Syria: The Dangerous Trap Of Sectarianism – Analysis

By Syria Comment - Joshua Landis

By Nikilaos van Dam, former Ambassador of the Netherlands to Iraq, Egypt, Turkey, Germany and Indonesia

The fact that the issue of sectarianism has, thus far, not figured prominently in discussions on recent violent developments in Syria does not mean that it is not an important undercurrent which could fundamentally undermine the possibility of achieving democracy as demanded by Syrian opposition groups. Syrians are very much aware of it but tend, generally, to avoid talking about sectarianism openly, because it can have such a destructive effect. The early 1980s are an example of this, when the Syrian Muslim Brotherhood provoked the minoritarian Alawi-dominated Ba’th regime into a bloody sectarian confrontation by assassinating various prominent, and less-prominent, Alawi people, not necessarily because they were Ba’thists but because they were Alawis. The climax came with the Muslim Brotherhood revolt in Hama in 1982 which was bloodily suppressed by predominantly Alawi troops, taking the lives of some 10-25.000 inhabitants of the mainly Sunni population there. Nobody would wish to see a repetition of such bloody events, which have left deep social scars. For almost 30 years since the ‘Hama slaughter’, the situation in Syria has been relatively quiet on the sectarian front. This does not mean, however, that the issue of sectarianism could not become acute again, particularly since the Ba’th regime is presently under threat, while its main power institutions, such as the army and security services, are still clearly dominated by a hard core of Alawis who continue to constitute the backbone of the regime.

Whereas the common sectarian, regional and tribal backgrounds of the main Ba’thist rulers have been key to the durability and strength of the regime, their Alawi sectarian background is also inherently one of its main weaknesses. The ‘Alawi factor’ seems to be hindering a peaceful transformation from Syrian dictatorship towards a more widely representative regime. The present Syrian demonstators’ main demands are simply to get more political freedoms and to make an end to the corrupt one party dictatorial system. The sectarianism issue is generally avoided by them. After all, the last thing the opposition seems to want is another sectarian war or confrontation which would not only lead to more violence and suppression, but would also not result in meeting any of their demands. The opposition instead prefers to portray the Syrian people as one and the same, irrespective of them being Arab, Kurd, Sunni, Alawi, Christian, Druze, Isma’ili, or whatever. They want justice, dignity and freedom. Their demands have, thus far, generally been rather modest, democratically oriented and peaceful.

It is good to take into consideration that there is no clear sectarian dichotomy in Syrian society, dividing the country into Alawis and non-Alawis. Syria has never been ruled by ‘the Alawi community’ as such. It is only natural that there are also numerous Alawi opponents to the regime. Many Alawis have themselves been suffering from Alawi-dominated Ba‘thist dictatorship, often just as much as, or occasionally even more than, non-Alawis. This dictatorship rules over all Syrian regions, sectors and population groups, including those with an Alawi majority. Many Alawis are just as eager for political change in Syria, as other Syrians. Syrian youths from all social and ethnic segments are prepared to take great risks to help achieving it. They and others also, however, tend to be carried away by the so-called ‘successes’ of demonstrators elsewhere in the Arab world, particularly in Tunisia, Egypt, Yemen and Libya. But when it comes to the dangerous issue of sectarianism, Syria is a special case.

It appears difficult to imagine a scenario in which the present narrowly based, totalitarian regime, dominated by members of the Alawi minority, who traditionally have been discriminated against by the Sunni majority, and who themselves have during the past decades severely repressed part of that same Sunni population, can now be peacefully transformed into a more widely based democracy, involving a greater part of the Sunni majority. A transformation from Alawi-dominated dictatorship to democracy in Syria should certainly not be taken for granted as a self-evident development, because it would imply that present repressive institutions should be dismantled, and that the regime would have to give up its privileged positions. As the traditional Sunni population in general has apparently not given up its prejudice and traditional negative attitude towards Alawi religion and Alawis in general – it might even be argued that Sunni grudges against Alawis have only increased as a result of Alawi-dominated dictatorship – it seems only logical to expect that the presently privileged Alawi rulers cannot count on much understanding from a more democratic (or less dictatorial, or perhaps even more repressive) regime which would for instance be dominated by members of the Sunni majority. A nascent democratic regime might in the end – due partly to lack of any long-term democratic tradition in Syria – turn into a Sunni dominated or other kind of dictatorship, members of which might wish to take revenge against their former Alawi rulers and oppressors. Many Alawis, including some of the regime’s initial opponents, might feel forced to cluster together for self-preservation if they would be given the impression, whether justified or not, of being threatened by a Sunni majority.

Perhaps there might be a way out through a kind of national dialogue with the aim of reconciliation. But such a reconciliation is only possible if enough trust can be created among the various parties. Why would key figures in the Syrian regime voluntarily give up their positions if they can hardly expect anything other than being court-martialed and imprisoned afterwords?

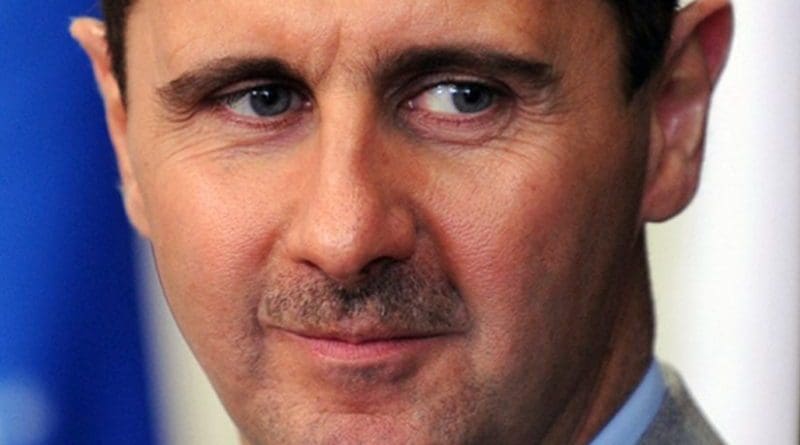

A good beginning could be made by the Syrian regime through essential reform measures by way of an adequate response to the reasonable demands of the democratically and peacefully oriented opposition. Having a totalitarian regime, president Bashar al-Asad should at least be able to control all his security institutions, as well as armed irregular Alawi gangs like the Shabbihah, to guide Syria out of this crisis in a peaceful manner. Falling in the dangerous trap of sectarianism is in nobody’s interest, least of all of the Alawi community, which wishes a better future for Syria, like anyone else in the country.

—–

Nikolaos van Dam is former Ambassador of the Netherlands to Iraq, Egypt, Turkey, Germany and Indonesia and the author of The Struggle for Power in Syria (its 4th updated edition is to be published shortly).