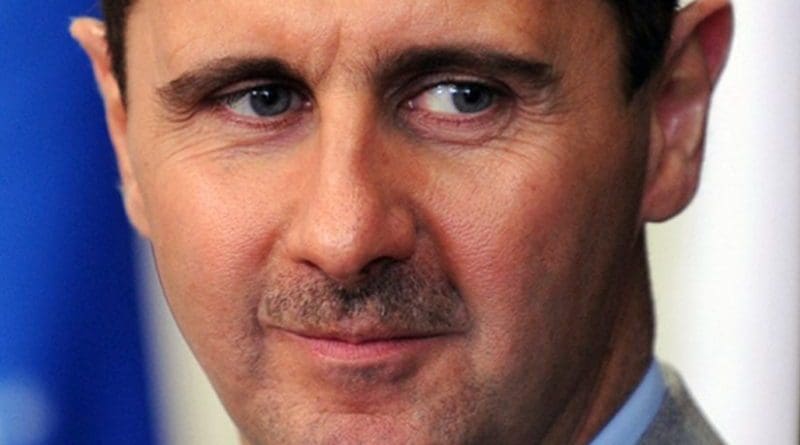

Assad’s Fateful Choice – OpEd

By Syria Comment - Joshua Landis

By David W. Lesch*

This spring marks the fifth year anniversary of the events that launched a civil war in Syria. Typically, there were some huge miscalculations early on that set the conflict in motion, such as the Syrian opposition’s expectation that the West would militarily intervene to facilitate the overthrow of the regime of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad. And then there was the West’s mistaken assumption that Assad would be the next domino to fall following the exits of dictators elsewhere in the Arab spring. Expecting this led to calls for Assad to step down, thus backing the West into a corner regarding a negotiated settlement once it became clear the Syrian president wasn’t going anywhere anytime soon. From the regime’s perspective, it made war the only choice.

But it is important to remember that the first—and biggest—mistake occurred at the onset, when Assad made the decision to crackdown harshly on the popular protests rather than offer real concessions. Indicative of this was Assad’s speech to the nation on March 30, 2011, his first to address the rising tensions. This was a seminal moment in modern Syrian history. The whole country, supporters and opponents, waited with bated breath to hear what he had to say. Syrians believed this would be the moment when Assad would finally live up to expectations.

From interviews I have conducted with current and former Syrian officials close to Assad and involved in the speech preparation, there were pronounced differences and confusion within the regime inner circle over how to react to the crisis. Several indicated that talk of internal coup was in the air…and not just potentially against Assad should he make the wrong move. One recommended that Assad himself should carry out a coup against hard line elements. Assad’s response was simply, “you are naïve.” Another former top official blatantly accused Baath party members of being in cahoots with security forces to use the crisis as an opportunity to force out the more reformist elements in the regime. Clearly there was intrigue at the top during this critical period, and Assad had to navigate his position—and response—very carefully.

As a result, there were different versions of the speech. One confidante of Assad saw a draft only a couple of hours before the speech was delivered. What he saw was relatively mild, concessionary and pro-reform. He believed this was what Assad was going to deliver. He was later shocked when he heard the much harsher version of the speech. Syrian government officials reportedly even sent snippets of the speech to reporters in the West that reflected a more pro-reform platform.

As we know, Assad’s speech was defiant, framing the crisis by blaming the uprising on insidious terrorists supported by Syria’s external enemies. Asad was taken to task in the international media for what was viewed as a blatant misdirection from the real socio-economic and political factors behind the protests. Either this or Assad was numb to the real causes of the uprising, blinded by a conceptual paradigm that defined the nature of threat to Syria in a profoundly different way. The speech proved to many Syrians that he was just another dictator. A top pro-Assad Hizbullah figure told me: “Bashar had real popularity in Syria. If he had taken the proper measures…it would have made things better. He had to take the decision to confront some clans inside the leadership…and I think he could have. This would have divided the ranks of the opposition, and he would have had a larger popular base.”

This is perhaps the saddest part of the story. Instead of resorting to the dictator’s survival handbook and succumbing to the convulsive reaction of the security state, Assad could have avoided civil war. As one former top Syrian official said of Bashar: “He was tilting on both sides. At some point they [the security chiefs] must have told him to just move aside, relax, and we’ll deal with it.” They figured the protests could be put down in a matter of weeks and then return to the status quo ante. Reality was much more nuanced.

As a result of amped-up Russian support, and as the re-taking of Palmyra from the Islamic State has shown, Assad has now secured his position for the time being. The popular protests that sprang to life recently during the cessation of hostilities, however, suggest that the opposition to Assad has not dissipated despite a half-decade of war. Indeed, the regime grossly underestimates how much the Syrian population has moved on, empowered by living five years without the state. If the regime wants to start a long healing process, Assad will have to find the courage he lacked in 2011 by accepting a managed transition of governance, which at the very least will significantly reduce his power. To do so he will have to fight against his authoritarian instincts—and possibly against hard liners. If past is prologue, this is wishful thinking.

But with Russia’s announcement to withdraw some of its forces from Syria, Assad has been put on notice. He is on the diplomatic hot seat, and he must choose how he gets off of it. He can continue to fight armed with the delusion that he can re-conquer all of Syria. Or maybe those officials who are still in the government who wanted him to deliver a softer version of his 2011 speech, chastened by the reality of what Syria has become, can form a critical mass of pressure on Assad to make the right choice this time around. They reflect that part of the regime—and Assad—who may be looking for a way out of this, satisfying their Russian patron while holding on to enough power. The West failed to understand the various competing factions inside the Assad regime back in 2011. Let’s not make that mistake again moving forward with whatever peace process emerges, because I am convinced that given the current state of affairs—and a with a great deal of diplomatic massaging—there is a formula of governance out there to be found and negotiated.

About the author:

*David W. Lesch is the Ewing Halsell Distinguished Professor of History at Trinity University in San Antonio, TX and author of “Syria: The Fall of the House of Assad.”

Source:

This article was published at Syria Comment.