To Shoot Or Not To Shoot? Southeast Asian And Middle Eastern Militaries Respond Differently – Analysis

By James M. Dorsey and RSIS

An analysis of the Middle Eastern and North African militaries has produced a laundry list of literature, much of which was either valid for a specific post-World War II period or highlighted one of more aspects of military interest in the status quo or attitudes towards political change. Leaving aside the geopolitical differences between Southeast Asia and the Middle East and North Africa, a comparison of the transition in both regions brings into focus the building blocks that are needed for an armed force to embrace change. Southeast Asian nations succeeded whereas the countries in Middle East and North Africa, with the exception of Tunisia, have failed for several reasons.

By James M. Dorsey and Teresita Cruz-Del Rosario*

A Crumbling Façade

A lieutenant colonel when he toppled the Egyptian monarchy in 1952, Gamal Abdel Nasser emerged as the leader of unaligned Arab nationalism. By the time of his death in 1970, Nasser’s brand of nationalism had informed various related military and security force-backed regimes across the region. These included those of the rival wings of the Arab socialist Baath Party in Syria and Iraq, the revolutionary government that emerged in Algeria from a bitter, anti-colonial war, and that of 27 year- old Libyan army colonel Muammar Qaddafi, who overthrew the Libyan monarchy with the intention of molding his country’s in Nasser’s image. Regimes reliant on the military and/or security forces became the norm for Arab nations. Their resilience and longevity persuaded government officials, scholars, pundits and journalists that the Arab world, in contrast to Asia, Africa and Latin America, was exceptional. The notion of Arab exceptionalism blinded them to political, social and economic undercurrents that first exploded in their faces with the rise of political and jihadist Islam and finally with the 2011 Arab popular revolts.1

By the same token, Southeast Asia witnessed in that same period a rise of military rule. In Indonesia, General Suharto brought about the New Order, a regime built on the ashes of a violent coup against the Communists in 1965 that removed President Sukarno from power. It would take 35 years for Suharto to be ousted from office by a popular uprising supported by a wing of the military that returned the country to democracy. Similarly, the Philippines endured 21 years of martial rule under a military-backed civilian government headed by President Ferdinand Marcos. Marcos was toppled in 1986 and forced into exile when a group of disgruntled military officers known as the Reform the Armed Forces (RAM) defected and supported a popular revolt.

At the outset, military-backed regimes in the Middle East and North Africa and in Southeast Asia had much in common. The military was either the government or propped up a dominant political party. Elections, if held at all, were ritualised exercises that served to rubber stamp assemblies and political leaders and provide a hollow façade of popular participation by an otherwise quiescent citizenry.

That façade crumbled with popular revolts and political transitions that swept power from military or security force backed-regimes in Indonesia, the Philippines, Thailand, Myanmar, Egypt, Tunisia, Libya and Yemen, and rocked the foundations of those in the Middle East and North Africa that managed to remain in office. With the exception of Thailand, political change has proven to be more sustainable in Southeast Asia than in the Middle East and North Africa where Tunisia has so far emerged as the only relative success story.

Indonesia, the Philippines and Tunisia continue to see political power change hands as the result of free and fair elections. Thailand is Southeast Asia’s odd man out. Its military supported a popular uprising in 1992 that led to the restoration of democracy, yet intervened again in 2006 and 2014 to topple two democratically-elected regimes. Egypt’s first and only democratically president, Mohammed Morsi, was ousted in a military coup in 2013 that brought to power general-turned- president Abdel Fattah Al Sisi and a regime more brutal than that of former president, Hosni Mubarak. Libya, Yemen and Syria, where a popular revolt was brutally suppressed, have descended into mayhem and civil war that have sparked varying degrees of foreign intervention. Iraq, where the country’s autocrat, Saddam Hussein, was toppled in 2003 by a US-led invasion, teeters on the brink of breaking up and together with Syria has made jihadist Islam as potent a force of political change as any other.

There is much to be learnt from both the similarities and the differences in the political transitions of Southeast Asia and the Middle East and North Africa. Transitions did not always aim to establish a democracy. But when democracy was the goal, transitions did not always involve successful efforts to assert civilian control over the military in a bid to remove any possibility of direct military engagement in political affairs. “No transition can be forced purely by opponents against a regime which maintains the cohesion, capacity, and disposition to apply repression,” noted political scientists Guillermo O’Donnell and Philippe C. Schmitter.2

The record shows that successful transitions depend on participation of at least one faction of the military as well as on civil society engagement in line with game theory that postulates that democratisation is possible when moderates in the ruling elite cooperate with civil society and/or opposition forces to fend off advances by hardliners.3 It often involves the military increasingly viewing the cost of governing rather than ruling4 as too high and seeing controlled liberalisation as the solution.5

In discussing the popular Arab revolts in the second decade of the 21st century, political scientist Philippe Vincent Droz argued that the participation of the armed forces constituted the “tipping point” in the downfall of regimes in Egypt, Tunisia, Libya and Yemen.6 This was certainly true in Egypt and Tunisia where the military by and large saw a change of leader, if not a change of regime, as in its interest. The picture in Libya and Yemen – where the military split or suffered from significant defections and where the fall of the autocratic leader led to mayhem, insurgency, civil war and/or foreign intervention – is more complex. The popular revolt in Bahrain was thwarted by brutal government repression and the Saudi-led military intervention by friendly Gulf states. In Syria, Gulf states for differing reasons saw the fall of the regime as in their interests but increasingly funded and supplied arms to anti-regime forces that did not see greater freedom and accountability as cornerstones of transition but their own religiously-inspired version of autocracy as an alternative to the ruthless regime of Syrian president Bashar al-Assad.

The contrast with the role of the military in the political transitions of Indonesia in 1998 and the Philippines in 1986 could not be starker both in terms of the alignment of factions of the military with civil society groups and protesters and with regard to the nature of the alliance. In Egypt and Tunisia, it was the military as an institution that saw a change of political leadership as in its interest. That interest, unlike in the cases of Indonesia and the Philippines, translated into the Egyptian and Tunisian militaries by and large refusing to come to the embattled autocrat’s rescue and making clear to the leader that it was time to go. The Egyptian and Tunisian militaries, despite protesters’ slogan that the ‘military and people are one,’ did not go beyond that to work with civil society to ensure political change as did the Indonesian and Philippine armed forces. On the contrary, the Egyptian military, two years after the toppling of Mubarak and one year after Morsi took office, exploited with the security forces widespread popular discontent to stage a coup that reversed all gains achieved by the 2011 revolt.

The result of the differences in the way militaries or powerful factions within the Indonesian and Philippine militaries defined their interests and engaged with civil society as opposed to their Arab counterparts is evident not just in the fact that the Southeast Asians witnessed transitions away from autocracy but also in the restructuring of civil-military relations. Indonesia is possibly the only country in both regions in which the civilian government succeeded in asserting control of the armed forces on the back of a series of well-sequenced reforms that unequivocally returned the military to the barracks. The Philippines achieved a degree of civilian control despite several failed coup attempts but institutionalisation remains a tenuous and challenged process.

Similarly, Myanmar, several years after its 2012 transition, remains locked in a power struggle between the military and civilian forces with the armed forces continuing to exert their weight behind a veneer of democratic reforms. In the Middle East, only Tunisia and Turkey can boast of a similar achievement. The Tunisian military which had been defanged and sidelined by the country’s ousted autocrat, Zine El Abidine Ben Ali, a product of the security rather than the armed forces, was the one Arab military with a vested interest in political transition. That eased the establishment of civilian control.

Turkey’s experience differs fundamentally from that of any other Middle Eastern or Southeast Asian nation. Its assertion of civilian control occurred in a pluralistic, democratic environment in which the government could rely on the European Union, which demanded civilian control of the military as a pre-condition for accession to the EU. Nevertheless, historically, Turkey and Thailand, which lags far behind in civilian control, display similarities. Both militaries see themselves not only as protectors of their countries’ borders but also of its fundamental ideology or power structure. While Turkey appears to have put its era of regular military interventions behind it, Thailand is experiencing its 13th period of military rule in 80 years.

The lessons to be learnt from a comparison of political transition in Southeast Asia and the Middle East and North Africa lie in understanding why factions of the military in Indonesia, the Philippines and Myanmar believed they had a vested interest in change and in aligning themselves with civil society as opposed to most Arab militaries that at times favored change of leader but not of the system and viewed civil society as a potential threat that needed to be kept under the thumb.

Militaries in Southeast Asia, the Middle East and North Africa share a similar post-colonial experience. Countries in both regions emerged from colonialism in the wake of World War II. They were fragile states that were grappling with decolonisation, post-war reconstruction, insurgency threats, economic and social inequalities, and overburdened state institutions that were in their infancy. Their militaries grew increasingly frustrated with their countries edging ever closer to chaos as feuding politicians proved incapable of papering over internal rifts. Increasingly, the militaries viewed themselves as guardians of national security, stability, and law and order. To live up to their self-defined role, militaries muscled their way into “political decision-making, commercial activities, social development, and civil action projects” in addition to suppressing insurrections.7 The militaries’ growing political role in Southeast Asia and the Middle East and North Africa was buffeted by United States (U.S.) and Soviet support for their respective allies as part the Cold War.8

Asia: A Pivot towards Democracy

In many ways, the evolution of thinking in the Turkish military resembles that of the militaries of Indonesia, the Philippines and Myanmar. This is true despite the fact that the Turkish military only intervened for brief periods of two to three years before returning to the barracks whenever it felt that the countries pluralistic albeit flawed democracy had failed or it feared that adherence to Kemalist secularism was threatened by political Islam. The approach of the Turkish, Philippine and Myanmar militaries contrasted with that of militaries and intelligence and security forces in countries like Algeria, Libya, Egypt, Syria and Yemen. They recognised that the world was moving away from condoning military rule and towards a more democratic form of governance. In addition, Southeast Asian militaries realised that “not only is working for a dictator a bad bargain in the long run”9 but also for the military. Like the Turkish military, armed forces in Southeast Asia understood that they lacked the wherewithal to govern, run an economy, manage a massive bureaucracy, engage in rehabilitation in the wake of natural disasters, and maintain social harmony among a variety of ethno-linguistic groups and communities.

Myanmar exemplifies the keen political understanding of various Southeast Asian militaries. In control of the state and dominant in national politics since it first assumed power in 1958, the military has repeatedly confronted challenges by re-inventing itself without compromising its overarching role.

Popular protests and mounting dissatisfactions failed to force the military to surrender power. In contrast to other militaries in Southeast Asia or the Middle East and North Africa who were reactive in their responses to popular pushes for change, the Myanmar Armed Forces was often proactive. That led them in late 2010 to initiate a political transition towards significantly greater freedom and democracy that nonetheless left the military effectively in charge of the process and guaranteed it a measure of continued control. In effect, the military saw controlled change as the best way to protect its interest.

The military’s evolution to the point where it was willing to initiate its staged surrender of a measure of control of politics resembled the principle of Arab militaries that were not subject to personalised control by the ruler who preferred to rule but not govern.10 Myanmar scholar Robert Lee Huang argued that the Myanmar military’s ceding of dominance was “in fact an evolving strategy originally designed by the tatmadaw (the military) to institutionalise the military’s influence over government, though without the responsibility for the direct administration of the state.”11 Of all the lessons to be drawn from a comparison of Southeast Asian and Middle Eastern and North African military attitudes towards political change, the Myanmar experience may prove to be the one that turns out to be the most relevant.

In the same way that the Egyptian military ruled but did not govern for much of Egypt’s post World War II history by identifying key areas that it wished to control beyond government supervision – national security, its budget, its relationship with the U.S., and immunity for its personnel – Myanmar’s armed forces operated on the principle of what political scientists Juan J. Linz and Alfred Stepan called ‘reserve domains,’. This involves the securing of prerogatives or what the two scholars termed ‘authoritarian enclaves’, in a bid to regain a popular support base in an increasingly restive society.12

Political change in Myanmar was driven by the military’s inability over the years to fully establish control of a society in which significant segments repeatedly staged mass protests and that was wracked by armed rebellions on the periphery. Initially, the military sought to coopt groups sectors like private business and monasteries that it had earlier been unable to wholly whip into line.13 The moves failed to avert economic crisis and mass protests in 1988 and prevent the National League for Democracy (NLD) headed by Aung San Suu Kyi from winning a landslide victory in elections in 1990, prompting the military to refuse to recognise the poll.

Two key events preceded political transition in Myanmar in the second decade of the 21st century: the unprecedented criticism by the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) of the harsh military crackdown on protests in 2007 and its call for a transition to democracy and the military’s inability to manage rehabilitation of the devastating effects of Cyclone Nargis in 2008.14 The cyclone hit Myanmar in a period of prolonged economic collapse, endemic poverty, and long-standing international rejection that eroded all vestiges of regime legitimacy – all factors that also threatened Myanmar’s vast economic interests. “In the cyclone’s aftermath, the willfully merciless behavior of the junta in hampering relief efforts and thereby facilitating thousands of unnecessary deaths severely embarrassed ASEAN. Had Myanmar been a democracy when the cyclone struck, the regime could not have obstructed humanitarian relief without risking its own demise,” noted Southeast Asia scholar Donald K. Emmerson.15

If the ASEAN condemnation and the military’s handling of the cyclone suggested that the writing was on the wall, scholars argued that the military’s ultimate initiation of political transition had been in the works since 1993 when Myanmar first started drafting a new constitution in a process that stalled for several years and had largely been decided and concluded prior to the 2007 protests.16 “This was the beginning of the seven-step roadmap towards a ‘discipline-flourishing democracy’ first announced in 2003 by then…premier Khin Nyunt…to ease international pressure … Two critical events, the (2007) ‘Saffron Revolution’ and Cyclone Nargis further undermined the credibility of the…regime … Neither crisis derailed the tatmadaw’s transition plans, though they may have contributed to the decision for the tatmadaw leadership to move forward the process of re-civilianising the regime,” Huang noted.

Just like the Egyptian military, the Myanmar Armed Forces enshrined its red lines in the constitution that was finally adopted in 2008. The constitution barred Myanmar citizens whose close families were foreigners from assuming the presidency. That effectively prevented Suu Kyi from becoming president after her party won another landslide victory in 2015. The constitution also guarantees the military a quarter of seats in parliament, giving it the ability to veto constitutional changes. The military keeps control of the defense, interior and border and police ministries and under the constitution retains the right to re-take control of the government, including management of the economy, if deemed necessary.

Al Sisi opted for restoration of the regime that existed prior to the toppling of Mubarak and brutal oppression of all opposition and dissent. In contrast, Myanmar’s armed forces have sought to demonstrate their sincerity in conditionally supporting gradual transition to a more open and transparent society. They have also gone to some length to recast their image. The military’s top commander, GEN Min Aung Hlaing17 commented, “We need a mature and stable political situation in our country. We need to gradually change.” A retired general added that the armed forces “have an exit strategy. They will fade away from politics day by day.”18

GEN Min Aung Hlaing, has carefully sought to craft a public image from that of his predecessors, President Thein Sein, a former general, and Than Shwe, who ruled with an iron first for a decade before stepping aside to make place for the nominally civilian government headed by Thein Sein that governed until his military-backed Union Solidarity Development Party (USDP) lost the election. “I am not the old guard,” the general said in unpublished portions of a Washington Post interview that he posted on his Facebook page.19

If the graduation of the Myanmar military towards a more open political system potentially has lessons for the Middle East and North Africa, tumultuous, messy and bloody transition in the region as well the see-saw development in Thailand serves as a justification for the Myanmar Armed Forces’ insistence on guiding the transition process.

Initially, the Thai military like its Burmese counterpart, concluded after its take-over in September 2006 that resulted in its mismanagement of the economy and negative growth, that it too would be better off governing but not ruling. After five years in government, Thailand’s military rulers called in 2011 for elections in which civilians would regain control of government. Thai military acknowledgement of its limits proved however to be short-lived. Its rejection of civilian control of the military was evident when in May 2014, it again staged a coup to topple the government of former Prime Minister Yingluck Shinawatra. Its record since has been no better: economic slowdown and simmering civil unrest will either lead to a breakdown of the political order or more likely prompt another military re-think. This does not bode well for Thailand.

The 2014 coup followed military support for six months of primarily middle and upper class protests against the government of Yingluck Shinawatra and her brother and fugitive predecessor Thaksin Shinawatra.20 In some ways, the renewed military intervention against the Shinawatras had long been in the making. Many of the officers who had been part of the 2006 coup supported the creation of an anti-Thaksin coalition in 2008 and engineered the violent suppression of pro-Thaksin demonstrations in 2010.21

Much like the Arab militaries, the royalist Thai military that views itself as the guardian of nation, religion and monarchy saw its interests best served in the preservation of the status quo or what Thailand scholar Charles Keyes termed the ‘network monarchy’22 – the alliance between the palace, the bureaucracy, big business and the armed forces. The Thai military saw this alliance as being threatened by the populist policies of the Shinawatras and their lower class power base. As a result, the military-backed protests and the coup were designed to ensure control of Thailand by the monarchy and the military. It also served to warrant a smooth transition once ailing 87-year old King Bhumibol Adulyadej passes away.23 Those goals seemingly persuaded the military to concentrate power in its own hands in contrast to coups in 1991 and in 2006 when it relied on technocrats to run the government and manage the economy.24

Much like the Egyptian military that intervened in 2013 to reverse the achievements of a popular revolt that had ousted long-standing President Mubarak and re-establish the status ante quo, the Thai military was aided by perceptions of a national crisis and the fact that it was far more united than the country’s civilian political forces. It could also build on a historical legacy of a strong military that was supported by the monarchy and given a degree of legitimacy.25 Thailand’s military effectively governed the country for almost half a century until 1973 when student protests convinced the king backed by a group of senior officers to initially remove it from government, rather than power. As a result, the Thai military like the Egyptian military and the Turkish Armed Forces until the rise of Recep Tayyip Erdogan as prime minister ensured that it remained shielded from civilian control.

Nonetheless, also similar to Egypt, failure to effectively tackle a worsening economic situation, shattering public expectations and growing discontent26, and differences within the military itself, is ultimately likely to force the Thai military to seek a way to withdraw from power without losing control by working through proxies. Recent reports suggest increased factionalism in and politicisation of the military fueled in part by greater competition for coveted jobs that has eroded corporatism.27 The differences have persuaded senior military commanders to publicly pledge that there would be no attempts from within the military to remove Prime Minister Prayut Chan-o-cha, the general who retired after staging the 2014 coup. Since his appointment as military commander in September of last year, General Udomdej Sit-abutr has reshuffled some 400 officers who had served in units involved in past coups.28

Statements by Prayut29 as well as the interim constitution he promulgated and efforts to draft a new constitution suggest that the various military factions continue to see a return to a full democracy as contrary to their interests. These factions are likely to opt for an option in which they would be the behind-the-scene guide. The 2014 coup was but the latest intervention by the Thai military dating at least to the 1950s to prevent any true democratic system developing in Thailand,” Keyes noted. Keyes argued that the network monarchy favored “despotic paternalism” first introduced in the late 1950s by Field Marshal Sarit Thanarat.30 The Thai military is nonetheless likely to find it easier to engineer its exit than its Egyptian counterpart given that it only has to take into account the monarchy. It also does not have to contend with meddling by foreign powers who in Egypt are bent on dictating the course of events.31

Military interest in the change in Indonesia and the Philippines was fueled by former presidents Ferdinand Marcos and Suharto’s divide and rule tactics that favored their cohorts and relatives in the armed forces at the expense of career officers and the integrity of the military as an institution.32 Lee argued that personalisation of the military ensured loyalty to Marcos. However, it is difficult to project this argument as a universal principle. The underlying principle of civil-military relations in the Middle East and North Africa of distrust between the ruler and his armed forces meant that those militaries that were not subject to personalised control by rulers preferred to rule rather than govern.33

Moreover, beyond the fact that personalisation ultimately backfired in the Philippines, it was also called into question by experiences in Morocco and Jordan. The Moroccan and Jordanian militaries are professional institutions that enjoy a degree of institutional autonomy. They remained nonetheless loyal to the regime in 2011 when mass anti-government protests erupted, acting on the instructions of the monarch not to employ violence. Their obedience stemmed from their professionalism rather than from a personal relationship with the ruler.34

In the case of the Philippines, Marcos moved almost immediately after his declaration of martial law to undermine the autonomy of the military and ensure the personal loyalty of its commanders. He built a patronage system by forcibly retiring senior officers and bypassing standard procedures. Promotions and extensions of tenure were controlled by Marcos, who appointed officers from his home province of Ilocos Norte. He named his first cousin, General Fabian Ver, commander of the Presidential Security Command (PSC) and later chief of staff. The personalised nature of Marcos’ control also impacted military budgets and deployments with no input from the officers’ corps.35 Dissenting military personnel were purged, deported, imprisoned, tortured and/or executed. The mere perception of disagreement or a challenge was reason enough for retaliation. Men like Marcos and Suharto understood the military’s ability to act against them and the need to control “politically exuberant militaries.”36 Filipino General Rafael Ileto, an opponent of the declaration of martial law in 1972, was let off lightly. Ileto was exiled as ambassador to Turkey and Iran.37

The military careers of some 27 of the 34 military generals who were considered loyal were often extended beyond the age of mandatory retirement by the time martial law was declared. In 1986, when the People Power revolt erupted, 22 serving generals were beyond the age of retirement.38 Ultimately, Marcos’ micro-management of the military backfired as discontent in professional ranks mounted. They resented violations of their professional ethos and loss of their prerogatives. The tensions were evident in the pro-longed, deep-seated rivalry between Ver and Brigadier General Fidel V. Ramos, the head of the Philippine Constabulary and the Integrated National Police. Anger at favouritism, nepotism and corruption sparked the formation of the Reform the Armed Forces Movement (RAM) headed by Defense Minister Juan Ponce Enrile and Lt. Col. Gregorio “Gringo” Honasan. Enrile and Honasan went on to play prominent roles in the 1986 popular revolt against Marcos after reaching out to opposition groups and RAM joining a coalition of pro-democracy movements that was seeking Marcos’ removal from power. The two men were joined by Ramos who announced his defection on 22 February 1986. Ramos’ move proved to be the turning point in the effort to topple the Marcos regime. The story of Suharto’s fall in 1998 followed a similar pattern.

Middle Eastern Militaries: Power at Whatever Price

In July 2013, Egypt’s existential struggle between the military and the Muslim Brotherhood led to the overthrow of Morsi, the country’s first democratically elected president. This highlighted a fundamental difference with Southeast Asian nations that relatively successfully managed political transition. In Middle Eastern and North African countries, the absence of a civil society capable of asserting itself and expressing popular will has taken its toll on the process of political and social change.

The problem, said political scientist and journalist Rami Khouri, was not military and security forces’ lack of “capable individuals and smart and rational supporters; they have plenty of those.” Rather, it is “the lack of other organised and credible indigenous groups of citizens that can engage in the political process and shape new constitutional systems that is largely a consequence of how military officers, members of tribes and religious zealots have dominated Arab public life for decades.”39

The tumultuous events of recent years have demonstrated that Arab militaries have learnt little from the 2011 popular uprisings. By defining legitimate, peaceful, democratic opposition to the government and the armed forces as terrorism, Egyptian supreme military commander, vice president and defense minister General Abdel Fattah Al-Sisi joined the likes of Bahraini King Hamad bin Isa Al Khalifa; King Abdullah of Saudi Arabia; and embattled Syrian President Bashar al-Assad.

These men gave the battle against political violence and terrorism a new meaning. The Brotherhood’s mass protest against the Egyptian coup, demonstrations against Bahrain’s minority Sunni rulers despite a brutal crackdown in 2011, and intermittent minority Shiite protests in Saudi Arabia were all largely peaceful. However, these protests were brutally suppressed. In Syria, the protests against President Assad morphed into an insurgency and civil war only after the regime persistently responded with military force and brutality. Concurrently, discriminatory Shiite rule in Iraq gave birth to the Islamic State, the jihadist group that controls large swathes of territory in Syria and Iraq that threatens the territorial integrity of both countries and could rewrite the borders of the Middle East.

In many ways, the redefinition of terrorism revived the notion of one man’s liberation fighter is another’s terrorist. It was designed to force domestic public opinion and the U.S. to choose between autocracy or illiberal democracy and the threat of terrorism, an echo of the argument used by ousted autocrats including Egypt’s Hosni Mubarak, Tunisia’s Zine El Abedine Ben Ali and Yemen’s Ali Abdullah Saleh, to justify their repressive policies.

Many Arab militaries do “not rely much on the so-called historical and highly controversial legitimacy of the kind by the hadith (the sayings of the Prophet) tradition: ‘obey those that wield power,” writes researcher Elizabeth Picard. Instead, they claim a “revolutionary legitimacy gained through political struggle, or in the case of Algeria, armed struggle,” she wrote, referring to the Algerian war of independence. Picard added, “In many circumstances this legitimacy proves strong enough to resist the erosion caused by the regime’s mediocre achievements on the regional as well as the domestic level, and to survive internal feuds between rival factions.”40

Middle Eastern and North African militaries in contrast to those in Southeast Asia were not exposed to U.S. efforts to promote civil-military relations, eventual civilian control of the military and respect for human rights. This is despite the fact that civil society in the region was the beneficiary of significant funds to encourage the development of pluralistic and democratic values. A rare study of civil-military relations in the Arab world conducted by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) prior to the 2011 revolts concluded that “the ‘ripeness’ of many countries in this region for major programs in civil-military relations is problematic.”41 USAID’s conclusion was in line with U.S. policy that like its predecessor Britain, and its main rival for decades, the Soviet Union, favoured stability in the Middle East and North Africa by supporting autocratic rule rather than promotion of democracy that risked instability. By contrast, the study suggested that that there was “ample opportunity to begin serious work” on civil-military relations in the Philippines.42 The U.S., despite having rocky relations with Suharto’s military at times, did fund a number of civil-military-related programs in Indonesia.43

Government attitudes towards the military follow a pattern across the Middle East and North Africa based on the fact that rulers, irrespective of whether they hail from the military or not, distrust their armed forces. Their distrust was rooted in the Middle East and North Africa’s post-colonial history that until the 2011 popular revolts was pockmarked by military coups rather than civil unrest. The Middle East witnessed 82 military interventions in political life in the years between 1961 and 1980, 58 of which were successful.44

As a result, rulers often relied on security or parallel military forces rather than the armed forces to enforce internal security. The principle of rule rather than govern adopted by Middle Eastern and North African militaries and security and intelligence services meant that they often sought to centralise their power and quietly expand their influence within the state, society and the economy. Political scientist Charles Tripp coined the phrase “shadow state” to describe the process in Iraq45 while Turkey has long groped with the notion of derin devlet or the Deep State.46 Professionalisation often served as a way to depoliticise the military. It also meant that Arab militaries rigidly adhered to conventional warfare dogmas and were unprepared for irregular wars that have become the norm as a result of insurgencies and the rise of armed Islamist and jihadist groups.

Nonetheless, the complex relationship between rulers and militaries has sparked a number of scholarly attempts to classify armed forces in the Middle East and North Africa in a bid to analyse relationships and determine how they might respond to times of crisis and civil upheaval. Robert Springborg, a prominent student of Arab militaries uses sociologist Max Weber’s concept of sultanism that “tend(s) to arise whenever traditional domination develops an administration and a military force which are purely personal instruments of the master”47 to describe rulers’ personalised and concentrated power that was dependent on coercion.48 Sultanism, an approach found primarily in the Middle East and North Africa and parts of Asia as opposed to Latin America and Eastern Europe, was believed to reduce the risk of the military aligning itself as proponents of reform within the regime or society.

By the same token, scholars such as Alfred Stepan and Juan J. Linz argued that in times of crisis or civil upheaval, sultanism allowed groups aligned with the regime “to capture…a revolution…(as) new leaders, even if they had close links to the regime…[and] advance the claim that the sultan was responsible for all of the evil”49. This happened, for example, in Egypt. Springborg also attributes importance to differences between militaries of republics and monarchies in which the armed forces have less or no stake in the economy as opposed to republican ones. He moreover classified militaries that are dominated by a ruling family, tribe or sect as is/was the case in Libya, Syria, Iraq, Yemen and Sudan50 as products of bunker republics that are “ruled physically or metaphorically from ‘bunkers’” because they “have little if any autonomy from the traditional” social forces that seized control of them at the end of colonial rule.51

Political scientist Omar Ashour identified models of military and security force domination relevant to the Arab world that date back to the 1949 coup in Syria that brought Huns al-Zim to power: an armed institutional racketeering (AIM) model, a sectarian-tribal model, and a less-politicised model.52

Egypt and Algeria exemplify the armed institutional racketeering model. They constitute institutions that see themselves as superior to all other state institutions whether elected or not. That superiority entitles them to perks, privileges and rights, including economic benefits and at least a veto over, if not a decisive say in government policies. Syria, Libya and Yemen represent the sectarian tribal model in which the military is controlled by a specific religious sect and or a tribal coalition, but enjoys the same advantages as in the AIM model. Ashour’s third relevant model existed in Ben Ali’s Tunisia where the military was less politicised and bereft of perks and privileges.

French political scientist Jean-François Daguzan developed a second set of categorisations that also includes Israel. To Daguzan, Israel is an example of a democratic garrison state in which military credentials are a ticket to political leadership. A second category includes militant organisations like Lebanon’s Hezbollah in which religious leaders give license to those perpetrating terrorist acts.

Daguzan puts illiberal democracies like Turkey in which the military was a key political player into a third group and pre-revolt Tunisia in which the autocrat dominated the military into a fourth. He groups progressive authoritarian regimes such as Syria, Algeria and pre-revolt Egypt into a category in which the military is one among several pillars of the regime. Arab monarchies where the military retains its neo-patrimonial role rank on their own and Mauritania with its history of successive coups that stems from its problematic social and political structure symbolises a sixth category.53

U.S. intelligence official William C. Taylor has sought in a detailed study, to analyse Middle Eastern and North African militaries’ responses to civil unrest in terms of their restraints and interests.54 It is an analytical tool that could apply equally to armed forces in Southeast Asia. Taylor’s analysis is rooted in concepts developed by Samuel Huntington, widely viewed as the father of scholarship of civil military relations.55 Huntington initially defined the military’s tendency to interfere in politics to protect its interests as praetorianism, a reference to the Roman emperor’s security that would depose and anoint emperors, and a decade later went further to argue that militaries intervened when ineffective political institutions failed to modernise a country’s political system and economy.56

“In cases where the military enjoyed low restraints and high interests to support the populace (Tunisia), it supported ‘the street,’ whereas in cases where the military operated under high restraints and had low interests in supporting the protesters (Syrian and Bahrain), it supported the regime. Under low restraints and low interests (Egypt), the military reluctantly supported the protesters, and under high interests and high restraints (Libya and Yemen), the military exhibited a fractured response in its support for the regime,” Taylor argued.57

Taylor’s approach explains a military’s immediate response to a crisis but does little to address structural issues such as the Syrian military’s ability to maintain its fighting capabilities despite mass defections or fundamental relationships of distrust between rulers and the armed forces. It assumes that differences only come to the fore at times of popular unrest rather than that they are long- standing and manageable until a crisis erupts. It also does not link interest to the structure of the military, the degree to which its demography is representative of society, and the politics of a regime invested in the armed forces. Scholars Manfred Halpern58 and Lucian Pye59 sought in the 1960s to explain military attitudes towards protests by linking the notion of interests to modernised militaries in former colonies that represented the aspirations of a middle classwith its upgraded technologies and skills. None of these approaches take into account the rise of the security force states in much of the Middle East and North Africa in the decades after Halpern and Pye made their contributions.

Similarly, the degree to which many Arab autocrats allowed their countries to drift in terms of nation- building and social and economic development is evident if one applies the work of late anthropologist Fuad I. Khuri’s. In 1982, Khuri used ethos as the guiding principle of his classification of Middle Eastern militaries that have been overtaken by events.60 Khuri viewed the militaries of Egypt, Turkey and Iran as nation-building organisations. Syria and Morocco were driven by their composition, Syria by their minorities and the Moroccan military by their peasants, while the Gulf and Lebanese militaries were defined by their tribal composition.

A fifth classification by co-author James M. Dorsey divides Arab militaries into six categories according to how an autocrat seeks to neutralise the perceived threat: totally sidelining the military; buying it off with a stake in national security and lucrative economic opportunities; focusing on key units commanded by members of the ruler’s family; creating parallel military organisations; staffing the lower and medium ranks with expatriates; or most recently creating a separate mercenary force.61

Tunisia is in a class of its own, being the only country where the autocrat, Ben Ali, in one of his first moves after coming to power, decimated the military and ensured that unlike the Egyptian armed forces, it had no stake in the system he built. As a result, the Tunisian force had no reason to obstruct real change; indeed, if anything, it was likely to benefit from reform that leads to a democratic system, in which it would have a legitimate role under civilian supervision.

In Egypt, successive military-turned-political leaders secured the loyalty of the armed forces by giving it control of national as opposed to homeland security, allowing it to build a commercial empire of its own and establish an independent relationship with its U.S. counterparts that enabled it to create a military industrial complex, granting it immunity, and shielding it from civilian oversight. Egyptian military attitudes towards the popular revolt against Mubarak as well as Morsi were shaped by a desire to preserve these prerogatives as well as the right to intervene in politics to protect national unity and the secular character of the state. In effect, the military was willing to enter a bargain in which it would neither rule nor governed but at the same time would not be ruled or governed – a deal it ultimately failed to clinch in part because of its political ineptitude.

In Syria, Libya and Yemen, autocratic rulers were able to employ brutal force in attempts to crush revolts because rather than side-lining the military; they had ensured that key units were commanded by members of the ruling family, tribe or sect. That gave those well-trained and well-armed units a vested interest in maintaining the status quo and effectively neutralised the risk and/or fallout of potential defections in times of crisis. It also cemented the family, tribe or sect’s grip on power.

As a result, defections from the Libyan, Syrian and Yemeni military did not significantly weaken the grip of autocratic rulers and their ability to crack down on anti-government protesters. The defections strengthened the protesters and rebels but at least initially did not significantly alter the balance of power. The exception perhaps was Yemen where an attack by a dissident unit on the presidential compound seriously injured President Ali Abdullah Saleh and many of his officials. The attack highlighted the fact that in contrast to Libya and Syria, the split in the Yemeni military had added a new dimension to the crisis in Yemen even though it was launched only after forces loyal to Saleh attacked the unit’s headquarters. The split in the Yemeni military stemmed moreover less from a desire of a wing of the armed forces to promote change but as a result of encouragement by Saudi Arabia that was frustrated with Saleh’s stubborn refusal to step aside. All of this means that such militaries can only be evaluated against the background of fundamental social and economic structures as well as specific political circumstances.

The war in Syria provides a different caveat on the ability of militaries that are built on kinship, tribalism or sectarianism to sustain themselves despite significant defections. Syria’s military after four years of war and defections that reduced its numbers from an estimated 300,000 men in 2011 to 80,000 in 201562 was so weakened by fatigue and a shortage of manpower that it would have to abandon some areas in order to better defend a swath of land from Damascus to Homs and the Alawite coastal area around Latakia.63 The military’s weakness was a result of a prolonged, bitter war and the regime’s sectarian policies. The core of the military, members of Assad’s Alawite sect, were increasingly willing to defend Alawite parts of the country rather than regions populated by other sects that were still under the regime’s control. While defending Damascus, the Syrian capital, and areas adjacent to it was a regime priority, the military became increasingly reluctant to be drawn into urban warfare, which allowed rebels to hold onto suburbs like Jobar.

Bahrain’s military and security forces were able to crush a popular revolt because much of their rank and file is populated by foreigners, mostly Pakistanis. The rulers of Saudi Arabia addressed their distrust of the armed forces by building rival, parallel military organisations; in Iran’s case the controversial Revolutionary Guards Corps and in Saudi Arabia the National Guard now commanded by King Abdullah’s son that operate independently of the armed forces. Similarly, Egypt’s Republican Guard, while a division of the military, was tasked specifically with defending the president. Finally, the United Arab Emirates (UAE) initially invested more than half a billion dollars in the creation of a mercenary force, designed to quell civil unrest in the country as well as in the region. It was forced to disband the force once the contracts were leaked to the media.64

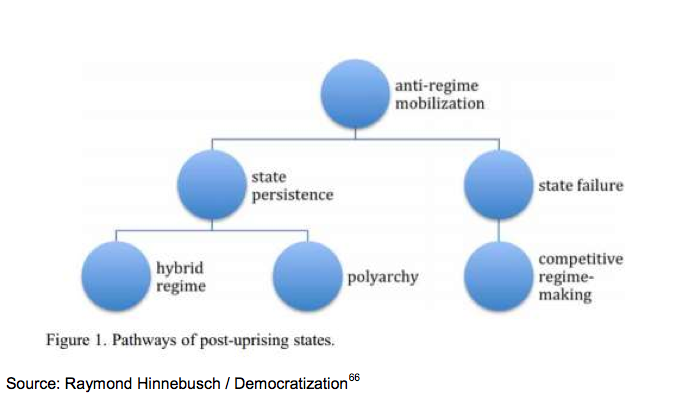

International relations scholar Raymond Hinnebusch’s analysis of responses to popular uprisings in the Middle East and North Africa by regime type is applicable to Dorsey’s classification of the region’s militaries. Hinnebusch argued that state failure in response to popular challenges in the case of Syria, Yemen, and Libya whose militaries were commanded by members of the ruling family, tribe or sect led to a vacuum of authority. By the same token, the challenge did not spark the failure of the state in countries like Egypt whose military was well institutionalised and able to protect its interests or Tunisia where the armed forces had a vested interest in change.65

Dorsey’s focus on the military as a decisive factor in how autocratic regimes respond to popular revolts counter suggestions by some scholars such as Stepan and Linz who argued that the more patrimonial a regime is, the less likely a peaceful transition from autocracy to a more liberal form of governance would be.67 Stepan and Linz reasoned that neo-patrimonial regimes in the terms of scholars Martin Herb68 and Martin Hvidt69 or neo-patriarchal in the definition of Palestinian-American scholar Hisham Sharabi70 that were rooted in Weber’s notion of sultanism were less likely to produce moderates that would align themselves with the opposition. While neo-patriarchy or neo- patrimonialism is one factor that distinguishes Arab autocracies from past dictatorships in Asia, Africa and Latin America, it fails to explain the opportunistic alignment of the military with protesters in Egypt and Tunisia, two countries in which the leader projected himself as a father figure who franchised his authority at different levels of society. In fact, in the words of political scientist Joshua Stacher, it was the centralisation that went along with neo-patriarchy and neo-patrimonialism that enabled the Egyptian military to engineer removal of the leader without endangering the regime as such.71

Hinnebusch effectively took a middle ground position in analysing how neo-patriarchic or neo- patrimonial leaders and their militaries would respond to popular revolts. He wrote, “The capability of neo-patrimonial regimes to resist an uprising over the longer term probably depends on some balance between personal authority and bureaucratic capability. While the personal authority of the president helps contain elite factionalism and his clientalisation of the state apparatus helps minimise defections when it is called upon to use force against protestors, a regime’s ability to resist longer term insurgencies and to stabilise post-uprising regimes requires that the state enjoy institutional and co- optative capability such as infrastructural penetration of society via the bureaucracy and ruling political party.”72 The litmus test for Hinnebusch’s thesis is the escalating insurgency in Egypt’s Sinai.

James Quinlivan’s 1999 summary of steps taken by autocrats to prevent military interventions which he dubbed ‘coup-proofing’ constituted a forerunner to Dorsey’s classification. Measures by autocrats cited by Quinlivan were designed to keep the military pre-occupied or off-balance and/or co-opt it. They included: placement of loyal family, ethnic or religious associates in critical government and military positions, creation of an armed force in parallel with the regular military, establishment of competing security and intelligence agencies with overlapping jurisdictions, professionalisation of the regular military and generous state funding.73

Political scientist Federico Battera provides a theoretical framework for Dorsey’s classification arguing that the strength of the interrelationship or degree of fusion between the state machinery, the party in power, the military and the security forces determines a Middle Eastern or North African regime’s sustainability and the response of the armed forces to popular unrest.74 Battera’s concept of fusion constitutes an attempt to fine-tune fellow political scientist Johannes Gerschweski’s notion of intra- elite cohesion75 in a bid to operationalise interconnections. Battera wrote, “Where fusion was evident, transition towards democracy proved difficult and the only way out seemed to be…a dramatic regime change.”76 Indeed, Tunisia like Indonesia, the Philippines and Myanmar were examples of a lack of fusion that drove the interest of the military or significant elements of the armed forces in regime change rather than defense of the status quo or a simple replacement of the leader as in the case of Egypt.

Focusing Middle Eastern and North African militaries on national rather than homeland security often allowed autocrats to remove the armed forces from politics, a process that according to Hazem Kandil, began in the immediate aftermath of the 1967 Six-Day War.77 Some analysts argue that Egypt’s leaders – Gamal Abdel Nasser, Anwar Sadat and Mubarak –started favoring the state security apparatus over the military as a tool of repression and political control in 1952 shortly after the toppling of the monarchy. An exception to the near consensus on the discussion of the military versus the security state is Yezid Sayigh, who argues that Egypt continued to be a military state, but that what changed was the visibility of the military within the Egyptian political and economic spheres.78 Sayigh’s thesis appeared to be validated in the overthrow of Morsi and the military’s role in the shaping of post-Morsi Egypt even though the security forces played a major role in persuading the armed forces of the need for intervention.79

Retired Egyptian general Mohamed Shousha reasoned that the military sees its role as the ultimate arbiter in politics. The threat of intervention was designed to keep “all the elements on the political scene…on the right track in order to keep the military from intervening. It’s a kind of mental deterrence,” he said.80 The military defined national security as going beyond guarding territorial integrity and against foreign intervention to include policies that threatened to derail the economy. This definition was grounded in the military’s growing commercial interests and the increased role of retired military personnel in non-military government institutions. The military’s broad definition of national security resembled the rise of Tunisia’s ousted president, Ben Ali, who came to power in 1987 pledging liberalisation and democratisation only to target Islamists and repress his political opponents several years later.

Transition in much of the Middle East and North Africa from reliance on the military to a security force involved the evolution from what Eric Nordlinger termed the ruler type of military regime in which the armed forces controlled government and the political process for a longer period of time, to the moderator type in which it exercises veto power over civilian governments but refrains from holding political office.81 The favoring of university graduates as junior officers and Sadat’s firing and sidelining of senior officers cemented the Egyptian military’s subordination to a president who looked to the security forces to ensure domestic control. The military’s allegiance to Sadat was demonstrated when in 1977 it crushed mass protests sparked by rising prices as a result of an International Monetary Fund (IMF)-backed cut in subsidies. It was under Mubarak, however, that the military finally saw one of its core interests, economic dominance, challenged with the emergence of new elites that became the core of the ruling class. That class threatened to further marginalise the military despite the fact that top military officers were part of the president’s corrupt system.

Mubarak relied on the military in the wake of the Sadat assassination and again in 1986 when the Central Security Forces (CSF) established in 1977 in the wake of food riots – the most serious popular uprising against the Egyptian regime since the 1952 coup. The CSF was Mubarak’s effort to counterbalance the military even though it was more susceptible to Islamist influences because its members were poorly armed and paid. Mubarak dismissed 20,000 CSF personnel in the wake of a mutiny on suspicion that they were Islamists. Al Sisi sought to assert his primacy over the security forces in the wake of Morsi’s deposal by ensuring that in the military-guided government appointed to succeed the elected president a general, Muhammad Ibrahim and his replacement in March 2015, retired general Magdy Abdel Ghaffar, controlled the interior ministry to which the police and Central Security Forces (CSF) reported. The military nonetheless was dependent on the security forces that functioned like in Mubarak’s days as the repressive face of the regime. For all practical matters, the military acceded to long-standing demands by the police and security forces for more firearms, looser rules of engagement, and legal protection from prosecution.

In fact, Egypt raises the question whether it is the dog wagging its tail or the tail wagging the dog despite the fact that relations between Arab militaries and security forces are often strained. Accounts by Egyptian interior ministry officials and security force and police officers of their role in undermining Morsi during his year in office, helping organise the widespread anti-Brotherhood protests, and persuading the military to topple the president suggest that Mubarak’s favouring of the security sector has had a fundamental impact on the balance of forces in Egypt.82 The officials and officers date their determination to oppose what they saw as a threat to the country to a series of jail breaks in late January 2011 during the anti-Mubarak protests when Morsi and scores of other Muslim Brothers escaped prison. Some 200 police officials were killed in the prison breaks. They said that they identified and encouraged activists unhappy with Morsi’s rule to organise mass protests against the president and were instrumental in drafting and distributing a petition that was signed by millions demanding Morsi’s resignation. The campaign culminated in millions on congregating on Tahrir Square in late June 2013 and the military coup in early July. In Daguzan’s view an alliance between militaries and oligarchic elites as has emerged in post-Morsi in Egypt constitute a likely phase in the Middle East and North Africa’s drawn out, messy and convolute transition from autocracy to greater transparency and accountability.83

The fact that Arab militaries unlike their Southeast Asian counterparts failed to engage with forces of change in any serious manner resulted in what Stacher termed “the militarisation of politics and societies”84 that led to increased state violence and a qualitative change in relations between the state and significant segments of society. Militarisation was the armed forces’ response to the fragmentation of the state and the breakdown of long-standing governance as a result of the popular revolts. The breakdown enabled militaries and security forces to fill the void, Stacher argued.85

“Rather than consent to a transition, counter-revolutionary agents conspired with transnational partners and capital to block popular empowerment by building new authoritarian regimes out of the remains of what had previously existed… Rather than bend towards the popular will and open up the politics as citizen mobilisation demanded, the surviving elites militarised and reconfigured regimes from parts of what previously existed. In some other cases the collapse of regimes put the state itself at risk and left a vacuum in which authority became contested. Both outcomes obstructed democratisation but did not mean a return to the days of pre-revolutionary authoritarianism. Rather, it was regime-making.,” Stacher said.86 Increased repression served that purpose.

Rebuilding relations with the military was key to the effort by the police and security forces that was initiated within weeks of Mubarak’s downfall and gathered pace when Morsi became in July 2012 Egypt’s first democratically elected president. They said Morsi’s effort to gain control of the interior ministry by replacing Ahmad Gamal with Mohammed Ibrahim who he saw as less opposed to the Brotherhood backfired and proved to be a fatal mistake. Ibrahim sought to forge ties to Al-Sisi by attending events in which the general participated and showered him with praise. Ibrahim’s efforts led to regular meetings in the first half of 2013 between security force and military officials to discuss the course the Brotherhood was charting for Egypt, including what they saw as plans to restructure the interior ministry that would have significantly weakened the security forces. A security force officer who participated in the meetings commented, “I have gone to some of those meetings with the army and we spoke a lot about the Muslim Brotherhood. We had more experience with them then the army. We shared those experiences and the army became more and more convinced that those people have to go and are bad for Egypt.”87 The security forces put their imprint on the post-Morsi crackdown on the Brotherhood when they ignored military plans in August 2013 to evacuate Raba’a al Adawiya Square where thousands of pro-Morsi demonstrators had been camped out for weeks that were designed to minimalise casualties by issuing warnings and using water cannons. Instead, the security forces employed teargas, live ammunition and bulldozers. Hundreds were killed and many more died in clashes that erupted across the country after the raid.

The Egyptian experience and the various models for Middle Eastern and North African militaries, irrespective of how one categorises them, highlight the need for military and security sector reform as a key factor in the transition from autocratic to more transparent and accountable political structures. The complexity involved in reform are obvious in the experience of countries like Indonesia, the Philippines and Turkey that have struggled for years with changing a culture of impunity pervasive throughout the military and security sector and highlight issues that go beyond upholding human rights. The implementation of reforms also explains why Southeast Asian political transition was relatively successful while Middle Eastern and North African nations with the exception of Tunisia have experienced setbacks.

Asserting full civilian control of the military in Indonesia and Turkey was and is a long-drawn out process that has complicated the ability of the state to establish itself as a catalyst of democratic rule. Those issues came to the fore when heavily armed Special Forces raided an Indonesian prison and summary execution of four inmates in 2013, 15 years after the end of autocratic rule. The raid and subsequent charging of 11 officers, one of several incidents involving security forces, sparked debate about the nature and terms of the reform including the fact that members of the Indonesian armed forces were accountable to military rather than civilian courts. These courts proved to be lenient in sentencing soldiers accused of murder.

Critics blamed the incidents on the failure to reform the internal workings and culture of the armed forces. At the center of the debate lay questions that were certain to be raised in Middle Eastern nations where the alleged impartiality of the armed forces is under fire. Leaks of a report of a fact- finding mission established by Morsi asserted that the military had killed and tortured protesters during and after the revolt against Mubarak – charges the command of the armed forces denied.

Parallel systems of justice in various Arab nations also impinged on the rule of law. Lack of full civilian control in Egypt fueled the continued existence beyond the law of a deep state – a network of vested political, military and business interests – similar to the one in Turkey that took decades to uproot and threatened political and economic change demanded by the European Union. The Turkish military’s vested economic interests distorted economies because of fiscal concessions and access to inside information.

The debate in Indonesia sparked by the incidents focused on the same issues confronting post-revolt Arab nations like Egypt, foremost among was the kind of reform that is needed to adapt the military and security forces to a democratic society; also whether non-transparent military courts were able and willing to maintain accepted human rights standards. A decade-and-a-half of democracy and free media enabled Indonesia to publicly debate the effectiveness of past reforms. That debate has been stifled and erupted in protests on the streets of Egyptian cities as the military reverted post-Morsi Egypt to Mubarak style repression, planting the seeds for yet more dissent and volatility. The contrast in responses to incidents by the Indonesian and Egyptian militaries were telling: the Indonesian military reacted to the raid by relieving the military commander of Central Java of his duty for initially denying that Special Forces had been involved. For its part, Egypt’s Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (SCAF) warned against efforts to tarnish the military’s image, cracked down on opposition forces and the media, and allowed courts to sentence teenage and other protesters to lengthy prison terms.

Yet, like in Indonesia where the 11 officers experienced a wave of support because their victims were alleged drug traffickers, efforts to reform the military in Egypt were complicated by a divided public, a significant part of which believed that military-backed rule was their country’s only way out of its crisis.

Indonesia’s lesson for the Middle East and North Africa is that given the structure and nature of Arab militaries and security forces, reform will have to entail not only guaranteeing in some cases that their rank and file is representative of a country’s demographics but also revisions of internal procedures, ethical standards, education, training and compensation. Such reforms go far beyond replacing military commanders as Morsi did in 2012 or the dismissal by Yemeni President Abd Rabbuh Mansur al-Hadi of senior officers related to the country’s ousted leader, Ali Abdullah Saleh. Those moves were largely motivated by the two men’s efforts to employ the military as tools to stabilise their grip on power.

They are like much of the positioning of the military in various Middle Eastern and North African nations traceable to the playbook of Nasser and Abd al-Karim Qasim, the Iraqi general who came to power in a coup in 1958: the mobilisation of supporters on the streets, the tacit endorsement of vigilante groups among the population to target the enemy, and the push for control of all major squares and public spaces.

Cairo’s Tahrir Square, traditionally a military parade ground, served, for example, as the gathering point for the masses demanding that Nasser remain in office despite Israel’s crushing defeat of the Egyptian military in 1967. The 2011 uprising against Mubarak put Tahrir’s historic significance to bed and revived it as the focal point of contentious street politics. Efforts by the military government that succeeded Mubarak to put a stop to the square’s role as a venue for expression of political dissent failed: it remained a gathering point for opponents of the military for the 17 months it was in government.

In Egypt, an insurgency in the Sinai contributed to the military’s success in exploiting popular anti-Brotherhood sentiment to achieve public acceptance of repressive policies, the revival of the coercive state and prevalence for security rather than political solutions for political problems. It did so through a combination of demonisation of the Brotherhood as a terrorist organisation reinforced by a campaign in dominant media that were either state-owned or co-opted. The penchant for security solutions served as evidence that the military understood that its projection of itself as the executor of popular will as well as its perceived support for the overthrow of Mubarak was conditional.

That conditionality was long evident in popular responses to decades of battlefield failure and the rise in the 1970s and 1980s of Islamist movements, some of which as in the cases of Lebanon’s Hezbollah and Palestine’s Hamas were feted for their resilience and resistance to Israel. The militaries’ dilemma was brought into sharp focus by the rulers’ expectations that they would ruthlessly counter the Islamist threat in exchange for the regime ensuring public acceptance of the militaries’ legitimacy and continued international support.88

The dilemma was further highlighted with the credibility of autocratic regimes and Arab militaries repeatedly being called into question in the decades preceding the 2011 Arab Spring despite the fact that civil society and significant segments of the population did not immediately rise up. Nevertheless, increasing popular discontent and lack of confidence in militaries that had failed to perform in virtually every conflict in the region, including Lebanon, Iraq and Palestine was evident in that period in this author’s scores of interviews and private conversations across the Middle East and North Africa. Hezbollah was credited with forcing Israel to withdraw from southern Lebanon in 2000 and Hamas with Israel’s disengagement from Gaza in 2005, not Arab militaries who were increasingly perceived as subservient to the U.S. because of their dependence on U.S. weapons, adoption of U.S. military doctrine and reliance on U.S. training.

Criticism became increasingly public with the emergence of social media. Critics mocked the incompetence of Western-backed Arabs. Some derided senior officers as fat and lazy.89 Others compared them to women’s makeup.90 In the conspiratorial world of the Middle East, U.S. military aid was depicted as designed to turn Arab militaries into agents of U.S. policy rather than defenders of Arab nations.91

That perception gained currency with Egyptian and Jordanian militaries’ acceptance of their governments’ peace treaties with Israel and growing cooperation between Israel and various Arab states with Saudi Arabia to counter the rise of Islamists and of Iran in the region. Debates on the Internet and in some media often discussed whether Arab militaries were making way for unconventional, popular resistance forces in Lebanon, Gaza and Iraq that were proving to be far more effective92 and turning their guns on their populations in an effort to preserve their perks and privileges.93 Discussions about and perceptions of Arab militaries have become more polarised with the post-Arab Spring eruption of wars in Syria, Libya, Yemen and Iraq that have divided countries and societies.

Moreover, Arab militaries are increasingly seen as burdens to budgets, incompetent businessmen and protectors of repressive rulers. That view, evident in opposition media and on the Internet, gained significant currency with the collapse of the Iraqi military in 200394 during the U.S. invasion and again in 2014 when the Islamic State captured swathes of northern Iraq, including Mosul, the country’s second largest city.

David and Bark noted, “In contrast to the state-controlled media in most Arab states (except Lebanon and some Gulf monarchies), which extols the performance of the Arab militaries, the New Arab Media provides fresh opportunities for criticising these institutions, which for decades were considered a taboo subject in the Arab public sphere… Arab militaries are forced to engage in a constant struggle to preserve their reputation and legitimacy and that at least some of them know when it is better to swallow their pride. The debates waged during these periods of regional crisis over the management of military issues in the Arab states also reveal the extent of the public’s alienation from the military.”95

A satirical poem by Egyptian poet Muhammad Bahjat* aired in 2006 on a popular TV show during Israel’s war against Hezbollah went viral on social media and was often repeated in protests that led up to the 2011 revolts.96

One, Two,

The Arab army where are you?

The Arab army where are you?

The Egyptian Arab Army resides in an-Nasr compound Wakes up in the afternoon to drink its tea

The Gulf Arab army can do absolutely nothing Strategic silence indeed

Cut us some slack, man!

The Tunisian Arab army is green like parsley

But ‘Aziza loves Yunis

The wars can wait

The Sudanese Arab army

I can hear its clamor in my ears

Damn it! Am I alone in battle?!

Come on, Abu Hussein, let’s leave!

One, Two,

The Arab army where are you?

The Arab army was humiliated when the Afghans were attacked By its long silence in Bosnia

And when it started deepening the public debt.

The jury is still out on whether Saudi and UAE-led intervention in Yemen will reverse the notion of Arab militaries as parasitic failures. Despite the Gulf alliance’s advances against the Houthis, it is too early to pass judgment on whether the performance of Arab militaries has entered a new era. In the short-term, it has boosted a sense of national pride and unity in Gulf countries. Yet, the fight against the Houthis retains the potential of becoming the region’s Vietnam in which Gulf troops are dragged into a costly and lengthy guerrilla war. In addition, a protracted bombing campaign that preceded the introduction of Gulf ground troops has devastated Yemen, the region’s poorest country, and deepened anti-Saudi sentiments. These sentiments could increase if expectations for a post-war reconstruction process that would take years and cost billions of dollars are not met.

The long-term impact of the rise of pride and unity in the Gulf that builds on the recent introduction of conscription in countries like the Qatar and the UAE remain to be seen. UAE conscripts barely a year into compulsory service have suffered their first casualties in Yemen. The deaths have sparked a sense of national purpose97 but left grieving families in shock and angry. “These young men are forced to do military service and should not be taken to hot conflict areas. They are civilians who are supposed to go back to their lives and work after finishing their service,” Middle East Eye quoted an Emirati as saying.98

Similarly, Egypt’s military performance against Bedouin and jihadi insurgents in the Sinai desert and mounting political violence has escalated the conflict with no end in sight. In addition, the closing off of all public spaces and relentless repression of all dissent by the military-backed government of Al Sisi is driving radicalisation among youth disillusioned by the failure of the 2011 revolt that toppled Mubarak and whose already dismal economic and social prospects have deteriorated further.

Southeast Asian Assets the Middle East and North Africa Lacks

An analysis of Middle Eastern and North African militaries has produced a laundry list of literature much of which was either valid for a specific period of post-World War II literature or highlighted one of more aspects of military interest in the status quo or attitudes towards political change. Leaving aside the geopolitical differences between Southeast Asia and the Middle East and North Africa, a comparison of transition in the two regions brings into sharp focus building blocks that are needed for an armed force to embrace change. Southeast Asian nations succeeded where Middle Eastern and North African countries with the exception of Tunisia, has failed for several reasons.

Southeast Asian militaries were reflections of their countries demography, which many Middle Eastern and North African militaries are not. Southeast Asian autocrats like former presidents Markos and Suharto sowed the seeds of their demise with divide-and-rule policies that disadvantaged significant elements of their militaries. By contrast, Middle Eastern and North African autocrats were able to by and large ensure the commitment of their militaries, irrespective of their demographic composition, to the regime, if not the leader, by ensuring that they had a political and in many cases also an economic stake in the system.

Southeast Asian autocracies, despite repression, boasted a far more resilient civil society with whom reform-minded military personnel could partner with, than did Middle Eastern and North African ones. A comparison of donor policies in both regions that goes beyond the immediate parameters of this study would contribute to understanding why Southeast Asia was able to develop a relatively robust, even if clandestine civil society network, that has yet to emerge in the Middle East and North Africa. One further explanation for Southeast Asia’s success as opposed to the messy, bloody, violent and at times retrograde experience of transition and militaries’ counterrevolutionary approach lies in the fact that no one or sub-group of regional powers sought irrespective of cost to influence the outcome of transition elsewhere in the region. Similarly, transition in Southeast Asia and the role of external powers did not produce the likes of jihadist groups such as the Islamic State. The emergence of the Islamic State served as a lightning rod which either shifted the focus of political battles for change that were being waged or undermined Western support for change in the long disproven belief that support for autocratic regimes constituted the best formula to shield homelands and key regional allies from political violence and changes that would produce regimes far more hostile to their interests.

It is a policy that is pregnant with risk and bound to give birth to failure. Middle Eastern and North African militaries, unlike their far less tested Southeast Asian counterparts, have largely failed when challenged on the battlefield. Gulf intervention in Yemen has so far produced death and destruction, without the promise of a sustainable political solution to the crisis. Airstrikes like those of the U.S. against Islamic State targets in Syria and Iraq have at best been pin pricks that have hardly put a dent in the jihadist group’s control of territory or ability to strike back. All in all, Middle Eastern and North African military failure has produced unconventional forces whose performances put that of conventional militaries to shame.

Conclusion

While Southeast Asian militaries play a complex and at times still problematic but nonetheless purely political role in the deepening of democratic change, Middle Eastern and North African ones will likely continue to be counterrevolutionary forces that do not shy away from violence and brutality to stymie reform or ensure that it is at best cosmetic. To redraw the picture, Western nations with the U.S. in the lead would have to adopt a robust medium-term approach that sees political change as the best guarantee of security and long-term stability at the cost of short-term setbacks. Only that kind of approach holds out the promise that Middle Eastern and North African nations can acquire the building blocks that facilitated transition in Southeast Asia.

It is an approach that has become riskier in a multi-polar world in which countries like Russia and China would be willing to fill perceived vacuums that would emerge as a result of a major Western policy shift. The risk is mitigated by the fact that third powers seeking to exploit short-term consequences of a U.S. and Western policy shift are unlikely to succeed where the West failed, and make themselves far greater targets than they already are of militant groups.