Japan’s Expanding Military Role: A Stabilising Factor – Analysis

By Observer Research Foundation

By Rajeswari Pillai Rajagopalan*

Amid loud confrontations, the Japanese Parliament on September 19 passed two security laws that will continue the inching effort to normalise Japan, marking another shift from the post-World War II pacifism. The bills were passed with 148 Diet members in favour and 90 against them. The laws will now go to the Supreme Court, where it could get overturned.

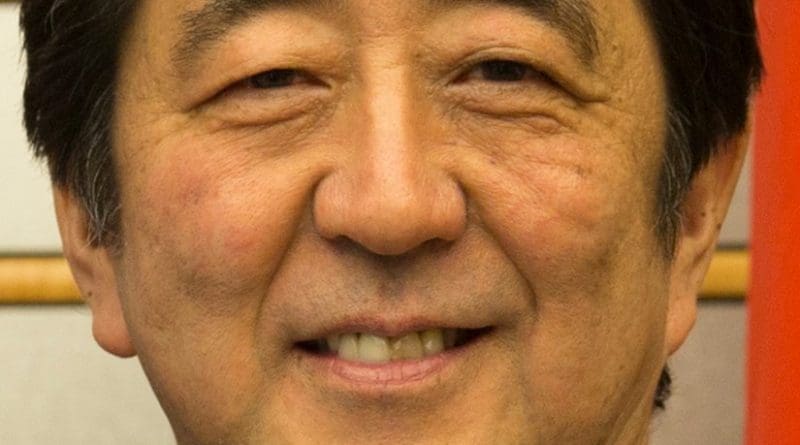

In the face of a near impossible task of amending the Japanese Constitution, Prime Minister Shinzo Abe took the relatively easier path of introducing the two security bills. Even though the laws have been passed, there is significant opposition from lawmakers, scholars and the public in general. A recent poll conducted by Asahi Shimbun newspaper said that 54 percent of the nearly 2000 people surveyed for the poll were against the bills and only 29 percent supported them. There were thousands of Japanese citizens sitting outside the Parliament protesting against the legislation and calling the introduction of these new measures unconstitutional. Abe, however, maintained that “the changes were a normalisation of Japan’s military policy, which has been restricted to self-defence and aid missions by a pacifist constitution imposed by the US after World War II.” Abe and his supports said the laws are important also in the context of regional security, with increasing threats from a “belligerent China and unstable North Korea.”

The two laws cleared by the Diet will remove several legal restrictions on Japanese security policy, including one to exercise collective self-defence option. This would mean that even if Japan is not under direct attack, Tokyo can support and defend its ally (the United States). Abe rationalised this by saying that the US-Japan alliance “would be critically damaged if Tokyo refused to defend the US during operations aimed at protecting Japan.” The new laws will also facilitate Japanese Self Defence Forces (JSDF) participating in UN-mandated military operations. This will replace the current situation where temporary laws are enacted every time Japan decides to participate in a mission. While this appears to be simply a measure to ease the process through a one-time legislation, there is fear that Japan could be drawn into a range of military operations and conflicts that Tokyo may not directly be interested in.

The new legislation has clearly irked Japan’s neighbours. Predictably, both China and South Korea have criticised the move saying they threaten regional peace. China’s defence ministry stated that the new laws “aroused grave concern among its own citizens, Asian neighbouring countries and the international security.” The South Korean foreign ministry released a statement saying “in deciding and implementing defense and security policy down the road, Japan will have do so with transparency and in the direction of contributing to regional peace and stability, while maintaining the spirit of the pacifist constitution.”

Pyongyang too has reacted to the introduction of new bills, arguing that the new moves will be a “grave threat to peace and stability in Asia and the rest of the world,” and that North Korea will have to respond by strengthening “the war deterrence to cope with the dangerous moves for aggression against it.” Given the nature of history in Asia among these powers, the reactions are along the expected lines. In another reaction along expected lines, the US welcomed the new legislation. Calling the move a historic one, the US State Department spokesperson said, “We welcome Japan’s ongoing efforts to strengthen the alliance (with the United States) and play a more active role in regional and international security activities.”

The debate around Article 9 and Japan assuming a proactive military role has been going on for a while, and gained greater traction in the last couple of years since Abe came into office. While Abe’s rightwing background became a particularly important factor in pushing this, the US’ relative decline, made worse by Obama’s seeming disinterest in traditional allies or commitments, has played a role as well. This has meant that Japan has had to undertake steps including altering of its security laws and diplomatic maneuvering and outreach to old and new partners in Asia and beyond.

The US has also been increasingly calling on Japan to shoulder more responsibility in the US-Japan security alliance. The credibility of the US as a security guarantor has been an issue, especially under the Obama Administration. The persisting doubts over the US commitment to Japan’s position on the Senkaku Islands also make the case for Japan to become more muscular. Obama’s interest in a closer relationship with China is seen as putting the Japanese security concerns at risk. How the North Korean problem will be dealt with by Washington is another important factor. Seeing the Obama Administration strike a nuclear deal with Iran at the cost of the US’ long-standing allies such as Israel and Saudi Arabia has not been particularly reassuring to Japan. There are also practical concerns because of which Tokyo needs to do more in the security realm. Japanese territory is only minutes away from North Korean missiles making it difficult for Tokyo to take a sanguine view of the threat it faces.

Japan’s new security legislation is a long-awaited move, something that is to be welcomed in the regional context. In the face of an aggressive China and a belligerent North Korea, Japan has been compelled to shed its unnaturally and purely pacifist posture and develop capabilities that are in tune with the new realities. The legislation is also symbolic, indicating the Japanese willingness to take responsibility for maintaining its own security. A militarily capable Japan not restricted by its constitution could therefore potentially become a stabilizing factor in the regional context.

*Dr. Rajeswari Pillai Rajagopalan is a Senior Fellow at Observer Research Foundation, Delhi