Military Intervention In Rio – OpEd

By COHA

By Alexandra Gale

Nearly one month after de facto President of Brazil Michel Temer issued an emergency decree that placed the Rio state police under control of the military, councilwoman Marielle Franco was killed under mysterious circumstances on the night of March 14.[i] Franco was a feminist activist who fought for black rights and was an outspoken critic of the military intervention in Rio and police brutality.[ii] Although no arrests have been made, the assassination appears to be a targeted silencing of a dissenting voice.

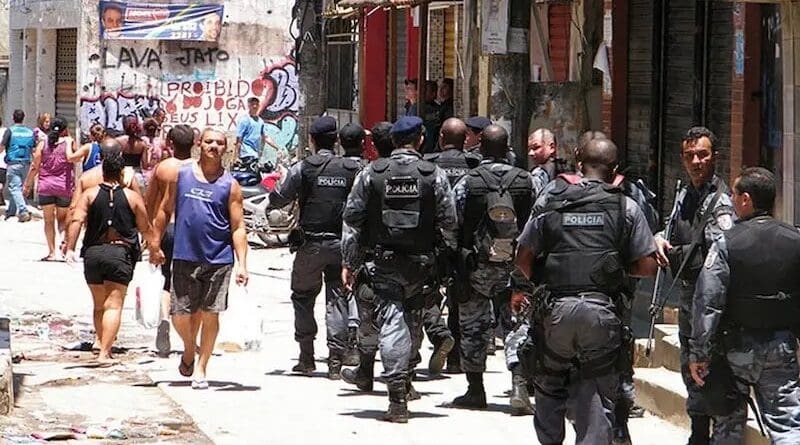

The military intervention currently underway in Rio de Janeiro was initiated on February 16, 2018 and effectively placed the state police force under the direct control of the armed forces. [iii] On February 23, a stark scene was presented when Brazilian military personnel approached residents on the streets of some of the poorest communities in the West Zone of Rio de Janeiro with a list of suspects in hand. Members of the military forces used their cellphones to photograph local residents holding their identification cards, and then forwarded the resulting photos to the Civil Police in order to check whether or not the residents had a criminal records. [iv] Army Colonel Carlos Frederico Cinelli stated that this unusual measure was not only legal but time-effective, ignoring that such “time-saving” efforts could result in the criminalization of entire communities whose inhabitants are almost always poor and non-white. [v] This invasive maneuver which documented citizens’ identification and image is just another harsh aspect of life under the new norm of increased military presence in Rio that many residents have had to submit to.

For the past two years, the state of Rio de Janeiro has been in the midst of a financial crisis which has exacerbated existing tensions and has contributed to a demonstrable increase in crime.[vi] The mostly unregulated shanty towns within as well as on the periphery of the city, neighborhoods commonly known as favelas, have historically operated with little government presence, which non-state actors have used to their own advantage.[vii] Despite multiple efforts by the police to “pacify” such communities, Rio currently hosts three major drug gangs and several paramilitary groups, who are fighting each other as well as against the police for territorial control. [viii] The situation has culminated into an explosion of urban violence over the past few years. In 2017 alone, there were 6,731 violent deaths in the state of Rio, or about 40 homicides per 100,000 citizens—the highest registered toll in eight years. [ix] Other crimes such as kidnapping, carjacking, and cell phones robberies have also increased.[x] Rio’s famed Carnaval celebrations, which this year attracted 1.5 million foreign tourists to the city, were marred by accounts of physical assault and robbery, footage of which was prominently displayed on daytime television. [xi] Of these homicide statistics, 77% of victims were black and a majority were young and black, a profile that is highly concentrated in the poor communities of Rio. [xii] Although the security crisis in Rio de Janeiro has gained the greatest degree of notoriety, the Brazilian states of Acre and Rio Grande do Norte currently have homicide rates almost twice as high as that of Rio de Janeiro. [xiii] The choice to involve the military in Rio instead of where the violence is more intense reveals a potentially politically motivated decision. Since polls have revealed that security is a top priority for Brazilians, a military intervention could be popular with many voters who support a tough-on-crime approach.[xiv] Although it appears that the decision to intervene solely in Rio may be politically motivated, other possible explanations include Rio’s economy, the importance of tourism, and Rio’s symbolic importance for the national image. [xv]

Temer’s February 16 decree gave the military broad authority in an attempt to restore law and order to Rio de Janeiro, placing the city police under the command of General Walter Souza Braga Netto.[xvi] The decree marks the first time since Brazil’s transition to democracy in 1985 that the government has used the constitutional provision that allows for the military to take control of the police force in special circumstances.[xvii] The presidential decree was passed by both houses of the Congress on February 20. [xviii] A common, if oversimplified narrative in Brazil is that the Rio police has effectively lost control of large areas of Rio due to a lack of adequate police resources and funding, which has allowed for the drug gangs to operate in the vacuum of authority.[xix] The poorer communities have been the most affected, and the military has set up checkpoints to search every person entering or exiting specific neighborhoods, while some communities have also been patrolled by armored vehicles and marine craft. [xx] Photos showing the military searching the backpacks of schoolchildren under the age of 10 have gone viral and have produced a considerable alarm among Brazilians who fear that the harsh treatment of poor black children reveals the military’s criminalization of their demographic. [xxi]

Although the military intervention has had the support among the right wing of the upper and middle classes, the lower class, which is most directly affected by the increased presence of the police in their neighborhoods, express doubt that the action will result in a significant decrease in crime. [xxii] The upper and middle-class Brazilians who support increased military presence live in the wealthier neighborhoods that already have less policing, and their support could stem from a desire to protect their personal property. The inhabitants of the poor communities are predominately black and more likely to suffer from indiscriminate police brutality than are other segments of the population.

In a February 27 interview with the British The Guardian, retired Army General Gilberto Pimentel expressed sympathy for the army’s dilemma in identifying who the criminals are, stating “we are going to operate in communities that are dominated by the bandits. It is very difficult to separate the good people from the bandits.” [xxiii] This statement is highly disconcerting and it reveals dangerous prejudices held by members of the military that are bound to contribute to the criminalization of entire communities, which can lead to human rights abuses and the death of innocents among a segment of the population.

Despite the lack of success of military intervention in Brazil’s recent past, Sergio Etchegoyen, a member of Temer’s cabinet, has stated that “Rio de Janeiro is a ‘laboratory’, implying if the military intervention in Rio is seen as a success by the military and the federal government, the military will feel emboldened to attempt a similar approach in other parts of the country. [xxiv]

The timing of the military intervention is suspicious to those who suspect that Temer, who has the approval of only approximately 5% of the population, is taking drastic action in an attempt increase his popularity or show strength leading up to the presidential election, which is scheduled for October of 2018. [xxv] Perhaps more importantly, during a period of military intervention enacted through the constitutional provision, lawmakers are prevented from making any major legislative changes. Thus, Temer’s proposed social security reform, which was highly unpopular, is provided with a ready-made excuse for its failure to pass. [xxvi]

For many Brazilians, the increased role of the military in Rio carries uncomfortable echoes of the military dictatorship, which ruled Brazil from 1964 to 1985. [xxvii] Under a new law passed in October of 2017, members of the armed forces who kill civilians can only be tried in the notoriously non-transparent military courts, a decision which could increase impunity for the military’s human rights abuses. [xxviii, xxix] Although the current political and economic crisis in Brazil may overshadow the unsettling news of the military intervention, it is evident that the current trend is of major concern for defenders of human rights and points to a wider trend of militarization of police, racism, and a lack of checks and balances in Brazilian politics and civic society.

*Alexandra Gale, Research Associate at the Council on Hemispheric Affairs

Additional editorial support provided by Aline Piva, Research Fellow, Liliana Muscarella, Extramural Research Fellow, and the Research Associates João Coimbra Sousa and Keith Carr at the Council on Hemispheric Affairs.