Neo-Liberal Development Discourse A Hurdle In ‘Development’: Study Of Naxalites Issue – Analysis

By Umm-e-Habiba

I. Introduction

In the liberal economic discourse, it is generally assumed that ‘development’ leads to prosperity and social peace. The hypothesis that economic growth leads to an increase in opportunities and a reduction in inequalities, both social and economic, is predominantly thought to be ‘universal.’ Economic dissatisfaction, it is believed, can persuade people to express an ‘anti-social behaviour’. And, it is especially likely among those who even happened to have made considerable efforts to improve their position by “legitimate” means, but found themselves incapable of doing so within the given frameworks of the otherwise ‘neo-liberal’ system.

This notion regarding development is also utilized politically, premising that restive movements can be controlled by introducing economic developmental projects in such areas. Hence, economic development is considered to be a potential political tool to counter social unrest. Like many other states, the Indian state also has been led by such assumptions, and these assumptions have some sort of empirical/historical base if we recall the case of Khalsa Movement in the Indian Punjab, and the way it was de-escalated by large scale developments, especially in agriculture sector.

However, the case of Naxalites’ Movement poses a challenge to this assumption that development per se can be a successful means of curbing social unrest and/or socio-political movements. Their movement is considered to be ‘anti-development’ in the sense that any such move of development, they believe, fostered by private capitalists/industrialists would dispossess and dislocate them of and from their land—hence, disadvantageous to them. This stance poses a critical question not only to the notion of “development” but also problematizes neo-liberal regime’s ability to integrate disparate elements into the polity.

Notwithstanding the economic underpinnings of the Naxalite movement, it is no longer only economic or agrarian in nature. With the passage of time, the ‘political’ aspect has acquired as much importance, if not overwhelmed, the ‘economic’ aspect. It is for this reason that the discourse of development, as propagated by the state, has not been able to make any meaningful headway into the Naxalites’ ideological disposition.

The meaning of this movement has changed over the period of time, evolving from a struggle to avoid land dispossession to challenging the fundamentals of the post-colonial state—hence, the propagation of an anti-imperialist and anti-elitist counter-discourse. By resorting to militant tactics, the Naxalites have challenged the State’s ‘legitimate monopoly’ over the use of force. Notwithstanding these developments, the Naxalite problem continues to be mostly looked at as essentially an economic problem—something that can be ‘solved’ by allowing for development; while its political dimension remains largely ignored or is appreciated only as a sub-theme.

The focus of this article will, therefore, be both economic and political dimension of the Naxalite movement, and its conceptualization as a counter-hegemonic movement, challenging the hegemony of the state and establishing a counter-structure to the state’s structure. We will argue that the Naxalites have not only established a ‘state’ within the Indian state, but have also developed enough machinery to run this ‘state’, as also a politico-economic system.

However, their territorial stretch remains limited to their areas, primarily because they do not enjoy any ‘external’ political support; for, neither the international scenario any longer supports such ‘radical’ ideologies as Maoism, nor have they acquired enough resources to re-structure the Indian state on Maoist lines.

These limitations, however, do not imply that they do not envision a re-structured political and power structure—hence, the crucial necessity of understanding the politics of the Naxalites. On the other hand, it would be an oversimplification to deny the economic undercurrents of the Naxalite problem.

As a matter of fact, neither is the economic dimension irrelevant, nor can the movement’s political dimension be understood without first understanding the economic aspect. It would not be wrong to contend that the reason for why the political aspect is gaining more significance is the “internal imperialism”, as Naxalites like to call it, being practiced by the Indian state and it successive governments in the shape of development projects.

Development projects, as sponsored by the state, tend to deprive the the Adivasis of their land and forests; therefore, the core problem is the state and successive governments which direct these policies and allow corporate interests to snatch their land. The political and economic are thus two integrated and inseparable dimensions, requiring to be studied as such in order for fully comprehending the movement’s dynamics; its internal system; and its immediate and long-term objectives.

II. The State Behaviour

The Adivasis have a history of resistance against oppressive systems. Even the colonial period witnessed resistance from this ethnic group. Although the movement in its present shape has transformed a lot, the struggle against prevalent system was neither an altogether a new phenomenon for them nor for the post-independence Indian state.

However, the attitude of the Naxalbaris i.e. the attempt to pay the state and its representatives ‘in kind’ has not emerged all of a sudden. The cause of such aggressive response to the state has its roots linked with the state’s decades long approach vis-à-vis the adivasis. During the initial phase of independent India the struggle or resistance was comparatively less intense probably because Adivasis were expecting something relatively positive from the new setup.

Also, the governmental reports of 1950s endorsed this fact that the then Indian State had at least tried to understand its tribal community. For instance, the committee formed by the Home Ministry in mid 1950s to enquire into the performance of government schemes in tribal areas found that the officials of such schemes “were lacking in any intimate knowledge of their people [and] had very little idea of general policies for tribal development. After studying 20 blocks spread across the country, the committee concluded that of the many tribal problems the greatest of all is poverty”1

However, the mistake on the part of Indian State is that it understood the problem only in economic terms and ignored other dynamics of the issue, therefore, government’s response whenever came was always in economic terms.Keeping in view the development’s economic outcomes,government tried to make certain strategies but one after the other they failed.

They failed because the purpose was not “development only” it was targeted development in a sense that government conceived that by giving certain economic benefits it can entice the masses. Thus, the effort was destined to separate the militants from peasants which was again a divide and rule policy.2 For instance, land distribution or reforms must have had certain positive impacts but the state’s policy of divide and rule practiced in the shape of giving lands to local peasants on the one hand, and encouraging other or local resistance groups against the Naxalites on the other hand, directly resulted in pushing the movement into the political sphere of activity.

For example, according to a report presented to the planning commission of India in 2008, the government of India did pursue this divide and rule policy in order for weaning the “angry peasants” away from the “militants.” The report mentions different policies of successive governments which clearly highlight how the problem had been understood and what solutions were recommended as such.

For instance, policy of the first United Front Government in West Bengal in 1967 recommended a policy based upon Mao’s “fish and water theory”, which aimed at separating the fish from water. In other words, the policy recommended the separation of peasantry from militants by giving lands to the otherwise “angry peasants.”3

According to the said report, this strategy worked out well and succeeded in weaning peasantry from the Naxalites. However, this policy failed to succeed in areas other than West Bengal largely because of non-implementation. Similarly, a policy paper of Ministry of Home Affairs of 2006 recommends to “promote local resistance groups against the Naxalites”4 and to “use mass media to highlight the futility of Naxal violence and the loss of life and property caused by it.” But this strategy too failed to bring a meaningful solution to the problem.

As the said report itself mentions that the government’s failure to remove land, food, livelihood insecurities and removal of social and economic oppression directly impeded the effective application of these measures. Besides it, the recommendation to promote local resistance groups also glaringly highlights that the state/government was itself directly involved in precipitating and fomenting mass violence. The State’s self-contradictory approach to the problem is not only self-defeating but also counter-productive in that it plays the role of convincing the peasantry and the militants of the crucial necessity of overthrowing the state.

Implicit in these policy recommendations is the state’s understanding of both peasantry and militants as two different phenomenon. Not only is this understanding deliberately projected by the state but also does not take into account the socio-political realities of the region, especially its history.

As Arundhati Roy argues that the people have a history of resistance against oppression, and that they had been resisting oppression for centuries, when we take the history into account, it becomes clear that the nomenclature i.e., Maoism is very recent. 5 (Underlined portion are my words not her.) She further argues that the tribal people have a history of resistance, which very well predates Mao, against the British, the zamindars and the money landers.

Although these frequent uprisings were crushed and thousands killed consequently, the people were however never conquered. Even after independence, tribal people were at the heart of first uprising that could be described as Maoist, in naxalbari village in West Bengal. “This legacy of rebellion”, she argues, “has left behind a people who have been deliberately isolated and marginalized by the Indian governments.”6

Post-independence political developments established a ‘new’ structure which made the “tribal population squatters on their own land, denied them their traditional rights to forest produce, it criminalized a whole way of life. In exchange for the right to vote, it snatched away their right to livelihood and dignity”7; for, they were periodically forced to leave their lands and forests for the sake of “development and modernization.”

This ‘dispossession for accumulation’ policy of the state has had the effect of making the tribal people more and more anti-state and anti-imperialist. Therefore, over time, their resistance and struggle has acquired a more violent face. It must be mentioned here that the Naxalites’violent measures are a direct repercussion of structural violence in-built in the state’s socio-economic and political system.8

It is perhaps for this reason that their struggle has gradually turned anti-imperialist and anti-state. It is easier to believe that the conflict is between the Naxalites and the government; however, the conflict is not merely a conflict for resources; it has now turned into a struggle for political power.

To quote A. Roy again, the Naxalites, “call elections a sham, parliament a pigsty and have openly declared their intention to overthrow the Indian state.”9In this behalf, Charu Mazumdar’s idea of the revolutionary youth’s transformation into “new men”10 is not merely an idea of the transformation of human beings but also an idea of the transformation of the “old” state into a “new” state.This inter-relation between the two ideals becomes clear from the following declaration, made in 1972, of West Bengal-Bihar border committee of the movement, which declared that “the struggle of ours is not only [for] a seizure of power. Comrade Charu Mazumdar has said that we must become new men. This is a struggle for the birth of new men.”11

And, as a number of studies have brought to light, the Naxalite movement of the 1970s in West Bengal aimed at completely overhauling the existing political and ideological structures of Bengali ‘bhadrolok’ society.12

Transformation of power structure and the knowledge produced by these structures were (and still are) both considered to be critical impediments in the way of achieving freedom—hence, the crucial necessity of acquiring a revolutionary personality to achieve revolutionary goals i.e., a radically transformed structure of the state.

III. The Alternative ‘they’ Demand:

Moreover, the Naxali ideal of transformation of power structure is based upon practical philosophy. The best example of which is theirJantanum Sarkar (JS)–a state parallel to existent system, has taken several initiativesto improve the living standard of its people. The JS has established tax, health, education and governing systems all operating of course with the involvement of masses, thus enabling the masses to be a productive part of what they consider to be “development” in real terms. 13

The Health and Education System

For instance, their health department, although different from the ‘modern standards’, has the capacity to treat patients of malaria, cholera and elephantiasis with the help of ‘local doctors’-trained members of the Revo lutionary People’s Committee (RPC)14. They were not only taught symptoms and cure of the diseases but also made familiar with the use of medicine. Similarly, an education system comprised of mobile classes, despite the political situation of any particular areais functional under JS. Teachers, mostly three in one camp, teach the modern subjects such as science, mathematics and history etc. to a class of 25 to 30 students. Children are being taught by teaching aids such as globes and CDs.15

The Governing and Tax System

“The RPCs elections are held every three years. The elected RPCs select members for the ARPCs…. on an average, up to 15 RPCs constitute an ARPC. Each RPC holds a general body meeting where accounts are shared and reviewed. Similarly, an ARPC’s accounts are discussed in extended meetings of all the RPCs that come under it. In both the RPCs and ARPCs, members have the right to recall any office bearer if he or she is found wanting in any respect.”16

Aforementioned examples of a functional system along with its system of deliverance to the masses endorse the fact that they are not only able to challenge the system but equally good in providing an alternative, howsoever fragile and small in scale it may be. Contrary to displacement and dispossession caused by the so-called “neo-liberal” mode of “development”, they have introduced an indigenous sort of development, wherein displacement and dispossession appear to be nonexistent.

As compared to the ‘sympathy’ of state which it expresses every now and then by introducing some new mega project the Naxalites pursued a policy that enabled people, with“the most oppressed taking the lead, to struggle and realize their aspirations by participating in making their own lives.”17In the given context, the difference between these two approaches towards development, one of the Indian State and the other of the JS, has raised the question of which one is the legitimate one, at least for the Adivasis? The question of legitimacy can be properly understood by further highlighting the way the Indian State has been and still is politically treating them.

As a matter of fact, it is not only their system of deliverance which matters for the masses, but also a series of injustice committed by the Indian State. Physical violence, economic deprivation and suppression under the cover of ‘development’ and all such factors have compelled the Naxalites to demand and struggle for an alternative state/system for their survival.

IV. Crush the ‘Rebels’ by Every Possible Mean

There is a list of state atrocities against the Naxalites which is considered as the ‘normal’ state behavior towards them; probably because it is the price they have to pay for having an ideology ‘unsuitable’ to the interests of neoliberal state and its representatives. For instance, the ‘encounter deaths’ of the Naxalites is a widely known and old tactic of the state which has been in practice since 1960s.

The Organization for the Protection of Democratic Rights listed about 275 cases of so-called encounter in 1977.18 Previously, the government at least used to deny such ruthless killings of Naxalites in ‘encounters’ if, in case, reported by any independent body.19 However, gradually, the government does not even bother to respond to any such report.

But by that time (mid 1970s) when the ruthless methods of wiping out Naxals, which were used in West Bengal and Andra Pradesh in the early 1970s, were applied in Bihar, the government did not even bother to hide. Fifteen men, branded as Naxalites, were shot dead or burnt to death, despite the fact that three of them had surrendered to the police before they were shot down.20

Later, the introduction of term “terrorism” and connotation related to it further facilitated the government to tag the struggle of the adivasis against the ruthless face of ‘development’ as an act of terrorism which simply implies crushing them without any second thought.

POTA (Prevention Of Terrorism Acts 2002) is one such example, which defines ‘terrorist activities’ as “any act that threatens the “unity, integrity, security or sovereignty of India or to strike terror in the people or any section of the people….or disruption of any supplies or services essential to the life of the community”, etc.”21In more than 19 months of its existence POTA has established itself as a piece of legislation that is meant to terrorize precisely those sections of the population that are vulnerable and are victims of gross injustices.

Not surprisingly, landless or land-poor dalits and the adivasis, who are accused of being terrorists, are one of those groups which are being charged under POTA, thus suffering at the hands of oppressive Indian Regime.22Whereas, as we shall see in the following lines, with the example of Salwa Judum Campaign in Chhattisgarh, neither the government nor the security forces could be charged guilty of any of the offences listed inthe POTA. None of their acts threaten unity, integrity, security whether they loot, rape or kill masses.

In 2005, when the Chhattisgarh government started the Salwa Judum, (The Collective Peace Campaign) in Dantewada, they evacuated the villages, shifted the Adivasis into shelter camps. The adivasis, who resisted leaving their homes, were dealt by the police force who along with rascals (goondas) pounced on the villagers and force them into camps. Those who tried to run away from those camps the police had a ready solution for them i.e. to shoot, keep in detention without any judicial order or to rape them. Even then at certain point 50,000 adivasis managed to run to away from the so-called shelter camps, but this simple act of moving back to home made them terrorists in the eyes of Raman Singh-the then CM of Chhattisgarh.23

Whereas, when the Indian Supreme Court ordered the government (after 3 years in 2008) to rehabilitate and compensate the villagers- the homeless victims of Salwa Judum, neither of those villages were rehabilitated nor a single Adivasi was compensated.24When the adivasis, with the support of some activists, tried to rehabilitate the villages on the basis of self-help once more, the police started attacking the rehabilitated villages and deteriorated the peace. To defend the villages against the SalwaJudum forces, the adivasis started to use lathis, field implements or whatever they had, the then Home Minister Chidambaram declared them as terrorists who want to sabotage and challenge the writ of the state by taking up arms against the government.

In ‘response’ the government went on attacking them with the aim of their ‘welfare’ so that the government could grab their land for industrial projects; thus, ‘fulfill’ its commitment to provide them‘fruits of development’.

V. Conclusion

In the given scenario, despite all systematic difficulties when the adivasis tried to register FIRs against state representatives’ (the police)crimes such as rape, abduction, setting fire to homes, they were denied by the police on the basis that their complaints were‘false’.25“All roads are closed for them. The police beat them.

The political leaders – be they Congress or Bharatiya Janata Party – are with the Salwa Judum. The courts do not give them a hearing. The media does not care”26 and when they resist, the government says it is the biggest internal security threat to Indian state and by giving them (tribals) ‘economic benefits’ we can entice the distracted youth and thus contain their restive movement, by giving them space in mainstream economic activity. By developing political discourses through electronic and print media the state has always tried to manifest the issue as economic one, thus, shun down this reality that there could be any political differences too.

Because of deliberate state policies a large number of the adivasis have lost their homes and lands.The estimates vary – they range from a few million to as many as 20 million. The sociologist Walter Fernandes estimates that about 40 per cent of all those displaced by government projects are of tribal origin.27As per Times of India, the Census 2011 indicates that the adivasis’ share in the general population28 is 9% this implies that a tribal verses a non-tribal ratio to be forced to sacrifice his home and hearth by the claims and demands of ‘development’ is 5:1.

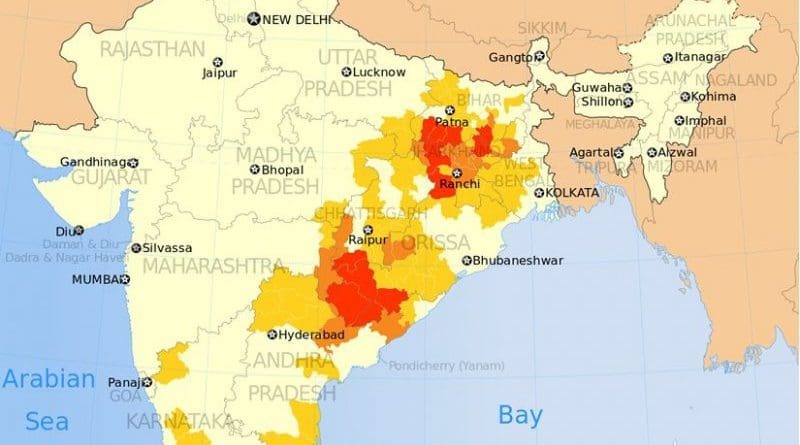

Continuous governmental policies for ‘development’ have exacerbated the situation and the problem has been expanded almost up to 22% of Indian territory.

Moreover, report of the same newspaper states that they (the adivasis) make up 11% of all ‘prisoners’ in the Indian Prisons. This trend is not so because these communities commit more crimes by nature, rather, it arises because they are consciously being kept economically and socially under-privileged, unable to fight costly cases or often even pay for bail, and are even charged with the false cases.

Over the past five decades, the adivasis have often expressed their collective grievances and discontent with the policies and programs of the state. Thus, over the time their protest and disaffection with the system has been emerged in the form of revolutionary armed struggle. They are frustrated with the existing system not only because of its economic but also because of its political structure which is beneficial only to those social groups which are part of status-quo.

Such restive movements which have an ideological base and indigenous participation cannot be curtailed merely by ‘enchanting slogans of development discourse’.

Moreover, to set up an alternative system, wherever they get a chance, shows that the system they want to establish would be a step ahead from mere slogans. Although they realize that the entire state machinery is against them, they are not scared, they believe that to establish people’s power they have to fight, if they get scare, the government will scare them even more.29Instead of forced and alien modes of development they probably want a “self-invented” road to development. However, because of the inbuilt limitations of the neoliberal economic system their ‘difference of opinion’ per se is an ‘offensive move’, for which they are paying a heavy price as they are the‘biggest internal security threat to India’.

Notes:

1. Ramachandra Guha, “The adivasis, Naxalites and Indian Democracy”, Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. 42, No. 32 (Aug. 11-17, 2007), 3307. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4419895Accessed: 18/12/2014.

2. “Development Challenges in Extremist Affected Areas — Report of an Expert Group”, Planning Commission Government of India, New Delhi, 63. http://planningcommission.gov.in/reports/publications/rep_dce.pdfAccessed: 18/12/2014.

3. Ibid.

4. Ibid., p 64

5. Arundhati Roy,“Walking With The Comrades ¼”, Outlook India, March 24, 2010. 03

6. Ibid

7. Ibid

8. Sumanta Banerjee, “Naxalites: Time for Introspection”, Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. 38, No. 44 (Nov. 1-7, 2003), 4635. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4414212 .Accessed: 16/12/2014

9. Arundhati Roy, “Walking With The Comrades ¼”, Outlook India, March 24, 2010. 03

10. RajeshwariDasgupta,“Towards the ‘New Man’: Revolutionary Youth and Rural Agency in the Naxalite Movement”, Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. 41, No. 19 (May 13-19, 2006), 1920, http://www.jstor.org/stable/4418215Accessed: 21/01/2015.

11. Ibid, 1920 and 1926.

12. Ibid. 1920

13. GautamNavlakha ,“Days and Nights in the Maoist Heartland”, 44, http://www.indiaenvironmentportal.org.in/files/Days%20and%20Nights%20in.pdf Accessed: 16/12/2014.

14. An RPC is an elected body which governs three to five villages; 14 to 15 RPCs make up an Area RPC (ARPC); and three to five ARPCs constitute a Division.

15. GautamNavlakha , “Days and Nights in the Maoist Heartland” , 44, http://www.indiaenvironmentportal.org.in/files/Days%20and%20Nights%20in.pdf Accessed: 16/12/2014

16. Ibid

17. Ibid, 41.

18. “Ominous Silence on Killings”, Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. 12, No. 24 (Jun. 11, 1977), 943. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4365676Accessed: 18/12/2014

19. For example, the Amnesty International Report of 1974, on naxalites prisoners and prison conditions or the report of Civil Rights Committee (Tarkunde) For further details see “Ominous Silence on Killings”, Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. 12, No. . (Jun. 11, 1977), 943-944. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4365676Accessed: 18/12/2014

20. Arun Sinha, “Kill Them and Call Them Naxalites”, Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. 10, No. 23 (Jun. 7, 1975), 872. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4537163Accessed: 16/12/2014

21. GautamNavlakha “POTA: Freedom to Terrorise”,Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. 38, No. 29 (Jul. 19-25, 2003), 3039. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4413800Accessed: 21/01/2015

22. Ibid

23. HIMANSHU KUMAR, “Who Is the Problem, the CPI(Maoist) or the Indian State?”, Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. 44, No. 47 (NOVEMBER 21-27, 2009), 8. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25663803 Accessed: 18/12/2014.

24. Ibid

25. Ibid, 9.

26. Ibid

27. Walter Fernandes,Georg Pfeiffer and Deepak Kumar Behera (eds).“DEVELOPMENT INDUCED DISPLACEMENT: IMPACT ON TRIBAL WOMEN”, Contemporary Society: Tribal Studies Volume 6: Tribal Situation in India. New Delhi: Concept Publishing Company, 70-85. http://onlineministries.creighton.edu/CollaborativeMinistry/NESRC/Walter/WOMENDPS.doc ,Accessed 1/2/2015.

28. Subodh Varma,“Muslims, dalits and tribals make up 53% of all prisoners in India”Nov 24,2014. http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/Muslims-dalits-and-tribals-make-up-53-of-all-prisoners-in-India/articleshow/45253329.cms Accessed 1/2/2015.

29. GautamNavlakha ,“Days and Nights in the Maoist Heartland” , 40, http://www.indiaenvironmentportal.org.in/files/Days%20and%20Nights%20in.pdf Accessed: 16/12/2014