The EU’s Geopolitical Crossroads In Middle East – Analysis

By FRIDE

By Richard Youngs*

The European Union’s (EU) policies in the Middle East have been implicitly, not overtly geopolitical. The conventional view is that the EU cannot do and resolutely recoils from geopolitics. This is over-stated. EU policies do not fit the mould of classical geopolitics, but they do reflect a distinctive way of thinking about strategic interests. In 2011, the Arab spring’s flush of enthusiasm appeared to give these approaches a persuasive resonance. Today, however, the Middle East’s geopolitical contours more mercilessly expose their shortcomings. The EU consequently finds itself at a crossroads in its Middle Eastern policy. Some suggest that the EU should now move from an implicit to an explicit focus on geopolitical interests.

However, the EU should not attempt to become a standard geopolitical actor. It is not set up to be one. The EU-level of overall European policies can make a contribution to addressing the Middle East’s emerging geopolitics in more subtle ways. In particular, the EU’s relationship with its member state policies will be of vital importance in defining a more effective European strategic approach towards the Middle East and North Africa (MENA).

INCLUSION AS GEOPOLITICS

The European Union – understood here in its narrowest sense as the EU institutions – is not the same kind of actor as other powers. This makes its relationship with geopolitics difficult to define. The EU has competences that are relevant to geopolitical interests. But it does not have the ability to act geopolitically in complete separation from member state governments – and it is the latter that have direct democratic responsibility to their citizens for providing security.

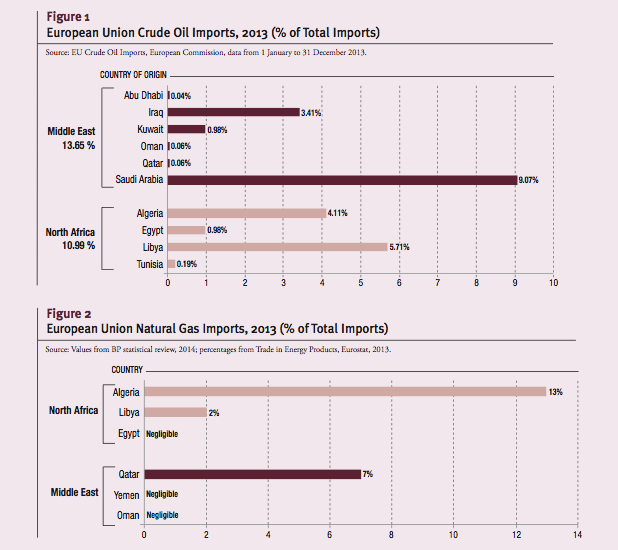

The overall EU geopolitical interest in the MENA region is well known, not least since the proximity of the region exposes the EU to Middle Eastern instability. Many documents, such as the 2003 European Security Strategy, have reiterated the EU’s interest in stable and well-governed states in the Middle East, regional security cooperation and non-proliferation of nuclear weapons. In addition, the presence of migrant communities in Europe means that MENA challenges resonate in more intense ways than in some other external actors, like the United States (US). For example, counter- terrorism and counter-radicalisation are both domestic and foreign policy priorities. The EU also depends on the region for a significant share of its energy needs (shown in Figures 1 and 2).

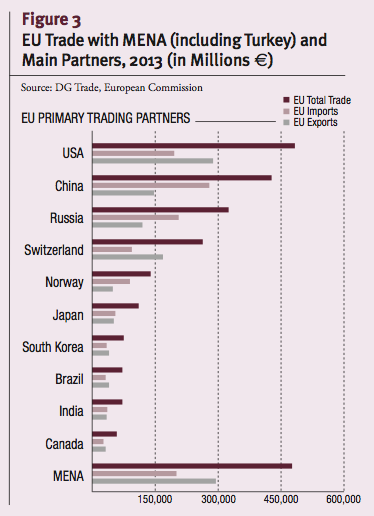

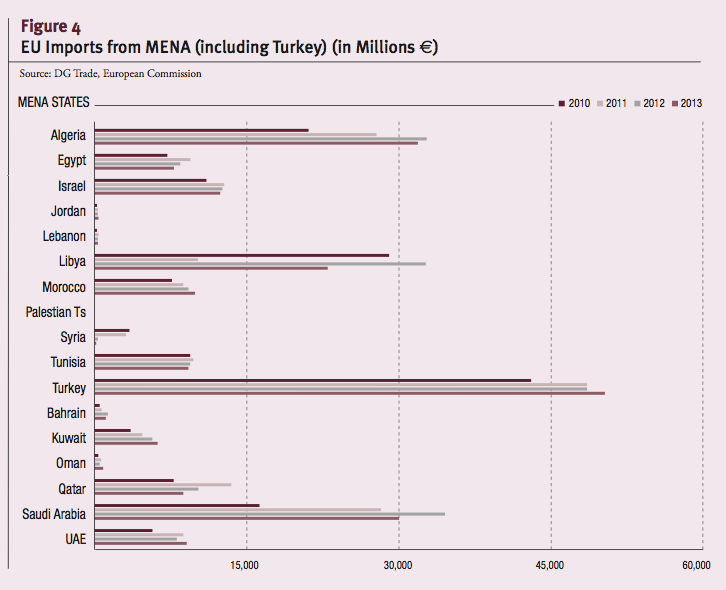

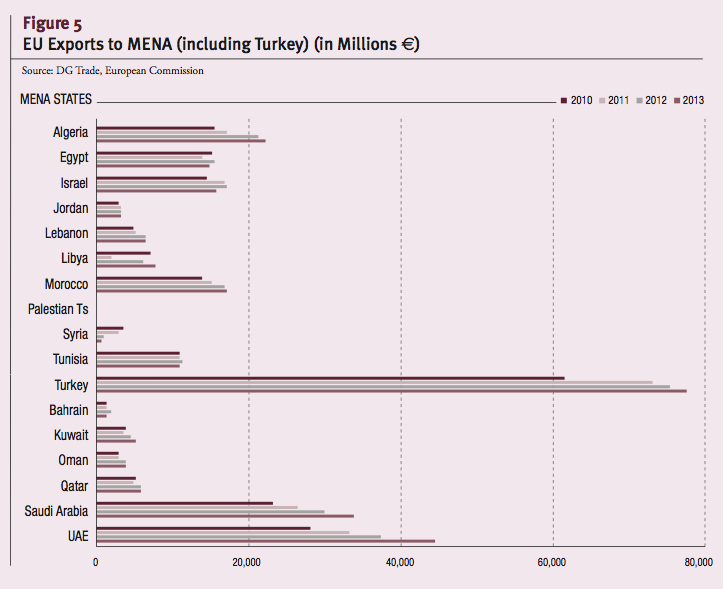

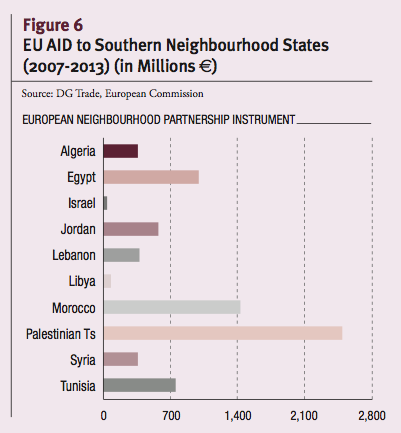

The graphs show that EU commercial ties with the region are growing, albeit well below their potential (Figures 3, 4 and 5). Moreover, the EU spends nearly a fifth of its external aid in the southern Mediterranean (Figure 6). All this makes the MENA region hugely important for the EU.

The EU has policy instruments that exist in addition to those deployed by member states. In certain circumstances, these serve to leverage the combined weight and influence of the Union’s member states. At the same time, the EU institutions – primarily the European External Action Service (EEAS) and different Directorate Generals in the European Commission – have an approach to Middle Eastern challenges that is different from many member state policies. This approach is ‘inclusion as geopolitics’.

Many analysts have unpacked how the EU sets itself up as a kind of benign, post-modern empire, that exerts influence over neighbouring states by incorporating them into its own governance system. This is geopolitics on the basis of voluntary inclusion rather than imposed coercion, of shared power and partnership rather than subjugation and hard-power tutelage. It is an approach that draws much from EU policies in Eastern and Central Europe in the 1990s – applying a similar logic to a very different regional context.

The EU’s potential to exert influence in the Middle East appeared to rise in the wake of the 2011 Arab spring, which inspired widespread hopes for democratic reform throughout the MENA region.

The aim of supporting incipient political change seemed to play to EU strengths, and the Union upgraded its reform instruments. The EU offered some MENA states fuller economic integration into the EU’s vast single market; an additional €1 billion of financial resources to accompany economic, political and social modernisation; and more generous access to labour markets. All these offers to the Middle Eastern participants in the EU’s European Neighbourhood Policy (ENP – the Union’s main policy framework for relations with its immediate neighbours to its south and east) were conditioned on a willingness to implement economic and political reform.

In addition, in contrast to some national governments, EU officials engaged directly with Islamists – not least because they saw the latter as future power- holders, in particular the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt – and mediated between hostile political camps. These were all dimensions of policy where EU instruments provided an added value over and above member states’ national foreign policies. And in 2011 these instruments seemed to be pulling in the same direction as – and amplifying – member states’ geo-strategic intentions.

There are a number of examples of the (sometimes modest) positive impact of the EU’s approach. The EU has been a factor in pushing some improvements to economic governance standards in countries like Morocco, such as competition law and transparency requirements. It has helped solidify certain state structures in Jordan and the Occupied Palestinian Territories, especially planning ministries. It has helped bring about some convergence in energy regulations north and south of the Mediterranean, a geopolitical contribution to what have been relatively untroubled energy security relations. The EU has also encouraged mutually hostile actors into more dialogue than would otherwise have been the case – for example in Yemen, Tunisia and Egypt.

The MENA region’s slide into more visceral conflict and uncertainty is not the EU’s fault. But neither the EU nor the US has been able to reverse this trend. The EU’s policy instruments of inclusion have not sufficed to prevent states descending into brutal violent conflict and exporting instability across borders, and there are many examples of the limited impact of the EU’s approach.

For instance, ENP trade and aid instruments were used as the main means of engaging with Syria’s Assad regime. After Colonel Gaddafi’s ousting in 2011, the EU deployed many initiatives on the ground in Libya, and offered the new government inclusion into the Euro-Mediterranean Partnership (EMP) and ENP frameworks with conditions based on incentives (these incentives were labelled by the then EU foreign policy chief as the ‘three Ms’ – money, markets and mobility). An EU neighbourhood action plan was offered to Algeria, and a free trade accord to Egypt, and the Union poured over €50 million into shoring up Yemen’s fragile, mediated transition. In all these cases, regimes have either rebuffed EU cooperation or they have accepted the EU’s money and then have pushed back against its associated norms of positive- sum, cooperative security.

Today, it is clear that the EU’s indirect, geopolitics-as-inclusion of the last decade failed to deal with some key emerging dangers. While it spurred dialogue on formal commitments to reform, it did not dissect or target the vested interests that have then scuppered economic and political modernisation. While it rightly pursued diplomatic engagement with ‘difficult’ regimes and some opposition groups, it did not have the means to cash in any leverage when events took ugly or problematic turns – especially in Syria, Egypt and Lebanon. And the EU engaged in little action that aimed to forestall the competitive power politics that now dominates in the Middle East.

ADJUSTING TO A NEW ERA?

EU decision-makers face a geopolitical crossroads in the Middle East. It is self-evident that the MENA region has entered a turbulent and unstable period. The focus has shifted from hopes for political reform to conflict management. Sectarian divisions, radical identities and power rivalries have all become more significant drivers of change in the region.

There is broad consensus within EU institutions

that this new reality warrants fundamental changes to the EU’s strategy in the region. As the EEAS and the European Commission embark on a year-long review of the ENP, EU diplomats say the aim must be to make policy in the neighbourhood more like ‘normal’ foreign policy. The EU must think and talk more explicitly in terms of protecting tangible interests. EU policy can no longer be based on the assumption that neighbouring states will smoothly align themselves with and into an EU sphere of governance. Speaking at the March 4th launch of an ideas paper on the EU’s strategy towards its neighbourhood, the EU foreign policy chief, Federica Mogherini, said that the Union ‘needs to move from an approach very much based on the evaluation of progress to a more political approach’.

As security problems bring national governments’ diplomacy centre-stage, the role of EU instruments is less clear. The classic geopolitical concepts of ‘balancing’ and ‘band-wagoning’, ‘containment’ and ‘securitisation’ have quickly moved into the foreground of Brussels debates – the kind of concepts long alien to EU institutions. The focus is on traditional forms of security alliances more than milieu-shaping regional frameworks like the Euro- Mediterranean Partnership.

So, what role can the EU play in this new context? It would certainly be naive for the EU to continue as if nothing new were afoot in the MENA region. But as they review their policy instruments, EU officials should take care not to shift too far in their conception of geopolitical imperatives or be too tempted by the siren call of purely realpolitik diplomacy.

The EU certainly needs a strategy that is more geopolitically sensitive to changes in the Middle East, and policies that are not quite so instinctively led by technocratic matters related to the EU’s own acquis (rules and standards). But care is needed: today’s wall-to-wall advocacy of a more ‘geopolitical approach’ could easily open the door to policies that harm rather than advance European interests.

The common line of reasoning now is that the EU must accept regimes as they are rather than trying to remake them in its own image – due to both its strategic interests and its diminished influence. However, a policy less oriented towards expanding the sphere of ‘euro-governance’ should not mean turning away from the underlying drivers of instability. Far from being blind to geopolitical realism, the EU has already shifted towards securitising its cooperation. To illustrate: in the case of Jordan, the EU has diluted conditions for access to its funding, lowered the priority of supporting political and economic reforms, and redirected funds towards stabilising the country’s borders and dealing with its influx of Syrian and Iraqi refugees. This shift in priorities is entirely understandable; yet, reform imperatives should not be unduly neglected.

The adoption of a more geopolitical policy should not serve as a (in reality, domestically-driven) pretext for arguing that opening European markets or offering freer movement to Arab workers is no longer necessary. Nor should it become shorthand for a policy of keeping the region at a distance instead of working to deepen inclusive cooperation. And it should not point the EU towards using its funds to prop up regimes guilty of atrocious rights abuses. This is a risk now with the military regime in Egypt, as the EU moves towards agreeing a new aid programme. Moves in the direction of exclusionary containment are unlikely to preserve the EU’s long-term strategic interests.

Another argument now frequently made is that the EU should drop its ambitions for building regional cooperation (both within the Middle East and between the EU and MENA region). These ambitions certainly need reframing. Many Middle Eastern regimes are today less interested in regional cooperation than they were a decade ago. But the EU would be ill-advised to give up entirely on encouraging regional cooperation. Again, it would not make for good geopolitics to swap these efforts for a focus only on individual, favoured allies. With many medium sized powers competing for influence, and no clear hegemon in the region, efforts to build regional norms and rules are more, not less, necessary. The threat from Islamic State (IS) is already pushing Iran, Sunni regimes and even Israel to explore (or at least consider) possible coordination.

One positive effect of the crisis in Iraq and Syria is that most European policy-makers do now realise the need for a broader Middle East strategy – that also involves adjacent regions such as the Sahel. It is woeful that this still does not exist, fully four years after the initial Arab revolts began to shift alliances across the region. The EU needs to adapt to the region, rather than seeking to adapt the region to its own prisms.

WITH OR AGAINST MEMBER STATES?

A crucial question for European strategy in the MENA region is the complex relationship between collective EU strategy and member states’ national foreign policies. Are EU instruments a layer of policy that dovetails with and gives added weight to national governments’ strategies in the Middle East? Or do they function as an attempted corrective of the latter, left to function with some autonomy but in practice seriously countermanded by member states’ very different approach to geopolitics?

The answer is: a bit of both. In their responses to the Arab spring, EU and member states’ policies have evolved sometimes in harmony and sometimes in tension with each other. For example, there has been harmony on supporting consensual and inclusive types of reform, but tension on geopolitical engagement in the Gulf. European foreign policy in the Middle East has been neither ‘re-nationalised’ nor ‘Europeanised’; rather, national diplomacy and EU initiatives have developed simultaneously and in parallel.

Part of the European response to the Arab spring was attempting to make real the long-held aim of a cooperative Euro-Mediterranean security community. A number of EU-Mediterranean forums that were relatively dormant, or at least lacklustre, in the years preceding 2011 were (at least for a while) injected with a new lease of life. To some extent these worked to leverage the combined weight of member states’ presence in the Middle East, and acted as a geopolitical multiplier to national diplomacy and policy instruments.

But another part of the response was member state activism aimed at controlling the geopolitical impact of political change. In some parts of the Middle East, the Arab spring encouraged European governments to give greater priority to bilateral, national foreign policy action. The most notable example of this was in the Gulf – where the three bigger member states (France, Germany and the UK) were concerned that revolts could put their security interests at risk (alongside competing for commercial contracts).

A lack of coherence between national and EU policies is not new (and does not only apply to the MENA region). But in the emerging Middle Eastern geopolitical (dis)order, it is even more acutely necessary. This is not about boosting EU instruments to the detriment of national foreign policy efforts. Rather, the premium is on more effective harnessing of the two levels to mutual advantage.

The geopolitical interest and role of the EU must be to coordinate member states more effectively. In a sense, a lot of what it means for the EU to be ‘geopolitical’ lies precisely in the management of this linkage. Active member states insist that their new security engagement – bases in the Gulf, arms sales, training the Jordanian or Algerian security forces – opens the way for engagement on more structural security reforms. The EU should orientate its initiatives to play this security sector reform role – and demonstrate that member states are not disingenuous when they make such claims.

In addition, many member states are worried about the domestic fall-out of returning violent jihadists, and agree on the need for counter-radicalisation programmes. Here EU programmes could complement national domestic efforts and security relations with MENA governments, by focusing more on the softer, social elements of counter-radicalisation work within the Middle East. As national governments engage more assiduously on security issues, the EU institutions will need to find niche areas to glue overarching European strategies together into a seamless whole.

The EU-level will not constitute a single foreign policy in the Middle East; rather, it will need to fill the gaps left by member states’ more geopolitical engagements in the region. In this way, it can help achieve a sensible balance between short-term interests and long-term values.

CONCLUSION

Endless documents, articles and speeches now call on the EU to be more strategic, more geopolitical and more ‘realist’ in its policies towards the MENA region. But the question remains of what it actually means for the EU to be more realist, geopolitical and strategic. Simply calling for such a shift merely displaces the debate to what these concepts mean for how policies are deployed. Much of what is advocated under a realist label may not turn out to be very stable in its results.

The EU is beginning to sharpen its strategic think- ing on the MENA region. This welcome develop- ment should not divert the EU from trying to tackle the most deep-rooted causes of today’s geopolitical conundrums. Taking geopolitics seriously means thinking what strategies are necessary to oxygenate EU efforts to foster structural reforms – it should not mean suffocating such approaches. The times indeed warrant a more hard-headed approach to security. But a wholesale switch from geopolitics-as-inclusion to geopolitics-as-exclusion is not the answer.

About the author:

*Richard Youngs is senior associate on the Democracy and Rule of Law Program based at Carnegie Europe.

Source:

This article was published by FRIDE as Policy Brief 197 (PDF)

This Policy Brief belongs to the project ‘Transitions and Geopolitics in the Arab World: links and implications for international actors’, led by FRIDE and HIVOS. We acknowledge the generous support of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Norway. For further information on this project, please contact: Kawa Hassan, Hivos (k.hassan@ hivos.nl) or Kristina Kausch, FRIDE (kkausch@ fride.org).