Why India-Pakistan Dialogue Needs To Be Reconceptualised Alongn Lines Of ‘Principled Negotiations’ – Analysis

By Institute of South Asian Studies

By Subrata Kumar Mitra*

Comments in the press on the cancelled trip of Mr Sartaj Aziz, Special Advisor to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs Pakistan, to Delhi to meet his Indian counterpart vary between a ‘missed opportunity’, a ‘farce’ and a plaidoyer for a new beginning.2 The cautious optimism that marked the three weeks that intervened between the Ufa initiative and the trip that failed to materialise gives ground to believe that serious analysts had seen some probability of progress of India-Pakistan dialogue in this initiative. However, a critical analysis of the discourse that surrounded the cancelled trip of Mr Sartaz Aziz reveals the structural hurdles that underpin any meaningful dialogue between India and Pakistan as things stand.

I argue in this essay that the failure of the Ufa initiative to follow its course is an alert call for deeper analysis and strategising – a warning that India and Pakistan can ignore only at enormous and avoidable costs.3 However, while there is a general admission of the need for India and Pakistan to break out of the ‘stalemate’4 in which they find themselves, there is no radically new thinking on how this can be done. In suggesting a move towards ‘principled negotiations’,5 this article points towards some concrete steps that might contribute to the breaking of the stalemated, low-level-equilibrium- trap in which the two hostile neighbours find themselves at this moment.

The Ufa ‘Agreement’ and its Aftermath

The meeting of Mr Aziz with Mr Ajit Doval, National Security Advisors (NSAs) was agreed to at Ufa, Russia, on 10 July 2015 where India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Pakistan’s Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif, had agreed to the following five points on the side-lines of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation summit. As reported in the press, five points were agreed to.6

- A meeting in New Delhi between the two NSAs to discuss all issues connected to terrorism.

- Early meetings of DG BSF and DG Pakistani Rangers followed by the DGMOs.

- Decision for the release of fishermen in each other’s custody, along with their boats, within a period of 15 days.

- Mechanisms for facilitating religious tourism.

- Both sides agreed to discuss ways and means to expedite the Mumbai case

trial, including additional information like providing voice samples.

Following the meeting in Ufa, Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif came in for vigorous criticism at home on account of the first and the fifth points where he was seen to have conceded too much to India by having failed to include Kashmir among the issues to be discussed.7 The events that unfolded leading the acrimonious cancellation of the visit could have been easily anticipated. The fact that events unfolded differently from the predicted direction shows the limited utility of the thinking that currently dominates the Indian position in terms of its capacity to initiate and sustain a serious dialogue with Pakistan. For India and Mr Modi, the event has acquired a serious significance. Rather than merely a tactical failure, this is the second major setback for Mr Modi’s larger foreign policy framework regarding Pakistan, following the first one marked by India’s cancellation of the Foreign Secretaries’ meeting between India and Pakistan. As long night on Sunday (23 August, 2015) unfolded, Pakistan managed to focus global attention, once again on the Kashmir conflict and not terrorism – precisely what India wanted to avoid.

During the three ominous weeks that Pakistan took to set a date for the visit of Mr Sartaz Aziz, the interpretations of the Ufa initiative and expectations arising out of them grew in radically divergent directions in India and Pakistan. Though the two PMs agreed to the NSAs meeting, there were some public disagreements about the agendas of the meeting almost immediately after the surprise announcement at Ufa. However, the speed with which the divergent interpretations of what was exactly agreed to surfaced, reveals the chasm that separates the positions of the two countries. India insists that the agreement was made to discuss terrorism; Pakistan does not see it that way and wishes to broaden the discussion and bring in the Kashmir issue. As the Indian side saw it, the intent behind Mr Sartaz Aziz’s insistence on meeting the Hurriyat,8 though it was presented only as a symbolic meeting in a large get-together at the Pakistan High Commission in Delhi, was to broaden the agreed agenda and bring the Kashmir question back in again.

Had the meeting taken place, this would have been the first formal high-level meeting between the two countries after the cancellation of the two foreign secretaries meeting in 2014. There are striking parallels between the two failures – the two foreign secretaries in 2014 and the two NSAs now. In each case India has tried to focus on the specific issue of cross-border terrorism in a bilateral setting whereas Pakistan has sought to broaden the issue and give the ‘dialogue’ a tripartite character by including Kashmir and the Hurriyat, against which India has vigorously protested. The Indian case for focussing only on terrorism and wanting a quick resolution of the connected issues (case of perpetrators of Mumbai attack, Dawood Ibrahim, Zaki ur Rehman Lakhvi, training camps in Pakistan-occupied Kashmir in which terrorists are launched into India) follow from the basic premise of Kashmir’s accession to India as final and binding, and assumptions that underpin the Indian position.

Contrasting Position of India and Pakistan on Kashmir

In order to understand the divergent interpretations of the follow-up to the Ufa initiative, we have to look at India and Pakistan separately. In India, one needs to go back to the election campaigns of Mr Modi, who promised to ‘erase the menace of terrorism’ without necessarily committing himself to any particular solution to the Kashmir conflict. Indian thinking is based is based on a framework that has the following six assumptions:

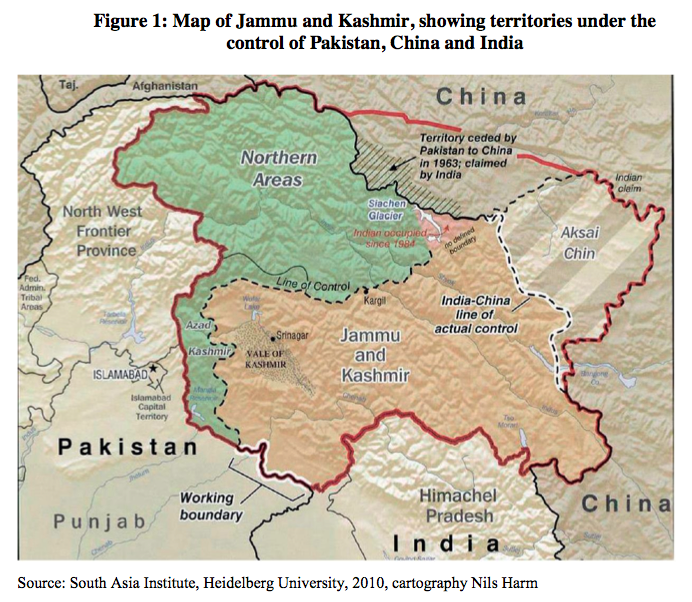

- The integration of Jammu and Kashmir with the Indian Union is legal and final. As such, the parts of Jammu and Kashmir that are under the occupation of Pakistan and China are illegal. This also includes the parts of Jammu and Kashmir ceded to China by the Pakistan-China agreement of 1963. (See map, below).

- The legitimacy of this position is supported by an all-party resolution of the Indian Parliament in 1994. (See box 1, below).

- The fact that regular, fair and free elections have taken place in Kashmir subsumes the need for a plebiscite in Jammu and Kashmir.

- A plebiscite could have taken place only on the condition that Pakistan first vacated the occupied territories (Azad Kashmir) which has not happened. Besides, in the hypothetical event of a plebiscite, the only choice would be between Kashmir joining either India or Pakistan. In other words, the independence of Kashmir could not be an option.

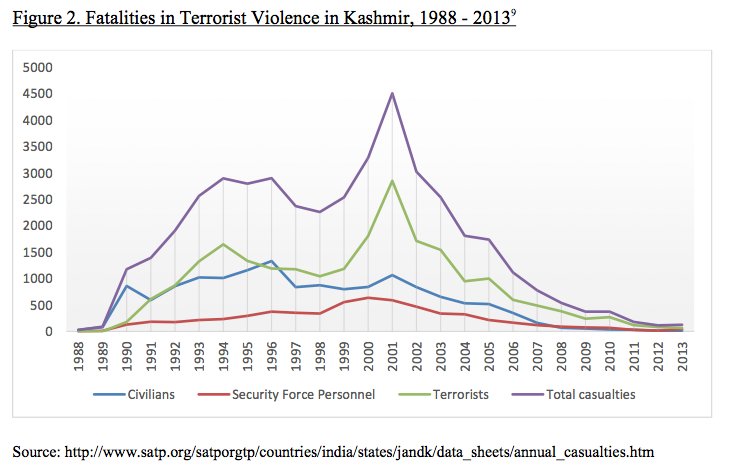

- Strong law and order management could produce a stable border and give a permanent character to the Line of Control that marks the position of ceasefire in the original 1947-48 war between the two neighbours which is still under the observation of the representatives of the United Nations. (See Figure 2 ).

- Muslim-majority Kashmir’s integration with India is an important argument of India’s character as a secular state which does not consider religion to be the basis of state formation.

Figure 1: Map of Jammu and Kashmir, showing territories under the control of Pakistan, China and India

In response to increasing terrorist violence and Pakistan’s attempt to highlight the Kashmir dispute internationally, both Houses of the Indian Parliament unanimously passed a resolution on 22 February 1994 on Jammu and Kashmir. (See Box 1, below). This landmark resolution of the Parliament put on record the assertion that the State of Jammu and Kashmir was an “integral part of India” and that Pakistan must vacate parts of the State under its occupation. A close reading of the resolution helps unpack all the assumptions of India that underpin the Indian position.

Box 1: Parliament Resolution on Jammu and Kashmir

“This House note with deep concern Pakistan’s role in imparting training to the terrorists in camps located in Pakistan and Pakistan Occupied Kashmir, the supply of weapons and funds, assistance in infiltration of trained militants, including foreign mercenaries into Jammu and Kashmir with the avowed purpose of creating disorder, disharmony and subversion:

- reiterates that the militants trained in Pakistan are indulging in murder, loot and other heinous crimes against the people, taking them hostage and creating an atmosphere of terror;

- Condemns strongly the continued support and encouragement Pakistan is extending to subversive and terrorist activities in the Indian state of Jammu & Kashmir;

- Calls upon Pakistan to stop forthwith its support to terrorism, which is in violation of the Simla Agreement and the internationally accepted norms of inter-State conduct and is the root cause of tension between the two countries reiterates that the Indian political and democratic structures and the Constitution provide for firm guarantees for the promotion and protection of human rights of all its citizens;

- Regard Pakistan’s anti-India campaign of calumny and falsehood as unacceptable and deplorable.

- Notes with deep concern the highly provocative statements emanating from Pakistan urges Pakistan to refrain from making statements which vitiate the atmosphere and incite public opinion;

Expresses regret and concern at the pitiable conditions and violations of human rights and denial of democratic freedoms of the people in those areas of the Indian State of Jammu and Kashmir, which are under the illegal occupation of Pakistan; On behalf of the People of India, firmly declares that:

(a) The State of Jammu & Kashmir has been, is and shall be an integral part of India and any attempts to separate it from the rest of the country will be resisted by all necessary means;

(b) India has the will and capacity to firmly counter all designs against its unity, sovereignty and territorial integrity;

and demands that –

(c) Pakistan must vacate the areas of the Indian State of Jammu and Kashmir, which they have occupied through aggression; and resolves that –

(d) All attempts to interfere in the internal affairs of India will be met resolutely.”

The Resolution was unanimously adopted. Mr. Speaker: The Resolution is unanimously passed.February 22, 1994

http://www.kashmir-information.com/LegalDocs/ParliamentRes.html.

The assumptions that underpin the Pakistani position contest some of the assumptions of India and add some additional ones for extra effect:

- India’s claim of the eternal union of Kashmir with the Indian republic is legally unfounded (no copy of the original Instrument of Accession is available); (King Hari Singh was coerced by the Indian government to sign the Instrument of Accession.

- The legitimacy of the integration of Kashmir is questioned by the mass uprising (parallel to the Ittifada in Palestine), and a plebiscite will confirm it.

- World opinion supports the Pakistani position on Kashmir

- Pakistan has the solid support of China in terms of its Kashmir position.

- Opinion of Islamic countries supports the integration of Muslim majority

Kashmir with Pakistan, carved out of British India as a homeland for Muslims

of South Asia. - Continuous pressure on India through the mobilisation of opinion in global

fora, lobbying Washington, cross-border terrorism, overt and covert links with Muslim organisations in India will one day either destabilise India or will make the cost of keeping Kashmir in India too high for the Indian state.

The two sets of assumptions specified above constitute the two hard, contrasting positions whose hiatus scuttles specific initiatives like Ufa, and, left intact, might contribute to the cancellation of the planned visit Prime Minister Modi to Pakistan in 2016.

The coming of Mr Modi to the centre stage of Indian politics as Prime Minister has added an extra élan to the Indian position as the core of India’s Pakistan policy. Under him, Indian border forces and the military have been given more of a free hand in taking actions against terrorists’ activities and ceasefire violations from Pakistan. The BJP, Mr Modi’s party which, for the first time in the past thirty years has emerged as the single majority party in the Lok Sabha, is the junior partner of the People’s Democratic Party (PDP), in the coalition government of Kashmir. Any association of the Hurriyat which has chosen to stay out of electoral democracy in a talk that might involve the future of Kashmir would fundamentally question the legitimacy of the Kashmir polls, besides being unacceptable to the full spectrum of India’s political establishment, the bureaucracy and the army. (See box 1, again).

For Pakistan, that every opportunity at a dialogue with India is used to broaden the issue and bring Kashmir in, is equally understandable. As the Pakistani argument goes, Kashmir conflict is a continuation of the unresolved issue of the partition of India. As already mentioned above, Pakistan trenchantly contests the instrument of accession through which the then King of Kashmir Maharaja Hari Singh agreed to join Jammu & Kashmir with India. Pakistan has long advocated a plebiscite to decide the issue of Kashmir accession as commanded by the UN Security Council Resolution 47 (Resolution of 21 April 1948). In the light of this constellation of factors, the planned meeting of Mr Aziz with the Hurriyat leaders was seen in Delhi merely as the customary Pakistani strategy to keep the pot boiling, and to internationalise the issue.

Implications of the Low-Level-Equilibrium-Trap in Kashmir for India and Pakistan

An analysis of trends in violent incidents in Kashmir will give an insight into the military and political prognosis of India and Pakistan. Thanks to vast improvements in the deployment of the army, paramilitary and police forces and better coordination of civil and military intelligence, violence in Kashmir has declined quite radically. (See Figure 2, again) The downward sloping curves create an impression of a firm, linear decrease in violence that the Indian army believes will eventually see the problem disappear on its own. Such an assumption, which becomes a contributory cause to escalation for reasons underpinning the Pakistani position, is dangerous and could close the window of opportunity for a legitimate and enduring solution to the conflict in Kashmir. Let us note that while the curves all point downwards after the peak year of 2001, rather than falling to zero, they have become asymptotic. (See figure 2, again)

In terms of logistics and strategy, Indian army reads this data as a success of law and order management, border fencing and the Armed Forces (Special Powers) Act which gives special powers of search and arrest to the army. However, while the rate of casualties has definitely come down, the quest for a stable, democratic regime in Kashmir, based on law and order and free of military presence like most parts of India (with the exception of the North-East), is far from over. The combination of a sullen population and the ability of cross-border terrorists to stage spectacular attacks show that despite radical reduction in casualties the conflict in Kashmir has reached a stalemate. Politics in Kashmir stays locked into a ‘low-level-equilibrium-trap’ where India cannot quite manage to ‘win’ decisively. Forces opposed to the continuation of Jammu and Kashmir in the Indian Union include cross-border terrorist organisations as well as those drawing support from within India, with links to rogue elements of the Pakistani army, and sections of the Hurriyat who want independence of Kashmir. They do not constitute a cohesive group, which would be able to mobilise itself as a united front, make a decisive strike and break the deadlock.

The conventional approach leads to a suboptimal outcome for both India and Pakistan

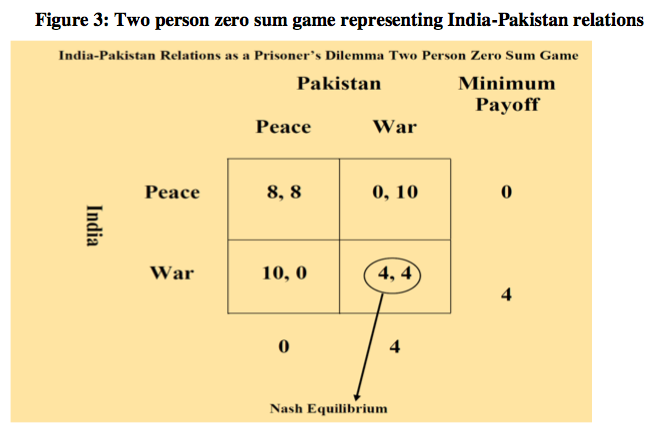

In order to see the dynamics that underpins the deadlock in India-Pakistan consider the following simulation, presented in the form of a two-person zero-sum game (Figure 3). Each of the two parties to this ‘game’, in this case, India and Pakistan, has a choice of being peace-like (opening-up for trade, cutting down on militarisation) or war-like (closing down trade and investing in enhancing military strength). The payoffs to each are presented in the cells, where the first figure represents the expected gain of the player on the left (in this case India) and the second number corresponds to the expected game of the player named on the top (in this case, Pakistan).

For the sake of simplicity, we have adopted metric scales for the pay-offs.10 Thus, when India opts for peace and Pakistan reciprocates, India can expect to gain 8 points (and India can anticipate Pakistan also to cash the ‘peace dividend’). When both opt for war, the gains get reduced, to 4 for India (and for Pakistan as well).11 However, in the event India opts for peace and Pakistan chooses the war option, it can deal a fatal blow, to sever Kashmir from India (which is what Pakistan had indeed attempted in 1965 and later, in 1999 Kargil war). In this case, Pakistan can expect 10 points as against India’s 0. The symmetric opposite would be the case if Pakistan opted for peace and India went for the war option. The Indo-Pak war of 1971 where India could capitalise on Pakistan’s logistical difficulties and split the country would illustrate the determination of Pakistan not to let off guard – an argument which helps understand the determination of Pakistan to stay ahead of India with regard to nuclear weapons – regardless of the cost.

In a two-person game, each player chooses his options unilaterally, based on the calculation of the likely minimum payoff from each tactic. So, seen through the eyes of India the peace option carries the potential of a payoff of 0, whereas the war option could yield either 10 or t4, and in any case, a minimum of 4. Given a choice between 0 and 4, a rational player could be expected to choose 4, i.e. the war option. The same logic holds for Pakistan too. So, the likely outcome of this game would be the simultaneous choice of war-war, yielding the suboptimal gain of 4 whereas 8 could have been possible. In the language of game theory this is a strong and stable outcome, known as Nash equilibrium. To see why that might be the case, imagine India being tempted by the peace dividend and opting for peace. If Pakistan is sure that Indians would lower their guard, one can expect them to go for the war option and deal the fatal blow. (Those familiar with the rapidity with which the Pakistani army mobilised troops on Kargil heights following Vajpayee’s ‘bus diplomacy’ would understand the logic of the game.

The Indian position on Pakistan corresponds to the lesson that we learn from the above example. India counts on the continuation of the military status quo though it is suboptimal, and hopes that the functioning of a regional government, and directly elected local panchayats, schools, colleges and hospitals would produce a semblance of normalcy which the world would eventually recognise as permanent. That calculation itself reinforces the desire on the opposite side to keep the pressure on, looking for loopholes where to strike and mobilise world opinion against the attempts of a powerful neighbour using its superior force to coerce the weaker party to accept what it considers illegitimate.

The two-person zero-sum game depicted above also resembles US-USSR relations at the height of the Cold War. For two rational players – here rationality is understood as the ability to maximise expected gain – a “mutually hurting stalemate” can eventually lead to cooperation in the form of a “mutually satisfying agreement” in which “divergent positions are combined into a single outcome”.12 One can thus understand why couples caught in bitter protracted divorce cases sometimes opt for an out-of- court settlement; why in the trench warfare of the First World War the enemies – the Anglo-French army on one side and the Germans on the other – could implicitly collude;13 and how the Strategic Arms Limitation Treaty (SALT) could take place despite the Cold War rivalry between the United States and the Soviet Union.

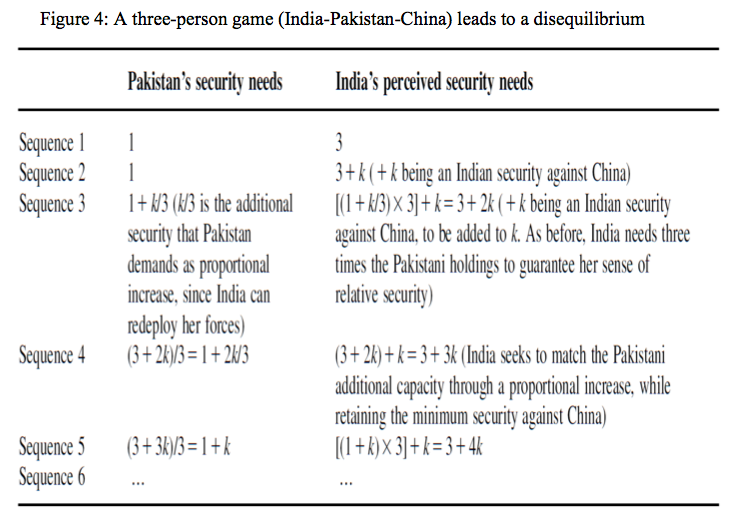

However, such is not the case with India and Pakistan. To understand why this is not the case, one has to put the two countries in context. Thus, one can see that the two- person game is actually a part of a three-person game, for China is part of this triangular relationship. The presence of China would cause the low-level-equilibrium- trap to dissolve into a series of unstable outcomes, constantly egging India and Pakistan into a spiral of bitter rivalry and arms race.

To see this consider the situation depicted in figure 4 (below). In the first sequence, India and Pakistan have worked out a ratio of arms (eg 3:1), a form of balance of power, whereby Pakistan has a proportionate counter-threat to the Indian threat. However, India might argue that India also needs to balance against China and therefore would need k units of force to supplement its stock pile. (Sequence 2) At this point, Pakistan can argue that it would need to have one-third of everything India has (“where is the guarantee that India would not turn the supplementary force against Pakistan in order to deal the fatal blow?” Pakistan might argue). So, in Sequence 3 one has a situation where Pakistan’s security need is satisfied, but this might make India insecure and act as an incentive for another round of arms acquisition by the country. This would start the kind of arms race between the two that somewhat resembles the situation obtaining today.

The way out of this dangerous spiral where intense political violence lurks just under the surface of a deceptive peace, lies in the realm of ‘principled negotiation’ (Fisher et al 1991). The need for taking stock of Kashmir is particularly urgent in the present context because the reduction of militancy compared to the recent past can lead to complacency14 and the very window of opportunity that has opened up with the reduction of militancy might shut, if a major effort for an enduring solution is not taken as a matter of priority.

The ‘Principled Negotiation’ Model for a Durable Conflict Regulation

Since a stable and effective negotiated agreement among adversaries is a crucial component of the model, it is important to analyse the components of what is known as ‘principled’ negotiation. It is a method developed by Fisher, Ury and Patton (1981, subsequently published in 1991, 2011) which offers some norms of negotiation that are designed to facilitate the parties to a conflict to reach an amicable accord. According to them the four basic points (people, interests, options, the criteria of acceptability of the solution to the stakeholders) define a straightforward method of negotiating that they claim can be used under any circumstances. ‘Principled’ negotiation requires the separation of people from issues; focusing on interests and not on positions; inventing new options for mutual gain and insisting on objective criteria in choosing options. The main hypothesis that follows from these assumptions is that negotiations that follow these four points have a greater chance of reaching a successful and lasting outcome than those which do not take these into account. Moreover, principled negotiators know their ‘best alternative to a negotiated agreement’ (BATNA). The model suggests that an enduring deal can be struck when both (all) parties see the agreement as in their interest (in terms of the costs and benefits relative to the next best outcome).

Getting to ‘Principled Negotiation’ Without ‘Giving In’

I have shown elsewhere that left to themselves India and Pakistan will not converge to a stable equilibrium in terms of peaceful relations on the lines of post-war France and Germany or the United States and the USSR on the lines of the SALT15 talks that finally ended the Cold War.16 Nor is the cost of the low-level-equilibrium trap likely to lead the adversaries towards negotiation the way a ‘mutually hurting stalemate’17 does for those whose interests are hurt; (border populations, for example) are not the ones who have the voice, and those who have the power to decide are way beyond the firing line!

Kashmir conflict is caught in a ‘low level equilibrium trap’ –a state of no-war, no- peace – where heavy (but unsustainable) military presence confronts a state of low militancy. The parties to the conflict build their strategies on the assumption that any sign of weakening by the Indian state can trigger renewed bouts of violence. The consequence is a stalemate where the messy status quo prevails faute de mieux because solutions which look neat on paper have no takers and little chance of being implemented in reality.

Why has India resolutely refused to accept the singularity of the Kashmir conflict as compared to other sub-national movements of India? The enduring character of the Kashmir conflict, the oldest of its kind in India, and perhaps, one of the most durable in the world, is puzzling in view of India’s relative success with ethno-national movements that have staked their claims to an exclusive homeland, and have found a niche within the Indian federation. An analysis of the parameters of the Kashmir conflict shows why the conventional Indian model of coping, based on the negotiated accommodation of sub-national movements through a strategic combination of force, power-sharing and federalization has only been partially successful in Kashmir and, offers some radical steps towards a solution that might be more acceptable to all the stakeholders.

The conventional ‘Indian’ model has not been as successful in integrating Kashmir within the democratic political system of India. This is not because of the essential difference of Kashmir from the rest of India but because of some additional parameters that affect the functioning of the conventional model. The fragmentation of the rebels and the exogenous factors are among the additional considerations that have reduced the efficacy of the ‘Indian model’ in terms of coping with sub- nationalism.

Beyond the Conventional Indian Strategy: Why a New Approach to Negotiating Kashmir is called for

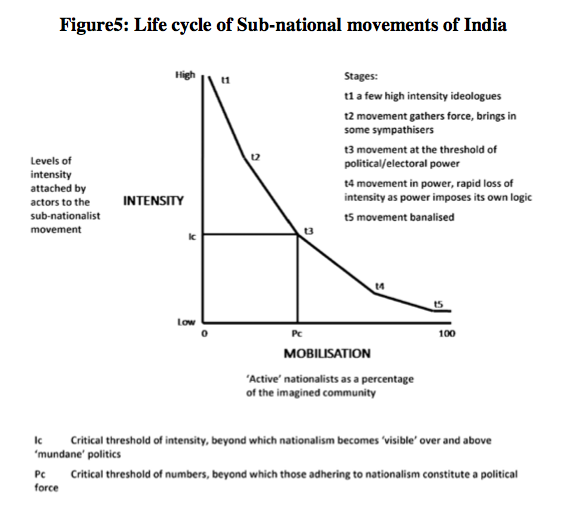

Since India’s Kashmir strategy envisages the conflict as a sub-national movement which typically combines force and participation, it is important to discuss the components of the Indian model. As India perceives it, most ethno-nationalist movements attract media attention when they first appear with their customary fury, mass insurgency and military action, but eventually they find an institutional solution within the Indian political system. And though continued political unrest in Kashmir continues to challenge this thesis, the case of Punjab in the 1990s and Tamil Nadu in the 1960s, both of which, after a spate of political turbulence, have settled down to normal parliamentary politics, illustrate this mode of successful conflict resolution in India.

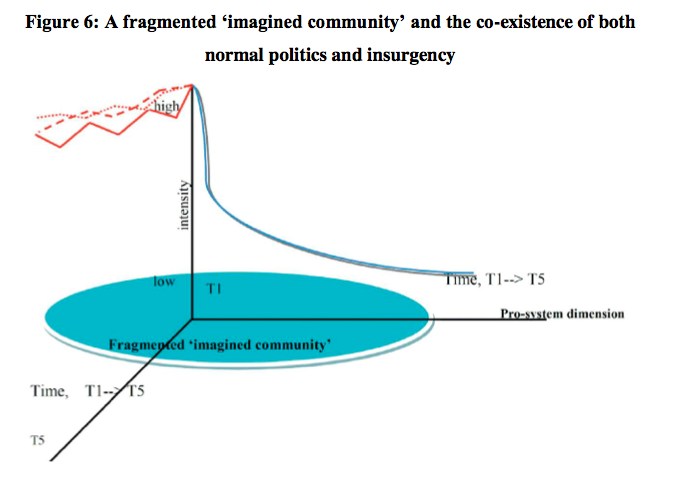

The typical sub-national movement (Figure 5) begins with a few advocates, fired up with the zeal of a separate state and willing to risk all. Their high intensity is juxtaposed with the paucity of their numbers. However, when the issue of a separate state acquires a firm empirical anchor in social, political and economic cleavages, the number of adherents grows and average intensity comes down. (Time t2) If the trend continues, a point comes when the movement acquires a mass character and enters elections. Once successful, the leaders of the movement form the government of a new political unit which corresponds to the territorial base of the imagined community.18

The deceptive similarity of Kashmir to other ethno-national movements19 has caused India’s strategic analysts to approach the region with the same tool kit of a combination of force and persuasion but within the framework of the Indian Constitution. In Kashmir, the multiplicity of actors, their overlapping, exclusive and entangled agendas, as well as different BATNAs, necessitate a multi-dimensional, multi-level model of solution that is radically different from what convention dictates. The Indian model does not pay sufficient heed to the singularity of Kashmir which, in terms of cross-border entanglements, resembles the separatist movements in the North East. In the light of the analytical issues that Kashmir gives rise to, one needs to reconsider the main premises of the model, expand its domain by including new variables, and reconsider previous evidence, leading to a reformulation of the conventional model (See figure 6).20

The political field in Kashmir is structured along two different dimensions that correspond, respectively, to the transactional politics within parliamentary and democratic institutions, and to a radical, separatist dimension. Part of the political community perceives its stake as firmly anchored in transactional politics of elections, lobbying, patronage, office and professional careers. There is another section, which is numerically smaller but whose intensity continues to be high. They are sustained by both local support and extra-territorial flow of money, personnel, ideological tools, weapons and training. There is considerable fragmentation within each of the two segments; as such, for the Indian state, there is no leading contender among the separatists with whom to negotiate.

Broadening the agenda and turning rebels and adversaries into stakeholders and partners through the ‘Composite Dialogue’

Any enduring solution to the Kashmir conflict must meet two necessary conditions. First, it must ensure a method whereby rebels and adversaries can become stakeholders; secondly, the solution must have the backing of the primary stake- holders, namely India, Pakistan and China, whose security interests should be part of the negotiation.

As the strongest military and political presence in Jammu and Kashmir, India is best placed to initiate the process of multi-level negotiation.21 This can be initiated by a joint agreement of India, Pakistan and China to transform the reality on the ground to a legal fact. The transformation of the de facto lines of control to de jure frontiers22 will send a strong signal to political forces active within the three parts of Jammu and Kashmir, respectively under the control of India, Pakistan and China to think of the best solution they can come up with for their own governance. Here again, India is well-placed to continue what India does best, i.e., to continue the consolidation of democratic participation (regular panchayat elections in Kashmir are a case in point); and encourage the democratically-elected government in Kashmir to integrate the Kashmiri market with the thriving Indian market properly by removing the restrictions on immovable property ownership by non-Kashmiris.23 Instead of being withdrawn, the army should be redeployed to protect the frontiers; policing should be done by Kashmiri police. Special travel documents should be provided to residents of Jammu and Kashmir for cross-border travel. Finally, India, Pakistan and China should work towards a CBM to set up a joint front against terrorism.24

The steps outlined above form part of the method of principled negotiation, suitably adapted to a multi-level context. They can be used to simulate the multi-level negotiation one can imagine taking place between, for example, India and Pakistan currently on water, terrorism, Kashmir, drugs and trade. Thus, despite massive military presence on both sides of the border in Kashmir, efforts are being made through the ‘composite dialogue’25 to move towards ‘principled’ negotiations based on interests (for example negotiations on economic issues such as water sharing and quadrupling of trade volume) and innovative solutions (border-crossing is made easier by means of bus service from Srinagar to Lahore) as well as separation of people from problems (for both India and Pakistan terrorism represents a mutual problem, a problem that the countries try to tackle together). The sooner the actors, empowered as stakeholders, realise the true nature of what is at stake and make credible bids, the easier it would be to reach enduring solutions to conflicts that appear intractable. This would require the Indian public to be ready to engage in a ‘land for peace’ deal – not the easiest thing to do in a democracy as one knows only too well from the comparable case of Israel and the ‘occupied territories’ in the enduring Middle-East conflict. The recent initiative to solve the issue of enclaves along the India- Bangladesh frontier shows that the combination of political will and effective leadership can solve long-standing issues that were once considered insurmountable.

India should have learnt by now that the stance of injured innocence did not do much good to Jawaharlal Nehru when India went to the UN to complain against Pakistani aggression and was lumbered with the order to hold a plebiscite, on territory it claimed as its own. Similarly, today, the Indian argument that Kashmir should continue to be part of India because of its legal union with India through an Instrument of Accession (legitimacy rather than legality is the new mantra of our globalised world) has few takers. Nor does the ‘secularist’ angle – ‘Kashmir should not leave India merely because it has a Muslim majority’, help acquire Western sympathy because all western liberal democracies are based essentially on a core religious identity. How can one expect these Western states not to accede to the argument that Muslim-majority Kashmir should belong logically and naturally to Islamic Pakistan?

The case for Pakistan to make the necessary concession in favour of a multi-level negotiation comes from the fact that the ‘all or nothing’ approach to Kashmir has become an impediment to trade, development, civilian rule and democracy, and in any event, forcing such a solution on India appears unrealistic in the near-future. This form of realism marked the Musharraf plan which could contribute important elements to the package of ideas to move towards ‘principled’ negotiation.26

Current developments point in the direction of a cautious optimism with regard to a solution to the Kashmir problem that might be acceptable to India, Pakistan and the majority of the people of Kashmir. Public opinion in India continues to be in favour of a negotiated solution to the Kashmir problem. The initiative taken by the Hindu- nationalist BJP at the head of the NDA coalition under the leadership of Vajpayee to negotiate with Pakistan set an important precedent. It has been followed by the successor, the Congress-led UPA. A negotiated outcome to the Kashmir problem has emerged as a viable alternative to military action27 for the government of Pakistan, continuously in search of domestic legitimacy and international acceptability. The acquisition of nuclear weapons and missiles has helped Pakistan overcome the handicap of her relatively smaller arsenal of conventional weapons against India, and this transformation of conventional asymmetry into nuclear parity has facilitated a serious engagement in the ‘composite dialogue’. Finally, Pakistan’s nuclear threat has given further salience to the Kashmir problem by drawing the attention of a world keen to avoid regional nuclear conflict.

The time may be ripe for the steps we have indicated above. The threat to internal security has emerged as a major source of challenge to public policy making in India. A corollary to this is the entanglement of Indo-Pakistan rivalry with internal security, and its potential for nuclear war, which remains a source of great anxiety. These security concerns affect the flow of capital, investment, and trade. The leaders of both India and Pakistan have shown great concern for the opportunity cost of terrorism for the growth of trade, communication and development, and opened multiple channels of diplomatic negotiation. There is far greater realisation today that Kashmir, deeply evocative of the memory of India’s partition, is indicative of the incomplete character of national and territorial integration of both India and Pakistan. The rational politics of coping with sub-nationalism, which combines force with persuasion and accommodation, enriched by multi-level ‘principled’ negotiation, based on the multiple identities of actors and guided by interlocutor’s recommendations can help re-design space that was once considered rigid and immutable.

Is ‘Principled Negotiation’ Realistic?

The method of ‘principled negotiation’ advocated in this article marks several points of departure from the parameters that underpin conventional thinking about India- Pakistan dialogue. First, it requires India (and Pakistan) to look beyond the Simla Agreement that requires all issues between India and Pakistan to be sorted out bilaterally. Our approach requires China to be brought in as a third party with a stake in Kashmir. Secondly, it requires Indian thinking to take cognisance of the singularity of the Kashmir conflict and take cognisance of its regional dimensions. Thirdly, Pakistan has to take on board the fact that it is a multi-level negotiation where India might involve all opinions within Jammu and Kashmir at a lower level (as India already attempted in the Interlocutors initiative) while Pakistan can take into confidence its own stakeholders such as the army and the rulers of Pakistan-controlled Kashmir. But at the highest level, the negotiation should be confined to the three main stake-holders: India, Pakistan and China.

The revival of the stalled dialogue is squarely in the hands of the Prime Ministers of India and Pakistan. Where, one might ask, is the incentive for Mr Modi and Mr Sharif to take the risk? To answer this question, one has to understand that in game-theoretic terms, far from being a zero-sum game, it is a non-zero sum game between these two elected leaders. Both have major challengers at home; both need to show a major prize to regain their credibility. Some progress on anti-terrorism and the Mumbai trials will do this for Mr Modi; bringing Mr Modi to Pakistan in 2016 for the SAARC summit and a good trade- and aid-package between the two countries will do this for Mr Sharif. But, is such a radical initiative realistic in the current atmosphere of distrust and powerful outpouring of venomous rhetoric on both sides? One has to only hark back to the halcyon days of Atal Behari Vajpayee when the situation was just as desperate but still, a major breakthrough could be made. Turning a problem into an opportunity is what leadership is about.

Conclusion

The fiery rhetoric and the blame-game in the respective news conferences of Mr Sartaz Aziz and Mrs Sushma Swaraj have a sense of déjà vu about them. This stalemate represents a huge opportunity cost for the corporate sectors and civil society in both states just as the Chinese crisis has created an opportunity for South Asia’s entrepreneurs and the Greek crisis keeps European business focussed on their domestic problems, this could have been the time for the subcontinent to enter the global arena in an effective way. An equally missed opportunity is for the political and the military leaders of the two countries to join forces and intelligence information in order to subdue the various branches of terrorist networks linked to global terrorism. A third missed opportunity is Indo-Pakistan trade. Ironically, just as the NSA dialogue drama was unfolding, a report in Indian Express showcased vigorous trading in Pakistani textile by a private entrepreneur in Chandigarh with Indian customers happily purchasing large stocks of Pakistani deem superior to their Indian rivals.28

One of the most protracted, violent and contentious conflicts in the world, Kashmir has attracted much attention and scholarship29 with regard to a possible solution. However, in the absence of a consensus among the conflicting parties to work jointly towards a mutually acceptable outcome, I have argued in this essay, no serious or sustainable dialogue is possible.30

The way forward to break through this dangerous and costly stalemate is for India to rethink its strategy of how to engage Pakistan. First, India should bring in China as a negotiation partner to encourage Pakistan to focus squarely on eliminating terrorist training camps in Pakistan. Harking back to the Simla Agreement (1972), signed at the nadir of Pakistan’s fortunes, has the same effect as the Versailles Treaty (1919) had on Germany, egging noxious nationalism towards a ‘just war’ to retrieve lost national honour. Second, India should try to glean some useful elements from the composite dialogue of 1999 which packaged the issues into eight baskets. Third, the Musharraf Plan, which fell along with its author when the political climate in Pakistan changed, has some useful elements that could be put together to produce a coherent Indian strategy. This could become the basis of a ‘principled’ negotiation which focuses on issues and not positions and looks for win-win solutions.

That Kashmir currently has an elected coalition government of a regional Kashmiri party Peoples Democratic Party (PDP) and the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) as a junior partner should give India a window of opportunity in order to showcase the strength of Indian democracy. In a public opinion survey31 where I asked the question “do you consider yourself a citizen of India”, a majority of Kashmiris had pronounced themselves as citizens of India. Except the border districts where the army is in active operation and the ritualised bandhs and hartals, life in Kashmir most of the time is as normal as elsewhere in India. However, Kashmir has not been able to take advantage of the general boom in Indian economy because of the legal prohibition against land ownership by non-Kashmiris. The cost of the Kashmir conflict in this sense is largely borne by Kashmiris themselves in terms of missed trade and industry.

The energetic trips of Mr Narendra Modi to foreign lands – his achievements on this score alone outstrips any of his predecessors – will come to naught with regard to the Kashmir issue if India does not develop a coherent strategy to engage all the stakeholders. These include the Pakistani military, elected government, civil society, businesses in Pakistan; United States and China; and in India itself the BJP and the Congress party, the PMO, foreign ministry, defence ministry, home ministry, the elected government of Kashmir and the Hurriyat. This might seem as too large and disparate a constituency and in consequence it might seem impossible to generate consensus from within this constituency in support of a coherent strategy, but in the end that is what leadership is about. The longer India waits to get there, the costlier it would be to find an acceptable solution.

The sooner the actors, empowered as stakeholders, realise the true nature of what is at stake and make credible bids, the easier it would be to reach enduring solutions to conflicts that appear intractable. This would require the Indian public to be ready to engage in a ‘land for peace’ deal – not the easiest thing to do in a democracy as one knows only too well from the comparable case of Israel and the occupied territories in the enduring Middle-East conflict.

The three wars 1947-48, 1965 and 1999 and countless cross-border incursions as well as the action on the western front in India’s Bangladesh liberation war in 1971 have shown that Pakistan cannot afford to completely let go off Kashmir; and India cannot quite manage to solve the Kashmir issue by force. India has refused plebiscite on the ground that Kashmiris through regular elections have expressed their willingness to be part of the Indian Union. Just as India, when it comes to Indo-Pakistan dialogue, seeks to push Kashmir unto the back burner, Pakistan tries to bring Kashmir back in again. Thus, it seems the aborted trip of Mr Sartaj Aziz is being interpreted by some commentators as a “victory” for Pakistan because the circumstances which led to its termination are being seen as Indian obduracy and an effort to dictate terms to Pakistan about what could be talked about and what had to be excluded. Be that as it may, this kind of short-term triumphalism can only harden attitudes in India and lower the chances of a negotiated outcome even further. The time has come for the Prime Ministers of India and Pakistan to take the initiative back from war-mongers. Forceful and quiet diplomacy rather than the gladiators of the talk-show and newspaper columns should be the order of the day.

About the author:

* 1. Professor Subrata Kumar Mitra is Director and Visiting Research Professor at the Institute of South Asian Studies (ISAS), an autonomous research institute at the National University of Singapore. He can be contacted at [email protected]. The author, not ISAS, is responsible for the facts cited and opinions expressed in this paper. The paper is based on a talk he delivered at the Researchers’ meeting, ISAS, on 3 September 2015. He is grateful to the participants and the anonymous referees for their valuable comments.

Source:

This article was published by ISAS as ISAS Working Paper Number 209 (PDF)

Notes:

2 Delhi has hinted that the latest fiasco may not necessarily mean a prolonged break in the dialogue. As the External Affairs Minister Sushma Swaraj put it, there are no full-stops in Indian diplomacy towards Pakistan. C. Raja Mohan, “Not with you, nor without you”, Aug 25, 2015. http://indianexpress.com/article/opinion/columns/not-with-you-nor-without-you.

3 In his excellent and balanced article, former Pakistani diplomat Hussain Haqqani points out some of the costs of the present stalemate to Pakistan and India. See Hussain Haqqani, “Pakistani Hate, Indian Disdain”. Foreign Policy http://foreignpolicy.com/2015/08/28/pakistanihateindiandisdain/.

4 “If the balance of power changed in India’s favor in 1971 the nuclearisation of Pakistan by the late 1980s ended Delhi’s presumed advantage. Since then, we have a stalemate. Pakistan has shown the capacity to destabilize Kashmir and foment terror across India. But it has not been able to change the territorial status quo in Kashmir. Delhi, on the other hand, has not been able to find an effective answer to Rawalpindi’s proxy war. Nor has India been able to compel Pakistan to normalize bilateral relations through the expansion of economic cooperation and settlement around the status quo in Kashmir. Neither side knows how to break this stalemate.” (Emphasis added). Raja Mohan, op. cit.

5 This method, called ‘principled negotiation’ or ‘negotiation on the merits’, can be boiled down to four basic points. These four points define a straightforward method of negotiation that can be used under almost any circumstance. Each point deals with a basic element of negotiation, and suggests what you should do about it. 1. People: Separate the people from the problem. 2. Interests: Focus on interests, not positions. 3. Options: Generate a variety of possibilities before deciding what to do. 4. Criteria: Insist that the result be based on some objective standard.’ See Roger Fisher, Bruce Patton and William Ury, Getting to yes: negotiating agreement without giving in (New York, 2011), For a detailed review of the literature on ‘principled negotiation’ and an application of the model to the Kashmir conflict, see Subrata Mitra and Radu Carciumaru, “Beyond the ‘Low-Level equilibrium Trap’: Getting to a ‘Principled Negotiation’ of the Kashmir Conflict” in the Irish Studies in International Affairs, Vol. 26 (2015), 1–24.

6 See The Hindu, July 11, 2015, and ‘Blame Nawaz’, in The Dawn, August 23, 2015. http://www.dawn.com/news/1202209/blame-nawaz.

7 Ibid.

8 The All Parties Hurriyat Conference (APHC) is an alliance of 26 political, social and religious organisations formed on 9 March 1993 as a political front to raise the cause of Kashmiri separatism. This alliance has historically been viewed positively by Pakistan as it contests the claim of the Indian government over the State of Jammu and Kashmir. Wikipedia, visited on 7/9/2015

9 South Asia Terrorism Portal, accessed on September 22, 2013, available at: http://www.satp.org/satporgtp/countries/india/states/jandk/data_sheets/annual_casualties.htm

10 See Subrata Mitra, “War and Peace in South Asia: A revisionist view of India-Pakistan relations” Contemporary South Asia, Vol 10, Issue 3, 2001, pp.361-379, for a general version of this game where the numbers are presented in the form of ordinal scores.

11 India being the larger country with a bigger economic base, one can argue that the cost of war is higher to Pakistan on a per capita basis. However, that does not change the logic of the main argument, leading towards a suboptimal outcome for both.

12 William Zartman, and Jeffrey Z. Rubin eds. Power and Negotiation (International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis, Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2000), p. 12

13 According to Axelrod, four conditions – namely, knowledge, proximity, reciprocity and recursiveness – could produce the unofficial ‘Christmas truce’ between the two sides. Axelrod, Robert, The Evolution of Cooperation (Revised ed.) (New York: Perseus Books Group, 2006).

14 Partha S. Ghosh suggests, “probably just like the Cold War came to an end without giving any prior notice, the problem of Kashmir too could well be solved one day to the surprise of all Kashmiris, Indians and Pakistanis”. See, Partha S. Ghosh, “Kashmir Revisited: Factoring Governance, Terrorism and Pakistan, as Usual”, Heidelberg Papers in South Asian and Comparative Politics, vol. 54, 2010, p.13.

15 The Strategic Arms Limitation Talks(SALT) were two rounds of bilateral conferences and corresponding international treaties involving the United States and the Soviet Union on the issue of arms control.

16 See Subrata K Mitra, “War and peace in South Asia: A revisionist view of India-Pakistan relations”, Contemporary South Asia, Vol 10, Issue 3, 2001, pp.361-379, in which this has been demonstrated in terms of a two-person, zero-sum game that leads to a prisoner’s dilemma situation.

17 I. William Zartman, Ripe for Resolution (New York: Oxford University Press, 1989)

18 See, Subrata Mitra, “The Rational Politics of Cultural Nationalism: Subnational Movements of South Asia in Comparative Perspective”, British Journal of Political Science, Vol. 25, Issue 1, January 1995, pp. 57-77.

19 See Subrata K Mitra and A. Lewis (eds.), Subnational Movements in South Asia (Boulder/Colorado: Westview, 1996), for detailed analysis of cases from India and its neighbours.

20 See Subrata Mitra, “Sub-National movements, Cultural Flow, the Modern State and the Malleability of Political Space: From Rational Choice to Transcultural Perspective and Back Again” in Transcultural Studies 2 (2012) E-journal, Excellence Cluster, Heidelberg, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.11588/ts.2012.2.9155.

21 The conflict cannot be perceived by either India or Pakistan, as a zero-sum territorial dispute anymore.

22 The transformation of the de facto frontiers to de jure can be a result of the negotiation and not an assumption to begin with. I am grateful to Mr Javed Burki for this comment.

23 Article 370 of the Indian Constitution protects the separate status of Kashmir. Findings from a survey of the Kashmiri population show that 53% of the electorate of Kashmir Valley and 80% in Jammu think of themselves as citizens of India. This shows the popular base in Kashmir for an Indian-style secular democracy. See Subrata K Mitra, “Citizenship in India: Some Preliminary Results of a National Survey”, Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. XLV, No.9, February 2010.

24 The freeing up of the Indian army from the Kashmir imbroglio may not be in the best interest of the Chinese but then, there is the possibility of reciprocity in terms of a swap of the disputed territory in the western border with that of the contested claims in the East.

25 See Sajad Padder, “The Composite Dialogue between India and Pakistan: Structure, Process and Agency”, Heidelberg Papers in South Asian and Comparative Politics, no. 65, Feb 2012. Padder explains the strength of this visionary agreement in terms of dividing the contents of India-Pakistan relations into eight baskets of issues namely, “Peace and Security including confidence building measures(CBMs); Jammu and Kashmir (J&K); Siachen; Wullar Barrage/Tulbul Navigation Project; Sir Creek; Economic and Commercial Cooperation; Terrorism and Drug Trafficking; and, Promotion of Friendly Exchanges in various fields”.

26 See Javed Naqvi, “Musharraf’s four stage Kashmir peace plan: we can make borders irrelevant: India”, in Dawn, Dec 6, 2006

27 In view of recent border skirmishes, Sartaj Aziz – Pakistan’s Advisor on National Security and Foreign Affairs – stated that Directors General of Military Operations (DGMOs) of Pakistan and India “should meet immediately and discuss ways and means to stop the current spate of firing along the working boundary…” (See “Kashmir gun battle leaves several dead” August 24, 2014, http://www.aljazeera.com/news/asia/2014/08/kashmir-gun-battle-leaves-several-dead- 201482411568738820.html). Moreover, Pakistan and India, in view of the withdrawal of NATO forces from Afghanistan, would greatly profit by joining forces to fight the terrorists that are likely to become more active in destabilising not only the Frontier Regions of Pakistan, but other parts of the region as well, including and particularly Kashmir.

28 Nirupama Subramanian, “Unbothered by NSA talks, they pick up the threads at an India- Pakistan fair”, The Indian Express, August 23, 2015, http://indianexpress.com/article/india/india- others/unbothered-by-nsa-talks-at-an-india-pakistan-fair-they-pick-up-the-threads/.

29 One of the best known list of possible solutions is from Sumit Ganguly. See Sumit Ganguly, The crisis in Kashmir: portents of war, hopes of peace (Washington, DC, 1997), pp. 131–50.

30 The latest in the series of specific measure is the recent agreement among journalists and newspaper owners in both parts of Kashmir to share information. However, in the absence of the support of the key stakeholders, such initiatives have little chance of making real progress. See Islamabad, September 7, 2015 Updated: September 7, 2015 02:28 IST Newspapers in Kashmir, PoK to share content. Reported in The Hindu 7/9/2015

31 See Subrata Mitra, “Citizenship in India: Some Preliminary Results of a National Survey”, Economic & Political Weekly, Vol. XLV, No.9, February 27, 2010, pp. 46-53.

such a biased article, I thought i was reading from a non indian news portal. correct me if i am wrong