Countering Left Wing Extremism: Need To Look Beyond Numbers – Analysis

By IPCS

By Dr Rajat Kumar Kujur*

It has been over 50 years, and the Maoist movement in India is still not showing signs of withdrawing or weakening. Undeniably, at present, the movement is hard pressed by new challenges and it no longer inspires the buoyant optimism it did during the 1960-70 period. Yet, simultaneously, it is also true that the government has not been able to fine tune its strategies and policies to effectively deal with what was described by a former Indian prime minister as “the single biggest threat to India’s internal security.” Going forward, it is important to glean lessons from past experiences in order to counter left wing extremism (LWE) comprehensively.

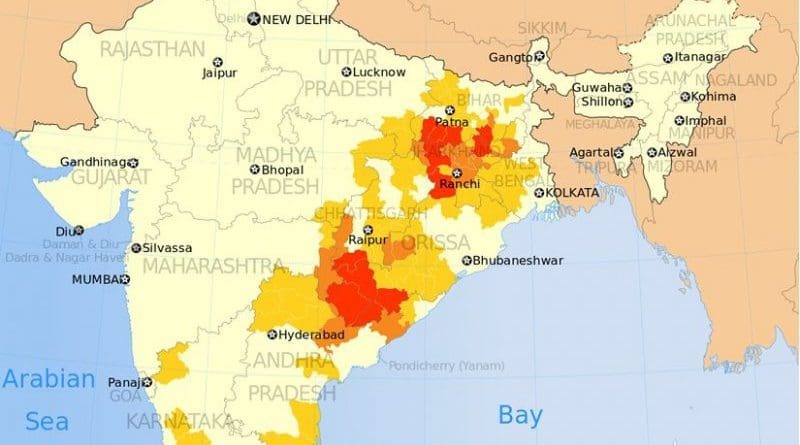

Since 2015, the Union Government has been following the National Policy and Action Plan to tackle the Maoist insurgency. According to the Ministry of Home Affairs’ (MHA) data, the numbers of districts affected by Maoist violence has reduced from 106 in 2017 to 90 in 2018. Similarly, the numbers of worst-affected districts reduced to 30 in 2018 from 36 in 2017. Security forces killed 232 Maoists in 2018 while the number was 150 in 2017. Going by those statistics there seems to be no doubt about the success of the government’s counter-Maoist strategy. However, while dealing with a problem like LWE one needs to look beyond the numbers as well. Numbers are always deceptive in a conflict situation because they only portray half the truth.

As per official data, while the numbers of attacks on security personnel may have reduced in past few years, during the same period, Maoists also demonstrated their ability to carry out fatal attacks on security forces. Unfortunately India’s counter-Maoist strategy is yet to find answers to the Maoists’ use of landmines that cause massive damage to the life and morale of the security forces. Indeed, a lot of coordination between state police and central paramilitary forces operating on the ground is visible now. However, what is missing is real time intelligence. In a conflict like LWE that India faces, it is not high tech intelligence but human intelligence that holds the key.

Coercion or otherwise, it is local support for the Maoists that makes it difficult for the security forces to procure accurate information about the insurgents. On the other hand, Maoists get information on security forces’ logistics through villagers. Additionally, Maoists are extremely familiar with the topography of the forest land and the hills. Meanwhile, security forces find it difficult to keep pace with the Maoists as they fall short on accurate knowledge of the terrain. Given the situation, it is time for the local police forces to redefine their role in the counter-Maoist operations.

In 2018, Maoist penetration into India’s urban centres emerged as the greatest challenge for the government. The Maoists have carved the “Golden Corridor” (Pune-Mumbai-Ahmadabad), “Ganga Corridor” (Delhi-Kanpur-Patna-Kolkata), and the “Tri-junction” (Chennai-Coimbatore-Bengaluru) for their urban operations. Maoists have also formed urban cells in the industrial belts of Raipur, Durg, Surat, Faridabad and Bastar. They are making steady inroads into the many of India’s semi-urban centres. While the Maoists seem to be preparing for the next stage of the ‘People’s War’ i.e. encircling the cities, the government is busy counting its success from the rural war fields.

An important development of 2018 that could lead to a perceptible change in the course of the Maoist Movement in India is the stepping down of Ganapathy and elevation of Baswaraj as the general secretary of the Communist Party of India (Maoist). Known to be extremely tech-savvy and equally strong in his ideological commitment and military craft, Baswaraj is a fervent advocate of the Tactical Counter Offensive Campaign (TCOC) to blunt counter-insurgency measures. His experience of leading the People’s Liberation Guerrilla Army (PLGA) could result in a possible escalation of violence in the coming days.

Undoubtedly, the Indian government’s multi-pronged strategy in the areas of security, development, and community empowerment, have begun to show results. It is also a fact that CPI (Maoist) is experiencing one of its worst leadership crises. However, it would be useful to remember that the Maoists have survived similar situations in the past. When several analysts wrote off the Movement following the arrests of Charu Majumdar and Kondapalli Seetharamaiah in 1972 and in 1993 respectively, the group proved everyone wrong with its resurgence.

At present, the government evidently has an edge over the CPI (Maoist) but that should not lead to unrealistic assessments. Success is not always dependent merely on numbers. And the success of the counter-Maoist strategy depends much on winning the hearts and minds of the people who are yet to realise their independence. It is not just to reaffirm India’s sovereignty over its own territory; more than that, it is essential to make people realise that the sovereign power belongs to them.

Strengthening of institutions for proper implementation of government programmes is much more essential than formulation of ambitious development plans and programmes. Raising new battalions for security agencies is important but preventing youth, children and women from joining the Maoist fold is equally important. With a new general secretary at the helm of affairs at a time when general elections are fast approaching, and changes in state government leaderships in various Maoist infested states, it is certain that the CPI (Maoist) will change gears in 2019. The government of India must wake up to the winds of change in order to prevent any future ‘Spring Thunder’, for India does not need it.

*Dr Rajat Kumar Kujur is an Assistant Professor at Sambalpur University, Odisha, India.