China And Indonesia: A New Tug-Of-War – Analysis

By Observer Research Foundation

Indonesia is increasing its military presence in the region and upgrading its forces in the Natuna Islands as it seeks to challenge China and maintain its control over an important sea domain containing abundant marine food and energy resources.

By Pinak Ranjan Chakravarty

China and Indonesia have started a new tug-of-war over the latter’s declaration of intent to rename its 200-mile exclusive economic zone north of the Natuna Islands the “North Natuna Sea”. China has been quick to protest and has demanded that Jakarta drop the new name, stating that the move is not “conducive” to the excellent relations between the two countries. It has also issued passports that include an official map claiming part of the Natuna Islands, a part of the Riau province of Indonesia. China’s foreign ministry has claimed in its protest note that there are overlapping claims in the area and renaming of the sea will not alter this fact. China also asserted that changing an “internationally accepted name” has led to “complication and expansion” of the dispute and undermined peace and stability in the region.

In an interesting historical twist, observers have noted that Indonesia informed the International Hydrographic Organisation, a United Nations affiliated body, when the country renamed this southernmost part of the South China Sea as the Natuna Sea in 1986. There is no record of any Chinese protest when that happened.

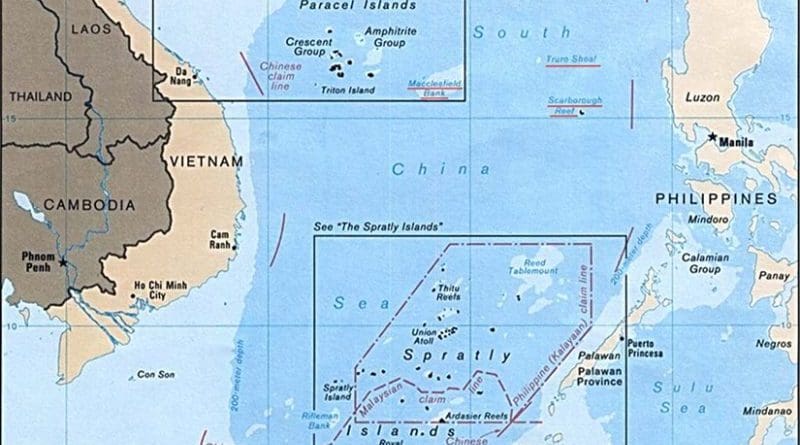

The Chinese protest is a shot across the bow for Indonesia. China’s unilateral claim to vast swathes of the South China Sea, as part of its so-called nine-dash line, has created tension and confrontation with almost all littoral nations. North Korea’s nuclear posturing and continuing barrage of missile tests and Donald Trump’s bellicose reaction have kept Asia on tenterhooks. The UN sanctions imposed recently on North Korea have dampened the rush to conflict. Whichever way one looks at these disputes in Asia, the common factor is China. China’s island grabbing spree led to an international arbitration in a case filed by the Philippines in their bilateral dispute under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea. China lost the legal argument over jurisdiction and rejected the verdict of the international arbitration court which trashed China’s nine-dash line and upheld the claims of the Philippines.

In a new map issued by the Indonesian maritime ministry, the North Natuna Sea was shown clearly, indicating that the Indonesian government led by the president, Joko Widodo, had approved these changes. Widodo’s government has a stated policy of establishing greater connectivity and control over the vast archipelago nation, consisting of over 17,500 islands and the adjoining maritime domain. Adding to the tension is the ambiguous nature of Chinese claims near the Natuna Islands. Indonesia believes that China’s nine-dash line overlaps with the Indonesian EEZ. Chinese officials had conceded in 1994 and again in 2015 that the Natuna Island group, located 300 kilometres from the northwest tip of Borneo, belongs to Indonesia.

Indonesia alleges that China has prevaricated on Indonesian requests for the clarification of China’s claim line. This seems to be a classic Chinese tactic to obfuscate this and simultaneously push at other nations with whom it has territorial disputes. China’s reluctance to demarcate the line of actual control with India is also not too dissimilar a strategy, under which China nibbles away at the border, creating facts on the ground and extending its claim. India’s chief of army staff has called it China’s “salami slicing tactic”.

China’s ultimate goal of becoming a great power is to be achieved by first intimidating and cowing down Asian nations into accepting China’s primacy as a first step. China has provoked clashes with Indonesia over the issue of Chinese traditional fishing rights in the Indonesian EEZ and Chinese coastguard ships have even intruded into Indonesia’s territorial waters to forcibly rescue Chinese fishing boats detained by Indonesia. The UNCLOS does not recognise ‘traditional fishing rights’ which are usually negotiated and agreed bilaterally.

For many years Indonesia played down any dispute with China in the South China Sea, though its fellow members in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, Brunei, Malaysia, the Philippines and Vietnam, all had running disputes with China. In 2016, Indonesia was involved with at least three major maritime skirmishes within its 200-mile EEZ with China, near the Natuna Islands. In June 2016, after the third skirmish, China claimed for the first time that it’s so-called nine-dash line included “traditional fishing grounds” within Indonesia’s EEZ.

The Widodo government has adopted a proactive policy of cracking down on illegal fishing in its maritime domain. Indonesia’s assertion of its rights has bumped up against China’s unilateral claims in the South China Sea. China’s recent claims of traditional fishing rights indicate that it is prepared to contest Indonesia’s claims to the EEZ. China is a voracious consumer of fish and is also eyeing energy resources locked up in energy deposits in this area.

This latest cartographic punch is a signal from Indonesia that it is willing to go beyond the earlier equilibrium and harden its position on the nine-dash line which it has never recognised. Not just Indonesia, but the Philippines and Vietnam refer to parts of the South China Sea as the West Philippine Sea and the East Sea. Indonesia’s claim may be on strong legal grounds, but it has no commensurate military capability to challenge China. Widodo’s government has struggled with balancing its considerable and converging economic interest with China and dealing with differences with that country.

There remains a clear perception of a Chinese threat in the region and the tension that this generates creates instability. As China indulges in brinkmanship, simultaneously increasing its economic engagement in the region, the chances of miscalculation rise. China’s assertiveness, however, is compelling other nations to push back to protect their own interests. Indonesia is increasing its military presence in the region and upgrading its forces in the Natuna Islands as it seeks to challenge China and maintain its control over an important sea domain containing abundant marine food and energy resources.

One reason for this policy option has been the impotence of ASEAN, the 10-member regional organisation which has watched helplessly as China keeps spreading its hegemony in the South China Sea. The ASEAN’s fond hope that China will keep its promises has gone up in smoke. China has been playing around with a delaying strategy with Asean regarding the code of conduct. All attempts by the grouping to finalise a new code of conduct have failed because China has effectively divided the Asean into two camps — one with maritime disputes with China and the other with no disputes in the maritime domain. The India-China standoff at Doklam had a message for other Asian countries. It is tempting to think that Indonesia has reached the same conclusion as India regarding dealing with China’s “salami slicing tactic”.

This article originally appeared in The Telegraph.