Drones: A New Chapter In Modern Warfare – Analysis

By INEGMA and Dr. Theodore Karasik

By Justin D. Wallestad and Dr. Theodore Karasik

Less than a month had passed since the United States mourned the victims of 9/11 when American born al-Qaeda cleric, Anwar al-Awlaki, fell neither at the hands of Yemeni authorities nor through the swiftest measure of justice dragged out in the courtroom. No, al-Awlaki experienced death from above; from an unseen ‘enemy’ once considered a neighbor of sorts, but now thousands of miles away. It should come as no surprise that the targeted killing of al-Awlaki, more precisely the CIA drone strike on his vehicle well within Yemeni borders, has become highly politicized – the limelight perhaps – behind this new chapter in modern warfare.

Whether or not one agrees with the legality over the use of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs), and by extension its sister-program, Unmanned Combat Vehicles (UCVs), these drones are here to stay, growing ever more popular among nation-states seeking to maintain relevancy and security in an age of robotic warfare.

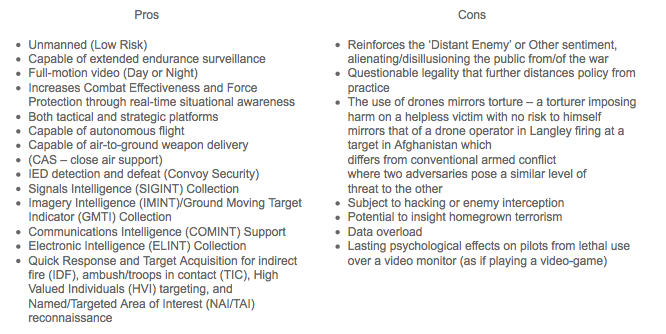

The following graph outlines a rudimentary list of pros and cons behind drone usage compiled from various open-source outlets to include manufacturing brochures and leading opposing arguments with attention given to international law; however, drone use remains heavily debated.

From Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance (ISR) to precision targeting, drones continue to evolve, pushing the envelope on the conduct of war to new dimensions and forcing the international community to once again come together and determine whether this venture is worth the risks as drone usage spreads beyond the Durand Line and into the realm of future international and domestic law enforcement capabilities.

A Window of Opportunity: The Global War on Terror

The concept of a pilotless aircraft is not particularly new in our understanding of contemporary warfare; the first drone dates back to 1919 when such a device successfully sunk a German battleship. Since then, limitations on command and control platforms – especially throughout the Vietnam era – restricted unmanned aerial employment until the 1990s when improvements in satellite communications and navigation capabilities dramatically enhanced the range and flexibility of modern drones. Former U.S. President H.W. Bush witnessed the Pioneer preform more than three hundred missions in search of scud missiles during the Gulf War while former U.S. President Clinton deployed drones over the Balkans during Operation Noble Anvil, revealing the vulnerability of contemporary UAVs to anti-aircraft methods. Nevertheless, these examples differ from the weaponized drones responsible for the death of Anwar al-Awlaki and present only half the story.

Two events are said to have contributed to this new chapter in pilotless aircrafts which began in February 2001 when the United States Air Force (USAF) successfully launched a missile from its Predator platform. Just one month following the September 11th attacks, Predator drones became increasingly weaponized for use in Afghanistan, marking the first recorded deployment of armed drones. Although there is little debate over the abundance of UAVs currently in service – estimated well within the thousands around the world – greater attention is given to the two dimensions of drone usage presently employed by the U.S. government. That is, the military use of armed drones in designated hostile territories verses civilian agencies acting in the name of national security, shrouded in secrecy, eliminating transnational terrorists wherever they lie.

Despite the profuse deployment of CIA drone raids within the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) of Northern and Southern Waziristan receiving the greatest level of international reprimand, the legality of military drone usage has remained relatively free from criticism. As of March 2011, the USAF has devoted more assets to the training of UAV pilots than conventional planes based on a basic cost to benefits ratio; a Predator costs $4.5 million and presents little to no risk to personnel while a F-22 Raptor fighter jet approaches $150 million and requires an ample amount of technical experience. The Pentagon’s proposal to set aside $5 billion in the 2012 budget solely for the production of drones – an industry already estimated to be worth $7 billion in the Asia-Pacific alone – demonstrates the escalating view that drones provide a strategic advantage in the advancement of national security objectives despite potential political reprisal and moral complications that some cite as exacerbating the insurgency problem.

Attack of the Drones: Losing the War for ‘Hearts and Minds’?

There is no denying the counter-productive side effects of launching a global effort to thwart al-Qaeda and its affiliates from behind a computer monitor or ‘eyes from the sky.’ While the Bush administration reportedly conducted a measly forty-five drone attacks in Pakistan throughout his eight years in office, the current administration is reportedly responsible for executing 118 drone raids in 2010 alone, destroying potential intelligence gathering capabilities that would otherwise be exploitable through conventional detainment (e.g. interrogations, pocket litter, and mobile devices). UAVs simply conducting routine ISR missions are so awash with imagery data that analysts are finding it increasingly difficult to continue with the up-tempo as Iraqi militants in 2009 were able to intercept Predator video-feed with $26 software.

Legal journals have pointed to the moral implications of reducing human life to targeting terms, comparing the act of firing a hellfire missile from behind a monitor screen to picking up a controller for the latest game-console. Others have taken the ethical approach by underlining the unsettling similarities between how a drone operator from Langley can inflict harm on someone half-way around the world with no direct repercussions as compared to a person participating in the torture of a helpless victim at no risk to himself.

Even so, the past decade has taken its toll on the international community’s continued commitment to maintain a physical troop presence in Afghanistan and elsewhere. Preparations for the gradual withdrawal of armed forces have pushed drones into the forefront of the battlefield and inadvertently reinforced the perception of a ‘distant’ enemy. Poorly executed drone raids undoubtedly increase the potential for unforeseen collateral damage that risks alienating those within the affected population who support the proposed end state. Even the general public of the so-called aggressor is in danger of becoming disillusioned by any progress, or lack thereof, made by excessive use of drones to target key figures of the insurgency. The failed Times Square bomber, Faisal Shahzad, is a case in point. After witnessing the drone attacks in Pakistan first-hand during a five-month visit, he joined a growing number of homegrown U.S. terror suspects to include Najibullah Zazi, a U.S. resident and Afghan immigrant who pleaded guilty in 2010 for plotting an attack on New York’s subway system and U.S.-born Major Nidal Malik Hasan, responsible for the 2009 Fort Hood, Texas, shooting.

Despite growing concerns surrounding the use of armed drones, UAVs have contributed and will no doubt continue contributing to the advancement of national security objectives. In 2002, six persons reportedly connected to the USS Cole bombing from late 2000 fell victim to the Predator’s hellfire within Yemen. Following two major PKK cross-border ambushes in southeastern Turkey – resulting in a mass gathering of Turkish military along its Iraqi border in 2007 – led the U.S. to offer real-time drone coverage of Kurdish-PKK operatives in order to persuade Turkey away from invading northern Iraq and potentially disrupting essential supply lines. The CIA reported in 2009 that more than half of its High Valued Individuals (HVI) were successfully put down by its drone program in Pakistan; among them was Sheikh Ahmed Salim, responsible for providing the trucks used during the 1998 U.S. embassy attacks in Dar Es Salaam and Nairobi, Tanzania and Kenya respectively. The civilian death count in Pakistan is also said to have declined in 2010 due to more diligent intelligence, greater target acquisition, smaller payloads and translucent cooperation from within Pakistan.

Drone use during the Libyan intervention earlier this year and domestic law enforcement in Texas, Colorado, Florida and the U.S. Department of Homeland Security are prime examples of the increasing role drones will play in the future. Even the Australian and United Kingdom police departments have expressed interest in receiving similar accommodations, only working to strengthen arguments for the benefits of drone use over their proposed costs.

Drones of the Future: Redefining ISR Capabilities

The Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance (ISR) capabilities of drones are unprecedented; for months the CIA gathered high-resolution video of Osama Bin Laden’s compound using high-altitude UAVs before the Navy Seals carried out its May 2nd assault. As unmanned aircrafts, drones are capable of extended endurance surveillance of High Valued Individuals (HVIs), Named/Target Areas of Interest (NAI/TAI), and even autonomous flight, collecting full-motion video, day or night.

Launched from either tactical or strategic platforms, drones maintain a diversified portfolio in providing real-time situational awareness, capable of being outfitted with specialized equipment in support of Signals Intelligence (SIGINT), Measurements and Signature Intelligence (MASINT), Imagery Intelligence (IMINT), and Ground Moving Target Indicator (GMTI) collection, among others in the assistance of military commanders and policymakers in making more informed decisions and going as far as increasing the combat effectiveness of foot-soldiers and force protection of base security. Drones promote convoy security with Improvised Explosive Device (IED) detection and defeat mechanisms, promptly respond to Indirect Fire (IDF) points of origin or impact for damage assessments, and offer Close Air Support (CAS) through the deliverance of air-to-ground weaponry at the onset of Troops in Contact (TIC). Drones are not limited to military functions, however; civilian use even extends beyond simple law enforcement surveillance and allows for greater search and rescue capabilities in remote and isolated regions as well as areas affected by radiation or hazardous conditions.

As the use of drones becomes increasingly paramount, innovations will lead to more precise targeting identification and by extension, mission execution. Although the manner by which targets are presently marked for elimination is worth further review, drones represent the future in modern warfare. As such, drone usage will undoubtedly experience legal challenges in the wake of international pursuit to restrict the scope of their employment; though, just as the conduct of war has undergone legal standardization, so too will the future implementation of drones. But until then, remaining ahead of the curve in ISR, and its weaponized counterpart, has the world focused on these unmanned aircrafts.

Authors:

Justin D. Wallestad, INEGMA Fall 2011 Intern

Dr. Theodore Karasik, Director of Research and Consultancy, INEGMA