Drawdown Of US Forces: A Decade Of Shifting Strategies In Afghanistan – Analysis

By Dr. Shanthie Mariet D Souza

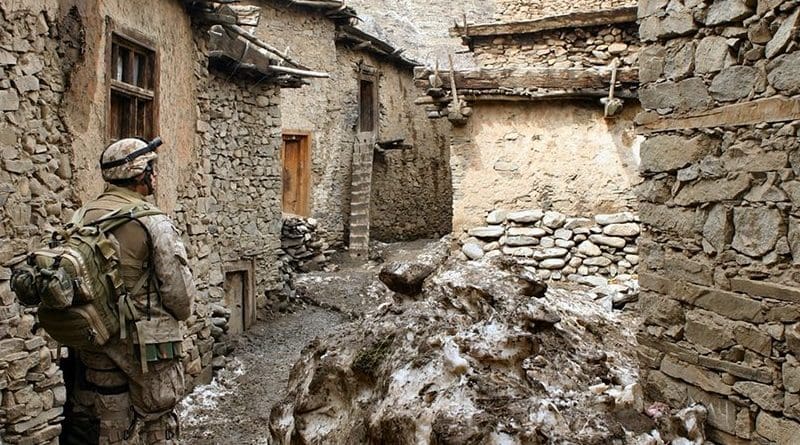

On July 13, 650 US troops left for home after completing their rotation in Afghanistan. These soldiers based in Kabul and the neighboring Parwan provinces would not be replaced. This marks the beginning of the drawdown of the US forces from the longest war.

A total of 10,000 US soldiers will be withdrawn in similar fashion this year and by the end of 2012, a total of 33,000 would have left Afghanistan. President Obama’s announcement of draw down of forces on June 22 is in line with his promise made on December 1, 2009, along with a troop surge to fight a “just war” in Afghanistan.

Next week, General David Petraeus, commander of the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF), too would bid goodbye to Afghanistan to head the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). Just like the 650 soldiers who preceded him, the general’s return too would resemble a retreat without having lived upto his July 2010 words. As he headed off to Kabul last year, General Petraeus, basking under the fame he got for having “stabilized” Iraq, had made a public statement “We are in this to win.”

Let alone securing a victory, Afghanistan under General Petraeus, with more military resource allocated than ever before, and having adopted a larger counter-insurgency strategy, slipped to be more dangerous and insurgency even more lethal and widespread.

General Petraeus had 140,000 multinational troops under his command, the biggest and best-equipped fighting machine ever fielded in NATO’s decade-long war. However, neither Iraq was stabilised in the true sense of the term, nor could Afghanistan be calmed.

What has plagued the decade long US policy is the lack of clarity in defining an “end-state” in Afghanistan. Thus, in absence of clear unified vision, strategies have vacillated between counter-terrorism and counter insurgency, with little effort to understand the realities and needs on the ground.

Available data shows that in the first six months of 2011, fatalities among the civilians hit a record high, registering an increase of 15 percent compared to the first half of 2010. Figures collated by the United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan (UNAMA) indicates that 1462 civilians were killed in roadside and suicide bombings, increased ground fighting and also air strikes by the coalition forces. The fact that 80 percent of these deaths were caused by the insurgents does not absolve the ISAF of its failure to dominate and win, the objectives identified by General Petraeus in 2010.

The inability to blunt the capacities of the insurgents, in the presence of sanctuary in the neighbouring country, has convinced the administration in the US and Kabul that a military victory against the insurgents is nearly impossible. Unless the insurgents are encouraged to be a part of the reconciliation process, Afghanistan would continue to remain unstable. President Obama wants to demonstrate success in Afghanistan for his re-election bid next year and is constrained by the rising unpopularity of the war and the fiscal restraints at home. In such a scenario, the search for “quick fix” could only intensify.

Even as the drawdown has begun, neither the reconciliation process has made any substantial progress, nor has the Afghan forces have shown any extraordinary signs of being able to take lead in the country’s security. With the weakening international troop presence and a growing resolve among the Taliban to carry on with its violent campaign, the prospects of long term stabilization in Afghanistan looks distant.

The Afghans are concerned that the gains made thus far would be lost. While Americans have avoided in getting embroiled in the nation-building efforts in Afghanistan, search for quick fix solutions like reliance on local powers, arming the tribal militia to form the Afghan Local Police and negotiated settlement with the Taliban could reverse the gains made thus far and further complicate the “transition.” The recent killing of Ahmed Wali Karzai indicates the limitations of reliance on such local power brokers.

The contours of the yet-to-be inked US-Afghan strategic partnership, which revolves around counter terrorism capability with limited troop presence will have to factor in political, governance and economic issues in the country, if the key objective of stabilization in Afghanistan is to be accomplished. Else, even the limited presence of “residual forces” to support the Afghans could come to resemble a ‘stale-mate’.

This article was published by Al Arabiya and is reprinted with the author’s permission