How Is Civil Society Doing In Libya? – Analysis

By INEGMA

By Marika Alpini

Since the civil uprising burst out in Benghazi in February 2011, a new Libyan civil society is trying to build from scratch its organizational structures, human capacities and programs, after 42 years of one of the most repressive and brutal regimes of the post-colonial era in North Africa. Much of the international attention has focused on how, in the past few months, civic groups, charities and social organizations, both of religious and secular inspiration, copiously flourished in a country where social activism had severely been repressed for decades.

In Gaddafi’s Libya, political parties had been officially banned, while the establishment of NGOs was allowed as long as they conformed to the goals of the revolution, i.e only charitable organizations were tolerated. Any type of association or organization of political, intellectual or controversial nature for the regime was punished with death. Professional associations embedded in the state structure and carefully monitored by the Revolutionary Committees, existed in place of independent student and labor unions.

Gaddafi himself labelled non-governmental organizations as “a bourgeois culture and an imitation of the West.” Before social activism strengthened by a new and powerful tool like social networks changed irreversibly the status quo in Middle East, his words seemed to echo the wide-spread conception about the impossibility of building an Arab civil society. The non-governmental sector was viewed as an element imported from – or exported by – the West, while the reasons and objectives behind a proactive civil society were widely perceived as incompatible with the social and political systems of the Arab world.

Development of Civil Society: The Arab Case

Many analysts have argued that the original function of civil society in the Western and Arab states differ in principle. While civil society has been considered the ‘watchdog’ of democracy and civil freedoms under modern Western liberal states, citizens of the modern Arab nations continued to maintain a stronger identification with their states and inspired leaders. While Western civil society started looking at the governments as a potential threat to liberal values, for Arab citizens, states and leaders primarily embodied the symbols of their anti-colonial struggle.

As a result, a vicious circle emerged. On the one hand, this lack of civil activism and state criticism contributed to the rise in power of autocratic and highly militarized regimes. On the other hand, the formation of a real democratic culture, on which civil society is based, has been obstructed. The anti-colonial struggle led by Moammar Gaddafi and the four-decade long authoritarian rule that followed seems to validate such theories. Secondly, it has been often pointed out that very strong tribal, familiar and religious ties, seen in many Arab societies as the only alternative to autocratic powers, consistently weakened Arab citizens’ civic sense and awareness of their role against state abuses. In Libya, for example, the importance of tribal and blood relations has retained its centrality, despite 42 years of centralized government.

At the moment, groups of more liberal orientation seem to gather mainly elites and returned exiles rather than focusing on gaining popular support. Currently, their view might not represent the majority but it cannot be disregarded that a more secular vision of future Libya has got a consistent representation within the National Transitional Council (NTC). Among them, the February 17th Coalition, formed by a prominent group of Libyan judges and lawyers, has been involved in the protests since their beginning and advocates for the separation of the political and religious sphere.

The Islamists of various stripes should not be counted out either. Although the influence and support to militant Salafist groups has certainly grown in North African countries, it makes sense to believe that more moderate views of political Islam, represented by the Muslim Brotherhood and the Senussi Sufis, will certainly retain a more central role in shaping the political life and the civil society of the new Libya. Through an extensive network of charitable and welfare activities, those groups, born as grassroots movements in the case of the Libyan Muslim Brotherhood, managed to gain popular support in a country affected by growing social disparities, international sanctions, economic mismanagement and a tyrannical authority. Their activism and organizational solidity seemed to have resisted effectively Gaddafi’s harsh repression and Islamist groups are now positioning themselves in the new political arenas of the country.

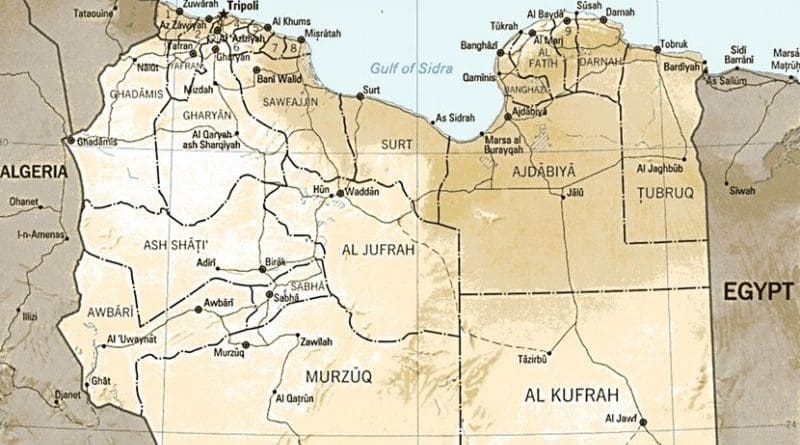

Finally, alongside these major clusters, there is an entire new rank of newly formed non-governmental organizations, many of them not registered yet, young activists, users of social media, bloggers and returned exiles, willing to give their contribution for the establishment of a Libyan civil society and an accountable, democratic government. For example, NGOs networks, workshops and training, supporting the capacity building of the non-governmental sector, have already been organized in Benghazi and other cities of Eastern Libya.

In fact, this latter fragment has constituted one of the newest and more active components of the non-governmental sector in the new Libya, withholding a major role in the anti-dictatorial uprising that sparked in many Arab countries. Although at the moment, the work of these Libyan NGOs focuses mainly on relief and humanitarian assistance for displaced persons, volunteerism, awareness of the importance of an active civil society and support to democratic institutions is not what these new Libyan civil activists seem to fall short of. The challenges they might face will lie instead in their ability to gain technical knowledge and human capacities, set programmatic strategies and secure adequate financial resources from international donors.

What is important to underline at this point, after presenting the main groups composing the new Libyan civil society, is that – with the exception of the most extremist fringes of the Salafi component – all together, secular and religious factions, liberal and more conservative blocs, are keen on rebranding the central role that a strong civil society will have in forming and preserving emerging democratic structures. This view, reiterated by the NTC in the document expressing the ‘Vision of a Democratic Libya,’ and these groups’ aspirations for an accountable and transparent government, respect of the rule of law, freedom of speech and association, perfectly fit in the objectives and values of the global civil society. It is also particularly significant to remind in the case of Libya that, before turning into a proper anti-government uprising, demonstrations initially sparked in Benghazi to demand the release of the lawyer and human rights activist Fathi Tarbel, who represented the families of over 1000 prisoners, allegedly killed by Libyan Security Forces in Abu Salim prison in 1996.

Possible Options of Foreign Assistance

However, inside and outside Libya there is general awareness that the outcome of the current strive of the Libyan civil society will extensively depend on the availability and consistency of external funding, mainly disbursed through “foreign aid” and the return of stolen, frozen assets. For example, it has been observed how the most important among non-Western donors, i.e the main oil-producing countries of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC), have been particularly proactive in funding relief and humanitarian interventions. Considerable financial resources have been poured in by Saudi Arabia, Kuwait and the UAE, more recently joined by Qatar, into other countries affected by natural disasters, difficult economic conditions and conflicts. Charitable Islamic principles are certainly animating international donations and there is an intense widening of aid packages occurring throughout the region from the Gulf.

However, Arab foreign aid, dispensed both through bilateral and multilateral channels and agencies, has shifted since the beginning of the 1990s from the form of grants to the form of loans. It has been also complemented by agreements, aimed at fostering donors’ economic activities, investments or exports. Zakat (pure charity) is helpful and the way “oil” foreign aid is being disbursed by GCC nations, and follows the patterns and objectives of Western nations and involves loans, interest rates, and commercial agreements with the recipient nations.

It is not too hard to believe that in the case of Libya, Arab foreign aid, to the same extent of its Western counterpart, will also aim at expanding donors’ influence on a country offering great political and economic interests. Italian donations and non-governmental organizations, for example, have poured into Libya since the beginning of the crisis. Italy is clearly interested in maintaining its strong links to Libya and not only in light of its colonial past. Bilateral economic and political ties between the two countries have intensified in the past ten years and covered sectors such as agreements on illegal immigration flows, mutual investment channels as well as exploitation of the abundant crude resources. Britain and France, as well as the United States, are also lining up with substantial packages.

To the same extent, Arab donors are very motivated to regain their influence on an Arab OPEC member, which presents considerable strategic importance and abundant natural resources. GCC benefactors are aware that in the past twenty-years, Libya has progressively distanced itself from the rest of the Arab nations, with Gaddafi being isolated from all the Arab leaders. This, finally, brought the Libyan leader to turn to other non-Arab African nations for alliances and support in the last decade. This entire tide is now been reversed. Secondly, Arab donors have generally been seen as less interfering than Western powers in the domestic dimension of aid recipients. Conditionalities, encouraging economic and political reforms in the assisted countries are mainly associated to Western funding. Yet, as Arab foreign aid is by now mainly provided in form of loans, generally calling for guarantees, there are aspects such as fight against corruption, transparency and efficient tendering that will set the agenda regarding domestic reforms and politics, even when the assistance comes from Arab nations.

All in all, it is true that the major Arab donors are less intrusive in the political reforms of the recipient states, but their assistance cannot certainly be seen as ‘neutral’. It is for example clear that their funding, especially when coming from Saudi Arabia, aims primarily at spreading and strengthening in the society’s adherence to Islamic values and behavior. It is therefore clear which political component of the current Libyan civil society will benefit from these funds and which ones will be disadvantaged. It is also likely that the non-Islamist, secular part will continue relying on Western financial and technical assistance in order to survive.

Conclusion

While the latest events showed that an Arab civil society has formed and is particularly active, in Libya, motivation, activism and volunteerism do not seem to be lacking. Rather, the main challenges civil society will face are likely to concern the acquisition of technical knowledge, human capacities and programmatic strategies. Foreign funding will also have a central role in determining the development of the Libyan civil society and non-governmental sector.

Before 2011, some would claim that mainly Arab assistance is needed for the creation of a truly Arab civil society and containment of neo-colonial attempts. Yet, this stance overlooks important aspects, including the fact that the main Arab donors, namely the oil-rich Gulf states, while undeniably animated by Islamic charitable principles, have also proved to be moved by national interests. In addition, despite some recent improvements, the major Arab donor countries present weak records in terms of democratic standards, transparency of funding, and empowerment of the civil society at home. This creates many doubts on how they will be able to provide Libyan civil society with technical expertise and democratic support. Finally, their aid channels are very likely to uphold solely the Islamist component of the forming Libyan civil society, therefore creating risky imbalances with the secular fractions and undermining the creation of sustainable democratic structure. Now in the aftermath of the Arab Spring and the revolt’s ongoing wave across the region, Arab NGO assistance will likely change and reverse many of the negative assessments of the recent past.

Finally, Western civil society assistance and funding will continue holding an essential role in supporting the formation of the non-governmental sector in Libya. Western donors, undeniably moved also by political and economic interests, will be involved in building the capacities and maintaining a more participatory approach of the Libyan third sector. Adherence to international standards, inclusive representation of the secular and religious components and diversified sources of funding will possibly represent the crucial variables, determining the short and long term developments of the thriving civil society in Libya.

Marika Alpini, Non-Resident Analyst, INEGMA