Do Occupational Licensing Laws Respect Human Rights? – OpEd

By Tyler Bonin*

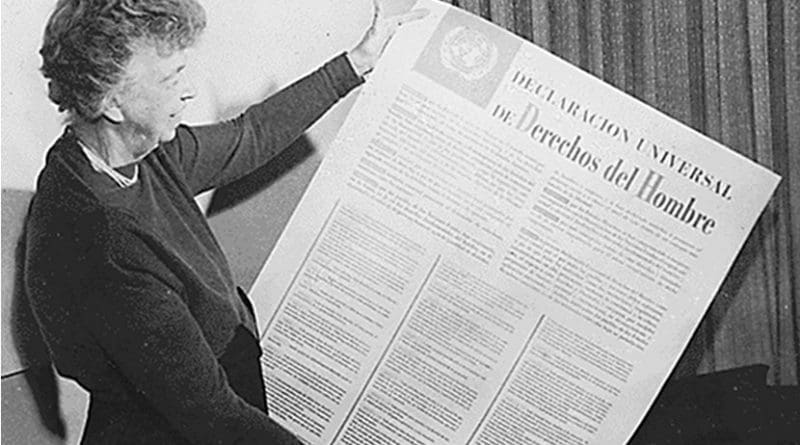

October 24 marked the anniversary of the United Nations charter, which formally established the intergovernmental organization as a replacement for the League of Nations. After its initial creation, the UN General Assembly adopted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), which is comprised of thirty articles outlining fundamental freedoms. While not binding, this document has served as the basis of many national constitutions and has been used as an accountability mechanism for treaties. However, one could argue that the right to livelihood (UDHR art. 23, section 1) – which states, “Everyone has the right to work, to free choice of employment, to just and favourable conditions of work and to protection against unemployment” – has been interpreted arbitrarily, especially in the United States, due to the widespread acceptance of barriers to employment such as occupational licensing laws.

Occupational licensing laws harm workers, as well as consumers who purchase services from professionals that require licensure. This harm is disproportionately placed on economically disadvantaged populations. Thus, when examining the effects of excessive occupational licensing in the U.S., it becomes apparent that these laws present an undue burden on one’s right to livelihood.

In the U.S., the number of occupations requiring licensure from state governments rose by nearly 25 percent between the early 1950s and the year 2008. Governments usually cite licensure requirements as necessary to protect the health and welfare of its citizens, as well as for providing increased consumer protection. The types of licensure requirements vary from state to state and today cover a myriad of professions. Everything from dentists and doctors, to interior designers and florists, require licensure in many states. The disparity in license requirements hampers professional mobility across state lines, as well. In fact, the very existence of wide-ranging professional requirements among the states speaks to the capricious nature of licensing boards. Licensure requirements have thus served as a cartel, or a form of professional protectionism.

This is on display in the case of St. Joseph Abbey v. Castille. The monks of St. Joseph’s in Covington, Louisiana, had been successfully producing wooden caskets for years, with the sales sustaining the abbey. Funeral industry leaders manning the Louisiana State Board of Embalmers and Funeral Directors deemed this dangerous to the public. Licensure requirements mandated by the board placed a strange burden on casket makers, requiring coursework and unrelated embalming training and apprenticeships. The government requiring carpenters to engage in training within a completely different field is not, by any use of logic, an attempt to protect the consumer. It is clearly a form of cronyism. Further illustrations of strange licensing requirements have been laid out by Joseph Sanderson in Yale Law’s Journal on Regulation.

What of protecting public health? Well, many state boards have attempted to shut down competition using the smokescreen of public health safeguards. The North Carolina Board of Dental Examiners attempted to shut down teeth whitening enterprises within the state in 2015, saying individuals running teeth whitening centers were practicing dentistry without a license and were thus criminals. The board even went so far as to place pressure on mall owners to cancel the leases of teeth-whitening kiosks. The state dental board consisted almost entirely of dentists who were, in turn, elected by other dentists. The appearance of such an action to stamp out teeth whitening was less a move to protect public health than it was an attempt to protect dentists’ bottom line. Based on a case brought against the North Carolina Dental Examiners’ board by the Federal Trade Commission, the Supreme Court ruled that licensing boards consisting of active participants within the profession they regulate do not enjoy antitrust immunity.

An increase in occupational licensing thus not only encourages rent-seeking, which enriches professionals by pushing out competitors, but also does real damage to workers looking for jobs. In this way, they increase unemployment. “In most occupations, licensing appears to confer a substantial advantage in terms of being able to quickly find and retain employment ,” notes Ryan Nunni n a paper from the Brookings Institution. In fact, workers within fields such as education and construction were found to be two percent more likely to be unemployed than their licensed counterparts within the same field, controlling for recognizable differences between such workers. Crowding of workers thus exists within industries that do not require licensing, and scarcity of workers exists in fields that do require licensing. It’s no economic secret that when demand is greater than supply in a labor market, wages increase.

Barriers to entry that exist in terms of costly and time-consuming procedures needed to obtain a license also harm workers within vulnerable populations. The opportunity costs involved in spending time and money in pursuing a job requiring a license are much higher for workers of a low-income status.

Furthermore, state governments often prevent individuals from obtaining a certification due to a previous criminal conviction. Approximately 70 million Americans have a criminal conviction of some sort. Individuals have often been barred from obtaining a license because of convictions, many of which have been non-violent or misdemeanors. Such is the case with Sonja Blake, who lost her livelihood after the state revoked her childcare license because of a change in law involving criminal records and childcare licensing. Ms. Blake had a misdemeanor conviction but ran her business for a decade without incident, until the state shuttered her doors. These types of policies destroy livelihoods, and the loss of livelihood often destroys lives. These policies ultimately violate one’s ability – and, under the UDHR, right – to provide for self and family.

When considering the crony/protectionist measures underlying licensure policies, it becomes clear that state governments violate the rights of citizens in order to benefit more powerful actors, who use government leverage to promote their personal interests. Protectionist policies hurt the public at large by depriving consumers of access to services and forcefully removing free choice of employment. In these instances, no true free market exists to allow coordination between employers and those within the labor market. The subsequent market distortions have profound impact. Perhaps states should rethink these policies, in light of ensuring citizens the right to a peaceful, healthy life.

About the author:

*Tyler Bonin is a teacher at Thales Academy, a classical school in North Carolina.

Source:

This article was published by the Acton Institute.