Ghost Ships And Off-Target Cruise Missiles – Analysis

By Published by the Foreign Policy Research Institute

By Lawrence Husick*

(FPRI) — “A maritime incident has been reported in the Black Sea in the vicinity of position 44-15.7N, 037-32.9E on June 22, 2017 at 0710 GMT. This incident has not been confirmed. The nature of the incident is reported as GPS interference. Exercise caution when transiting this area.” – United States Maritime Administration

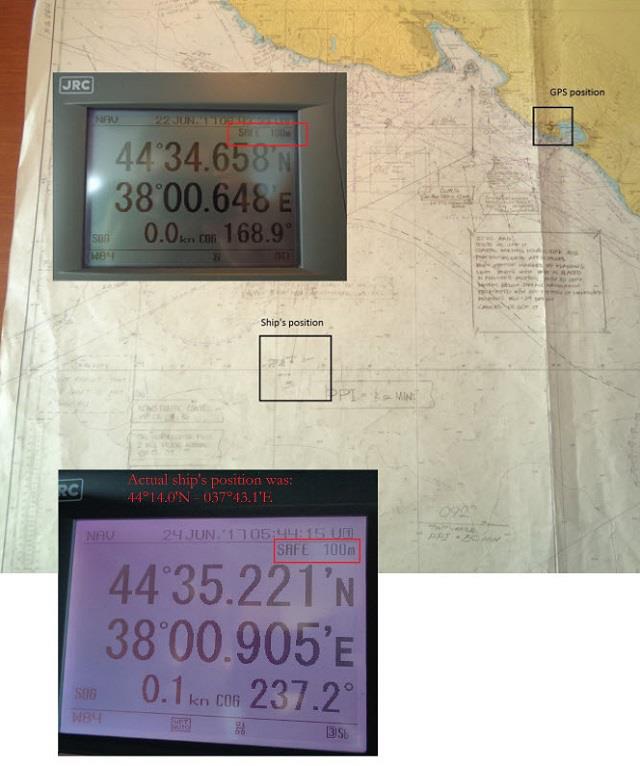

This report originated from the captain of a U.S. merchant vessel in the Black Sea, who reported to the Coast Guard Navigation Center, “GPS equipment unable to obtain GPS signal intermittently since nearing coast of Novorossiysk, Russia. Now displays HDOP 0.8 accuracy within 100m, but given location is actually 25 nautical miles off; . . . I confirm all ships in the area (more than 20 ships) have the same problem.”

The captain sent along the following photo:

In February 2010, FPRI published an E-Note, “Avoiding a Homeland Security Error That Could Leave the U.S. Flying Blind,” that discussed the termination of the United States’ LORAN terrestrial radio-frequency navigation systems. The justification for that decision was that shuttering the broadcasting stations would save approximately $36 million per year. This author argued that LORAN-C stations should have been retained, and upgraded to eLORAN (a newer digital version that is more robust than the older system), if only to serve as a backup to the satellite-based GPS system. At that time, we stated,

Some reasons given include the use of Loran as a reliable backup for GPS, which is prone to interference and possible system degradation and failure; use of Loran to augment GPS for better operational reliability and accuracy in the Continental United States; use of Loran as an alternative timing source for transportation and communications systems including cellular telephone systems that fail without time synchronization; and global leadership and cooperation with allies in providing maritime navigation and safety systems.

In 2014, the U.S. Government recognized its mistake in destroying the LORAN system, and a bill authorizing eLORAN was passed. The Coast Guard Authorization Act of 2017 (H.R. 2518/S. 1129) includes authorization to implement eLORAN. The current bill requires that eLORAN be operational three years after the passage of the act. Today, three years after first authorization, however, the eLORAN system remains on the drawing board, and no actual implementation has taken place.

While the origin of the degraded GPS signals in the Black Sea is, at this time, unknown, it is likely that it is related to Russia’s deployment of over 250,000 GPS jamming transmitters on cell towers throughout the country. The October 2016 issue of OEWatch explained, “The Russian Ministry of Defense has accepted into the inventory the Pole-21 radio suppression system, which defends Russian strategic facilities from enemy cruise missiles, guided bombs, and unmanned aerial vehicles, which use the GPS . . . satellite systems for navigation and guidance to the target. The latest jammer . . . covers entire regions like a dome that is impenetrable for satellite navigation signals.”

In his May 11, 2017 testimony before the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, Director of National Intelligence Daniel R. Coats said, “The global threat of electronic warfare (EW) attacks against space systems will expand in the coming years in both number and types of weapons. Development very likely will focus on jamming capabilities against dedicated military satellite communications (SATCOM), Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) imaging satellites, and enhanced capabilities against Global Navigation Satellite Systems (GNSS), such as the U.S. Global Positioning System (GPS).”

While incorrect navigation of twenty merchant ships in the Black Sea may not seem significant, the United States and its allies face a larger issue: the effectiveness of Russian countermeasures that effectively blinds our “smart” weapons and disrupts the flow of positioning information that is vital to U.S. information superiority. Such jamming technology dates back to at least 1997, when a Russian firm first showed a small portable GPS jammer at the MAKS airshow near Moscow.

As reported by the SpaceDaily website, “At the start of the 2003 US-led invasion of Iraq not a single cruise missile was able to hit its target. Five days and dozens of lost cruise missiles later the Americans accused Russia of redirecting the Tomahawks towards the desert away from their designated targets. Only after the Americans had located the positions of the Russian jammers and destroyed them in a series of carpet bombing raids, did the Tomahawks manage to regain their smart capabilities.”

The U.S. Army, meanwhile, has acknowledged that it is losing the electronic warfare (EW) race to Russia. Only 813 soldiers (out of over 500,000 on active duty) are trained in EW, and there are only 1,000 positions authorized service-wide. Equipment lags, as well, with U.S. forces unable to match the newly deployed Krasukha-4 jammer now deployed in Ukraine and Syria. According to Ronald Pontius, deputy to Army Cyber Command’s chief, Lt. Gen. Edward Cardon, “you can’t but come to the conclusion that we’re not making progress at the pace the threat demands.”

Seven years ago, FPRI pointed out that a single, obscure 30-year old navigation system was being decommissioned to save a relatively insignificant sum of money, but that having a backup for GPS was the wiser course of action. Writing about the recent incident in the Black Sea, Dana A. Goward, President of the Resilient Navigation and Timing Foundation said, “Assuming Russia is behind this, why would they do such a thing? Maybe it was to encourage use of the Russian GLONASS satellite navigation system or their terrestrial Loran system, called Chayka, instead of GPS. Perhaps it was for some security reason known only to them.”

The U.S. Coast Guard, in a January 2016 safety alert about jammed GPS signals that affected freighters and tankers, gave what may be the best advice about relying on GPS for navigation. Echoing Ronald Reagan, the Coast Guard advised, “Trust, but verify.” For most of us, this advice may mean keeping a paper map in the car. For ships at sea, it means having personnel aboard who know how to use a sextant, chronometer, and sight reduction tables to conduct celestial navigation. For the warfighter depending on smart weapons in a high paced engagement, there may be no fallback from which to easily verify. Regardless, the lesson may be that when it comes to navigation and electronic warfare systems, the U.S. can ill-afford shooting itself in the foot for dubious budgetary reasons.

About the author:

*Lawrence Husick is Co-Chairman of the Foreign Policy Research Institute’s Center for the Study of Terrorism. He is also co-director of the FPRI Wachman Center’s Program on Teaching Innovation and a faculty member at the Whiting Graduate School of Engineering and the Krieger School of Arts and Sciences Graduate Biotechnology Program of the Johns Hopkins University.

Source:

This article was published by FPRI.