The Innovation Dilemma – Analysis

US-Chinese tensions are less about chronic trade imbalances and more about worries over strategic innovation.

By Stephen S. Roach*

Sino-American tensions are less about trade imbalances and more about a strategic clash over innovation and technology — the Holy Grail of any nation’s prosperity. The large and seemingly chronic trade imbalance between the United States and China is as much a function of America’s own macroeconomic problems as a reflection of unfair Chinese trading practices long alleged by the Washington Consensus and now underscored by the Trump administration.

The United States suffers from a chronic deficiency of domestic saving. Its net national saving rate was just 3 percent in the first half of 2018 — up from the 1.9 percent post-crisis average since 2009, but still less than half the 6.3 percent norm of the final three decades of the 20th century. Lacking in saving and wanting to invest and grow, the United States must import surplus savings from abroad and run massive current-account and trade deficits to attract foreign capital.

Therein lies Trump’s folly. The United States had trade deficits with 102 nations in 2017 — a multilateral problem. By opting for budget-busting tax cuts in late 2017, America’s already depressed domestic saving will move sharply lower in the years ahead, pushing its current-account and trade gaps deeper into deficit. Moves to rectify this imbalance with tariffs against China will only backfire. The Chinese piece of the trade deficit is already shifting to higher-cost trading partners, putting more pressure on American consumers. There is no bilateral fix for a multilateral problem.

Trade deficits are a foil for a more profound struggle between the United States and China. A White House policy paper says it all: “…the Chinese State seeks to access the crown jewels of American technology and intellectual property.” White House advisor Peter Navarro adds, “China has targeted America’s industries of the future … if China successfully captures these emerging industries, America will have no economic future.”

These charges draw heavily on the March findings of a so-called Section 301 investigation conducted by the US trade representative, Robert Lighthizer, a report which has become central to Washington’s anti-China narrative. The conclusions are wide of the mark in four areas:

Joint ventures: Allegations of forced technology transfers through the JV structure overlook the most basic aspect of these arrangements — two partners working together willingly, in the context of commercially and legally binding agreements, to create a business that requires sharing of personnel, systems and processes.

Cyberhacking: Presidents Barack Obama and Xi Jinping addressed allegations of cyberhacking during the 2015 Sunnylands Summit. Since then, cyber incursions have been sharply reduced, a point overlooked by the US trade representative in its emphasis on cyberhacking activity that largely predates the summit.

Outbound capture: The US trade representative charges China with technology theft through its policies of acquiring US companies and their proprietary systems. Yet tabulations by the American Enterprise Institute find that only 16 of China’s 228 outward bound M&A deals over the decade ending in 2017 were in the technology sector.

Industrial policy: The US trade representative insists that China is unique in using industrial policies, such as Made in China 2025 or AI 2030, to gain an unfair advantage in the acquisition of foreign technology. However, from Japan to Germany to Pentagon-sponsored innovations of America’s military-industrial complex, industrial policies have been more the rule than the exception for today’s leading economies.

These allegations imply the Chinese have no rightful claim to the hallowed ground of innovation that has long defined the prosperity of nations. That overlooks the simple fact that ancient China was the world’s preeminent innovator – from agricultural production to textile weaving, from paper and printing to missiles and gunpowder. Also ignored is a long history of flagrant examples of technology theft in the 19th century by today’s industrial economies.

Five pieces of compelling evidence suggest that China can pull off the transition from imported to homegrown innovation required to avoid the dreaded “middle-income trap” that ensnares most developing nations:

1. China has established 17 tech hubs that provide cultural assimilation among leading universities, venture capital investors and entrepreneurs.

2. Over the past decade, the Chinese startup culture has hit its stride. China now has more than 160 “unicorns” – private companies with valuations in excess of $1 billion each – versus about 130 unicorns in the United States. China’s unicorns span the gamut — from the fintech of internet finance and a vast e-commerce platform to online travel, cloud computing, big data management, new energy and logistics.

3. Success hinges on strategy, implementation and effective governance to catalyze the creative spark of entrepreneurs and innovators; China’s two high-profile industrial polices, Made in China 2025 and AI2030, are consistent with this objective.

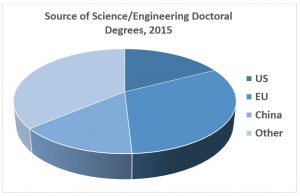

4. Chinese educational reforms now turn out more than 4.5 million scientist, technology, engineering and mathematics graduates – more than eight times that of the United States. From nanoscience and nanotechnology to quantum networking, stem-cell research and regenerative medicine, gene editing and the genetics of cancer research, and artificial intelligence, this new generation of innovators speaks volumes to China’s own “crown jewels.”

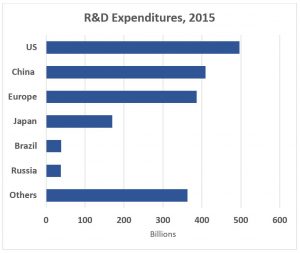

5. US National Science Foundation data put Chinese spending on overall research and development of $409 billion in 2015 (in international dollars) — nearly double that of 2010 and second only to America’s $497 billion. The NSF also reports that in 2016 China surpassed the United States as the world’s leader in academic science and engineering publications.

China may now be coming full circle — from an ancient civilization that once led the world in technology to a modern nation now focused on research, scientific development, innovation and commercialization of these activities. By fixating on intellectual property theft, cyberhacking and forced technology transfer, the US trade representative overlooks this possibility. That may well be one of America’s most egregious oversights.

Each economy needs the productivity payback from technology and innovation for its own purposes – China to avoid the middle-income trap and the United States to counter the risks of economic stagnation that might well arise from another productivity slowdown that now appears to be underway. Resolving the innovation dilemma does not imply one country defeating the other in the arena of global power.

In the end, America’s race, like that of most nations, is more with itself than with any purported foreign adversary. America’s scapegoating of China is a convenient excuse for ducking the tough issues of economic strategy that the United States has avoided for decades – namely, its saving and productivity imperatives. Both the US and China face formidable economic challenges in the years ahead. They both win if they solve their own problems, and both lose if they attack each other in a destructive and diversionary trade war.

Over time, there is a growing risk that perception becomes reality. The US body politic is in danger of convincing itself that China, a nation with a rich heritage as a leader in technological innovation, now must cheat in order to regain that edge. China, for its part, is increasingly convinced that it is being victimized by an American containment strategy aimed at its geostrategic role as well as limiting its progress on the road to innovation, sustained development and prosperity.

The longer the current US-Sino dispute persists, the deeper those convictions are likely to become ingrained on both sides of the relationship. And then, the long and tragic history of struggles between rising and ruling powers — the so-called Thucydides Trap — will become all the more relevant. Resolving the innovation dilemma is key to avoiding that dire outcome.

*Stephen S. Roach is senior fellow with Yale Jackson Institute for Global Affairs and former chairman of Morgan Stanley Asia. This article is based on a speech he gave before the AmCham China Conference in Hong Kong, September 7, 2018. He is the author of Unbalanced: The Codependency of America and China.