Shetland Islands Mull Post-Brexit Independence

By EurActiv

(EurActiv) — Of all the consequences of the Brexit vote, the fate of the Shetland Islands in the North Atlantic and their oil fields and fisheries may not top the list for negotiators in Westminster and Brussels. But it soon might.

But the prospect of a new bid for Scottish independence as Britain leaves the EU is making some residents of these rugged islands think again about whether they would be better off alone.

“It would be wonderful,” Andrea Manson, a Shetland councillor and a leading figure in the Wir Shetland movement for greater autonomy, told AFP.

The movement’s name means “Our Shetland” in the local Scots dialect, a derivation of Middle English which has replaced the islands’ original Germanic language, Norn.

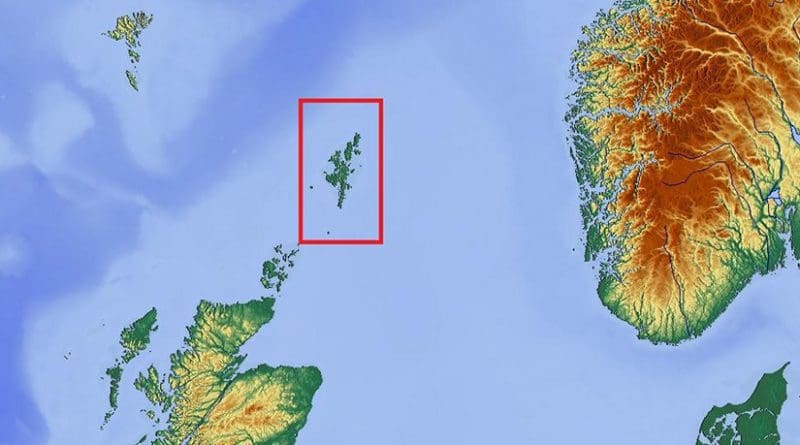

The remote archipelago, already fiercely independent in spirit, is geographically and culturally closer to Scandinavia than to Edinburgh, and politically more aligned with London and Brussels.

In the past 1,300 years, Shetland has been overrun by Scandinavian Vikings, pawned to Scotland as a wedding dowry by Denmark, subsumed into the United Kingdom in 1707, and dragged into the European Economic Community against its will in 1973.

The Shetlands were the only part of Britain, along with the Western Isles of Scotland, that voted against EEC membership in a 1975 referendum.

‘Control of the seabed’

Many Shetlanders are sceptical of Scottish separatism.

In the final tense days of the 2014 independence referendum, local MP Alistair Carmichael, who was minister for Scotland at the time, said the islands could try to remain part of Britain if the rest of Scotland left.

In the end, 55% of Scots voted to stay in Britain. The unionist vote in the Shetlands was 63.7%, one of the highest levels in Scotland.

Now Scottish First Minister Nicola Sturgeon has warned that a second independence referendum is “highly likely” following the Brexit vote and Shetland is once again considering its position.

“We would like control of the seabed around us, the fishing ground around us, and the freedom to get rid of some of the bureaucracy that comes down from the EU, Westminster and the Scottish parliament,” Manson said.

“Our seas are being plundered by foreign boats. We also contribute an enormous amount of money to the national economy through taxes, through the oil revenues, and yet we don’t get back our fair share.”

Scotland has around 60% of the EU’s oil reserves and the second-largest volume of proven natural gas reserves, most of it located around Shetland.

The islands also land more fish than ports in England, Wales and Northern Ireland combined.

“I don’t suppose we would ever be allowed full independence,” Manson said, adding: “In an ideal world we would be a British overseas territory. We would be to Britain what Faroe is to Denmark.”

The Faroe Islands lie about 320 km northwest of Shetland and have autonomous status within the Kingdom of Denmark.

They have an almost identical landmass to Shetland but twice the population, and many Shetlanders envy the archipelago’s independent parliament and vast sovereign waters.

The Faroe Island will hold a referendum in April 2018 on a new constitution that would give the territory the right to self-determination.