Myanmar’s 2015 Elections: New Hope On The Horizon? – Analysis

By ISEAS - Yusof Ishak Institute

By Moe Thuzar*

The general elections held in Myanmar on November 8, 2015, though not without flaws, plainly signaled the beginning of a new hope for the country’s transition.

About 80 percent of 30 million eligible voters cast their votes in over 300 constituencies and 41,000 polling stations countrywide. In some 600 village tracts in areas of ongoing conflict, polling was cancelled. This, and the specter of violence in the campaign period, marred the otherwise highly charged atmosphere. Ninety-two political parties—60 of which were ethnic parties)—competed for 1150 seats in the upper and lower houses of parliament, and the local assemblies in the 14 administrative states and regions. These seats do not include the 25 percent of total seats occupied by serving military officers in all assemblies.

The campaign period began on August 8. Overseas polling stations were opened at Myanmar embassies across the globe and advance voting was also offered in-country to those with official missions or health issues. There was widespread optimism that the 2015 polls would be freer and more credible than past elections (1990 and 2010), and high hopes that a “genuinely civilian government” would successfully implement badly needed political, administrative and economic reforms. But there was also fear that the incumbent would somehow rig the elections. Although the election results have showed otherwise, this sentiment has some historical moorings.

ELECTIONS PAST AND PRESENT – A QUICK OVERVIEW

The 2015 general elections are the first openly-contested elections since 1990 when the National League for Democracy (NLD) led by Daw Aung San Suu Kyi won the majority of seats. That result was quickly negated however by the State Law and Order Restoration Council, the military junta that took control of the country in September 1988.

On 27 May 1990, 73 percent of 15 million eligible voters voted in the belief that the SLORC would honor its promise to transfer power to an elected government. With its win of 392 seats, the National League for Democracy (NLD) secured 79.8 per cent of the votes cast for the 492 seats up for grabs in the unicameral parliament. While the 1990 elections were not open to foreign observers, foreign media and journalists were allowed entry visas just days prior to the polls. The junta had highlighted that the elected representatives would form a constituent assembly that would draw up a new constitution for the country, and that a second round of elections would be held after that new constitution had been approved in a referendum. After an initial balking (apparently by the NLD’s “intelligentsia” group rather than the “veterans”)1 over this proposed drawn-out process, the NLD went along with the plan. Daw Aung San Suu Kyi was under house arrest at the time of the elections, and had expressed her concern that the constitutional process could “take months and months, if not years”2. Her prescient concern was borne out. It took more than 14 years from 1993 for the constitutional process to be completed, with several walkouts and hiatuses. The referendum itself was not free from controversy, taking place in the immediate aftermath of the devastating Cyclone Nargis in May 2008. During the long drawn-out constitutional process, the NLD left the discussion table3, and did not register for the November 2010 elections which were held under the framework of the 2008 Constitution.

The 2010 elections were thus an anti-climactic step that was seen by the military regime (which had changed its name to a less ominous-sounding State Peace and Development Council, or SPDC, in September 1998) as necessary for it to move forward with its professed seven-step roadmap to democracy. Compared to 1990, the 2010 elections were neither open nor fair. Of the 29 million eligible voters, 77 percent turned out to vote in candidates for the two houses of parliament at the Union level and for regional/state assemblies. For the first time in the country’s history, all parliamentary assemblies had 25 percent of their total seats reserved for non-elected military members. With the NLD not in the running, most of the votes cast for change went either to the National Democratic Force, a splinter group of the NLD, or smaller parties. There were no observers or foreign media, and the voting took place amidst widespread reports of rigging. The Union Solidarity and Development Party – which had transformed itself from the SPDC’s “people’s arm” Union Solidarity and Development Association, won with 76.5 percent of the overall votes. The National Unity Party, which had transformed from the former Burma Socialist Programme Party won the second largest number of votes, as it had in 1990.

The main element characterizing the 2010 elections can be summed up as apathy. This was deepest in what can be termed the educated middle-class, i.e., people with tertiary education, with exposure to the world and plugged in to events, with higher personal incomes and a degree of autonomy in their work. Many from this group decided not to vote because they believed that their votes wouldn’t count or because they had no confidence in the elections. There was also a certain show of support for the NLD’s boycott in the decisions not to vote. Yet, these intellectuals were also beset with angst over their

“abdication of responsibility” by not going to the polls. Civil servants seemed to have thought that they did not have a choice but to vote for the USDP, while former civil servants – some of whom had held quite senior positions – had no such compunctions and largely voted for change. Military personnel down to the rank and file, and their families, were expected to “make the correct choice”, i.e., vote for the USDP. Their votes were cast in advance. There was less emotion among the lower-income groups, who acted more out of so-called pragmatism. This was more evident in the provinces/rural areas where the promise of direct benefits in the form of improved roads, electricity, water and other amenities ensured the vote.

In the urban areas, the vote of the lower-income groups were divided among industry-workers and lower-ranking civil servants, and people like taxi drivers and rickshaw men. The former voted for the USDP because 1) they had to and/or 2) they hoped for direct benefits in living standards. The latter mostly wasted their vote because “they believed the elections were rigged for the army to win”. Apathy was prevalent among many first-time voters in the 2010 elections, who were not interested in the platforms of various political parties. Some tried the pragmatic approach and voted for “continuity”, citing reasons of “stability”. And then there were those who felt their votes counted to create a space – however small – for democratization. Theirs were the votes largely responsible for small numbers of opposition seats in parliament.

The scenario and sentiments in 2015 could not have been more different. First, the NLD was clearly back in the game, after rejoining the political process in 2012 and sweeping 43 out of 44 seats (45 available)4 in the by-elections of 1 April 2012.

There was also more political awareness and engagement by the electorate, who now had greater access to varied sources of information. First-time and repeat voters alike were keen to make their vote count for future generations, and were open about their desire for change. Citizens living overseas queued assiduously (in some cities, for days) to cast their vote at the overseas polling stations, and those who could, traveled home to vote. Red became the color of change, and people openly sported the NLD logo everywhere they could. Thus, the sense of anticipation surrounding the 2015 elections was similar to that in 1990. Myanmar’s Union Election Commission opened up the election process to international observers, some of whom arrived days ahead to monitor the campaign and to cover the polls in different parts of the country. Foreign and local media actively followed campaign trails.

Daw Suu – who had been under house arrest before and during the 1990 and 2010 elections – hit the campaign trail early. To a populace inured to decades of authoritarian rule, and in the most open space afforded in decades to voice views and opinions, the NLD’s campaign message of “It’s time (to change)” struck a resonant chord across all income groups and social backgrounds.

In contrast, the incumbent USDP, ran on a performance platform which seemed to indicate status quo. Deliverance of election promises made in 2010 had been uneven across constituencies. Nationally, the main performance deliverable that the USDP administration could focus on was the achieving of a nationwide ceasefire agreement with ethnic armed groups and starting political dialogue towards constitutional change. The significance of the nationwide ceasefire agreement signed on 15 October 2015 was diluted somewhat by the fact that only eight of the 16 armed ethnic groups came to the table as signatories. The only reform measure popularly received seemed to have been the privatization of the telecommunications industry which led to normalization of prices for mobile phones and cellular phone smart cards. This broadened public communication and information-sharing, and played a large part in spreading election campaign news widely, and in keeping track of polling results.

On the morning of November 8, keen voters were queuing at polling stations long before the opening hour of 6 a.m. Voter turnout was high, at 80 percent of 30 million eligible voters. Taking a page from other election experiences in Southeast Asia, voting ink was introduced for the first time in Myanmar, and voters displayed their ink-stained fingers proudly. Despite earlier concerns over possible election violence, voting was conducted with discipline. So, too, was the vote-counting process after polling closed at 4 p.m. Predictably, interest in the outcome of polls was largely focused on the two dominant large parties: the NLD and the USDP. In a bid for transparency, polling stations announced their respective results publicly. These were then shared widely by social media, thus allowing for real-time tracking of the results. They indicated a clear win for the NLD from the very start.

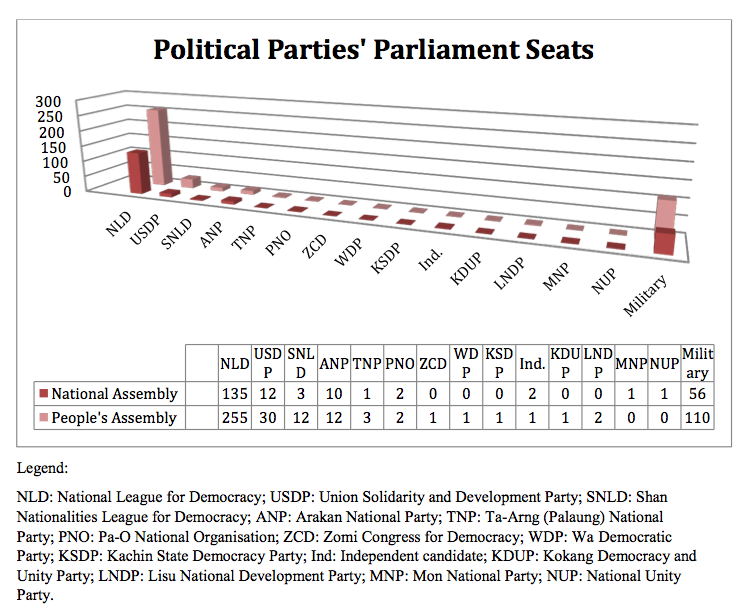

The NLD swept 390 of the 491 seats in both houses of parliament, a resounding 79.4 percent5. The USDP retained 42 seats, and the Arakan National Party came a distant third with 22 seats. The NLD thus holds the majority of seats in both houses of parliament: 59 percent of the 433 seats in the lower house (People’s Assembly or Pyithu Hluttaw), and 60 percent of the 224 seats in the upper house (National Assembly or Amyotha Hluttaw). The NLD also dominates with 476 of 629 seats across the 14 state/regional assemblies.

POST-ELECTION SENTIMENTS

The November 8 election results have set the stage for a second election in parliament in early 2016 to choose the top three executive positions (president and two vice-presidents). Both houses of parliament, and the military bloc, will each nominate a candidate.

The candidate with the largest number of votes will be confirmed as President, with the two runners-up taking each of the two vice-presidential posts. With its parliamentary majority, the NLD looks set to bag the president and one of the vice-president positions. The USDP, with some negotiating in parliament, may yet be able to swing the second vice-president position. Under the current 2008 constitution, Daw Suu is not eligible to be nominated or selected for either post, but she has stated clearly that she will maintain a position “above the President” in leading the country, thus exercising both her leadership and accountability for the country’s future direction. She has also cautioned the elected NLD candidates not to hold any aspirations for executive (or cabinet) posts, and has instead emphasised her intent to have a “conciliation government” comprising a mix of ethnic stakeholders and technocrats. The NLD’s majority is thus seen to be more necessary in parliament for important legislative changes to be pushed through.

On the part of the USDP, several high-level candidates including President Thein Sein, have conceded defeat with grace. President Thein Sein has publicly assured a smooth handover. This has been echoed by the Commander-in-Chief, Senior General Min Aung Hlaing. Both met with Daw Suu in highly publicised meetings on 2 December. Daw Suu and her parliamentary colleague, Thura U Shwe Mann, had met in the immediate aftermath of the elections. The invitation to meet with all these principals was first extended by Daw Suu. In an unexpected move, Daw Suu also met with former SPDC supremo, Senior General Than Shwe, on 4 December in Naypyitaw, in a move apparently facilitated by Speaker of the House Thura U Shwe Mann, who maintains a good working relationship with Daw Suu. U Shwe Mann had been ousted from his position as acting chairman of the USDP in August 2015, giving rise to speculation about cracks in the USDP’s campaign strategy, and to his future role.

There are wide differences in how various segments of the populace view the 2015 general elections and their aftermath. The intellectuals – usually the best informed – are also the most critical, and there is some concern about a new elected team’s ability to govern. Still, the overall mood, which has been for “anything but the USDP”, fueled votes cast with hope for a better future. Macro-level reform measures by the USDP seems not to have touched the populace who has instead mainly felt the brunt of continuing electricity shortages and rising food prices. Thus, “change” presented a better option to most than continuity. The internal split in the USDP did not help matters. Yet, in the days preceding the election, the USDP camp displayed considerable confidence that they would do well in the polls.

MYANMAR’S POST-2015 FUTURE

Myanmar today remains a rather divided society on several key issues and concerns. The ethno-nationalist narrative is still strong, muzzling any voices speaking out on how the Rohingya issue is to be tackled. The conflation of this issue with religion resulted in no Muslim candidates being fielded by either of the large parties. This poses some concern for the space for religious minorities in the Buddhist-dominant society.

Congratulatory messages from the USDP leadership, including the President, to the NLD, and the conciliatory gesture by Daw Suu to the President, the Speaker and the Commander-in-Chief for dialogue on the country’s future, are good indicators that both the large parties are playing the game. In fact, an NLD-government would need to be even more inclusive and conciliatory than the USDP has ever been, as the constitutional odds are still stacked against too abrupt a change. The military has a say over who should be the home and defense ministers, and the unspoken understanding still remains not to cross any “red lines”. At this point though, what these red lines will be for the military (or the forces behind it) are still unclear.

Between now and the parliamentary session in early 2016 to elect the president and vice-presidents, it is important for the different principals in Myanmar’s political game to start discussing a practical modus vivendi. Already, moderate voices are cautioning that aspirations for “complete change” may not be realistic, and that pushing the envelope too far too soon may result in the military stepping in again. However, the military under Senior General Min Aung Hlaing seems reluctant to create another mess. Daw Suu realizes this, and thus very early on in the aftermath of the November 8 polls, called through her public exhortation to “lose nobly and win humbly”, for quiet celebrations and for her supporters not to insult the dignity of those who had lost.

As regards external relations, Daw Suu has reiterated continuity with the non-aligned foreign policy “that has been very successful… since independence”. Thus, Myanmar’s foreign policy looks likely to continue along the broad principles that motivated the initial opening and diversifying of external partnerships. Bilateral relations with neighbors such as China, Thailand, and to a certain extent India, will be important for Myanmar to balance, even as it continues to expand its role and participation in ASEAN. The normalization of relations with the United States may encourage the repeal of some of the sanctions enacted into federal law.

The 2015 elections are certainly not the be-all and end-all for Myanmar’s democratization and transformation. Institutions are still weak, as is capacity on the ground. The NLD can no doubt use the commitment of its supporters to help change mindsets. Thus, much depends on how the NLD’s conciliation government is conceptualized and negotiated. The Thein Sein administration had set the tone for more technocrats and experts to be part of the executive, and this looks likely to continue with the NLD’s commitment to have a representative mix of ethnic members and technocrats in its executive set-up. Ceasefire negotiations with the remaining eight insurgent groups may also require a continued role for the chief negotiator Aung Min (who lost his seat in the elections), as he had built personal relationships with the leaders of the insurgent groups when helming the negotiations for the Thein Sein government.

Going forward, the new government will have to continue with realities of the economy, relations with neighbours and partners, and civil-military relations. The “Rakhine issue” will not go away, and the NLD is aware that this requires delicate handling. However, there are many priorities for the new government to tackle.

Results of a first-ever poll undertaken by the FIDH, an international human rights NGO, on the human rights commitments of political parties in Myanmar, were released on 3 November in Yangon. Of the 19 participating political parties, 42 percent refused to respond to the issue of Muslim Rohingyas, and 74 percent indicated their disinclination to amend the 1982 Citizenship Law. Only 21 percent agreed that the next government should implement measures against discrimination and intolerance against religious minorities. However, some 63 percent thought that the next government should focus more on redress for land confiscation victims; 47 percent prioritized the release of all political prisoners; 36 percent called for a safe environment for the voluntary return of all refugees and internally displaced persons to their homes; and 31 percent emphasized the independence of the judiciary from the executive. These priorities are not mutually exclusive, though the results of this poll suggest that the political parties view these as issues that can be addressed independently of each other6.

Myanmar’s elections are arguably one of the most important political events in Southeast Asia in 2015. Already, the election results and their aftermath present potential consequences for Myanmar’s challenging triple transition that started in 2011. The new government will also be presented with continuing the tasks of 1) negotiating a lasting end to the decades-long internal conflicts; 2) entrenching democratic institutions and habits after decades of authoritarian rule; and 3) expanding the country’s regional role and reach. The following considerations also underpin the next steps in Myanmar’s journey towards change and democracy:

- The future role and status of the NLD as the ruling party.

- The different interest groups and factions seeking to influence Daw Suu. (Dealing with the military may be the least of her worries).

- Daw Suu still remains the most pivotal point of focus for national reconciliation. Yet, there are questions of “life after Daw Suu” for both the NLD and the country.

- National reconciliation covers more than the relationship between the military and the NLD. The many pressing internal issues to be tackled may yet turn Myanmar’s attention more inward-looking.

About the author:

* Moe Thuzar is Fellow at ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute.

Source:

This article was published by the ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute as ISEAS Perspective 70 (PDF).

Notes:

1 Kyaw Yin Hlaing (2008). “The State of the Pro-Democracy Movement in Authoritarian Burma/Myanmar”, Myanmar/Burma: Challenges and Perspectives, ed. Xiaolin Guo, Institute for Security and Development Policy: 2008. p. 99

2 Excerpted from Daw Suu’s interview with Dominic Faulder on 1 July 1989, which was published in the Asiaweek edition of 21 July 1989, and also included in “Freedom from Fear and Other Writings” (Penguin, UK: 1991) as Chapter 17, The People Want Freedom.

3 A statement issued by the National Democratic Front on 1 December 1995 supporting the NLD’s boycott of the constitution convention process and calling for dialogue, refers to letters from the NLD dated 28 November 1995 to the Chairman of the National Convention Convening Commission, stating its (NLD’s) decision not to participate in the National Convention.

4 The NLD contested 44 out of the 45 seats available.

5 The numbers do not include the military-held seats: 110 in the lower house, and 56 in the upper house. Without the military’s 25 percent, the seats up for grabs are 323 seats in the lower house and 168 seats in the upper house.

6 Full report on the poll findings at: https://www.fidh.org/en/region/asia/burma/political-parties-neglect- human-rights-priorities