Dutch Disease: Cause Of Africa’s Rising External Debt – Analysis

By Observer Research Foundation

By Rahul Mazumdar

External Debt

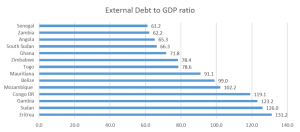

Public debt levels have been rising across regions, but it is more of a concern in Sub-Saharan Africa. After almost 10 years when Africa benefitted from the World Bank and International Monetary Fund’s Heavily Indebted Poor Countries initiative, the debt burden may once again haunt some of the economies in Africa. Of the 39 countries eligible or potentially eligible for HIPC Initiative assistance, 30 are in Africa itself, with 9 of these economies appearing amongst the top 15 in terms of debt to GDP in the region.

A relatively recent Article IV assessment conducted by the IMF in January 2018, provides some crucial insights. The debt sustainability analysis finds that out of 23 countries which are at a high risk of debt distress, almost a dozen are in Africa alone. Some of them being, Burundi, Cameroon, Central Africa Republic, Djibouti, Gambia, Ghana, Mauritania, and Zambia, amongst others. The IMF suggests that sovereign debts above 40% of the country’s GDP in developing and less –developed countries may increase chances against sustainable development.

Given the fact that it becomes expensive to borrow locally, as the interest rates are on the higher side in Sub-Saharan economies, accessing overseas at a relatively lower rates becomes lucrative for them. This has been the primary reason for Sub-Saharan economies to get into this burden of external debt.

Given the appetite for debt in the region, the external borrowing position of these economies in Sub-Saharan Africa has experienced a linear increase, with debt levels touching an all-time high of USD 454 billion in 2017. While the external debt situation worsens, the gross debt to GDP ratio of the region appears equally worrying. According to the latest IMF data, the figure has increased from 30 per cent in 2008 to 54 per cent in 2017.

To some, these ratios may not be of a concern when compared to western economies, which are equally if not more culpable to such high debt figures. A higher debt-to-GDP ratio would have perhaps been acceptable, if the economy would have been growing rapidly, which would allow future earnings to pay off the debt. Unfortunately this is not the case with the economies in Sub-Saharan Africa as most struggle to utilize the debt judiciously within the time frame. Besides this there is hardly any capital market which could sustain their local demand.

Coupled with this is the fragile public revenue collection in the region, which makes servicing the external debt further difficult. Alternatively raising taxes could be possible, but that would be detrimental to the existing growth of the economy. Corporate tax increase would also essentially be a drag on the existing investment scenario. At times, many a concessional financing offered to Africa are in lieu of FDI wherein investors are allowed duty-free imports on capital equipment, and in the process governments are denied the much needed tax revenue in foreign currency.

Huge borrowings in foreign currencies also exposes these economies in the region to exchange rate risks. With 61 per cent of borrowings in dollar terms, depreciation of the local currencies in the region is but natural. It may be noted that reserves to external debt stock has already experienced a significant decline in Sub-Saharan economies from 66.5% in 2008 to 30.8% in 2016.

Dutch disease syndrome

Africa in general and Sub-Sahara in particular is not new to this phenomenon of high external debt. The Dutch disease syndrome, a natural resource curse, is largely responsible for this debt burden. Given Africa’s substantial dependency on natural resource, the region succumbs to volatility in commodity prices easily. With commodity prices on a decline the foreign exchange coffers dries up.

As oil exporters many of these economies in the region are at the whims and fancies of global demand and supply of oil. The oil prices plummeted from a high of US$ 120 in 2013 to gradually touching a low of US$ 30 in 2016. There is a recent spurt in price, but the longevity of it remains unpredictable, and may not be enough to pull these economies out of this debt. The dependency on commodities gets more aggravated in economies which are also doubling up as producers and exporters of agricultural goods and metals.

New debt instruments

It may be noted that African economies are increasingly exposing themselves to commercial loans which have a shorter tenor, fewer concessional terms, and are issued at times in foreign currency as in Yuan, exposing these vulnerable economies to exchange fluctuations. Some of the economies have also started issuing Sukuk bonds, which are favoured in Islamic countries, and have an increasing West African presence, including in Senegal, Ivory Coast, Togo, South Africa and Nigeria. These instruments are largely not under the purview of multilateral rules and regulations, and hence have to be handled independently by the recipient countries incase of any eventuality.

There are also reports wherein Chinese have extended credit to many economies, including in Africa, which are not transparent according to IMF and World Bank, leading them to offer China to join the Paris Club. Paris Club is a group of creditors that specialises in loans to governments and requires both its members and their debtors to adhere to transparency standards.

At the same time, for these nations to be able to pay back their bond issuances, they need to use their proceeds in high-return investments. Directing these funds to projects that do not make revenue will only effect in additional pressure when repaying the bonds.

Depreciation currency

Amidst increasing debt, is the depreciation of the exchange rates of the African economies against the dollar which is a cause of concern as well. The depreciation of the local currency results in more money needed to pay for the debt. Rand depreciated by as much as 11% in the last three months, while the CFA franc depreciated by around 5% in the last 3 months. CFA franc is the currencies of Cameroon, Central African Republic, Chad, Republic of the Congo, Equatorial Guinea and Gabon.

Possible cure

Possible cure to the rising external debt? Answer perhaps is none in the immediate term. Opportunities in the continent is phenomenal – and they are perhaps the last frontiers in the global economy which can show double digit growth if the hands meet the mouth.

While it is reasonable that the government would welcome external financing to support infrastructure development, it is imperative to assume a realistic approach keeping the above-mentioned factors in mind. For now, the least the authorities can do is to strengthen efforts to scale up revenue generation in a bid to keep public debt at a sustainable level. Governments in the region have be prudent in attending to their fiscal responsibilities while widening the scope to raise taxes. Simultaneously, a sustainable industrial development would be required across these economies to raise domestic revenues.

Alternatively, these countries, instead should look at PPP model of infrastructure development to generate cash flows to repay their borrowings, whilst making their debt sustainable.

Last but not the least, to combat the Dutch disease which is incessantly becoming cancerous to the economies in the region, it is important for sovereigns to set time frames towards diversifying their economies away from commodity led export earnings. Widening the export basket will be a huge panacea to most of the problems in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Unless appropriate forward looking steps are taken, Sub-Saharan Africa will continue to intermittently remain under the garb of external debt.