Israel And US Relations In Time Of Transition – Analysis

By CRS

By Jim Zanotti*

For decades, strong bilateral relations have fueled and reinforced significant U.S.-Israel cooperation in many areas, including regional security. Nonetheless, at various points throughout the relationship, U.S. and Israeli policies have diverged on some important issues. Significant differences regarding regional issues—notably Iran and the Palestinians—arose or intensified during the Obama Administration.1 Since President Donald Trump’s inauguration in January 2017, he and Israeli Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu have discussed ways “to advance and strengthen the U.S.-Israel special relationship, and security and stability in the Middle East.”2

Under President Trump, a number of developments involving the Administration, Israeli leaders, and various other actors (including Members of Congress) have affected U.S. policy. They include several controversies regarding Israeli-Palestinian issues, including the following:

- The future of U.S. policy regarding the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, a possible two-state solution, and regional Arab involvement.

- Israeli settlements in the West Bank and East Jerusalem.

- A possible move of the U.S. embassy in Israel to Jerusalem.

In early 2017, a legal probe of Prime Minister Netanyahu turned into a criminal investigation—in connection with allegations of bribery and receipt of improper gifts—that some observers speculate could threaten his term of office.3 Netanyahu has dismissed the allegations.

In the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2017 (P.L. 115-31), enacted in May 2017, Congress appropriated $75 million in Foreign Military Financing for Israel in FY2017 beyond the $3.1 billion identified for FY2017 in a U.S.-Israel memorandum of understanding (MOU) covering FY2009-FY2018. The implementation of these appropriations remain unclear, given that Prime Minister Netanyahu reportedly pledged to reimburse the U.S. government for amounts appropriated beyond the MOU amounts for FY2017 or FY2018 as part of the negotiations accompanying the September 2016 MOU that will cover FY2019-FY2028.4

U.S. Policy Options, Possible Future Negotiations, and Context

Speculation surrounds what actions the President and Congress might take on Israeli-Palestinian issues in the coming weeks and months, and how Prime Minister Netanyahu and other Israeli leaders might respond.5 President Trump has stated aspirations to help broker a final-status Israeli-Palestinian agreement as the “ultimate deal.” The President’s advisors on Israeli issues include his senior advisor Jared Kushner (who is also his son-in-law), special envoy Jason Greenblatt, and U.S. ambassador to Israel David Friedman.6

At a February 2017 White House press conference with the President, Netanyahu voiced support for an effort to involve “newfound Arab partners in the pursuit of a broader peace and peace with the Palestinians”7 that Israel had previously proposed and that the Administration is reportedly exploring. In 2016, then Secretary of State John Kerry reportedly made some initial efforts aimed at securing Israeli, Palestinian, and Arab state participation in a regional peace initiative.8 Nevertheless, it is unclear whether Arab states would be willing and able to facilitate a conflict- ending resolution between the two parties or accept normalization in their relations with Israel beforehand.

At the press conference, Netanyahu insisted on two “prerequisites for peace”: (1) Palestinian recognition of Israel as a Jewish state,9 and (2) an indefinite Israeli security presence in the Jordan Valley area of the West Bank. Given Netanyahu’s conditions, Senate Foreign Relations Committee Chairman Bob Corker inquired during the February 16 nomination hearing for Ambassador Friedman as to whether policymakers are “helping the situation by continually talking about a two-state solution when having a military presence in the West Bank ad infinitum forever by Israel is really something different than a two- state solution?”

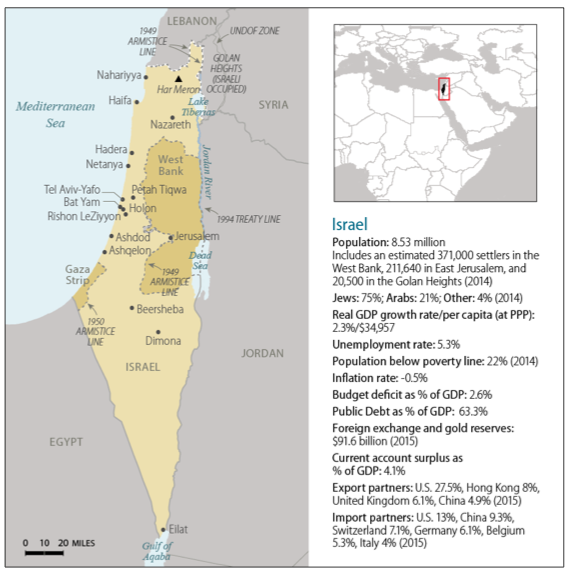

Sources: Graphic created by CRS. Map boundaries and information generated by Hannah Fischer using Department of State Boundaries (2011); Esri (2013); the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency GeoNames Database (2015); DeLorme (2014). Fact information from CIA, The World Factbook; Economist Intelligence Unit; IMF World Outlook Database; Israel Central Bureau of Statistics. All numbers are estimates and as of 2016 unless specified.

Notes: United Nations Disengagement Observer Force (UNDOF) withdrew to Israeli-controlled territory in the Golan Heights in September 2014. The West Bank is Israeli-administered with current status subject to the 1995 Israeli-Palestinian Interim Agreement; permanent status to be determined through further negotiation. The status of the Gaza Strip is a final status issue to be resolved through negotiations. Israel proclaimed Jerusalem as its capital in 1950, but the United States, like nearly all other countries, retains its embassy in Tel Aviv-Yafo. Boundary representation is not necessarily authoritative.

Since Netanyahu’s February visit, a number of developments suggest that President Trump might seek a resumption of Israeli-Palestinian negotiations. Presidential envoy Jason Greenblatt met with leading officials of both sides and of various Arab states in a March 2017 visit to the region. Palestinian Authority (PA) President Mahmoud Abbas visited the White House in early May, and signaled a willingness to return to negotiations using the 2002 Arab Peace Initiative as a starting point.10

President Trump is visiting Saudi Arabia, Israel, and the West Bank. Various U.S. figures who have prominent links to or experience with Israel are reportedly vying to influence how boldly or incrementally Trump acts in encouraging peace talks.11 A May media report indicates that Arab Gulf states may be willing to normalize some economic relations with Israel in exchange for overtures on its part. Such overtures might include limits on settlement construction or loosening restrictions on imports into the Gaza Strip.12

Other possible presidential or legislative initiatives could address these:

- U.S. aid to Israel and the Palestinians.

- U.S. policy on a two-state solution and other issues of dispute.

- U.S. contributions to and participation at the United Nations and other international bodies.13

- U.S. approaches to other regional and international actors that have roles regarding Israeli-Palestinian issues.

Some aspects of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict appear unchanged by recent diplomatic developments. Israel maintains overarching control of the security environment in Israel and the West Bank. Palestinians remain divided between a PA administration with limited self-rule in specified West Bank urban areas, led by the Fatah movement and PA President Abbas, and a de facto Hamas administration in the Gaza Strip. Both the PA and Hamas face major questions regarding future leadership.14

There has been little or no change in the gaps between Israeli and Palestinian positions on key issues of dispute since the last round of direct talks broke down in April 2014. Since 2011, Arab states that have traditionally championed the Palestinian cause have been more preoccupied with domestic and other regional concerns, and many have built or strengthened informal ties with Israel based on common views regarding Iran and its regional influence.

Questions About a Two-State Solution

Since the Israeli-Palestinian peace process began in the early 1990s, U.S. policy has largely anticipated a negotiated conflict-ending outcome that would result in two states.15 In his February White House press conference with Netanyahu, President Trump said the following in response to a question about how his vision for Middle East peace relates to those of his predecessors regarding a two-state solution:

So I’m looking at two-state and one-state, and I like the one that both parties like. I’m very happy with the one that both parties like. I can live with either one.

Palestinian diplomats and a number of international actors reacted sharply to the President’s statement.16 Subsequently, he and other U.S. officials appeared to convey that his statement was more about signaling openness to a flexible negotiating approach than a major substantive departure from past U.S. policy. Ambassador Nikki Haley, the U.S. Permanent Representative to the United Nations, was quoted as saying on February 16 that the United States still supports a two-state solution, but that the President is looking for “thinking outside the box.”17 When the President was asked in a late February interview whether he had backed away from a two-state solution, he said, “No, I like the two-state solution. But I ultimately like what [both] parties like.” He added that a two-state solution has not worked to this point.18 The larger U.S. policy context could affect various observers’ views on whether the Trump Administration’s statements signal a change in position on a two-state solution, and how influential any such change might be. In mid- May, National Security Advisor H.R. McMaster reportedly anticipated that the President would express support for Palestinian “self-determination” during his late May trip to the region.19

In a poll taken in December 2016 and released in February 2017, 54.7% of Israelis (49.9% of Israeli Jews) and 44.3% of Palestinians indicated support for a two-state solution.20 The same poll posed the following question:

Given the growing belief that the two-state solution is no longer viable, the idea of [a one-state-for-two-people] solution by which Palestinians and Jews will be citizens of the same state and enjoy equal rights is gaining some popularity. Do you support or oppose such a one-state solution?

In response to this question, 24.3% of Israelis (18.3% of Israeli Jews) and 36.2% of Palestinians indicated support.21 Many Israelis express concern that a single-state arrangement would unacceptably compromise Israel’s Jewish character.22

Settlements and Diplomatic Initiatives

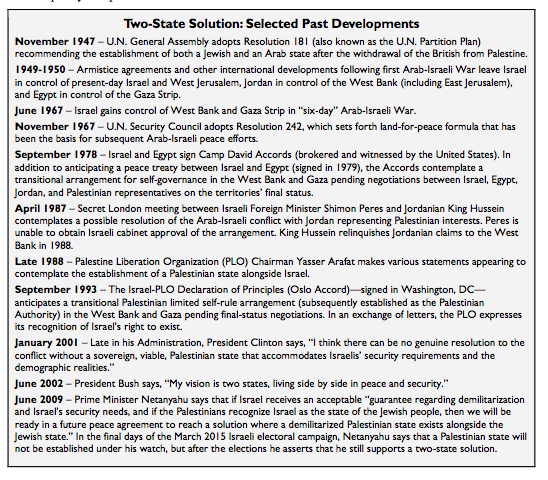

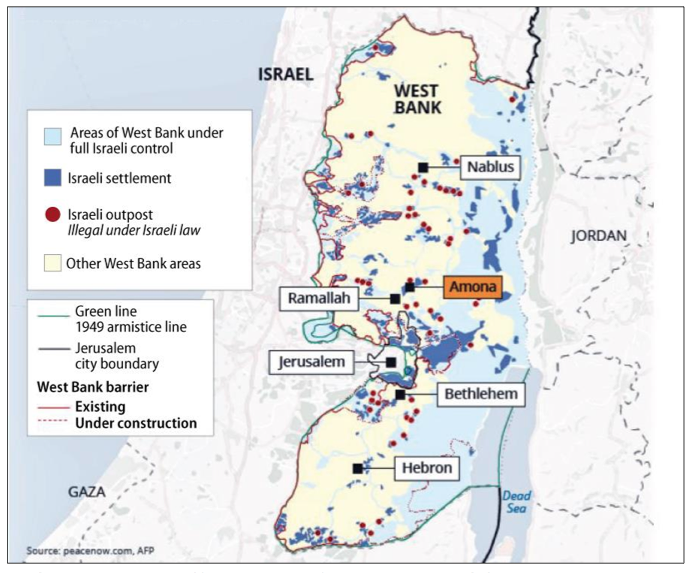

Since 1967, hundreds of thousands of Israeli civilians have settled in territory that Israel has occupied militarily since that year’s Arab-Israeli War. Approximately 385,900 Israelis lived in West Bank settlements in 2014, with about 201,200 more in East Jerusalem.23 These residential communities are located in areas that Palestinians claim as part of their envisioned future state.

Israelis who defend the settlements’ legitimacy generally cite some combination of legal, historical, strategic, nationalistic, or religious justifications, although Israeli opinion varies about different types of settlements in different locations.24

Since Israeli settlement construction began, it has attracted U.S. and international criticism. The international community generally considers Israeli construction on territory occupied in the 1967 war to be illegal.25

An April 2004 letter from President George W. Bush to then Israeli Prime Minister Ariel Sharon explicitly acknowledged that “in light of new realities on the ground, including already existing major Israeli populations (sic) centers, it is unrealistic to expect that the outcome of final status negotiations will be a full and complete return to the armistice lines of 1949.” The letter came a few months after Sharon had introduced a disengagement plan whereby Israel contemplated withdrawing from or relocating settlements that “will not be included in the territory of the State of Israel in the framework of any possible future permanent agreement.”26

The Obama Administration sought greater constraints on settlement activity than the Bush Administration.27 Although President Obama backed off his initial proposal to completely freeze settlement activity within a few months, and vetoed a draft U.N. Security Council resolution regarding the legality of settlements in February 2011, some U.S.-Israel tension on the issue continued throughout most of his presidency. In July 2016, the United States and other members of the international Quartet28 (European Union, Russia, the U.N. Secretary-General) released a report that, among other things, criticized continued settlement construction.29

In December 2016, after Trump’s election, the Obama Administration decided to abstain from (rather than veto) a U.N. Security Council resolution (Resolution 2334) that reaffirmed the illegality of settlements under international law in “Palestinian territory occupied since 1967, including East Jerusalem.” Later that month, Secretary of State John Kerry gave a speech to explain the U.S. abstention and to set forth guidance on borders, the two-state principle, Palestinian refugees, Jerusalem, security, and end-of-conflict as a possible basis for future Israeli- Palestinian negotiations.30 Resolution 2334 and Kerry’s speech both drew criticism from Trump and Netanyahu, and the House adopted H.Res. 11 condemning Resolution 2334 and the Administration’s abstaining vote.31

To date, the Trump Administration has been less critical than the Obama Administration of Israeli settlement-related announcements and construction activity. However, in February 2017, after settlement-related announcements in connection with more than 5,000 housing units and Netanyahu’s announcement of the possible construction of a new settlement as a compensatory measure for the early February evacuation of a West Bank outpost known as Amona,32 the White House press secretary released a statement with the following passage:

While we don’t believe the existence of settlements is an impediment to peace, the construction of new settlements or the expansion of existing settlements beyond their current borders may not be helpful in achieving that goal. As the President has expressed many times, he hopes to achieve peace throughout the Middle East region.33

Also, at his February 15 White House press conference with Netanyahu, President Trump told Netanyahu that he wanted to see Israel “hold back on settlements for a little bit.”

In the following weeks, the Administration and Israel’s government engaged in reported discussions in efforts to reach an understanding on settlement construction. In late March, Netanyahu’s government announced a new settlement policy that apparently sought to walk a “fine line” between maintaining good relations with the Trump Administration and placating right wing members of Netanyahu’s government who reject any freeze on building and had hoped that U.S. pressure regarding settlements would have abated more under Trump.34 The new policy left Israel room for maneuver by stating general principles aimed at keeping new construction “as close as possible” to existing built-up areas.35

Sources: Middle East Eye, 2016, with some modifications to the legend by CRS. Notes: All areas are approximate.

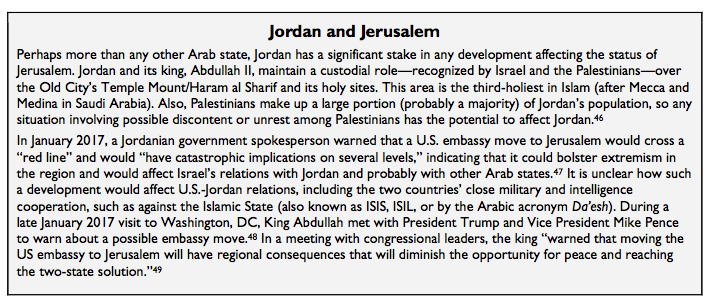

U.S. Embassy Move to Jerusalem?

Successive U.S. Administrations of both political parties since 1948 have maintained that the fate of Jerusalem is to be decided by negotiations and have discouraged the parties from taking actions that could prejudice the final outcome of those negotiations. The Palestinians envisage East Jerusalem as the capital of their future state. However, the House of Representatives passed H.Con.Res. 60 in June 1997, and the Senate passed S.Con.Res. 21 in May 1997. Both resolutions called on the Clinton Administration to affirm that Jerusalem must remain the undivided capital of Israel.

A related issue is the possible relocation of the U.S. embassy from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem. Proponents argue that Israel is the only country where a U.S. embassy is not in the capital identified by the host country, that Israel’s claim to West Jerusalem—where an embassy may be located—is unquestioned, and/or that Palestinians must be disabused of their hope for a capital in Jerusalem. Opponents say such a move would undermine prospects for Israeli-Palestinian peace and U.S. credibility with Palestinians and in the Muslim world, and could prejudge the final status of the city. The Jerusalem Embassy Act of 1995 (P.L. 104-45) provided for the embassy’s relocation by May 31, 1999, but granted the President authority, in the national security interest, to suspend limitations on State Department expenditures that would be imposed if the embassy did not open. Presidents Clinton, Bush, and Obama consistently suspended these spending limitations, and the embassy has remained in Tel Aviv. President Obama issued the most recent six-month suspension of limitations on December 1, 2016.36

Over successive Congresses, various Members have periodically introduced substantially similar versions of a Jerusalem Embassy and Recognition Act or thematically related bills or resolutions. Such legislative initiatives seek the embassy’s relocation and would remove or advocate the removal of the President’s authority to suspend the State Department expenditure limitations cited above. New versions (S. 11, H.R. 257, and H.R. 265) were introduced in January 2017.

Prospective Trump Administration Action and Potential Reaction

As a candidate, Donald Trump—like Bill Clinton and George W. Bush when they were presidential candidates—pledged to move the embassy to Jerusalem. After the election a number of Trump’s top aides reportedly stated that Trump intended to follow through on the pledge,37 and Trump himself said in response to a question on the subject shortly before his inauguration that he does not break promises.38 At his February 15 press conference with Netanyahu, the President said, “As far as the embassy moving to Jerusalem, I’d love to see that happen. We’re looking at it very, very strongly. We’re looking at it with great care.”

Some media outlets anticipate that the President will renew the Jerusalem Embassy Act suspension of limitations on June 1 while he and his Administration continue deliberations on a possible move in the larger context of their aspirations to assist in an Israeli-Palestinian peace initiative.39 Some U.S. officials have reportedly advised the President not to move the embassy.40 On May 14, Netanyahu’s office released a statement saying, “Moving the American embassy to Jerusalem would not harm the peace process. On the contrary, it would advance it by correcting an historical injustice and by shattering the Palestinian fantasy that Jerusalem is not the capital of Israel.”41

Some observers claim that moving the U.S. embassy could lead to a number of negative consequences. Before leaving office, former Secretary Kerry predicted that such a move could lead to an “explosion” in the region, and as the presidential transition was underway, Israeli authorities reportedly contemplated scenarios involving possible violent responses by Palestinians.42 In December, the PLO’s chief negotiator threatened to reverse the recognition the PLO has accorded Israel to date.43 One opponent of the move argued that it would be “in direct violation” of the 1993 Declaration of Principles (also known as the Oslo Accord).44 Some observers appear to base their stated concerns about an embassy move not on an imminent expectation of security problems or dramatic diplomatic backlash, but on the possibility that a move could undermine promising opportunities for Israel to work with Arab states.45

However, proponents of a move downplay such concerns. One proponent asserted that widespread de facto acceptance of West Jerusalem as part of Israel means that relocating the embassy to Jerusalem would not prejudice the U.S. stance on the city’s ultimate status, including that of the Old City and the holy sites.50 A former senior U.S. official on Israeli-Palestinian issues wrote in January 2017 that coupling an embassy move with a larger diplomatic initiative regarding Jerusalem’s status could possibly aid the peace process, under certain circumstances.51

Even before President Trump’s inauguration, media sources and other observers speculated about how the incoming Administration might logistically handle an embassy move. They discussed the use of sites owned or leased by the U.S. government as possible venues for an embassy in Jerusalem.52 They also raised the possibility of Trump designating the existing U.S. Consulate General in Jerusalem (which currently only deals with Palestinians in the West Bank, East Jerusalem, and Gaza) as an embassy or an embassy annex.53 Another way the Administration could claim to follow through on Trump’s campaign pledge could be for Ambassador Friedman to conduct official business in Jerusalem, where he owns a residence.54 A May 2017 article indicated, however, that Friedman is initially expected to live and work out of Tel Aviv while serving as ambassador.55

Domestic Israeli Developments

A number of controversial domestic developments have taken place in 2017. Contention surrounding these issues may be greater given the possibility of early elections (legally, elections are required by 2019) if the governing coalition splits over Israeli-Palestinian negotiations, the criminal investigation into Netanyahu’s conduct, or some other issue.

- In February, the Knesset passed the Regulation Law. The law is expected by many observers to be overturned by Israel’s Supreme Court.56 Pending judicial action, the law authorizes the Israeli government to expropriate private Palestinian property in order to provide a basis for the legality (under Israeli law) of perhaps more than half of the approximately 100 settlement outposts.57

- Also in February, Sergeant Elor Azaria, a former military medic, was sentenced by an Israeli military court to 18 months in prison for manslaughter for shooting and killing a Palestinian (in March 2016) who had attacked an Israeli soldier minutes earlier but had been disarmed, was wounded, and no longer appeared to present a threat. The case, verdict, and sentencing generated enormous controversy domestically and internationally.58

- In March, the Knesset passed the Amendment Law, which prohibits foreigners from entering Israel if they have publicly committed to boycott Israel or areas it controls.59 In light of evidence that some individuals have had their entry into Israel delayed or denied under the law, some of the law’s opponents warn of negative consequences to Israel if it keeps out avowed supporters of Israel who oppose settlements.60

- In early May, the Knesset Ministerial Committee on Legislation placed the Nationality Bill on the legislative agenda. If passed, the bill would define Israel as the national homeland of the Jewish people and establish Hebrew as the only official language (downgrading Arabic to a special status). Although its direct effect would be largely symbolic, some observers are concerned that the bill might further undermine the place of Arabs in Israeli society.61

- In mid-May, Israel’s new public broadcasting corporation began operations after contention between Netanyahu and Finance Minister Moshe Kahlon over how to manage the transition from the previous broadcasting authority had threatened the governing coalition. The previous week, the Knesset had voted to establish a news department independent of the new public broadcaster, raising concerns about the overall viability of public broadcasting under the new system, as well as about possible government efforts to control the content of news broadcasts.62

If elections take place this year, Netanyahu could face challenges from his right or left on the political spectrum by figures including Education Minister Naftali Bennett, Defense Minister Avigdor Lieberman, Yair Lapid (a former finance minister), Gideon Saar (a former interior and education minister), and Moshe Ya’alon (the previous defense minister).

About the author:

*Jim Zanotti, Specialist in Middle Eastern Affairs

Source:

This article has been edited from the original content that was published by CRS (Congressional Research Service) as Israel: Background and U.S. Relations in Brief (PDF).

Notes:

1 See, e.g., Jeffrey Goldberg, “The Obama Doctrine,” The Atlantic, April 2016; Jason M. Breslow, “Dennis Ross: Obama, Netanyahu Have a ‘Backdrop of Distrust,’” PBS Frontline, January 6, 2016; Sarah Moughty, “Michael Oren: Inside Obama-Netanyahu’s Relationship,” PBS Frontline, January 6, 2016.

2 White House Office of the Press Secretary, “Readout of the President’s Call with Prime Minister Netanyahu of Israel,” January 22, 2017.

3 Oren Liebermann, “Netanyahu’s criminal investigation drags on into the summer,” CNN, May 9, 2017.

4 “U.S.-Israel Deal held up over Dispute with Lindsey Graham,” Washington Post, September 11, 2016.

5 See, e.g., Uri Savir, “Trump’s Mideast plan starts taking shape,” Al-Monitor Israel Pulse, April 30, 2017; Barak Ravid and Amir Tibon, “U.S. Ambassador Advises Israeli Officials: Trump’s Serious About Peace, Work With Him,” Ha’aretz, May 12, 2017.

6 Friedman’s nomination and Senate confirmation (which took place via a 52-46 vote) attracted attention because of his past statements and financial efforts in support of controversial Israeli settlements in the West Bank, and his sharp criticism of the Obama Administration, some Members of Congress, and some American Jews. See, e.g., “David Friedman, Trump’s Israel envoy pick, reportedly behind newly approved settler homes,” Jewish Telegraphic Agency (JTA), February 9, 2017; Judy Maltz, “David Friedman Raised Millions for Radical West Bank Jewish Settlers,” Ha’aretz, December 16, 2016; Matthew Rosenberg, “Trump Chooses Hard-Liner as Ambassador to Israel,” New York Times, December 15, 2016; At Friedman’s February 16, 2017, nomination hearing before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, he apologized for and expressed regret regarding many of the critiques he previously directed at specific people.

7 White House Office of the Press Secretary, Remarks by President Trump and Prime Minister Netanyahu of Israel in Joint Press Conference, February 15, 2017.

8 Barak Ravid, “Exclusive-Kerry Offered Netanyahu Regional Peace Plan in Secret 2016 Summit With al-Sissi, King Abdullah,” Ha’aretz, February 19, 2017.

9 Although the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) explicitly recognized Israel’s right to exist in 1993, PLO leaders have been reluctant to publicly accept that Israel is the “nation-state of the Jewish people” because of concerns that doing so could contribute to negative effects for the Arab citizens who make up approximately 20% of Israel’s population, as well as undermine the claims of Palestinian refugees to a “right of return” to their original or ancestral homes in present-day Israel.

10 White House Office of the Press Secretary, Remarks by President Trump and President Abbas of the Palestinian Authority in Joint Statement, May 3, 2017. The Arab Peace Initiative offers a comprehensive Arab peace with Israel if Israel were to withdraw fully from the territories it occupied in 1967, agree to the establishment of a Palestinian state with a capital in East Jerusalem, and provide for the “[a]chievement of a just solution to the Palestinian Refugee problem in accordance with UN General Assembly Resolution 194.” The initiative was proposed by Saudi Arabia, adopted by the 22-member Arab League (which includes the PLO), and later accepted by the 56-member Organization of the Islamic Conference (now the Organization of Islamic Cooperation) at its 2005 Mecca summit. The text of the initiative is available at http://al-bab.com/documents-section/arab-peace-initiative-2002.

11 See, e.g., Amir Tibon, “These Are the Voices Whispering in Trump’s Ear About Israel and How to Make the ‘Ultimate Deal,’” Ha’aretz, May 15, 2017; Mark Landler and Maggie Haberman, “Mixed Messages From Trump Worry Pro-Israel Hard-Liners,” New York Times, May 6, 2017.

12 Jay Solomon and Gordon Lubold, “Arab States Make an Offer to Israel—Gulf states set to take steps toward better relations in return for move by Netanyahu,” Wall Street Journal, May 16, 2017.

13 All 100 Senators joined in a letter dated April 27, 2017, to U.N. Secretary-General Antόnio Guterres urging him to “pursue a comprehensive effort to improve the U.N.’s treatment of Israel.” Section 7048(c) of the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2017 (P.L. 115-31), prohibits funding in support of the U.N. Human Rights Council unless the Secretary of State determines “that participation in the Council is important to the national interest of the United States and that the Council is taking significant steps to remove Israel as a permanent agenda item.”

14 See CRS In Focus IF10644, The Palestinians: Overview and Key Issues for U.S. Policy, by Jim Zanotti. After more than a decade as Hamas’ international face, outgoing political bureau chief Khaled Meshaal publicly presented a new political document in early May 2017. The document—summarizing positions that Meshaal and other Hamas political leaders had informally articulated in previous years, but that may not have full backing within the movement’s political or military wings—accepts the possibility of a Palestinian state in an area smaller than what Britain administered until 1948 (comprising present-day Israel, the West Bank, and Gaza Strip), states that Hamas opposes Zionism rather than Judaism, and does not reference Hamas’s Muslim Brotherhood roots. But the document voices Hamas’s continued commitment to armed “resistance” and does not recognize Israel. “Hamas says it accepts ’67 borders, but doesn’t recognize Israel,” CNN, May 3, 2017. Within a week after the document’s release, Hamas’s former leader in Gaza, Ismail Haniyeh, was named as Meshaal’s replacement. Prime Minister Netanyahu and other Israeli officials rejected the notion that the document reflected a change in Hamas’s worldview or position.

15 Peter Baker, “U.S. Won’t Press a Two-State Path to Mideast Peace,” New York Times, February 16, 2017.

16 Ian Fisher, “Palestinians Dismayed at U.S. Shift on Policy,” New York Times, February 16, 2017; “Egypt and Jordan: Don’t give up on two-state solution,” JTA, February 21, 2017; Kambiz Foroohar, “Trump Team Sows Confusion on Two-State Solution for Mideast,” Bloomberg, February 16, 2017; Julian Borger, “US ambassador to UN contradicts Trump’s position on two-state solution,” Guardian, February 16, 2017.

17 Foroohar, op. cit.

18 Steve Holland, “Exclusive: Trump likes two-state solution, but says he will leave it up to Israelis, Palestinians,” Reuters, February 23, 2017.

19 Matt Spetalnick, “Trump to back Palestinian ‘self-determination’ on Mideast trip: aide,” Reuters, May 12, 2017.

20 Poll taken December 8-10, 2016, by the Tami Steinmetz Center for Peace Research, Tel Aviv University, and the Palestinian Center for Policy and Survey Research, with a margin of error of 3%. Results available at http://www.pcpsr.org/sites/default/files/Table%20of%20Findings_English%20Joint%20Poll%20Dec%202016_12Feb2 017.pdf. According to the poll, support among Israelis and Palestinians for specific parameters linked with a two-state solution fluctuates depending on the parameters.

21 Ibid.

22 See, e.g., Holland, op. cit.

23 CIA World Factbook estimates as of 2014 (which are the most recent as of May 17, 2017).

24 For more information on the history of the settlements and their impact on Israeli society, see Naval Postgraduate School, Religious Zionism and Israeli Settlement Policy, 2014; Charles Selengut, Our Promised Land: Faith and Militant Zionism in Israeli Settlements, Rowman & Littlefield, 2015; Gershom Gorenberg, The Accidental Empire: Israel and the Birth of the Settlements, 1967-1977, New York: Times Books, 2006.

25 The most-cited international law pertaining to Israeli settlements is the Fourth Geneva Convention, Part III, Section III, Article 49 Relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War, August 12, 1949, which states in its last sentence, “The Occupying Power shall not deport or transfer parts of its own civilian population into the territory it occupies.” Israel counters that the West Bank does not fall under the international law definition of “occupied territory,” but is rather “disputed territory” because the previous occupying power (Jordan) did not have an internationally recognized claim to it. Israel claims that, given the demise of the Ottoman Empire at the end of World War I and the end of the British Mandate in 1948, no international actor has a superior legal claim.

26 Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Address by PM Ariel Sharon at the Fourth Herzliya Conference, December 18, 2003.

27 U.S. and Israeli leaders publicly differed on whether Obama’s expectations of Israel contradicted statements that the George W. Bush Administration had made. Some Israeli officials and former Bush Administration officials said that the United States and Israel had reached an unwritten understanding that “Israel could add homes in settlements it expected to keep [once a final resolution with the Palestinians was reached], as long as the construction was dictated by market demand, not subsidies.” Glenn Kessler and Howard Schneider, “U.S. Presses Israel to End Expansion,” Washington Post, May 24, 2009. This article quotes former Bush Administration deputy national security advisor Elliott Abrams as saying that the United States and Israel reached “something of an understanding.” The accounts of former Bush Administration officials diverge in their characterization of U.S.-Israel talks on the subject, but the Obama Administration insisted that if understandings ever existed, it was not bound by them. Ethan Bronner, “Israelis Say Bush Agreed to West Bank Growth,” New York Times, June 3, 2009.

28 The Quartet formed in 2002 as an effort by the members to pool their efforts in mitigating conflict and promoting the peace process.

29 The report text is available at http://www.un.org/News/dh/infocus/middle_east/Report-of-the-Middle-East- Quartet.pdf. The report also lamented terrorist attacks against civilians and Palestinian incitement to violence.

30 State Department transcript of Kerry’s remarks, Washington, DC, December 28, 2016, available at https://2009- 2017.state.gov/secretary/remarks/2016/12/266119.htm.

31 H.Res. 11 was adopted on January 5, 2017, by a 340-80 vote (with four voting “present”).

32 In late March, Israeli officials confirmed the establishment of a new settlement, reportedly the first in two decades. 33 White House Office of the Press Secretary, Statement by the Press Secretary, February 2, 2017.

34 For example, Naftali Bennett (a Netanyahu coalition partner and political challenger, with extensive settler support) supports an initiative that would reportedly see the settlement of Ma’ale Adumim (approximate population: 40,000) just east of Jerusalem “annexed as a first step toward applying Israeli law and ending military rule” over the 60% of the West Bank that is under Israeli control.

35 Isabel Kershner, “Israel Says It Will Rein In ‘Footprint’ of Settlements,” New York Times, April 1, 2017. Israeli officials generally seek to ensure Israel’s future sovereignty in “settlement blocs”—areas that they anticipate will be within the boundaries of Israel if the issue of borders is eventually finalized with the Palestinians via negotiations. However, construction-related announcements have continued in 2017 in areas that are either outside blocs identified by Israel or whose inclusion within Israel’s borders could harm the contiguity of a future Palestinian state and its access to water or other resources. Isabel Kershner, “A Bolder Israel Plans to Expand Its Settlements,” New York Times, January 25, 2017.

36 https://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2016/12/01/presidential-determination-suspension-limitations-under- jerusalem.

37 Daniel Estrin, “Trump Favors Moving U.S. Embassy to Jerusalem, Despite Backlash Fears,” NPR, November 15, 2016.

38 Ian Fisher, “Netanyahu Says U.S. Should Move Its Embassy,” New York Times, January 30, 2017.

39 Josh Lederman, “Tillerson: Trump weighs embassy move impact on Mideast peace,” Associated Press, May 14,

2017; Ravid and Tibon, op. cit.

40 Jeremy Diamond and Elise Labott, “Top US officials warn Trump against moving US embassy to Jerusalem,” CNN, May 15, 2017.

41 Israeli Prime Minister’s Office, Statement by PM Netanyahu’s Office Regarding US Secretary of State Tillerson’s Remarks, May 14, 2017. Netanyahu’s office has released information to counter media reports that he privately urged Trump not to move the embassy during his February White House visit. Barak Ravid, “PM’s Office Publishes Records of Trump Meeting to Prove Netanyahu Backed Moving U.S. Embassy to Jerusalem,” Ha’aretz, May 15, 2017. Some observers suggest that an embassy move is not a high priority for Netanyahu in comparison with various regional security threats, but that domestic political realities are compelling him to address the subject. Mark Landler, “Before a Visit to Israel, Small Issues Prove Thorniest,” New York Times, May 16, 2017.

42 Barak Ravid, “Netanyahu Briefed on Scenarios of Violence Should Trump Move Embassy to Jerusalem,” haaretz.com, January 21, 2017.

43 Eli Lake, “Israel Needs Its Arab Friends More Than U.S. Embassy Move,” Bloomberg, December 21, 2016.

44 Danny Seidemann, “Moving the U.S. Embassy in Israel to Jerusalem: A Hard Look at the Arguments and Implications,” Insiders’ Jerusalem, January 3, 2017. See Article V, Section 3 of the Oslo Accord, which states that permanent status negotiations “shall cover remaining issues, including: Jerusalem, refugees, settlements, security arrangements, borders, relations and cooperation with other neighbors, and other issues of common interest.” http://www.mfa.gov.il/MFA/ForeignPolicy/Peace/Guide/Pages/Declaration%20of%20Principles.aspx. Israel and the PLO were the two parties to the Oslo Accord. The United States and Russia both witnessed the document.

45 See, e.g., Lake, op. cit.

46 Josh Lederman, “Trump courts Jordan’s king amid embassy, refugee concerns,” Associated Press, January 30, 2017. 47 Jack Moore, “Jordan Tells Trump: Moving U.S. Embassy to Jerusalem a ‘Red Line,’” Newsweek, January 6, 2017. 48 Kershner, op. cit.; Lederman, op. cit.

49 Jordanian Royal Hashemite Court website, King meets members, committees of US Congress, January 31, 2017.

50 Amiad Cohen, “Please, America, Move Your Embassy to Jerusalem,” nytimes.com, December 27, 2016.

51 Martin Indyk, “The Jerusalem-first option,” New York Times, January 6, 2017.

52 Raphael Ahren, “Jerusalem of Trump: Where the president-elect might put the US embassy,” Times of Israel, December 13, 2016; Tamar Pileggi, “Trump’s team already exploring logistics of moving embassy to Jerusalem — report,” Times of Israel, December 12, 2016.

53 Efraim Cohen, “How Trump Could Make Quick Move to Jerusalem for U.S. Israel Embassy,” New York Sun, December 13, 2016.

54 See, e.g., Julie Hirschfeld Davis, “Trump Speaks With Netanyahu, Seeking to Thaw U.S. Relations,” New York Times, January 23, 2017.

55 Lederman, op. cit.

56 Ian Fisher, “Israel Passes Provocative Legislation to Retroactively Legalize Settlements,” New York Times, February 7, 2017.

57 Joe Dyke, “Clashes as Israel evicts wildcat settlers,” Agence France Presse, February 1, 2017.

58 “Israeli soldier gets 18 months for fatal shooting of Palestinian attacker,” Associated Press, February 21, 2017.

59 Ruth Levush, “Israel: Prevention of Entry of Foreign Nationals Promoting Boycott of Israel,” Global Legal Monitor, Law Library of Congress, March 17, 2017.

60 Joshua Mitnick, “Law in Israel bans boycott backers,” Los Angeles Times, March 7, 2017.

61 See, e.g., Mazal Mualem, “Does Israel really need the Nationality Law?” Al-Monitor Israel Pulse, May 9, 2017.

62 Jonah Mandel, “Israel broadcaster enters new era after tearful farewell,” Agence France Presse, May 15, 2017; Marissa Newman, “Knesset okays changes to new public broadcaster, ending years-long fight,” Times of Israel, May 11, 2017; Isabel Kershner, “‘Undignified’ End for Respected Israeli News Shows,” New York Times, May 11, 2017.