centres. The new strategic highway will be 1176 km long. It may be shortened to economize on costs, which is estimated at Rs 43 billion (Rs 10 million per km and Rs 20 million per km black topped). It serves 24 districts in 215 VDCs and 7 million people or 25 percent of the total current population. The Eastern section will traverse Chisobhanjyan-Ganeshchowk-Myaglung-Basantpur-Hile-Bhojpur-Diktel-Ghurmi-Dulikhel-Kathmandu-Pokhara; and the Western Section Pokhara-Baglung-Musikot Border-Rukumkot-Musikot-Chaujahari-Dailekh-Lainchaur-Saijula-Silgadi-DSatbanjh-Jhulaghat.

The Nepali government’s plan to establish ten model cities along the mid-hill highway is observed as a special attraction. Proposed cities are Phidim (in Panchthar district), Basantapur (Terhathum), Khurkot (Sindhuli), Baireni Galchhi (Dhading), Dumre (Tanahun), Burtibang (Baglung), Chaurjahari (Rukum), Rakam (Dailekh), Sanfebagar (Achham) and Patan (Baitadi). The significance of this highway is, other than halting migration to the plains, it will make possible ‘off season’ export of crops to India and China from its ecological diversity. Phidim and Baitaidi are entry points to Sikkim and Uttarakhand respectively which, if connected, will open a ‘new horizon’ for Himalayan subregional cooperation extending to Himachal Pradesh for the creation of a Green Himalayan Economy.

It is hoped that these three Himalayan entities will join hands to plan various Green Missions keeping sight of the broader Asian and world markets. Such Green Missions could concentrate on specializations in different horticulture, floriculture, medicinal herbs products and services through intensive cultivation of selected crops and their processing and global marketing and branding. Joint efforts in development, promotion and marketing in the field of religious and adventure tourism is another potential especially in setting of a World Spiritual City in the Kailash Mansarovar region of Tibet. Huge scope for joint venturing and creation of Himalayan MNCs exist to take full advantages of the markets in China and Northern India in the areas of cement, pulp and paper manufacturing , medicinal herbs and pharmaceutical, iron and steel, fertilizer, and tourism resorts. It is staggering what the potential for development and growth that is possible from this Trans Himalayan Economic Corridor when one considers that the total population of the area could be more than 200 million without UP and nearly 400 million with UP if we can form this trilateral Trans Himalayan Economic Corridor involving China India and Nepal. The Economic Corridor can also be envisaged by networks such as air ways, water ways, ferry services, energy and gas grids.

Should the BCIM Economic Corridor be extended to Bhutan and Nepal one can expect two dynamic developments, namely (a) the Kosi River Basin Economic Corridor in the near future. There is the Asian Development Bank’s (ADB) SASEC subregional programme and (b) a Kathmandu Haldia Transport Corridor which if it materializes will restore the pride of Kolkata as the grand Asian metropolis: that it was during the British Raj—but this time connected by sea as well as land to the rest of the world.

When Nepal seeks to be a transit economy or a bridgehead economy, it should be clear that to serve as a change agent for the realization of the once dreamt Asian Community of the late 1940s and now being revived as the ‘Chinese Dream’ with the emergent Renaissance of Asia. Asian Community needs air, land, inland water and sea connectivity – including cyber connectivity. While such connectivity is necessary they are not sufficient. Both conditions need to be met for what could be called ‘Total Connectivity’. This means markets must be connected through bilateral FTAs. As we know FTAs will need to be supported by BOT oriented investments to create ‘production complementarities’ along with the ‘trade complementarities’ rendered by FTAs. Production complementarities may be created through creation of supply chains in select products or sub sectors and also through relocation of the highly labour intensive industries into Nepal by China (e.g. leather and leather products, textiles and garments, locks, etc.)

Market connectivity must be supported by institutional connectivity to realign macro and mega policies which requires connectivity between public and private sectors and not least municipal governments. Financial and legal connectivity is another area where we have to connect the money and exchange regimes that may have to innovate with new instrumentalities like stocks, bonds as well as barter like trade over infrastructure in each territory. This way we have a trade and exchange regime that uses national currencies while developing capital and bond markets too. Connectivity between municipalities is also important to understand local development plans to help municipalities integrate themselves with the OBOR/BCIM or THEC. Human capital connectivity is fundamental if we are to have all this connectivity not just for growth but also jobs. For jobs we need our human capital to be of the highest quality and in tune with the labour market demands. This calls for connectivity in the areas of science, technology education and R&D where we seek common standards and technical qualifications.

Conclusion

Political scientists look upon trilateralism as an impossibility, when trilateralism involves a triangular relations where powers are not equal. Economists look upon it as straight line or corridor spanning geographic borders to gain from the opportunities arising from their differential resource endowments and fiscal differentials because of comparative advantage or competitive advantage or manufacturing supply chains. How does one explain the movement of once imperialist Japan’s labour intensive manufactures – called flying geese – to Korea and Taiwan and, later, China and Southeast Asia. Also, it is misguided to think that small powers wish equal status in political terms so long as the economic benefits are mutual and, ideally, equitable.

Technology can change the face of the earth. It was so with the steamship in the medieval age. In the 21st century, it looks likely that technological determinism will be pronounced with the massive spread of high speed railways, at least in the Himalayan region. And thus usher in a new paradigm in international relations. The advent of the railway into Tibet and its borders in South Asia is a new factor; with all the force for change emanating through the so called ‘economic pull factor’ from the Tibetan plateau on its South Asian neighbourhood that could spread into the Ganges Basin. What explains better the interest of India to now opt for the BCIM Economic Corridor despite the traditional security risks of opening up its Northeast region to the outside world? Going further, it may be hypothesized that trilateral economic cooperation is more beneficial from a security perspective for big powers for the simple reason that security risks are curtailed in trilateralism when it engages strong buffer states (such as Nepal and Myanmar). This is why trilateralism is preferred to bilateralism by big powers.

The above arguments also lead us to conclude that precisely owing to economic and technological determinism, it is not necessary to have a common security agreement or understanding before trilateral cooperation can ensue. Non-traditional security threats are solid causes for trilateralism. Further, security agreements or understanding curtail the manouverability of the smaller powers from reaching out to extra-regional big powers which are strategic for their survival. Economic corridors are excellent confidence-building investments to deal with the emergent mega risks from the impending water security caused by climate change and global waning and the inevitability of complex disputes over riparian rights— upper, middle and lower.

Chinese scholars admit that for Xi’s ‘China Dream’, anchored on Silk Road and Route strategies, to succeed, innovations in international relations are eminently needed. So far, these ‘innovations’ are limited to creation of transport corridors and massive investments in the infrastructure necessary for the deserted corridors. This includes energy grids as well as communication networks to supplement the transport and logistics networks. Beyond this, Chinese scholars speak of cooperation in new frontiers such as, for example, human capital development. It recognizes how devolved planning and management of corridors can and should be by calling for institutional innovations such as formation of transporters, industrialists, traders forming alliances and creating ‘alliances between cities’ along the corridor and discovering networking mechanisms between these institutional platforms.[13]

Chinese scholars and planners must begin to visualize, at least, in its immediate neighbourhood, that what is important is not transport corridors but economic corridors leading to subregional integration of contiguous territories. Having said this, for the Himalayan subregion it must envision the rivers as the bedrock of subregional cooperation for harmonious development with peace and security uppermost in mind. It is, therefore, suggested that harnessing the Indus, Ganges and Brahmaputra Rivers in the context of a broader, macro level River Basin Development would be ideal for all partners for shared prosperity and sustainability. This would require that economic corridors focus on agriculture and agro-processing; forestry and forestry products; mining and mineral products; water resource engineering; construction engineering; S&T and R&D for creation of world class intellectual capital among others as priority areas.

To underscore, economic corridors are perfect tools for subregional co-operation through devolution of responsibility and authority to local bodies and communities. They need seamless connectivity by road, rail, waterway, rope way, grids etc. But, importantly, the markets must be integrated and supported by financial cooperation by local governments and banks with risks judicially shared by all the central governments.

Japan Rising 1950’s vision of an Asian Highway Network is being revived as it too wishes to promote its technology, knowhow and surplus dollars and invest in Asian infrastructure —perhaps in competition to China. This will be a welcome development for us in South Asia as we have greater choice over sources and projects. It also promises to benefit South Asia in another direction; namely, the possible development of Asian MNC that combine East Asian finance, technology and knowhow with South Asian labour for the construction of the mega infrastructure trans Himalayan projects to build connectivity and harness its vast water resources for water security, energy security, food security and riverine transportation. It must be said here that the momentum with which Trans Himalayan Economic Corridors assume shape and form will depend, critically, on the settlement of all bilateral boundary issues between neighbours.

This article was originally published in GP-ORF’s Emerging Trans-Regional corridors: South and Southeast Asia

[1] See “The Ancient Tea and Horse Caravan Road: The ‘Silk Road’ of Southwest China”, The Silk Road Foundation Newsletter at silkroadfoundation.org/newsletter/2004vol2num1/tea.htm

[2] The BCIM-EC is a four-nation connectivity initiative involving Bangladesh, China, India and Myanmar. See for instance Patricia Uberoi, “The BCIM Economic Corridor: A Leap into the Unknown?”, ICS Working Paper, November 2014 at http://www.icsin.org/uploads/2015/05/15/89cb0691df2fa541b6972080968fd6ce.pdf

[3] In 2013 Xi Jinping announced the “One Belt, One Road” initiative to revive the ancient silk roads. See chronology of the OBOR at http://english.gov.cn/news/top_news/2015/04/20/content_281475092566326.htm

[4] The Bangladesh, Bhutan, India and Nepal or BBIN is a sub-regional vision for economic integration. The first this towards this objective was achieve when the four nations signed a motor vehicle agreement for free movement in June 201. See “Forget SAARC, if Pakistan does not cooperate, India will come up with ‘BBIN’”, First Post, February 26, 2015 at http://www.firstpost.com/world/forget-saarc-if-pakistan-does-not-cooperate-india-will-come-up-with-bbin-2121773.html

[5]See full text of the address of at the Second South-South Summit, Doha, State of Qatar on 15 June 2005 available at http://www.satp.org/satporgtp/countries/nepal/document/papers/king_June05.htm

[6] “Nepal’s Prachanda inks Lumbini deal with Chinese NGO: Report”, November 8, 2012, Global Post at http://www.globalpost.com/dispatches/globalpost-blogs/india/nepal-prachanda-lumbini-china

[7] “Nepal to Act As Friendship Bridge Between India, China”,16 September, 2011, Outlook at http://www.outlookindia.com/newswire/story/nepal-to-act-as-friendship-bridge-between-india-china/735004

[8] Pradumna B Rana and Binod Karmacharya, “A Connectivity Driven Development Strategy for Nepal: From a Landlocked to a Land-Linked State”, ADBI Working Paper Series, Tokyo, No. 498, September 2014 at http://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/156353/adbi-wp498.pdf

[9] “$1 Trillion Trove of Rare Minerals Revealed Under Afghanistan”, September 4, 2014, Live Science at http://www.livescience.com/47682-rare-earth-minerals-found-under-afghanistan.html#sthash.LFSq94lU.dpuf

[10] “Nathu La beckons”, Frontline, Volume 23 – Issue 14, July 15-28, 2006 at http://www.frontline.in/static/html/fl2314/stories/20060728002603600.htm

[11]“Himalayan rail route endorsed”, China Daily, 5 August 2016 at http://usa.chinadaily.com.cn/business/2016-08/05/content_26361358.htm

[12] “Nepal to request China to expand Araniko Highway”, The Kathmandu Post, 9 November, 2015 at

[13] Shi Ze, “‘One Belt and One Road’& New Thinking with regard to Concept and Practice”, New Paradigm, Schuller Institute (no date and place) at http://newparadigm.schillerinstitute.com/media/one-road-and-one-belt-and-new-thinking-with-regard-to-concepts-and-practice/

Deep analysis about Nepal and china borders, possibilities of business to improve the economy. it is one of the best Gateway to rise the Nepalese economy but political leaders suffering from the lack of long term vision. Great article