Gender Inequality And State Fragility In The Sahel – Analysis

By FRIDE

By Clare Castillejo*

There is increasing commitment among international actors to integrate a gender perspective into support for fragile and conflict affected states (FCAS). This commitment is expressed in the United Nations Security Council Resolution (UNSC) 1325 on women security and peace (SCR 1325), which calls for ‘women’s equal participation and full involvement in all efforts for the maintenance and promotion of peace and security’; in the New Deal for Engagement in Fragile States, agreed by fragile countries, development partners and international organisations in 2011, which states that ‘the empowerment of women […] is at the heart of successful peacebuilding and statebuilding’; and in the policies of numerous multilateral and bilateral donors. However, despite these commitments, in practice international engagement in FCAS frequently overlooks the complex connections and mutually-reinforcing relationship between gender inequality and the weak governance, under-development and conflicts that characterise these states.

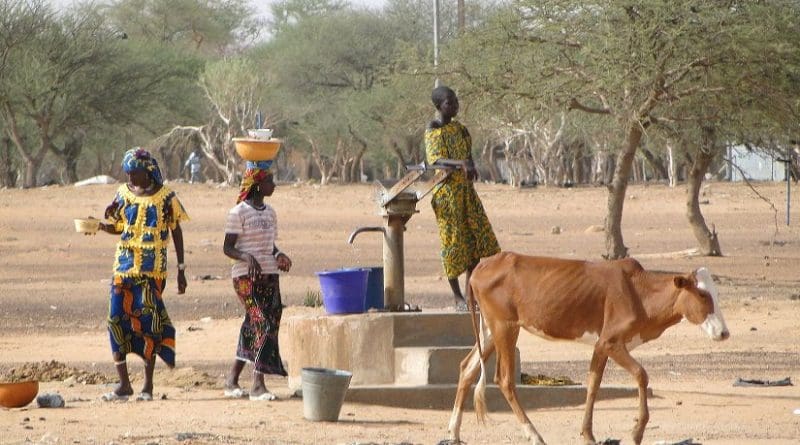

This oversight is particularly glaring in the Sahel. Sahelien states are not only deeply fragile, but also, according to the United Nations (UN), have the highest levels of gender inequality in the world. Across the region, women’s profound political, economic and social exclusion is both exacerbated by and contributes to fragility dynamics, and acts as a barrier to effective peacebuilding. The Sahel desperately requires an international response that takes gender seriously.

THE STATE FRAGILITY – GENDER INEQUALITY RELATIONSHIP

The Sahel is one of the world’s most under-developed regions. According to the World Bank, around half of the Sahel’s population lives on less than US$1.25 per day, while countries such as Niger, Chad, Mali and Burkina Faso remain stuck at the bottom of the UN’s Human Development Index. Women are particularly disadvantaged by a number of inter-twined factors such as the region’s extreme poverty; weak state institutions; lack of basic services; unstable, unaccountable and corrupt politics; and highly patriarchal social structures. Given this context, progress on women’s rights in the Sahel has been very limited compared to elsewhere in Africa. Out of 152 countries on the UN Gender Inequality Index, Niger ranks 151, Chad 150 and Mali 148.

According to the UN, the Sahel faces four over-lapping crises – political, environmental, developmental and humanitarian – all of which are worsening gender inequalities. UN Women describes how, across the Sahel, ‘women are caught up in vicious cycles of chronic poverty, environmental stress and deprivation, denial of their basic rights and different forms of violence are compounded by the overlap of harmful traditional practices, social constructs and religious fundamentalism’.

In recent years, governance has atrophied and violence has spiralled in the Sahel, as states have failed to live up to the promises of democratisation; political, regional and ethnic grievances have intensified; upheavals in the Maghreb have fuelled insecurity in neighbouring Sahelien countries; and transnational criminal networks have expanded their presence. This deteriorating situation has a direct impact on women’s security, as most horrifically illustrated in the violence experienced by women in Mali during the 2012 crisis, or today in Northern Nigeria at the hands of Boko Haram. However, it also has more insidious effects on women’s rights. Grievances over the failure of Sahelien states to deliver democracy or development have led to a rise in radical Islamist opposition movements across the region, whose growing political and social influence is under- mining hard-won gains in women’s rights. Indeed – as in many FCAS – Sahelien women’s rights are increasingly caught up in broader political contestations over the nature of state and society.

Not only does fragility negatively affect women’s rights, but gender inequalities in the Sahel also fuel fragility. Most obviously, these inequalities contribute to both rapid population growth and continued under-development. It is now widely recognised, as detailed in the World Bank’s 2011 World Development Report, that ‘greater gender equality can enhance productivity, improve development outcomes for the next generation, and make institutions more representative’. In addition, recent academic research, such as that emerging from Uppsala University in Sweden, demonstrates significant links between high levels of gender inequality and high levels of intra-state armed conflict, in part because of macho social attitudes.

Women’s political participation

Women in the Sahel are highly excluded from political life. Sahelien women’s expectations that democratisation would significantly increase their political participation have been largely unmet. Across the region, women’s representation in parliament is 15 per cent, while in Mali it is just 10 per cent, in Niger 13 per cent and in Chad 15 per cent. Campaigns for the introduction of quotas for women in political office have faced extreme opposition from conservative religious groups. However, in some cases, this opposition has been overcome and meaningful quotas established. For example, in Senegal women now constitute 43 per cent of the national assembly, well above the average for developed countries, while in Mauritania they make up 25 per cent, similar to many European countries.

The nature of politics in the Sahel is a major barrier to women’s political participation. Political parties tend to be centralised around individual male leaders, to sideline women members within powerless ‘women’s wings’, and to be reluctant to field women candidates. Even where women are selected as candidates, they frequently lack the clientelist networks or financial resources required to mobilise or buy votes. Moreover, once elected it is difficult for women to influence decision making, as they face significant discrimination and lack access to the informal spaces and networks in which political deals are done. Women are rarely given senior political roles, although there have been surprising exceptions to this, with women briefly becoming prime ministers in Senegal in 2001 and Mali in 2011.

Excluded from formal structures, Sahelien women have built informal networks for political influence. A recent Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue report describes how Sahelien women have participated in REFAMP, a network of African women parliamentarians and ministers. In Burkina Faso, Nigerien and Senegalese women have formed cross party associations to press for greater representation of women in politics. However, it is within civil society – where the stakes are lower and clientelist networks less powerful – that women have had the greatest space to mobilise and channel their political voice.

Women’s political exclusion clearly contributes to exclusionary and unaccountable governance in the Sahel. It also means that women’s rights and needs are not policy priorities, with direct implications for achieving broader development goals. Critically, in some of the most troubled Sahelien contexts, including Mali, Northern Nigeria and Niger, conservative religious movements are increasingly preventing women from participating in public life.

Women’s rights within the family

Women’s family rights are a central area of contestation between governments, women’s movements and conservative religious forces in the Sahel. This mirrors dynamics seen elsewhere across North Africa, such as Morocco or Egypt, where family law reform has been a central battleground in power struggles between political elites and Islamist opposition.

Family law in most Sahelien countries is based on customary and Islamic law and gives women very few rights. Across the region, women have mobilised to demand reform of these laws, but have faced a backlash from conservative forces. For example, in Mali a 2009 draft family code that would have increased the age of marriage to 18, given daughters inheritance rights and recognised women as equal to their husbands, was abandoned due to pressure from the High Council of Islam in Mali and religious groups. In Niger, an attempt to reform family law in 2011 was also abandoned under pressure from Islamist associations.

A recent Wilson Center report outlines how fam- ily law in Northern Nigeria is caught up in broader struggles over religious, regional and political identities. It describes how women activists negotiate the contestation between Islamist and secularist Nigerian identities by using both sophisticated religious interpretations and Nigeria’s constitution and human rights commitments to promote their rights.

While women’s status within the family is often presented as pertaining entirely to the personal sphere, it has profound implications for broader development and fragility dynamics. Such disempowerment at household level limits women’s ability to access services, economic opportunities, or resources such as land; to participate in public life; or to escape abuse. Discriminatory family laws therefore prevent women from contributing effectively to political and socio-economic development and stability, and contribute to the population pressures discussed below.

Education and population

The Sahel has some of the world’s worst indictors in terms of women’s education, with literacy rates across the region much lower for women than men. For example, in Niger literacy among 15-24 year olds is 52 per cent for men compared with 23 per cent for women. A major factor limiting girls’ access to education is early marriage, with the average age of marriage being 15.7 in Niger, 16.6 in Mali and 17.1 in Mauritania. According to a recent report by Mireille Affa’a-Mindzie for the International Peace Institute, this situation is exacerbated as ‘girls education is further weakened by the growing conservative religious trend’. For example, in Niger in 2012 religious groups blocked legislation that would have helped protect schoolgirls from early marriage by raising the age of compulsory education from 12 to 16. The denial of girls’ right to education clearly reduces their personal autonomy and their ability to contribute fully to economic, political and social life. It also contributes to the region’s high fertility rates.

Although countries such as Chad, Mauritania, Burkina Faso and Niger are experiencing some of the world’s highest economic growth rates, this is not translating into greater GDP per capita or enhanced well-being. A central reason for this is the region’s slow demographic transition – child mortality has fallen rapidly, but fertility rates have not. Niger has the world’s highest fertility rate, with an average of 7.6 children per woman, while in Chad the rate is 6.6 and in Mali 6.1. As a result, the UN predicts that the Sahel’s population will rise from the current 100 million people to 340 million by 2050. As the population expands in the context of constrained resources and livelihoods and increased impacts of climate change, population pressure can become a major driver of fragility. As the World Bank states, ‘the lagging demographic transition in the Sahel places the region at higher risk of extreme poverty, growing inequities, slower economic growth and […] instability’.

Evidence from around the world demonstrates that reducing fertility rates requires the provision of appropriate family planning services, and – crucially – empowering women to delay marriage and child bearing. Therefore, the Sahel’s population crisis cannot be solved while Sahelien women remain politically, economically and socially marginalised. As the United Nations Population Fund argues, ‘where choices improve for women and girls, fertility declines and opportunities expand [this can] set counties in the Sahel on the path to sustained, inclusive social and economic growth’. While Niger and Burkina Faso have adopted some limited policies to promote family planning, it appears that slowing population growth is not a serious priority for most Sahelien states.

WOMEN’S RESPONSE TO FRAGILITY AND CONFLICT

According to Affa’a-Mindzie, ‘although women [in the Sahel] are disproportionately affected by conflict, their protection in conflict-affected con- texts and their participation in conflict prevention and peace initiatives remain marginal at best’. For example, women have been largely excluded from both national and international peace processes in Mali, despite their vocal demands for inclusion. Where there have been efforts to include women in peace activities, such as those supported by the Nigerien High Authority for Peacebuilding, these are very much at the margins of real political processes.

This exclusion from formal peacebuilding processes reflects Sahelien women’s exclusion from broader political life. It inevitably impoverishes such processes, with neither women’s knowledge nor interests being taken into account.

Exclusion from formal processes has not stopped Sahelien women from mobilising at regional, national and local level to address conflict. For example, the pan-African non-governmental organisation (NGO) Femmes Africa Solidarité works across the Sahel to promote a women, peace and security agenda. Likewise, regional and nation- al women’s organisations came together in Senegal in 2012 to support a non-violent election, including by mobilising female election monitors. During the conflict in Mali, women lobbied peace negotiators in Ouagadougou and West African heads of state, demonstrated for peace, and in some places engaged in mediation with rebels.

However, women’s organisations face significant challenges in mobilising effectively in response to conflict. These relate both to the insecure and discriminatory environment, and to the weakness and divisions within Sahelien women’s movements. Not only do women’s organisations face serious capacity and financing constraints. They are also inevitably fractured by the same political and social cleavages (ethnic, religious/secular, class based, rural/urban, etc.) that divide the rest of society, which have limited their impact.

Critically, women’s organisations are often over-looked by international actors. International funding for them is mostly small, piecemeal and generally does not support them to develop a strategic agenda. Moreover, international actors’ inevitable focus on engagement with male power holders means that they often do not appreciate the value of listening to women’s voices. In fact, as Lakshmi Puri, deputy executive director of UN Women, points out ‘women’s perspectives on tensions in social relations, their awareness of threats to personal, family and community security, are critical elements of stability and conflict prevention and constitute some of the most effective early warning systems’.

THE INTERNATIONAL RESPONSE

There is growing evidence that placing gender issues centrally within peacebuilding and statebuilding processes, including by meaningfully including women in such processes, improves peace and stability outcomes. Conversely, peacebuilding and statebuilding processes can provide important opportunities to address entrenched gender inequalities and enhance women’s rights, as state-citizens relations are renegotiated, power is redistributed and institutions are reformed. The Sahel, plagued by extreme gender inequality and state fragility, requires an international response that links peacebuilding, statebuilding and gender equality. Yet, the international community has largely failed to provide one.

Across the Sahel, there are a range of internationally supported initiatives to address women’s needs, tackle gender inequalities and empower women. International actors support a wide range of services provision for women and girls. They undertake activities to promote women’s political voice and participation, such as funding women’s civil society organisations, building the capacity of women in politics, and supporting national and regional coalition building. While more limited, there have also been international initiatives to support women’s engagement in peacebuilding, such as support for women’s regional peace networks and training of women mediators. Notably, in 2013 the European Union’s (EU) External Action Service (EEAS) and the UN hosted a conference on women’s leadership in the Sahel, which focused on conflict and stability.

While such activities may be valuable, they tend to be small, underfunded and – critically – disconnected from each other and from broader efforts to address Sahelien fragility and development challenges. The Sahel’s complex problems require a response that is both genuinely multidisciplinary – connecting actors working across development, security, political, and humanitarian fields – and that meaningfully integrates gender throughout. Such a response would enable international actors to better understand and address, for example, connections between failing governance, the rise of extremism, girls’ access to education and age of marriage, population pressures, and security challenges related to conflict over resources or wide- spread youth unemployment.

International actors’ strategies for engagement in the region illustrate their failure to recognise the centrality of gender to achieving broader goals. While the EU supports some gender related activities in the Sahel through its development and humanitarian assistance, the 2011 EEAS Strategy for Security and Development in the Sahel makes no mention of women, gender or the region’s pressing population challenges. This absence is disappointing given that the EU Consensus on Development identifies gender equality as one of the five essential principles of development cooperation. Meanwhile, in the UN Integrated Strategy for the Sahel gender is mainstreamed throughout the first strategic goal on governance, but entirely absent from the other two goals on security and long-term resilience.

The fact that gender remains peripheral for many international development and security actors is not unique to the Sahel. This situation is common in FCAS because of trade-offs between addressing the priorities of local elites and promoting international norms, as well as lack of leadership, knowledge, skills and incentives on gender among international staff and failure to include gender in political analysis. Indeed, a 2010 Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) study on aid allocations for gender equality in fragile states conclud- ed that donors are not living up to their international commitments in this area.

CONCLUSION

Addressing the Sahel’s multiple challenges requires recognising the centrality of gender to political, security, development and sustainability outcomes for the region. It also requires greater strategic prioritisation, funding and human resources dedicated to gender issues by both international actors and local governments. Sustained support is needed for Sahelien women to mobilise, develop their own agendas, and participate in decision making. Greater attention must also be paid to advocacy with male political leaders on gender issues, as well as addressing sources of resistance and backlashes against women’s rights.

Promoting gender equality is not an add-on but a must in the Sahel. As leading scholars from the University of California, Berkley, argue in a recent report, ‘investing in women […] is probably a more predictable way of preventing conflict over resources (as is currently occurring in Dar- fur), or the proliferation of terrorist cells (as has taken place in Mali) than military action. It is a slower way of defusing conflict or pre-empting the rise of fundamentalism, but a more sure one’.

About the author:

*Clare Castillejo is senior researcher at FRIDE.

Source:

This article was published by FRIDE as Policy Brief 204 (PDF)

This Policy Brief belongs to the FRIDE project ‘The Fragile Sahel: A challenge for Europe’, carried out in cooperation with the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. We acknowledge the generous support of DIMES. For further information on this project, please contact Clare Castillejo ([email protected]).