On Cruelty And Capital Punishment – OpEd

Why some audiences could do with understanding a little more, and condemning a little less.

Death by stoning, the gruesome public burying of a culprit up to the waist or neck and stoning them continuously to prolong the pain is a rarely applied punishment that by any measure constitutes a minuscule portion of the Islamic penal code.

Regardless of its moral justification be it closure, deterrence or retribution, the image permeates into the minds of many as backward, medieval, morally repugnant and full of needless suffering that’s inconsistent with modernity — a notion portentously referred to as a rupture from the past.

It is often advocated that by demolishing the law in countries where it can still be administered as in the Islamic Republic of Iran – a nation of 70 million that has applied it in two or three cases in the last seven years – will make headway for them to join the family of exemplary states that respect human rights.

But the condemning of the laws of another country as unjust because they’re inconsistent with your own is not only wrong, but also ignorant of the values and customs to which others parts of the world adhere.

And in more shrewd discernment, the underlying reason for the condemnation is not about the hideous process of stoning itself, nor is it about arguing that life- without-parole is more humane that capital punishment.

It is something far more closer to people’s consciousness that they’d care to convey: the notion of ‘cruelty’ in relation to capital punishment.

Cruelty is not absolute

All forms of capital punishment are cruel. It really would not make a blind bit of difference whether you legally authorize killing someone by firing squad, by gas, by guillotine or by public beheading — it’s still cruel.

What is far more important is acknowledging that ‘punishment’ is different to ‘cruelty’ and that cruelty is not an absolute notion.

It is more accurately a notion that is cultural or societal-relative because an action that is considered ‘cruel and unusual’ in one society can quite easily be perceived as different in another.

The United States – where 2,902 prisoners have been on death row since October 2016 – is the most advanced, innovative and powerful nation on earth, yet in several of its states they have executed, and continue to reserve the right to execute, individuals by electric chair.

This is the process of strapping a person to a specially built wooden chair, subject them to jolts of excruciating electric current intended to firstly pass through their head leading to unconsciousness and brain death, before going on to essentially cook the vital organs of the body and finishing off the job.

At the same time in Singapore, an island city-state that has the third highest GDP Per Capita in the world, the top-ranked education system for children and is designated by the UN as one of the world’s least corrupt nations on earth, continues to hang people through a system of variable long drops.

This is the act of calculating the exact height, length and weight of a prisoner, dropping them through a trap door to a pre-determined distance so that they’re subjected to instant unconsciousness and ultimately death by a breaking of the spine through a separation of the second and third vertebrae.

That the prisoners may be rendered to uncontrollable grimacing and violent shakes due to the spinal reflexes involved in hanging – a corollary of the time it can take to sever the nervous system in order to prevent pain – is irrelevant.

Is it not unfair to say the former is acceptable, but the latter is cruel?

Even if you advocate for capital punishment to be administered in a way the American Eighth Amendment would not deem ‘cruel and unusual’, namely one that makes death rapid, painless and dignified, it’s still going to be fraught with difficulties to argue it is humane.

Let’s begin with firing squad: This is the process of typically strapping a prisoner across the head and wait with leather straps, pulling a hood over his head and lining them up against a wall and pinning a circular white target cloth around the person heart.

Then, from a distance of some 20-25 feet away, marksmen fire multiple rounds to ideally rupture the targets heart or large blood vessel in the hope of ultimately killing them by way of the loss of blood and the brains supply of blood in order to induce unconsciousness.

In short, it’s bleeding a prisoner to death.

Gas Chamber: This is the process of strapping a prisoner to a chair in an airtight chamber, releasing crystals of sodium cyanide into a pail of sulfuric acid in the hope that the prisoner’s normal breathing pattern kills them from the chemical mixture of hydrogen cyanide leading to hypoxia – the cutting-off of oxygen to the brain.

Unfortunately, it seldom happens in the way it’s scripted.

The strapped prisoners have a tendency to hold their breath, denying quick unconsciousness and instead lengthening the process long for as possible to the point of bursting when their skin begins to turn purple, their eyes-balls begin to protrude and the onset of vomiting and hyperventilation finally leads to them succumbing to the effects of the gas.

It’s a dirty and violent death.

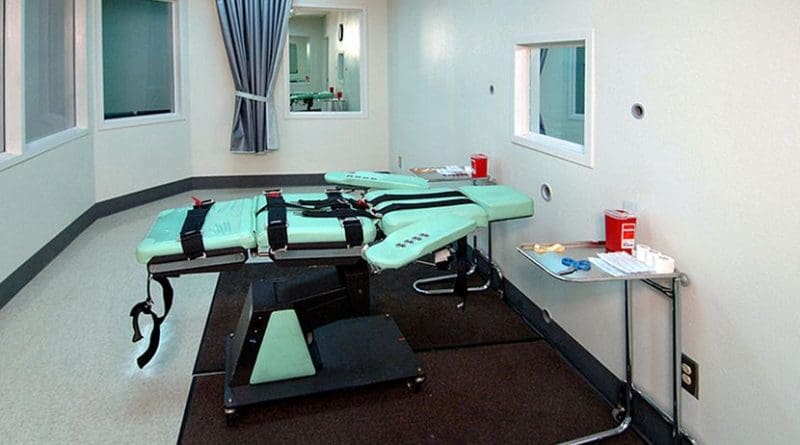

Lethal Injection: This is the process of injecting a gurney-strapped prisoner with a three-drug cocktail of barbiturate, paralytic and toxic agents to induce unconsciousness, muscle paralysis and respiratory arrest before finally stopping the heart.

If you’re reading the manual for it on paper, it seems like its unquestionably the most clean and merciful of all methods.

Not necessarily.

There remains no medical or scientific evidence that proves the practice is free from any unrecognized pain and suffering, it is not a medical procedure that’s undergone scrutiny or peer review to determine it works the way it’s designed to – essentially rendering the person to unconsciousness and paralysis and in turn the inability to breathe.

In all the cases above, we can see nothing can be scientifically proven to always lead to a humane, painless and instant death.

At the same time, is it not wise to argue that the infliction of punishment is all the same since the net result is to cause death in order to uphold the rule of law?

Perhaps those who make a habit of condemning the practices of others on the grounds that their methods of capital punishment pay disregard to western notions of what’s ‘cruel and unusual’ should make a conscious effort to think again.

Mercy might well be above justice, but in being culturally aware of others perhaps what certain societies deem is meant for a prisoner — might just be best for them.

*Mohammad I. Aslam is a Ph.D candidate in Political Science at the Institute of Middle Eastern Studies, King’s College, University of London.

**This article is dedicated to Eunjong Lee, Yonsei University (South Korea)