Why New US Embassy Isn’t Entirely In Israel – Analysis

By VOA

By Michael Lipin

The new United States embassy for Israel, housed in a U.S. consulate built in Jerusalem in 2010, is located partly on a plot of land that Washington does not officially recognize as Israeli territory.

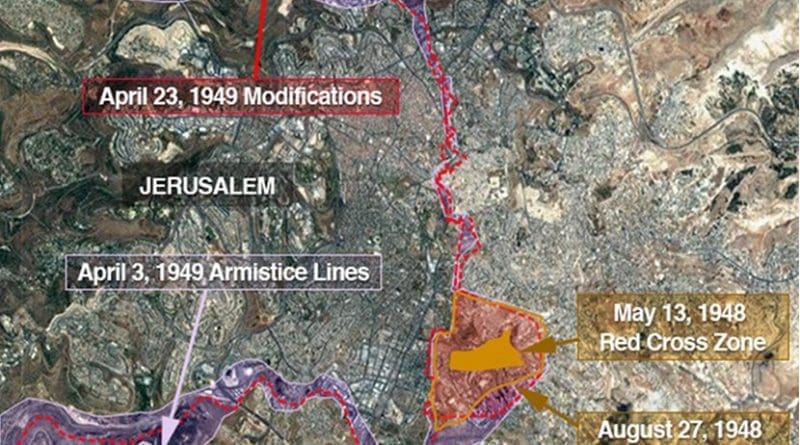

U.S. State Department spokeswoman Heather Nauert has referred to the embassy site as being “partly in West Jerusalem” — the portion of the city recognized by the U.N. as Israeli territory — and “partly in No Man’s Land” between the Israeli-Jordanian armistice lines of April 23, 1949. The western perimeter of that no man’s land, which appears as a five-sided box on Google Maps, runs through the embassy complex.

That land also is what a U.N. official calls “occupied territory”, under 1949’s Fourth Geneva Convention and 1907’s Hague Convention.

The senior U.N. official spoke to VOA on the condition of anonymity because of the sensitivity of the topic.

The Trump administration has said it takes no position on the specific boundaries of Israeli sovereignty in Jerusalem, even while recognizing the city as Israel’s capital.

But, some Mideast scholars say they believe the embassy location means the U.S. actually is taking a position on sovereignty in Jerusalem, which Israel calls its undivided capital.

Palestinians claim East Jerusalem, captured by Israel from Jordan in the 1967 Arab-Israeli war, as the capital of an independent Palestinian state.

Former U.S. ambassador to Israel Daniel Kurtzer told VOA that putting the embassy on the ‘no man’s land’ that Israel annexed to its capital after 1967 is a “de facto” recognition of Israel’s action. Kurtzer, a professor of international affairs at Princeton, served as ambassador from 2001 to 2005.

For Eugene Kontorovich, an international law professor at Northwestern University, the move is even more significant. In a Wall Street Journal op-ed published Sunday, he said the embassy site “demonstrates that the U.S. not only sees Jerusalem as Israel’s capital, but also … recognizes the city as unified.”

The U.S. State Department declined to answer a VOA question about whether the embassy location represents a U.S. recognition of Israeli annexation of the ‘no man’s land.’ It also declined to say whether it shares the U.N. official’s view of the area as Israeli-occupied.

The U.S. embassy in Jerusalem’s Arnona neighborhood is meant to be temporary. U.S. officials have said they are looking for a permanent Jerusalem location that will take years to develop.

The global reaction to the peculiar nature of the temporary embassy site has been muted, even from Israel. It has praised the embassy move but said nothing publicly about the venue’s territorial significance.

Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas’ government has been similarly quiet on the issue, besides one comment made by PLO negotiator Ashraf Khatib to the New York Times. It quoted him in March as saying the no man’s land is “occupied territory” whose permanent status should be resolved in negotiations with Israel.

Last month’s Arab League summit in Saudi Arabia produced a communique saying the leaders “affirm the illegality of the American decision to recognize Jerusalem as the capital of Israel” but mentioning nothing about the embassy site.

Since the U.S. announced the location in a February 23 statement, no U.N. bodies or leaders have said anything about it publicly, either.

Palestinian officials have said little about the embassy location because they are “horrified” by the initial U.S. decision to recognize Jerusalem as Israel’s capital last December, says Wilson Center analyst Aaron David Miller, a former U.S. State Department advisor on Arab-Israeli negotiations. “The issue is not where the embassy is going [in Jerusalem], it is the fact that the embassy is going [to Jerusalem],” he told VOA.

Another reason the embassy location may not be a key issue for Palestinians is that the U.N. official who spoke to VOA described the site as “occupied territory” but not “Occupied Palestinian Territory (OPT)”. The U.N. uses “OPT” to refer to territories that had been under formal Jordanian control until Israel captured them in 1967. Jordan transferred its claims for those territories to the Palestinians in 1988. As for the areas between Israeli-Jordanian armistice lines, like the site of the Jerusalem embassy, the U.N. official said the world body never recognized such areas as under the formal control of any side in the conflict.

Israel’s quietness on the significance of the U.S. embassy site may be related to another historical quirk— Israel’s informal 1949 agreement with Jordan to partition the ‘no-man’s land’ into an Israeli sector in the west, a Jordanian sector in the east and an enclave in the middle for the headquarters of the U.N. Truce Supervision Organization (UNTSO). The partition never was formalized on a legally binding map, but Israel permitted its civilians and even security personnel to operate in its sector from 1949 to 1967 with little interference either from Jordan or UNTSO.

The continuous Israeli use of the western part of the no man’s land makes putting the U.S. embassy there uncontroversial for Israelis from both the right and left of the political spectrum. In interviews with VOA, Israeli military historian Yagil Henkin of the conservative Jerusalem Institute for Strategic Studies said he cannot see “any significance” to the specific area, while Israeli attorney Daniel Seidemann of liberal research group Terrestrial Jerusalem said he feels “intellectually dishonest” calling the site occupied. The Trump administration also has cited “continuous Israeli use” in explaining its choice of embassy locale.

Former U.S. ambassador Dennis Ross, who served as a mediator in Israeli-Palestinian peace talks, told VOA that he sees some logic in the Trump administration’s vague language on the embassy location.

“By opening an embassy on the site, there is an implication that the U.S. administration ultimately feels this will become part of Israel,” said Ross. “But, they have reserved a bit of ambiguity, and international relations often are based on preserving certain kinds of ambiguities.”